Staples Theory, Oil, and Indigenous Alternative Development in the Northwest Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Leonard Tilley

SIR LEONARD TILLEY JAMES HA NNAY TORONTO MORANG CO L IMITE D 1911 CONTENTS EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER ELECTED T0 THE LEGISLAT' RE CHAPTER III THE PROHIBITORY LI' ' OR LAW 29 CHAPTER VI THE MOVEMENT FOR MARITIME ' NION CONTENTS DEFEAT OF CONFEDERATION CHAPTER I' TILLEY AGAIN IN POWER CHAPTER ' THE BRITISH NORTH AMERICA ACT CHA PTER ' I THE FIRST PARLIAMENT OF CANADA CHAPTER ' II FINANCE MINISTER AND GO VERNOR INDE' CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER HE po lit ic al c aree r of Samuel Leonard Tilley did not begin until the year t hat bro ught the work of L emuel Allan Wilmot as a legislator to a we e elect ed e bers t he close . Both r m m of House of 1 850 t he l ea Assembly in , but in fol owing y r Wil elev t ed t o t he benc h t h t t he mot was a , so a province lost his services as a political refo rmer just as a new t o re t man, who was destined win as g a a reputation t he . as himself, was stepping on stage Samuel l at t he . Leonard Til ey was born Gagetown , on St 8th 1 8 1 8 i -five John River, on May , , just th rty years after the landing of his royalist grandfather at St. - l t . e John He passed away seventy eight years a r, ull t he f of years and honours , having won highest prizes that it was in the power of his native province t o bestow. -

RS24 S1- S43 Introduction

The General Assembly of New Brunswick: Its History and Records The Beginnings The History The Records in Context The History of the Sessional Records (RS24) The Organization of the Sessional Records (RS24) A Note on Spellings Notes on Place Names List of Lieutenant-Governors and Administrators Guide to Sessional Records (RS24) on Microfilm 1 The Beginnings: On August 18, 1784, two months after the new province of New Brunswick was established, Governor Thomas Carleton was instructed by Royal Commission from King George III to summon and call a General Assembly. The steps taken by Governor Carleton in calling this assembly are detailed in his letter of October 25, 1785, to Lord Stanley in the Colonial Office at London: "My Lord, I have the honor to inform your Lordship that having completed such arrangements as appeared to be previously requested, I directed writs to issue on the 15th instant for convening a General Assembly to meet on the first Tuesday in January next. In this first election it has been thought advisable to admit all males of full age who have been inhabitants of the province for no less than three months to the privilege of voting, as otherwise many industrious and meritorious settlers, who are improving the lands allotted to them but have not yet received the King's Grant, must have been excluded. … The House of Representatives will consist of 26 members, who are chosen by their respective counties, no Boroughs or cities being allowed a distinct Representation. The county of St. John is to send six members, Westmorland, Charlotte, and York four members each, Kings, Queens, Sunbury and Northumberland, each two members. -

JOHN A. MACDONALD the Indispensable Politician

JOHN A. MACDONALD The Indispensable Politician by Alastair C.F. Gillespie With a Foreword by the Hon. Peter MacKay Board of Directors CHAIR Brian Flemming Rob Wildeboer International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor, Halifax Executive Chairman, Martinrea International Inc., Robert Fulford Vaughan Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, columnist VICE CHAIR with the National Post, Ottawa Jacquelyn Thayer Scott Wayne Gudbranson Past President and Professor, CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa Cape Breton University, Sydney Stanley Hartt MANAGING DIRECTOR Counsel, Norton Rose Fulbright LLP, Toronto Brian Lee Crowley, Ottawa Calvin Helin SECRETARY Aboriginal author and entrepreneur, Vancouver Lincoln Caylor Partner, Bennett Jones LLP, Toronto Peter John Nicholson Inaugural President, Council of Canadian Academies, TREASURER Annapolis Royal Martin MacKinnon CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson Former federal cabinet minister, Counsel at Fasken DIRECTORS Martineau, Toronto Pierre Casgrain Director and Corporate Secretary of Casgrain Maurice B. Tobin & Company Limited, Montreal The Tobin Foundation, Washington DC Erin Chutter Executive Chair, Global Energy Metals Corporation, Vancouver Research Advisory Board Laura Jones Janet Ajzenstat, Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Professor Emeritus of Politics, McMaster University of Independent Business, Vancouver Brian Ferguson, Vaughn MacLellan Professor, Health Care Economics, University of Guelph DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, Toronto Jack Granatstein, Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Advisory Council Patrick James, Dornsife Dean’s Professor, University of Southern John Beck California President and CEO, Aecon Enterprises Inc., Toronto Rainer Knopff, Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Professor Emeritus of Politics, University of Calgary President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Corp., Calgary Larry Martin, Jim Dinning Prinicipal, Dr. -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 2nd SESSION . 37th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 140 . NUMBER 41 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, March 19, 2003 ^ THE HONOURABLE DAN HAYS SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates and Publications: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Communication Canada ± Canadian Government Publishing, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S9. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 956 THE SENATE Wednesday, March 19, 2003 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Acting Speaker in the Chair. As of March 11, 2003, 89 countries had joined the International Criminal Court. These 89 members are expected to select a Prayers. prosecutor at the end of April of this year. Once this step has been taken, the court will be able to investigate and prosecute [Translation] individuals accused of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes in those countries that are party to the Rome Statute, which created the court. The ICC is to complement existing ROYAL ASSENT national legal systems and will only prosecute individuals in cases where national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or The Hon. the Acting Speaker informed the Senate that the prosecute such crimes. following communication had been received: RIDEAU HALL The International Criminal Court represents an important development for international law in combating impunity. It is an March 19, 2003 honour for Canada to see one of our own chosen to be the first president of an institution that has the potential of playing a key Mr. Speaker, role in bringing to justice those found guilty of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes. -

Joe Cherwinski Fonds

MG 429 - Joe Cherwinski fonds Dates: 1914-2006 (inclusive); 1965-2000 (predominant). Extent: 5.08 m of textual records, 127 photographs, 11 negatives, 133 slides, 1 reel-to reel; 2 DVD; 8 reels of microfilm; 82 fiche; 1 disc; 23 posters; memorabilia; and library; plus oversize. Biography: Walter Joseph Carl Cherwinski was born on 26 April 1942 in Yorkton, Saskatchewan. He earned both his BA (1964) and MA (1966) from the University of Saskatchewan, and his PhD (1972) from the University of Alberta. He worked as research assistant to Eugene Forsey, and as a sessional lecturer at the University of Regina and the University of Alberta, prior to accepting a permanent position in the history department at Memorial University, Newfoundland. His research related primarily to prairie agricultural labour. He is author of numerous articles relating to labour issues, migrant workers on the prairies, and prairie history. Scope and content: This fonds contains the drafts, notes, and reference materials relating to Cherwinski’s research on prairie labour and history. Arrangement: It has been organized into 9 series: 1. Personal 2. Letters to Albert: The Main Family Correspondence from Saskatchewan, 1908-1925. 3. Prairie Farm Labour 4. Research – Various 5. Saskatchewan Organized Labour 6. Schwinghamer General Store 7. Winter on the Prairies: 1906-1907 8. Posters 9. Library Restrictions: Files marked as restricted must be vetted by archivist prior to use. Donated by WJC Cherwinski to the University of Saskatchewan Archives in 2012. Original finding aid by Patrick Hayes. Edited by Amy Putnam, 2018. Box 1 SERIES 1: PERSONAL British Columbia Today! – 1928. -

Famous New Brunswickers A

FAMOUS NEW BRUNSWICKERS A - C James H. Ganong co-founder ganong bros. chocolate Joseph M. Augustine native leader, historian Charles Gorman speed skater Julia Catherine Beckwith author Shawn Graham former premier Richard Bedford Bennett politician, Phyllis Grant artist philanthropist Julia Catherine Hart author Andrew Blair politician Richard Hatfield politician Winnifred Blair first miss canada Sir John Douglas Hazen politician Miller Brittain artist Jack Humphrey artist Edith Butler singer, songwriter John Peters Humphrey jurist, human Dalton Camp journalist, political rights advocate strategist I - L William "Bliss" Carman poet Kenneth Cohn Irving industrialist Hermenegilde Chiasson poet, playwright George Edwin King jurist, politician Nathan Cummings founder Pierre-Amand Landry lawyer, jurist consolidated foods (sara lee) Andrew Bonar Law statesman, british D - H prime minister Samuel "Sam" De Grasse actor Arthur LeBlanc violinist, composer Gordon "Gordie" Drillon hockey player Romeo LeBlanc politician, statesman Yvon Durelle boxing champion M Sarah Emma Edmonds union army spy Antonine Maillet author, playwright Muriel McQueen Fergusson first Anna Malenfant opera singer, woman speaker of the canadian senate composer, teacher Gilbert Finn politician Louis B. Mayer producer, co-founder Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (born in Russia) Gilbert Ganong co-founder ganong bros. chocolate Harrison McCain co-founder mccain Louis Robichaud politician foods Daniel "Dan" Ross author Wallace McCain co-founder mccain foods -

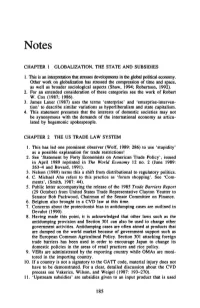

CHAPTER 1 GLOBALIZATION, the STATE and SUBSIDIES 1. This Is

Notes CHAPTER 1 GLOBALIZATION, THE STATE AND SUBSIDIES 1. This is an interpretation that stresses developments in the global political economy. Other work on globalization has stressed the compression of time and space, as well as broader sociological aspects (Shaw, 1994; Robertson, 1992). 2. For an extended consideration of these categories see the work of Robert W. Cox (1987; 1986). 3. James Laxer (1987) uses the terms 'enterprise' and 'enterprise-interven tion' to describe similar variations as hyperliberalism and state capitalism. 4. This statement presumes that the interests of domestic societies may not be synonymous with the demands of the international economy as articu lated by hegemonic spokespeople. CHAPTER 2 THE US TRADE LAW SYSTEM 1. This has led one prominent observer (Wolf, 1989: 286) to use 'stupidity' as a possible explanation for trade restrictions! 2. See 'Statement by Forty Economists on American Trade Policy', issued in April 1989 reprinted in The World Economy 12 no. 2 (June 1989: 263-4 and Bovard, 1991). 3. Nelson (1989) terms this a shift from distributional to regulatory politics. 4. C. Michael Aho refers to this practice as 'forum shopping'. See 'Com ments', (Smith, 1987: 44). 5. Public letter accompanying the release of the 1985 Trade Barriers Report (29 October) from United States Trade Representative Clayton Yeutter to Senator Bob Packwood, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance. 6. Belgium also brought in a CVD law at this time. 7. Concerns about the protectionist bias in antidumping cases are outlined in Devalut (1990). 8. Having made this point, it is acknowledged that other laws such as the antidumping provision and Section 301 can also be used to change other government activities. -

This Week in New Brunswick History

This Week in New Brunswick History In Fredericton, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Howard Douglas officially opens Kings January 1, 1829 College (University of New Brunswick), and the Old Arts building (Sir Howard Douglas Hall) – Canada’s oldest university building. The first Baptist seminary in New Brunswick is opened on York Street in January 1, 1836 Fredericton, with the Rev. Frederick W. Miles appointed Principal. Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) becomes responsible for all lines formerly January 1, 1912 operated by the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) - according to a 999 year lease arrangement. January 1, 1952 The town of Dieppe is incorporated. January 1, 1958 The city of Campbellton and town of Shippagan become incorporated January 1, 1966 The city of Bathurst and town of Tracadie become incorporated. Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of MGM Studios (Hollywood, California), January 2, 1904 leaves his family home in Saint John, destined for Boston (Massachusetts). New Brunswick is officially divided into eight counties of Saint John, Westmorland, Charlotte, Northumberland, King’s, Queen’s, York and Sunbury. January 3, 1786 Within each county a Shire Town is designated, and civil parishes are also established. The first meeting of the New Brunswick Legislature is held at the Mallard House January 3, 1786 on King Street in Saint John. The historic opening marks the official business of developing the new province of New Brunswick. Lévite Thériault is elected to the House of Assembly representing Victoria January 3, 1868 County. In 1871 he is appointed a Minister without Portfolio in the administration of the Honourable George L. Hatheway. -

Why History Matters

SSpringpring 220101 5 + WWhyhy HHistoryistory MMattersatters 12. TThehe HHistoryistory ooff JJewishewish StudentStudent LLifeife aatt UUCC 18. UUCC QQuadrangleuadrangle PPastast aandnd ffutureuture 24 . uc.utoronto.ca/alumni CONTENTS SPRING 2015 fFeatures eauc.uttoronto.cau/alumni res KEYNOTE 08. Principal's Message CLASS NOTES 12. 18. 38. FOCUS REPORT News from Alumni Why Bother With History? The History of Jewish BY FRANCESCO GALASSI Student Life at UC BY FRANKLIN BIALYSTOK NOTA BENE 42. Campus News 24. CAMPUS Quiet, Green, and Orderly: The History of the UC Quadrangle BY JANE WOLFF 32. CAMPAIGN UPDATE 04 — UC ALUMNI MAGAZINE Leading by Example BY SHELDON GORDON CONTENTS SPRING 2015 MASTHEAD Departments uc.utoronto.ca/alumni Volume 40, No. 2 EDITOR Yvonne Palkowski (BA 2004 UC) SPECIAL THANKS Donald Ainslie Alana Clarke (BA 2008 UC) Naomi Handley Michael Henry Lori MacIntyre COVER IMAGE University College, Junior Common Room, c. 1965 Courtesy UC Archives ART DIRECTION & DESIGN www.typotherapy.com PRINTING Flash Reproductions CORRESPONDENCE AND UNDELIVERABLE COPIES TO: University College Advancement Office 15 King’s College Circle 10. Toronto, ON, M5S 3H7 University College Alumni Magazine 01. is published twice a year by the University College Advancement departments Office and is circulated to 26,000 alumni and friends of University College, University of Toronto. IMAGE 01. 06. 45. To update your address or David Secter on set CONTRIBUTORS DONATIONS Our Team University College unsubscribe send an email to IMAGE CREDIT Donors [email protected] Courtesy Gwendolyn 07. Pictures 48. with your name and address or BRIEFLY call (416) 978-2139 or toll-free Editor’s Note DONATIONS The University College 1-800-463-6048. -

Summary Perspectives Link Opens in New Window

Summary Perspective The Province of Canada: Canada West John A. Macdonald and his allies mobilized massive support for Confederation. George Brown and his supporters also saw more advantages than drawbacks, although they had some reservations. Representation The province would finally get more representatives to match its growing population. It would therefore carry more political weight within the new Confederation than in the Province of Canada. Prosperity Confederation would create new markets, make the railway companies more profitable and help people enter the territory to settle land in the West. Security Confederation would allow better military protection against the Americans and others. Since the advantages were obvious, 54 of the 62 members of the Legislative Assembly from Canada West voted in favour of ratifying the Confederation initiative. Summary Perspective Province of Canada: Canada East George-Étienne Cartier’s party, the Parti bleu, enthusiastically supported the Confederation initiative. Antoine-Aimé Dorion’s Parti rouge was, however, opposed. Autonomy and Survival The province would maintain control of its language, religion, education system and civil law. The rights of French Canadians would therefore be safe from the English. However, some people were worried about the scope of the federal government’s power. They thought that the French would be outnumbered by the English, and that the religion most Francophones practiced might be threatened by the Protestant religion favoured by most English. Security Confederation would allow better military protection against the Americans and others. Some were scared, however, that the union might make people from other countries angry by provoking them into a fight. If all of the colonies were getting together, other countries might see a threat, and want to deal with it. -

FEBRUARY 2003 Graham Fraser

THE NDP LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE—RE-CONNECTING THE LEFT TO THE MIDDLE In the run-up to the NDP leadership vote on January 25, party activists faced a difficult choice between two apparent front runners, the well known face of NDP House Leader Bill Blaikie of Manitoba, and Toronto city councillor Jack Layton, an interesting new face with national credentials as president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. While Blaikie represents the party’s deep roots in the West and the co-operative movement, Layton represents the possibility of taking the NDP back into the cities and union towns of southern Ontario, where it was strong during the era of Ed Broadbent from 1975-1988, a highwater mark in NDP history. Toronto Star columnist Graham Fraser, widely acclaimed for his books on Canadian politics, offers this situational update on a party confronting an agonizing choice. Graham Fraser En prévision du scrutin à la direction du Nouveau Parti Démocratique du 25 janvier, les militants font face à un choix difficile entre les deux candidats les plus en vue : le Manitobain Bill Blaikie, leader du NPD à la Chambre des communes, et Jack Layton, conseiller municipal de la ville de Toronto et un temps président de la Fédération canadienne des municipalités. Un premier visage très connu, donc, et un second qui gagne à l’être. Si Blaikie représente le profond enracinement du parti dans l’Ouest du pays et le mouvement coopératif, Layton incarne pour sa part l’espoir de lui rendre la popularité dont il jouissait dans les grands centres et les villes ouvrières du sud de l’Ontario, où le NPD a connu une période historiquement fastueuse sous le règne d’Ed Broadbent, de 1975 à 1988. -

Kari Levitt and the Long Detour of Canadian Political Economy1 May 28, 2004 by Paul Kellogg

Kari Levitt and the Long Detour of Canadian Political Economy1 May 28, 2004 By Paul Kellogg Paper presented as part of the panel, “Canadian Nationalism and Industrial Policy,” 2004 meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba Draft only / Not for quotation Comments to [email protected] Introduction: the return of a classic..............................................................................1 Future imperfect..........................................................................................................2 Chart 1: U.S. control of assets and revenue in the Canadian state, 1965-2000 ..........3 Chart 2: Composition of Canadian Export Trade, 1971-2004...................................8 Chart 3: Composition of Canadian Export Trade, excluding automobile and truck exports, 1971-2004..................................................................................................9 Chart 4: Finished manufactured export as percent of GDP, Canada and the U.S., 1998-2002 .............................................................................................................10 The central role of FDI ..............................................................................................11 Chart 5: Net Foreign Direct Investment, Canada, 1926-2002 (billions of 2003 dollars) ..................................................................................................................13 Chart 6: Net Foreign Direct Investment, and Net International Investment