The Role of Creative Methods in Re-Defining The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Between the Lines Alumni in the Media 2 You Must Remember This

Aston University Alumni Magazine Issue 15 Spring 2005 LA Story Reading between the lines Alumni in the media 2 You must remember this... You must remember this... A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, Princess Leia and R2-D2 welcomed the first arrivals at the May Ball. Contents 3 You must 16 remember this... 5 11 19 29 Contents Special thanks go to everyone who contributed to this Features issue of Apex. Apex is published twice a year for alumni Reading between the lines 4 of Aston University. Letters, photographs and news M for safety 7 are very welcome but we reserve the right to edit any contributions. Please address all correspondence to Alumni in the media 8 the Alumni Relations Offi cer. The opinions expressed in Report on the AGM of Convocation 10 Apex are those of the contributors and do not necessarily LA story 14 refl ect those of the Alumni Relations Offi ce or Aston University. Regulars Apex is also available via the website in html or pdf You must remember this 2 formats, but please contact us if you experience any Profile on… 6 diffi culties accessing the publication. Where are they now? 24 How to contact the Alumni Relations Office: Reunions 29 www.aston.ac.uk/alumni AGA 30 [email protected] In-touch 31 T +44 (0)121 204 3000 Gifts 32 F +44 (0)121 359 4664 Alumni Relations Office News Aston University, Aston Triangle Applications to Aston on the increase 5 Birmingham, B4 7ET, UK Careers services for Aston graduates 6 Designed by Linney Design The Net works 9 Printed by Linney Print Long service awards 11 Photo credits: Ed Moss, pages 5, 16, 17 18, 19, 22, Topping-off ceremony 11 and 23; Tony Flanagan page 17; John Hipkiss pages International news 12 6, 10 and 28; Martin Levenson pages 9 and 28. -

Research at Keele

Keele University An Employer of Choice INVISIBLE THREADS FORM THE STRONGEST BONDS INTRODUCTION FROM THE VICE-CHANCELLOR hank you for your interest in one of our vacancies. We hope you will explore the variety of opportunities open to you both on a personal and professional level at Keele University Tthrough this guide and also our web site. Keele University is one of the ‘hidden gems’ in the UK’s higher education landscape. Keele is a research led institution with outstanding teaching and student satisfaction. We have also significantly increased the number of international students on campus to c. 17% of our total taught on-campus student population. Our ambitions for the future are clear. Keele offers a ‘premium’ brand experience for staff and students alike. We cannot claim that our experience is unique, but it is distinctive, from the scholarly community resident on campus – we have over 3,200 students living on campus, along with over 170 of the staff and their families – to the innovative Distinctive Keele Curriculum (DKC) which combines curriculum, co-curriculum and extra-curricular activities into a unique ‘offer’ that can lead to accreditation by the Institute of Leadership and Management (ILM). We have a strong research culture too, with a good research profile in all our academic areas, and world-leading research in a number of focused fields. These range from inter alia Primary Health Care to Astrophysics, Insect- borne disease in the Tropics, Sustainability and Green Technology, Ageing, Music, History and English literature. We continually attract high calibre applicants to all our posts across the University and pride ourselves on the rigour of the selection process. -

Student Protection Plan: Nuala Devlin – Dean of Student Services Student Protection Plan for the Period 2020-2021 1

Provider’s name: Staffordshire University Provider’s UKPRN: 10006299 Legal address: Staffordshire University, College Road, Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire, ST4 2DE Contact point for enquiries about this student protection plan: Nuala Devlin – Dean of Student Services Student protection plan for the period 2020-2021 1. An assessment of the range of risks to the continuation of study for your students, how those risks may differ based on your students’ needs, characteristics and circumstances, and the likelihood that those risks will crystallise Staffordshire University is a modern, relevant and vocationally inspired institution, working with industry to support regional economic growth and provide opportunities for a diverse student body. We have built on our strong heritage and mission and, as “The Connected University”, we continue to deliver innovative and applied learning, develop talented people and connect our communities to opportunities that will support them to improve economically, societally and culturally. The University is organised into five Schools: o Staffordshire Business School (SBS) o Digital, Technologies and Arts (DTA) o Health and Social Care (HSC) o Law, Policing and Forensics (LPF) o Life Sciences and Education (LSE) The School subject combinations reflect employer needs for graduates with broader skills, knowledge and an agility. Underpinned by a connected curriculum approach, the University is working in partnership with students to be active, digital, global citizens. The University has a diverse student population with a percentage of local and regional students. We have a relatively small number of students from out-side of the UK and are therefore not over exposed to the withdrawal from the European union or changes in Home Office immigration regulations. -

