And I Half Turn to Go: Invocatio and Negation of the Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

London Explorer Pass List of Attractions

London Explorer Pass List of Attractions Tower of London Uber Boat by Thames Clippers 1-day River Roamer Tower Bridge St Paul’s Cathedral 1-Day hop-on, hop-off bus tour The View from the Shard London Zoo Kew Gardens Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre Tour Westminster Abbey Kensington Palace Windsor Palace Royal Observatory Greenwich Cutty Sark Old Royal Naval College The Queen’s Gallery Chelsea FC Stadium Tour Hampton Court Palace Household Cavalry Museum London Transport Museum Jewel Tower Wellington Arch Jason’s Original Canal Boat Trip ArcelorMittal Orbit Beefeater Gin Distillery Tour Namco Funscape London Bicycle Hire Charles Dickens Museum Brit Movie Tours Royal Museums Greenwich Apsley House Benjamin Franklin House Queen’s Skate Dine Bowl Curzon Bloomsbury Curzon Mayfair Cinema Curzon Cinema Soho Museum of London Southwark Cathedral Handel and Hendrix London Freud Museum London The Postal Museum Chelsea Physic Garden Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising Pollock’s Toy Museum Twickenham Stadium Tour and World Rugby Museum Twickenham Stadium World Rugby Museum Cartoon Museum The Foundling Museum Royal Air Force Museum London London Canal Museum London Stadium Tour Guildhall Art Gallery Keats House Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art Museum of London Docklands National Army Museum London Top Sights Tour (30+) Palaces and Parliament – Top Sights Tour The Garden Museum London Museum of Water and Steam Emirates Stadium Tour- Arsenal FC Florence Nightingale Museum Fan Museum The Kia Oval Tour Science Museum IMAX London Bicycle Tour London Bridge Experience Royal Albert Hall Tour The Monument to the Great Fire of London Golden Hinde Wembley Stadium Tour The Guards Museum BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Wernher Collection at Ranger’s House Eltham Palace British Museum VOX Audio Guide . -

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture's Showman

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture’s Showman His giant new structure aims to be an Eiffel Tower for New York. Is it genius or folly? February 26, 2018 | By IAN PARKER Stephen Ross, the seventy-seven-year-old billionaire property developer and the owner of the Miami Dolphins, has a winningly informal, old-school conversational style. On a recent morning in Manhattan, he spoke of the moment, several years ago, when he decided that the plaza of one of his projects, Hudson Yards—a Doha-like cluster of towers on Manhattan’s West Side—needed a magnificent object at its center. He recalled telling him- self, “It has to be big. It has to be monumental.” He went on, “Then I said, ‘O.K. Who are the great sculptors?’ ” (Ross pronounced the word “sculptures.”) Before long, he met with Thomas Heatherwick, the acclaimed British designer of ingenious, if sometimes unworkable, things. Ross told me that there was a presentation, and that he was very impressed by Heatherwick’s “what do you call it—Television? Internet?” An adviser softly said, “PowerPoint?” Ross was in a meeting room at the Time Warner Center, which his company, Related, built and partly owns, and where he lives and works. We had a view of Columbus Circle and Central Park. The room was filled with models of Hudson Yards, which is a mile and a half southwest, between Thirtieth and Thirty-third Streets, and between Tenth Avenue and the West Side Highway. There, Related and its partner, Oxford Properties Group, are partway through erecting the complex, which includes residential space, office space, and a mall—with such stores as Neiman Marcus, Cartier, and Urban Decay, and a Thomas Keller restaurant designed to evoke “Mad Men”—most of it on a platform built over active rail lines. -

Ancient Greek Myth and Drama in Greek Cinema (1930–2012): an Overall Approach

Konstantinos KyriaKos ANCIENT GREEK MYTH AND DRAMA IN GREEK CINEMA (1930–2012): AN OVERALL APPROACH Ι. Introduction he purpose of the present article is to outline the relationship between TGreek cinema and themes from Ancient Greek mythology, in a period stretching from 1930 to 2012. This discourse is initiated by examining mov- ies dated before WW II (Prometheus Bound, 1930, Dimitris Meravidis)1 till recent important ones such as Strella. A Woman’s Way (2009, Panos Ch. Koutras).2 Moreover, movies involving ancient drama adaptations are co-ex- amined with the ones referring to ancient mythology in general. This is due to a particularity of the perception of ancient drama by script writers and di- rectors of Greek cinema: in ancient tragedy and comedy film adaptations,3 ancient drama was typically employed as a source for myth. * I wish to express my gratitude to S. Tsitsiridis, A. Marinis and G. Sakallieros for their succinct remarks upon this article. 1. The ideologically interesting endeavours — expressed through filming the Delphic Cel- ebrations Prometheus Bound by Eva Palmer-Sikelianos and Angelos Sikelianos (1930, Dimitris Meravidis) and the Longus romance in Daphnis and Chloë (1931, Orestis Laskos) — belong to the origins of Greek cinema. What the viewers behold, in the first fiction film of the Greek Cinema (The Adventures of Villar, 1924, Joseph Hepp), is a wedding reception at the hill of Acropolis. Then, during the interwar period, film pro- duction comprises of documentaries depicting the “Celebrations of the Third Greek Civilisation”, romances from late antiquity (where the beauty of the lovers refers to An- cient Greek statues), and, finally, the first filmings of a theatrical performance, Del- phic Celebrations. -

Arcelormittal ORBIT

ArcelorMittal ORBIT Like many parents we try pathetically With the help of a panel of experts, to improve our kids by taking them to including Nick Serota and Julia Peyton- see the big exhibitions. We have trooped Jones, we eventually settled on Anish. through the Aztecs and Hockney and He has taken the idea of a tower, and Rembrandt – and yet of all the shows transformed it into a piece of modern we have seen there is only one that really British art. seemed to fire them up. It would have boggled the minds of the I remember listening in astonishment as Romans. It would have boggled Gustave they sat there at lunch, like a bunch of Eiffel. I believe it will be worthy of art critics, debating the intentions of the London’s Olympic and Paralympic Games, artist and the meaning of the works, and worthy of the greatest city on earth. but agreeing on one point: that these In helping us to get to this stage, were objects of sensational beauty. I especially want to thank David McAlpine That is the impact of Anish Kapoor on and Philip Dilley of Arup, and everyone Our ambition is to turn the young minds, and not just on young at the GLA, ODA and LOCOG. I am Stratford site into a place of minds. His show at the Royal Academy grateful to Tessa and also to Sir Robin destination, a must-see item on broke all records, with hundreds of Wales and Jules Pipe for their the tourist itinerary – and we thousands of people paying £12 to see encouragement and support. -

The Art of the Possible the Arcelormittal Orbit, Collective Memory, and Ecological Survival

The Art of the Possible The ArcelorMittal Orbit, collective memory, and ecological survival David Cross [For ‘Regeneration Songs: Sounds of Opportunity and Loss in East London’ Edited by Alberto Duman, Anna Minton, Dan Hancox and Malcolm James London: Repeater Books, September 2018] As the 2012 London Olympics have long since passed from anticipation through lived experience into history, or at least memory, I decided at last to ‘experience’ the ArcelorMittal Orbit in its physical setting. Emerging from Stratford tube station, I tried to reach the Olympic Park without passing through Westfield, Europe’s largest shopping centre. But the pedestrian walkway petered out in a banal and featureless non-place; with no viable way forward, I had to concede, and return to the main concourse. Surrounded by surveillance cameras, I felt self-conscious and began to suspect myself of having criminal thoughts. But with my field of vision dominated by a brilliant screen playing fragments of a disaster movie, interspersed with an advertisement for dairy milk chocolate, it was easy to be distracted. Framed by an avenue of retail façades, my first glimpse of the ArcelorMittal Orbit had the quality of a computer-generated image, a silhouette shimmering faintly in the polluted London air. Having found my bearings, I decided to relax and ‘go with the flow’, allowing my movement to be governed by the urban form. I wandered through the corporate branded environment, a ‘forest of signs’ enjoining me to “Explore, Discover, Experience, Share, Indulge, and Eat”. I went into a stylish boutique café with a ceiling of beaten copper and a display counter of authentic-looking wooden fruit packing crates, where I was served an organic fairtrade coffee and a delicious pain au chocolat, heated and handed to me in a recycled paper bag by someone who seemed so bored or exhausted that they were almost gone. -

My Show Friends!

15 My Show friends! Please see the floor plan on the previous page for stand locations and an alphabetical exhibitor list, and ask one of our Santa’s Little Helpers if you need help with finding the right exhibitors for your Christmas parties. ONE MOORGATE PLACE One Moorgate Place is a beautiful grade ll listed building in the heart of the city. Our range of elegant spaces can cater for up to 600 people. Let us create the perfect A1 atmosphere for your Christmas party. 020 7920 8613 . www.onemoorgateplace.com/christmas2015 CIRQUE LE SOIR Since our inception in 2009, Cirque le Soir has perfected the immersive experience. From events within our venue to hosting the Cirque experience A2 in other event spaces, we can bring a Cirque party to you! 020 7287 8001 . www.cirquelesoir.com/london/corporate BEST PARTIES EVER GROUP Best Parties Ever are the UK’s Leading Christmas Party Supplier, entertaining 170,000 guests at 21 venues including Tobacco Dock. Let us A3 indulge, amaze and excite you with an unforgettably magical experience. 0844 499 4040 . www.bestpartiesever.com D&D LONDON D&D London is a leading restaurant brand with a portfolio of over 30 venues in London, Leeds, Paris, New York and Tokyo. Group bookings, A4 private dining, terrace hire, exclusive hire, we do it all! Come see us. 020 7716 0716 . www.danddlondon.com/events HARBOUR & JONES EVENTS Current Event Caterer of the Year - Harbour & Jones Events caters events of every size and style. Our Event Team can help you plan a truly memorable A5 Christmas event in one of our many unique London venues. -

The Acoustic City

The Acoustic City The Acoustic City MATTHEW GANDY, BJ NILSEN [EDS.] PREFACE Dancing outside the city: factions of bodies in Goa 108 Acoustic terrains: an introduction 7 Arun Saldanha Matthew Gandy Encountering rokesheni masculinities: music and lyrics in informal urban public transport vehicles in Zimbabwe 114 1 URBAN SOUNDSCAPES Rekopantswe Mate Rustications: animals in the urban mix 16 Music as bricolage in post-socialist Dar es Salaam 124 Steven Connor Maria Suriano Soft coercion, the city, and the recorded female voice 23 Singing the praises of power 131 Nina Power Bob White A beautiful noise emerging from the apparatus of an obstacle: trains and the sounds of the Japanese city 27 4 ACOUSTIC ECOLOGIES David Novak Cinemas’ sonic residues 138 Strange accumulations: soundscapes of late modernity Stephen Barber in J. G. Ballard’s “The Sound-Sweep” 33 Matthew Gandy Acoustic ecology: Hans Scharoun and modernist experimentation in West Berlin 145 Sandra Jasper 2 ACOUSTIC FLÂNERIE Stereo city: mobile listening in the 1980s 156 Silent city: listening to birds in urban nature 42 Heike Weber Joeri Bruyninckx Acoustic mapping: notes from the interface 164 Sonic ecology: the undetectable sounds of the city 49 Gascia Ouzounian Kate Jones The space between: a cartographic experiment 174 Recording the city: Berlin, London, Naples 55 Merijn Royaards BJ Nilsen Eavesdropping 60 5 THE POLITIcs OF NOISE Anders Albrechtslund Machines over the garden: flight paths and the suburban pastoral 186 3 SOUND CULTURES Michael Flitner Of longitude, latitude, and -

Birmingham Cover

Warwickshire Cover Online.qxp_Warwickshire Cover 23/09/2015 11:38 Page 1 THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE WARWICKSHIRE ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 358 OCTOBER 2015 MEERA SYAL TALKS ABOUT ANITA AND ME AT THE REP GRAND DESIGNS contemporary home show at the NEC INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS EVENTS FOOD & DRINK & MUCH MORE! HANDBAGGED Moira Buffini’s comedy visits the Midlands interview inside... REP (FP) OCT 2015.qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 10:32 Page 1 Contents October Region 1 .qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 21:49 Page 1 October 2015 Strictly Nasty Craig Revel Horwood dresses for Annie Read the interview on page 42 Jason Donovan Moira Buffini Grand Designs stars in Priscilla Queen Of The talks about Handbagged Kevin McCloud back at the NEC Desert page 27 interview page 11 page 69 INSIDE: 4. News 11. Music 24. Comedy 27. Theatre 44. Dance 51. Film 63. Visual Arts 67. Days Out 81. Food @whatsonbrum @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Birmingham What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Publishing + Online Editor: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 WhatsOn Editorial: Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 MAGAZINE GROUP Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Chris Eldon Lee, Heather Kincaid, Katherine Ewing, