A Paradigm Shift in Global Surgery Training: Rwanda’S Human Resources for Health (Hrh) Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation Matters: Pioneering Innovation Today for Health Impact

Innovation Pioneering innovation today for health matters im Pact tomorrow Amie Batson Seth Berkley Balram Bhargava Agnes Binagwaho Børge Brende Steve Davis Haitham El-noush Anthony Fauci Craig Friderichs Tore Godal Glenda Gray Felix Olale Allan Pamba Rajiv Shah Peter Singer Gavin Yamey With a message from UN Secretary- General Ban Ki-moon Smart phone- readable and standardized QR codes to track medicines? A field-based test for water safety that quantifies risk? Simulation programs to help health workers manage emergency obstetric and neonatal care? A highly efficacious HIV vaccine? Diagnostic and screening tools for malaria and TB, tailored specifically for low-resource settings? m essage from the Un secretary-general Since the launch of the Every Woman Every Child movement in 2010, leaders from government, civil society, multilateral organizations, and the private sector have worked hand-in-hand to improve health and save lives around the world. By Ban Ki-moon Building on earlier work, our collective efforts have achieved much progress: Secretary-General Maternal and child deaths have been cut by almost half since 1990. Remarkable of the United Nations technological advances in recent years, such as low-cost vaccines, new drugs, diagnostic tools, and innovative health policies, have driven this unprecedented reduction in maternal and child mortality. The innovative Every Woman Every Child partnership model has proven to be a game-changer for women’s and children’s health, demonstrating the immense value of bringing all relevant actors to the table. Many other innovations, including more efficient distribution networks, the use of mobile technologies to reach women in rural areas, and local vaccine production, have also played an important role in generating new progress for women’s and children’s health. -

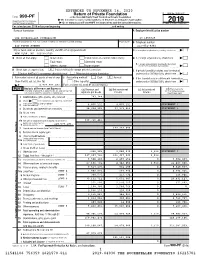

990-PF Or Section 4947(A)(1) Trust Treated As Private Foundation | Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

EXTENDED TO NOVEMBER 16, 2020 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation | Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury 2019 Internal Revenue Service | Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2019 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION 13-1659629 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 420 FIFTH AVENUE 212-852-8361 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ~ | NEW YORK, NY 10018-2702 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~ | Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ~~~~ | X H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~ | X I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~ | | $ 4,929,907,452. -

Rwanda One Health Steering Committee

Republic of Rwanda MINISTRY OF HEALTH ONE HEALTH STRATEGIC PLAN (2014-2018) “No single individual, discipline, sector or ministry can pre-empt and solve complex “health” problems” Rwanda One Health Country Steering Committee. Rubavu, 7th February 2013 Foreword Today, the world is facing numerous challenges that require multi sector and global solutions. One of these challenges is the occurrence and spread of infectious diseases that emerge or re-emerge and have an effect on humans, ecosystem interfaces, wild and domesticated animals. This is mainly attributed to several factors including the exponential growth in human and livestock populations, rapid urbanization, rapidly changing farming systems, closer interaction between livestock and wildlife, forest encroachment, changes in ecosystems, the globalization of trade of animals and their products.. Worldwide, lessons learnt from the prevention and control of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 highlighted the need to shift to an integrative and holistic approach such as the One Health approach. With increased global human activity on the environment and the global movement of people, increased trading of animals and their products, Rwanda is susceptible to the occurrence and spread of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases that can have a disastrous on the socio-economic growth. To overcome this challenge, the Ministry of Health in collaboration with other stakeholders developed the Rwanda One Health strategic plan. The One Health Strategic plan reflects shared commitments to enhance collaboration between environmental, animal (wildlife and domestic) and human health, and strengthening the new one health workforce capacity through higher institutions of learning. The strategy also outlines interventions to be undertaken by government institutions and other partners to enhance existing structures and pool together additional resources to prevent and control zoonotic diseases and other events of public health importance. -

Home Truths Facing the Facts on Children, AIDS, and Poverty

Embargoed Until 10 February 2009; 12h00 GMT Home Truths Facing the Facts on Children, AIDS, and Poverty Final Report of the Joint Learning Initiative on Children and HIV/AIDS The Joint Learning Initiative on Children and hiv/aids (jlica) gratefully acknowledges the support and engagement of its Founding Partner organizations: Association François-Xavier Bagnoud — fxb International; the Bernard van Leer Foundation; fxb Center for Health and Human Rights, Harvard University; the Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University; the Human Sciences Research Council; and the United Nations Children’s Fund (unicef). jlica also acknowledges the generous financial support of its major donors: Irish Aid, the United Kingdom Department for International Development (dfid), the Government of the Netherlands, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Joint United Nations Programme on hiv/aids (unaids). © Joint Learning Initiative on Children and hiv/aids (jlica) 2009. This report summarizes the findings and recommendations of the Joint Learning Initiative on Children and hiv/aids (jlica). The contents of the report emerge from the work of jlica’s four Learning Groups and the contributions of all Learning Group members. Responsibility for all aspects of the report rests with jlica. The views and recommendations expressed are not necessarily those of jlica’s Founding Partner organizations and supporters. The principal writers of this report were Alec Irwin, Alayne Adams, and Anne Winter. Editorial guidance was provided by members of the jlica Steering Committee, including: Bilge Bassani, Peter Bell, Agnès Binagwaho, Lincoln Chen, Madhu Deshmukh, Chris Desmond, Alex de Waal, Geoff Foster, Stuart Gillespie, Jim Kim, Peter Laugharn, Masuma Mamdani, Lydia Mungherera, Kavitha Nallathambi, Linda Richter, and Lorraine Sherr. -

Curriculum Vitae Autobiographical Article: from A

LAWRENCE O. GOSTIN Curriculum Vitae Phone: +1 202 662-9373 Georgetown University Law Center Email: [email protected] 600 New Jersey Ave., NW Washington, DC 20001 WEBSITES INTERNET RESOURCES Autobiographical Article: From a Civil Libertarian to a Sanitarian, 34 J. LAW & SOCIETY 594-616 (Dec 2007) The Lancet Profile: Lawrence Gostin: Legal Activist in the Cause of Global Health, 386 THE LANCET 2133 (Nov 28, 2015). Faculty Profile O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law: Global Health & Human Rights Database, in partnership with the WHO and Lawyers’ Collective of India. O’Neill Institute, Prof. Gostin’s Health Tips Georgetown Law Faculty Profile Public Health Post Profile SCHOLARLY PRODUCTIVITY AND IMPACT A systematic empirical analysis of legal scholarship, independent researchers ranked Prof. Gostin 1st in the nation in productivity among all law professors, and 11th in impact and influence. In 2017, researchers ranked Professor Gostin 1st in the nation in citations for health law. Prof. Gostin is also ranked first among health law professors on Google Scholar and on West Law (2018). He is in the top 10% worldwide for downloads on SSRN. MAJOR GLOBAL HEALTH CAMPAIGNS THE JOINT ACTION AND LEARNING INITIATIVE: TOWARDS A FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON GLOBAL HEALTH In 2008, at the founding of the O’Neill Institute, Prof. Gostin proposed a Framework Convention on Global Health founded on the right to health, published in the Georgetown Law Journal. A decade later, in 2018, civil society organizations from every region of the world launched the Framework Convention on Global Health Alliance. The groundwork for the Alliance had been laid by the Joint Action and Learning Initiative on National and Global Responsibilities for Health and the Platform for an FCGH. -

Women Leaders in Global Health Conference 2019 Proceeding Report

KIGALI The University of Global Health Equity presents the; CONVENTION CENTRE RWANDA WOMEN LEADERS IN GLOBAL HEALTH CONFERENCE 2019 PROCEEDING REPORT In affiliation with conference participants, delegates, sponsors and academic partners 9-10TH NOVEMBER HOSTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF GLOBAL HEALTH EQUITY 9-10TH INTRODUCTION NOVEMBER INTRODUCTION The University of Global Health Equity (UGHE) partnered with Women Leaders in Global Health Initiative, now renamed WomenLift Health, which is an initiative of Stanford University to address challenges to better health outcomes, and increase investment in health and education through promoting women’s representation in leadership globally. Through this initiative, two consecutive conferences were undertaken in 2017 (hosted by Stanford University) and 2018 (hosted by London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine). The WLGH conference series rotates every year in other regions. Building on the experiences from these Conferences, the 2019 Women Leaders in Global Health Conference (WLGH19) was hosted in Rwanda, Kigali Convention Center across November 9- 10, 2019, by the University of Global Health Equity (UGHE), to continue the global agenda for better gender equity in health research in academia and in clinical fields. The organization of this conference required identification and recruitment of relevant speakers, panelists and mentors to share leadership experiences, lessons, and best practices. As with previous WLGH Conferences, UGHE organized an international conference committee, a scientific committee, and a national conference committee to facilitate the preparation and implementation of the Conference. Organizers of the event included an operational team at UGHE, and external advisory groups below. a) International Conference Committee: This group was composed of highly esteemed professionals in Global Health who volunteered their time for activities including liaising with key contacts and developing the conference program. -

Commitment to Gender Equality Through Gender Sensitive Financing

Commentary BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006747 on 27 July 2021. Downloaded from Commitment to gender equality through gender sensitive financing 1 1 1,2 Agnes Binagwaho , Kedest Mathewos , Alice Uwase Bayingana , Tsion Yohannes1 To cite: Binagwaho A, INTRODUCTION Summary box Mathewos K, Bayingana AU, Since the 1970s, countries across the globe et al. Commitment to and various institutions have declared their ► Despite various international commitments to gen- gender equality through 1 gender sensitive financing. commitment to gender equality. The United der equality since the 1970s, significant gender BMJ Global Health Nations (UN) held the First World Confer- gaps persist across various dimensions of human 2021;6:e006747. doi:10.1136/ ence on Women in Mexico City in 1975, development. bmjgh-2021-006747 bringing together representatives from 133 ► Countries and private foundations have shown limit- countries.2 The conference that cemented ed progress in allocating funds towards programmes Received 27 June 2021 the world’s commitment to gender equality and initiatives aimed at achieving gender equality. Accepted 29 June 2021 was the UN Fourth World Conference on ► The meager funds currently allocated towards achieving gender equality often fail to fund local Women in 1995 which brought together organisations and are targeted towards addressing 17 000 official participants and 30 000 activists 3 immediate issues rather than creating sustainable to Beijing, China. Participants devised the change. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action ► The under- representation of women in global health which outlines commitments to 12 areas of leadership prevents a systemic approach to ad- concern and serves as a crucial guiding docu- dressing gender inequality. -

Improving the World's Health Through the Post-2015 Development Agenda

http://ijhpm.com Int J Health Policy Manag 2015, 4(4), 203–205 doi 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.46 Perspective Improving the world’s health through the post-2015 development agenda: perspectives from Rwanda Agnes Binagwaho1,2,3*, Kirstin W Scott4 Abstract Article History: The world has made a great deal of progress through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to Received: 11 December 2014 improve the health and well-being of people around the globe, but there remains a long way to go. Here Accepted: 27 February 2015 we provide reflections on Rwanda’s experience in working to meet the health-related targets of the MDGs. ePublished: 1 March 2015 This experience has informed our proposal of five guiding principles that may be useful for countries to consider as the world sets and moves forward with the post-2015 development agenda. These include: 1) advancing concrete and meaningful equity agendas that drive the post-2015 goals; 2) ensuring that goals to meet Universal Health Coverage (UHC) incorporate real efforts to focus on improving quality and not only quantity of care; 3) bolstering education and the internal research capacity within countries so that they can improve local evidence-based policy-making; 4) promoting intersectoral collaboration to achieve goals, and 5) improving collaborations between multilateral agencies – that are helping to monitor and evaluate progress towards the goals that are set – and the countries that are working to achieve improvements in health within their nation and across the world. Keywords: Post-2015 Development Agenda, Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), Global Health, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), Universal Health Coverage (UHC), Rwanda Copyright: © 2015 by Kerman University of Medical Sciences Citation: Binagwaho A, Scott KW. -

Essential Surgery

DCP3 Series Acknowledgments Disease Control Priorities, third edition (DCP3) compiles We thank the many contractors and consultants the global health knowledge of institutions and experts who provided support to specific volumes in the form of from around the world, a task that required the efforts economic analytical work, volume coordination, chap- of over 500 individuals, including volume editors, ter drafting, and meeting organization: the Center for chapter authors, peer reviewers, advisory committee Disease Dynamics, Economics, and Policy; Center for members, and research and staff assistants. For each Chronic Disease Control; Center for Global Health of these contributions we convey our acknowledge- Research; Emory University; Evidence to Policy Initiative; ment and appreciation. First and foremost, we would Public Health Foundation of India; QURE Healthcare; like to thank our 31 volume editors who provided the University of California, San Francisco; University of intellectual vision for their volumes based on years of Waterloo; University of Queensland; and the World Health professional work in their respective fields, and then Organization. dedicated long hours to reviewing each chapter, pro- We are tremendously grateful for the wisdom and viding leadership and guidance to authors, and fram- guidance provided by our advisory committee to the ing and writing the summary chapters. We also thank editors. Steered by Chair Anne Mills, the advisory com- our chapter authors who collectively volunteered their mittee assures quality and intellectual rigor of the high- time and expertise to writing over 160 comprehensive, est order for DCP3. evidence-based chapters. The U.S. Institute of Medicine, in collaboration We owe immense gratitude to the institutional spon- with the Inter-Academy Medical Panel, coordinated the sor of this effort: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. -

Building from the HIV Response Toward Universal Health Coverage

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Dartmouth Scholarship Faculty Work 8-16-2016 Building from the HIV Response toward Universal Health Coverage Jonathon Jay Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Kent Buse UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland Marielle Hart International HIV/AIDS Alliance/STOP AIDS NOW! Robert Marten Rockefeller Foundation Scott Kellerman Management Sciences for Health See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Virology Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Jay, Jonathon; Buse, Kent; Hart, Marielle; Marten, Robert; Kellerman, Scott; Odetoyinbo, Morolake; Quick, Jonathan D.; Evans, Timothy; Piot, Peter; Dybul, Mark; and Binagwaho, Agnes, "Building from the HIV Response toward Universal Health Coverage" (2016). Dartmouth Scholarship. 2573. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/2573 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Work at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dartmouth Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Jonathon Jay, Kent Buse, Marielle Hart, Robert Marten, Scott Kellerman, Morolake Odetoyinbo, Jonathan D. Quick, Timothy Evans, Peter Piot, Mark Dybul, and Agnes Binagwaho This article is available at Dartmouth Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/2573 POLICY FORUM Building -

Achieving High Coverage in Rwanda's National Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Programme

Lessons fromLessons the from thefield field Achieving high coverage in Rwanda’s national human papillomavirus vaccination programme Agnes Binagwaho,a Claire M Wagner,b Maurice Gatera,c Corine Karema,c Cameron T Nuttd & Fidele Ngaboa Problem Virtually all women who have cervical cancer are infected with the human papillomavirus (HPV). Of the 275 000 women who die from cervical cancer every year, 88% live in developing countries. Two vaccines against the HPV have been approved. However, vaccine implementation in low-income countries tends to lag behind implementation in high-income countries by 15 to 20 years. Approach In 2011, Rwanda’s Ministry of Health partnered with Merck to offer the Gardasil HPV vaccine to all girls of appropriate age. The Ministry formed a “public–private community partnership” to ensure effective and equitable delivery. Local setting Thanks to a strong national focus on health systems strengthening, more than 90% of all Rwandan infants aged 12–23 months receive all basic immunizations recommended by the World Health Organization. Relevant changes In 2011, Rwanda’s HPV vaccination programme achieved 93.23% coverage after the first three-dose course of vaccination among girls in grade six. This was made possible through school-based vaccination and community involvement in identifying girls absent from or not enrolled in school. A nationwide sensitization campaign preceded delivery of the first dose. Lessons learnt Through a series of innovative partnerships, Rwanda reduced the historical two-decade gap in vaccine introduction between high- and low-income countries to just five years. High coverage rates were achieved due to a delivery strategy that built on Rwanda’s strong vaccination system and human resources framework. -

500+ Organizations Launch Global Coalition to Accelerate Access to Universal Health Coverage

12 December 2014 Media Contacts: Rebecca Distler: [email protected] | +1 646 283 4875 Erissa Scalera, The Rockefeller Foundation: [email protected] | +1 212 852 8430 500+ Organizations Launch Global Coalition to Accelerate Access to Universal Health Coverage On first-ever Universal Health Coverage Day, all countries urged to make quality health coverage accessible to everyone, everywhere. NEW YORK, 12 December 2014 – A new global coalition of more than 500 leading health and development organizations worldwide is urging governments to accelerate reforms that ensure everyone, everywhere, can access quality health services without being forced into poverty. The coalition was launched today, on the first-ever Universal Health Coverage Day, to stress the importance of universal access to health services for saving lives, ending extreme poverty, building resilience against the health effects of climate change and ending deadly epidemics such as Ebola. Universal Health Coverage Day marks the two-year anniversary of a United Nations resolution, unanimously passed on 12 December 2012, which endorsed universal health coverage as a pillar of sustainable development and global security. Despite progress in combatting global killers such as HIV/AIDS and vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles, tetanus and diphtheria, the global gap between those who can access needed health services without fear of financial hardship and those who cannot is widening. Each year, 100 million people fall into poverty because they or a family member becomes seriously ill and they have to pay for care out of their own pockets. Around one billion people worldwide can’t even access the health care they need, paving the way for disease outbreaks to become catastrophic epidemics.