British Early Career Mathematicians' Colloquium 2020 Abstract Booklet

British Early Career Mathematicians' Colloquium 2020 Abstract Booklet 14th - 15th July 2020 Plenary Speakers Pure Mathematics: Applied Mathematics: Jonathan Hickman Adam Townsend University of Edinburgh Imperial College London Liana Yepremyan Gabriella Mosca The London School of Economics University of Z¨urich and Political Science Jaroslav Fowkes Anitha Thillaisundaram University of Oxford University of Lincoln Contact: Website: http://web.mat.bham.ac.uk/BYMC/BECMC20/ E-mail: [email protected] Organising Committee: Constantin Bilz, Alexander Brune, Matthew Clowe, Joseph Hyde, Amarja Kathapurkar (Chair), Cara Neal, Euan Smithers. With special thanks to the University of Birmingham, MAGIC and Olivia Renshaw. Tuesday 14th July 2020 9.30-9.50 Welcome session On convergence of Fourier integrals Microscale to macroscale in suspension mechanics 10.00-10.50 Jonathan Hickman (Plenary Speaker) Adam Townsend (Plenary Speaker) 10.55-11.30 Group networking session Strong components of random digraphs from the The evolution of a three dimensional microbubble in non- Blocks of finite groups of tame type 11.35-12.00 configuration model: the barely subcritical regime Newtonian fluid Norman MacGregor Matthew Coulson Eoin O'Brien Large trees in tournaments Donovan's conjecture and the classification of blocks Order from disorder: chaos, turbulence and recurrent flow 12.10-12.35 Alistair Benford Cesare Giulio Ardito Edward Redfern Lunch break MorphoMecanX: mixing (plant) biology with physics, Ryser's conjecture and more 14.00-14.50 mathematics -

Research in Real Life How Universities Have Contributed in the Fight Against Covid 19

Research in real life How Universities have contributed in the fight against Covid 19. Aims - To understand the contribution students, academics and staff in Universities have made in the battle against Covid 19. - To understand the different types of research being conducted. - To understand why Universities are important in this pandemic. #WeAreTogether #WeAreTogether is a campaign that highlights the incredible work Universities are doing in the fight against Coronavirus. Universities across the UK (and the world) are carrying out unprecedented work to fight Covid 19, whether that be via staff, research or manufacturing equipment. This movement is like no other documented and so the #WeAreTogether campaign showcases how everyone in society is benefiting from our Universities. #WeAreTogether Tweets Oxford University heads up research on Covid 19 Where would we be without our Universities? Oxford University is leading the way in pioneering research against the virus. Here are a few examples of their research. University contribution Universities including staff, academics and students have been hugely beneficial in the fight against Coronavirus. 1) Research, vaccines & testing What would the battle have looked like without our Universities? Considering the significant impact they have had so far? 2) Resources & people power It’s highly likely that a report will be released in years to come that investigates the true input 3) Supporting through the crisis (students & the of our Universities. community To get an idea as to the types of offerings the Higher Horizons partner Universities have contributed, we have broken down just a fraction of their support into 3 categories: - Research, vaccines & testing Keele University Researchers have volunteered to help the UK’s effort to increase coronavirus testing. -

Medicine Mbchb Single Honours

Course Information Document: Undergraduate For students starting in Academic Year 2020/21 1. Course Summary Names of programme and Medicine MBChB Honours Degree award title(s) Award type Single Honours Mode of study Full-time Framework of Higher Education Qualification Level 6 (FHEQ) level of final award Normal length of the 5 years programme Maximum period of The normal length as specified above plus 3 years registration Location of study Hospital - Medical Keele Campus Accreditation (if applicable) This programme is accredited by the General Medical Council. For further details see the section on accreditation. Regulator Office for Students (OfS); General Medical Council UK/EU students: Fee for 2020/21 is £9,250* International students: Fee for 2020/21 is £35,000** Bursary information: Home (England and Wales) and EU students are eligible for an NHS bursary towards their fees in their 5th year of study not counting repeated years. For Scotland and Northern Ireland, students Tuition Fees should check directly with their relevant authority. More information on eligibility can be found on the NHS Bursaries website: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/nhs-bursary-students International students are not eligible for the NHS Bursary. Placements: We will confirm the clinical placement supplement for international students commencing their studies in 2020-21 as soon as possible but must await further guidance from Health Education England. How this information might change: Please read the important information at http://www.keele.ac.uk/student-agreement/. This explains how and why we may need to make changes to the information provided in this document and to help you understand how we will communicate with you if this happens. -

Through the Distinctive Keele Curriculum

1. University Vision What is this about? Why have a masterplan? Keele University’s Vision Keele University is currently producing a new The purpose of the masterplan is to define a high level The six aims of the University’s Strategic Plan are campus masterplan. The masterplan will set a vision strategy for the University estate that supports: summarised below. and framework for how the campus estate should • The University’s vision for a single integrated develop over the next 10 years. campus comprising both the University campus and Keele Science and Innovation Park; This exhibition presents the masterplan as it currently • The University’s Strategic Plan, guiding stands, to inform the local campus and neighbouring investment in the University estate over the short communities, and to gain any feedback on the to medium term. proposals and policies. • The emerging Keele Neighbourhood Plan and AIMS AND OBJECTIVES AIMS AND OBJECTIVES AIMS AND OBJECTIVES Joint Stoke / Newcastle Local Plans. AIM 1 AIM 2 AIM 3 To continue building Through the Distinctive To deliver international Keele as a broad-based Keele Curriculum excellence and impact in research-led University provide outstanding focused areas of research of about 13000 students discipline-based education recognised internationally and a unique portfolio of for excellence in education, personal development research and enterprise opportunities in the context of a sector-leading student experience AIMS AND OBJECTIVES AIMS AND OBJECTIVES AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 10 12 14 AIM 4 AIM 5 AIM 6 To contribute positively To promote environmental To transform how we work to the society, economy, sustainability in all that we do to ensure the University’s culture, health and development is sustainable well-being of the and delivers world-leading communities we serve teaching and research 16 18 20 Masterplan Principles this will dilute Keele University’s distinctive enhance its residential provision to provide between The masterplan has also been informed by the curriculum including research-led teaching. -

Understanding and Maximising Leadership in Pre-Registration Healthcare Curricula

Understanding and Maximising Leadership in Pre-registration Healthcare Curricula September 2015 Working in partnership with: Authors and Key Contributors Principal Investigator Louise Jones, Strategic Director for Health and Well-being, University of Worcester Lead Commissioner Adam Turner, Leadership OD and Talent Programme Lead, Health Education West Midlands Laura Torney Research Assistant, Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester Sarah Baxter Director Health and Social Care Unit, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University (Carole) Dawn Johnson Head of Continuing Professional Development, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Keele University Anne O’Brien Director of Undergraduate programmes and Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, School of Health and Rehabilitation, Keele University Dr Patricia Owen Director of Undergraduate programmes and Senior Lecturer in Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Keele University Dr Alan Taylor Senior Lecturer, Leadership, Management and Service Development, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University. Robert Dudley Associate Head of Institute (Professional Programmes) and Head of Academic Unit of Nursing, Midwifery, and Paramedic Science, Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester 2 Contents Authors and Key Contributors ................................................................................................................ 2 Contents ................................................................................................................................................. -

Developing Undergraduate Programme Specifications

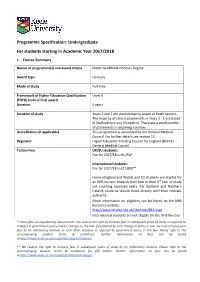

Programme Specification: Undergraduate For students starting in Academic Year 2017/2018 1. Course Summary Names of programme(s) and award title(s) Medicine MBChB Honours Degree Award type Honours Mode of study Full time Framework of Higher Education Qualification Level 6 (FHEQ) level of final award Duration 5 years Location of study Years 1 and 2 are predominantly based at Keele campus. The majority of clinical placements in Years 3 - 5 are based in Staffordshire and Shropshire. There are a small number of placements in adjoining counties. Accreditation (if applicable) This programme is accredited by the General Medical Council. For further details see section 12. Regulator Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) General Medical Council Tuition Fees UK/EU students: Fee for 2017/18 is £9,250* International students: Fee for 2017/18 is £27,800** Home (England and Wales) and EU students are eligible for an NHS bursary towards their fees in their 5th year of study not counting repeated years. For Scotland and Northern Ireland, students should check directly with their relevant authority. More information on eligibility can be found on the NHS Bursaries website: http://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/Students/816.aspx International students are not eligible for the NHS Bursary. * These fees are regulated by Government. We reserve the right to increase fees in subsequent years of study in response to changes in government policy and/or changes to the law. If permitted by such change in policy or law, we may increase your fees by an inflationary amount or such other measure as required by government policy or the law. -

Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering

Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering Version 2.3 EBSE Technical Report EBSE-2007-01 Software Engineering Group School of Computer Science and Mathematics Keele University Keele, Staffs ST5 5BG, UK and Department of Computer Science University of Durham Durham, UK 9 July, 2007 © Kitchenham, 2007 0. Document Control Section 0.1 Contents 0. Document Control Section......................................................................................i 0.1 Contents ..........................................................................................................i 0.2 Document Version Control.......................................................................... iii 0.3 Document development team ........................................................................v 0.4 Executive Summary......................................................................................vi 0.5 Glossary ........................................................................................................vi 1. Introduction............................................................................................................1 1.1 Source Material used in the Construction of the Guidelines .........................1 1.2 The Guideline Construction Process..............................................................2 1.3 The Structure of the Guidelines .....................................................................2 1.4 How to Use the Guidelines ............................................................................2 -

Uk University Salaries 2015-16

IN THE MONEY?: UK UNIVERSITY SALARIES 2015-16 Academics Professional and support staff Managers, directors Professor Other senior academic Other Academic total and senior officials Professional, technical and clerical Manual staff Non-academic total Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All Female Male All University of Aberdeen £73,143 £80,757 £79,156 .. £114,461 £102,490 £41,830 £45,690 £44,018 £45,217 £54,483 £50,824 £58,403 £59,310 £58,896 £30,683 £35,583 £32,423 £20,122 £22,932 £22,384 £30,991 £32,832 £31,801 Abertay University .. £63,717 £63,764 .. £66,617 £66,491 £40,197 £42,258 £41,419 £42,562 £47,158 £45,441 .. £75,041 £68,896 £28,985 £31,879 £30,029 .. £23,379 £22,900 £30,084 £32,874 £31,387 Aberystwyth University £67,667 £72,679 £71,989 .. .. .. £41,757 £43,249 £42,689 £43,994 £49,324 £47,525 £46,820 £49,492 £48,423 £28,502 £30,153 £29,224 £18,075 £18,782 £18,675 £29,070 £27,845 £28,400 Anglia Ruskin University £66,238 £65,406 £65,723 £77,006 £96,030 £87,383 £43,323 £43,394 £43,357 £46,384 £49,223 £47,771 £55,661 £66,201 £60,839 £32,075 £35,007 £33,163 £22,979 £24,293 £23,787 £32,859 £35,786 £34,063 University of the Arts London £71,562 £68,132 £70,071 £78,617 £95,898 £86,768 £49,686 £48,278 £48,892 £54,437 £53,243 £53,782 £64,498 £65,740 £65,170 £35,436 £38,509 £36,596 £26,479 £26,416 £26,425 £36,752 £38,560 £37,532 Arts University Bournemouth . -

Living at Your Home from Home 2 | Living at Keele Welcome to Keele | 3

KeeleLiving at Your home from home 2 | Living at Keele Welcome to Keele | 3 Keele welcomes you to our beautiful campus that gives you 600 acres of space to study, relax, thrive and explore and Welcome make your home from home. Everything is just a short walk away Top 10 from the central campus, from study areas IN ENGLAND FOR OVERALL STUDENT to accommodation, to cafés and open SATISFACTION spaces, you’re never far away from what to Keele NSS 2021 (BROAD-BASED you need at Keele. PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES) 4 | Living at Keele Accommodation at Keele | 5 Accommodation at Keele There’s a variety of accommodation at Keele, with the aim of suiting a range of student lifestyle needs and budgets. Open days and offer Our guarantee Students with a holder days We prioritise all new September disability or health We hold campus open days and entry full-time students and condition international students for offer holder days to give you the We offer a guarantee of on campus accommodation. We opportunity to tour the campus, campus accommodation to offer guaranteed accommodation including the halls of residence. all students with long term on campus for September entry Tours are guided by our Student medical conditions or disabilities undergraduate applicants who Ambassadors, to enable you who choose Keele as their make Keele their firm choice, and to ask any questions you may first choice and apply by the who apply for accommodation have. This will also give you the deadline. We want you to reach by the deadline date. opportunity to view bedrooms, your potential and will do all communal spaces and facilities.