Vietnamese Relations By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market Via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation

CHAPTER 7 Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation Phi Vinh Tuong This chapter should be cited as: Phi, Vinh Tuong, 2012. “Developing West-Northern Provinces of Vietnam: Challenge to Integrate with GMS Market via China-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Cooperation.” In Five Triangle Areas in The Greater Mekong Subregion, edited by Masami Ishida, BRC Research Report No.11, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. CHAPTER 7 DEVELOPING WEST-NORTHEN PROVINCES OF VIETNAM: CHALLENGE TO INTEGRATE WITH GMS MARKET VIA CHINA-LAOS-VIETNAM TRIANGLE COOPERATION Phi Vinh Tuong INTRODUCTION The economy of Vietnam has benefited from regional and world markets over the past 20 years of integration. Increasing trade promoted investment, job creation and poverty reduction, but the distribution of trade benefits was not equal across regions. Some remote and mountainous areas, such as the west-northern region of Vietnam, were left at the margin. Even though they are important to the development of Vietnam, providing energy for industrialization, the lack of resource allocation hinders infrastructure development and, therefore, reduces their chances of access to regional and world markets. The initiative of developing one of the northern triangles, which consists of three west-northern provinces of Vietnam, the northern provinces of Laos and a southern part of Yunnan Province in China (we call the northern triangle as CHLV Triangle hereafter), could be a new approach for this region’s development. Strengthening the cooperation and specialization among these provinces may increase the chances of exporting local products with higher value added to regional markets, including the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) and south-western Chinese markets. -

Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin

Journal of chinese humanities 5 (2019) 124-148 brill.com/joch Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin Ge Zhaoguang 葛兆光 Professor of History, Fudan University, China [email protected] Abstract This article is not concerned with the history of aesthetics but, rather, is an exercise in intellectual history. “Illustrations of Tributary States” [Zhigong tu 職貢圖] as a type of art reveals a Chinese tradition of artistic representations of foreign emissaries paying tribute at the imperial court. This tradition is usually seen as going back to the “Illustrations of Tributary States,” painted by Emperor Yuan in the Liang dynasty 梁元帝 [r. 552-554] in the first half of the sixth century. This series of paintings not only had a lasting influence on aesthetic history but also gave rise to a highly distinctive intellectual tradition in the development of Chinese thought: images of foreign emis- saries were used to convey the Celestial Empire’s sense of pride and self-confidence, with representations of strange customs from foreign countries serving as a foil for the image of China as a radiant universal empire at the center of the world. The tra- dition of “Illustrations of Tributary States” was still very much alive during the time of the Song dynasty [960-1279], when China had to compete with equally powerful neighboring states, the empire’s territory had been significantly diminished, and the Chinese population had become ethnically more homogeneous. In this article, the “Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions” [Wanfang zhigong tu 萬方職貢圖] attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 [ca. -

The Zuozhuan Account of the Death of King Zhao of Chu and Its Sources

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 159 August, 2005 The Zuozhuan Account of the Death of King Zhao of Chu and Its Sources by Jens Østergaard Petersen Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Supplied Through the Parthians) from the 1St Century BC, Even Though the Romans Thought Silk Was Obtained from Trees

Chinese Silk in the Roman Empire Trade with the Roman Empire followed soon, confirmed by the Roman craze for Chinese silk (supplied through the Parthians) from the 1st century BC, even though the Romans thought silk was obtained from trees: The Seres (Chinese), are famous for the woolen substance obtained from their forests; after a soaking in water they comb off the white down of the leaves... So manifold is the labor employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman maiden to flaunt transparent clothing in public. -(Pliny the Elder (23- 79, The Natural History) The Senate issued, in vain, several edicts to prohibit the wearing of silk, on economic and moral grounds: the importation of Chinese silk caused a huge outflow of gold, and silk clothes were considered to be decadent and immoral: I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body. -(Seneca the Younger (c. 3 BCE- 65 CE, Declamations Vol. I) The Roman historian Florus also describes the visit of numerous envoys, included Seres (perhaps the Chinese), to the first Roman Emperor Augustus, who reigned between 27 BCE and 14 CE: Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. -

Hosted Au Deposits of the Dian-Qian-Gui Area, Guizhou, and Yunnan Provinces, and Guangxi District, P.R

CHAPTER 3 Geology and Geochemistry of Sedimentary Rock- Hosted Au Deposits of the Dian-Qian-Gui Area, Guizhou, and Yunnan Provinces, and Guangxi District, P.R. China 1 2 2 By Stephen G. Peters , Huang Jiazhan , Li Zhiping , 2 3 Jing Chenggui , and Cai Qiming Open-File Report: 02–131 2002 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Reno Field Office, Mackay School of Mines, MS-176, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557 2Tianjin Geological Academy, Ministry of Metallurgical Industry, 42 Youyi Road, Tianjin City, P.R. China, 300061). 2Kunming Geologic Survey of Ministry of Metallurgical Industry, Kunming, Yunnan. CONTENTS Abstract INTRODUCTION REGIONAL GEOLOGIC SETTING DESCRIPTIONS of Au DEPOSITS Zimudang Au deposit Lannigou Au deposit Banqi Au deposit Yata Au deposit Getang Au deposit Sixianchang Au–Hg deposit Jinya Au deposit Gaolong Au deposit Gedang Au deposit Jinba Au deposit Hengxian Au deposit DISUCSSION and CONCLUSIONS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS REFERENCES 3 96 List of Figures Figure 3-1. Geologic map and distribution of sedimentary rock-hosted Au deposits in the Dian- Qian-Gui area. Figure 3-2. Geologic parameters of the Dian-Qian-Gui area. Figure 3-3. Sedimentary facies in the Dian-Qian-Gui area. Figure 3-4. Geophysical interpretation of shallow crust in the Dian-Qian-Gui area. -

Commissioner Li and Prefect Huang: Sino-Vietnamese Frontier Trade Networks and Political Alliances in the Southern Song

sino-vietnamese trade and alliances james a. anderson Commissioner Li and Prefect Huang: Sino-Vietnamese Frontier Trade Networks and Political Alliances in the Southern Song INTRODUCTION rom the 900s to the 1200s, political loyalties in the upland areas F along the Sino-Vietnamese frontier were a complicated matter. The Dai Viet 大越 kingdom, while adopting elements of the imperial Chinese system of frontier administration, ruled at less of a distance from their upland subjects. Marriage alliances between the local elite and the Ly 李 (1009–1225) and Tran 陳 (1225–1400) royal dynasties helped bind these upland areas more closely to the central court. By contrast, both the Northern and Southern Song courts (960–1279) were preoccupied with their northern frontiers, investing most of the courts’ resources in that region, while relying on a small contingent of officials situated in Yongzhou 邕州 (modern-day Nanning) to pursue imperial aims along the southern frontier. The behavior of the frontier elite was also closely linked to changes in the flow of trade across the Sino-Vietnamese bor- derlands, and the impact of changing patterns in trade will play a role in this study. Broadly speaking, this paper focuses on a triangular re- gion, the base of which stretches from the Song port of Qinzhou 欽州 to the inland frontier region at Longzhou 龍州 (Guangxi). (See the maps provided in the Introduction to this volume.) These two points at either end of the base in this territorial triangle meet at Yongzhou, which was the center of early-Song administration for the Guangnan West circuit (Guangnan xilu 廣南西路). -

Wykorzystanie Biodegradowalnych Polimerów W Rozmnażaniu Ozdobnych Roślin Cebulowych

Inżynieria Ekologiczna Ecological Engineering Vol. 46, Feb. 2016, p. 143–148 DOI: 10.12912/23920629/61477 WYKORZYSTANIE BIODEGRADOWALNYCH POLIMERÓW W ROZMNAŻANIU OZDOBNYCH ROŚLIN CEBULOWYCH Piotr Salachna1 1 Katedra Ogrodnictwa, Wydział Kształtowania Środowiska i Rolnictwa, Zachodniopomorski Uniwersytet Technologiczny w Szczecinie, ul. Papieża Pawła VI 3, 71-459 Szczecin, e-mail: [email protected] STRESZCZENIE Syntetyczne regulatory wzrostu mają negatywny wpływ na środowisko stąd coraz częściej w ogrodnictwie wyko- rzystuje się naturalne biostymulatory. Niektóre naturalne polimery wykazują stymulujący wpływ na wzrost i roz- wój roślin. Związki te mogą być stosowane do tworzenia hydrożelowych otoczek na powierzchni organów roślin- nych w celu ochrony przed niekorzystnym wpływem czynników zewnętrznych. Gatunki eukomis są powszechnie stosowane w tradycyjnej medycynie Afryki Południowej i znajdują szerokie zastosowanie jako ozdobne rośliny cebulowe. Celem badań było określenie wpływu otoczkowania w biopolimerach sadzonek dwułuskowych dwóch odmian eukomis czubatej (‘Sparkling Burgundy’ i ‘Twinkly Stars’) na plon i jakość uzyskanych cebul przybyszo- wych. Sadzonki otoczkowano w 1% roztworze gumy gellanowej (Phytagel) lub 0,5% roztworze oligochitozanu. Stwierdzono, że otoczkowanie sadzonek w gumie gellanowej miało stymulujący wpływ na liczbę i masę cebul przybyszowych. Najsilniejszy system korzeniowy wytworzyły cebule uformowane na sadzonkach otoczkowa- nych w oligochitozanie. Porównując odmiany wykazano, że ‘Sparkling Burgundy’ wytworzyła więcej cebul, które jednocześnie miały większą masę i dłuższe korzenie niż ‘Twinkly Stars’. Słowa kluczowe: eukomis czubata, oligochitozan, guma gellanowa, sadzonki dwułuskowe. THE USE OF BIODEGRADABLE POLYMERS TO PROPAGATION OF ORNAMENTAL BULBOUS PLANTS ABSTRACT Synthesized growth regulators may cause a negative impact on the environment so the use of natural bio-stimula- tors in horticulture is becoming more popular. Some biopolymers can have a stimulating influence on the growth and development of plants. -

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Zev Handel William Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Grainger Lanneau University of Washington Abstract Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Zev Handel Asian Languages and Literature Middle Chinese glottal stop Ying [ʔ-] initials usually develop into zero initials with rare occasions of nasalization in modern day Sinitic1 languages and Sino-Vietnamese. Scholars such as Edwin Pullyblank (1984) and Jiang Jialu (2011) have briefly mentioned this development but have not yet thoroughly investigated it. There are approximately 26 Sino-Vietnamese words2 with Ying- initials that nasalize. Scholars such as John Phan (2013: 2016) and Hilario deSousa (2016) argue that Sino-Vietnamese in part comes from a spoken interaction between Việt-Mường and Chinese speakers in Annam speaking a variety of Chinese called Annamese Middle Chinese AMC, part of a larger dialect continuum called Southwestern Middle Chinese SMC. Phan and deSousa also claim that SMC developed into dialects spoken 1 I will use the terms “Sinitic” and “Chinese” interchangeably to refer to languages and speakers of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. 2 For the sake of simplicity, I shall refer to free and bound morphemes alike as “words.” 1 in Southwestern China today (Phan, Desousa: 2016). Using data of dialects mentioned by Phan and deSousa in their hypothesis, this study investigates initial nasalization in Ying-initial words in Southwestern Chinese Languages and in the 26 Sino-Vietnamese words. -

![Flood Control for the Red River [Vietnam]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8238/flood-control-for-the-red-river-vietnam-678238.webp)

Flood Control for the Red River [Vietnam]

Total Disaster Risk Management - Good Practices - Chapter 3 Vietnam Flood Control for the Red River The Red River, the Delta and Floods The history of the development of Vietnamese civilizations is closely linked to the Red River (Hong River) Delta. As the second largest granary of Vietnam, the Delta holds a significant meaning in the life of the Vietnamese people. This is where approximately 15–20 % of Vietnam’s rice is produced. A population of 17 million now inhabits the 16,500-km2 area of the Red River Delta. The catchment area of the Red River is estimated at 169,000 km2, half of which lies in China. The Red River at Hanoi comprises three major tributary systems, the Da, Thao and Lo Rivers. The river is the source of various positive aspects for human life, such as water resources and rich alluvium (it is called the Red River as the large amount of alluvium it carries colors it red all year round). However, these go hand in hand with a much less expected occurrence: floods. Increased flash floods as a result of deforestation in the upstream parts of the Red River basin, and raised bed levels of the rivers due to the deposition of sediment, are causing higher flood levels, endangering the ever increasing socio-economic value of the capital. The land in low-lying areas of the river delta is protected against flooding by river dyke systems. According to official historical records, in 1108, King Ly Nhan Tong ordered the construction of the first dyke with solid foundations on a large scale aimed at protecting the capital of Thang Long (now Hanoi). -

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

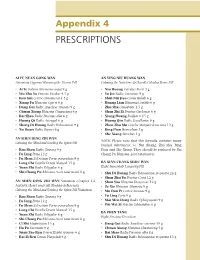

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

Overseas Environmental Measures of Japanese Companies(Vietnam )

Chapter 1 Overview of Environmental Issues and Environmental Conservation Practices in Vietnam This chapter is divided into seven sections that provide basic information necessary for Japanese companies to implement effective environmental measures in Vietnam. Section 1 presents the outline of Vietnam and discusses its relations with Japan and Japanese companies, and Section 2 gives information about environmental problems in the country as they exist now. Section 3 explains the country's environmental policy, legislation, administrative structure, and other related matters. Sections 4 through 6 provide information about the scheme and content of the country's specific environmental regulations designed to deal with water pollution, air pollution, and industrial waste, which are the country's principal environmental challenges and at the same time the problems against which Japanese companies are required to take countermeasures. Finally, Section 7 describes the process of environmental impact assessment required to be performed prior to building industrial plants or other facilities. In addition, Appendix 1 in the references at the end of this report carries the whole text of the Law on Environmental Protection, which was put into effect in January 1994 and constitutes the basis for Vietnam's environmental policy. Appendices 2 through 4 contain excerpts of three pieces of environmental legislation that have a lot to do with Japanese companies doing business in Vietnam. 1 Section 1 Vietnam and Japanese Companies 3 Chapter 1 – Section 1 1. Increasingly Closer Japan-Vietnam Relations Centering in Economy The Socialist Republic of Vietnam (hereinafter called Vietnam), located in the eastern part of the Indochina, has a population of 77 million, the second largest in Southeast Asia after Indonesia. -

The Symbol of the Dragon and Ways to Shape Cultural Identities in Institute Working Vietnam and Japan Paper Series

2015 - HARVARD-YENCHING THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN INSTITUTE WORKING VIETNAM AND JAPAN PAPER SERIES Nguyen Ngoc Tho | University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE 1 CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN VIETNAM AND JAPAN Nguyen Ngoc Tho University of Social Sciences and Humanities Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City Abstract Vietnam, a member of the ASEAN community, and Japan have been sharing Han- Chinese cultural ideology (Confucianism, Mahayana Buddhism etc.) and pre-modern history; therefore, a great number of common values could be found among the diverse differences. As a paddy-rice agricultural state of Southeast Asia, Vietnam has localized Confucianism and absorbed it into Southeast Asian culture. Therefore, Vietnamese Confucianism has been decentralized and horizontalized after being introduced and accepted. Beside the local uniqueness of Shintoism, Japan has shared Confucianism, the Indian-originated Mahayana Buddhism and other East Asian philosophies; therefore, both Confucian and Buddhist philosophies should be wisely laid as a common channel for cultural exchange between Japan and Vietnam. This semiotic research aims to investigate and generalize the symbol of dragons in Vietnam and Japan, looking at their Confucian and Buddhist absorption and separate impacts in each culture, from which the common and different values through the symbolic significances of the dragons are obviously generalized. The comparative study of Vietnamese and Japanese dragons can be enlarged as a study of East Asian dragons and the Southeast Asian legendary naga snake/dragon in a broader sense. The current and future political, economic and cultural exchanges between Japan and Vietnam could be sped up by applying a starting point at these commonalities.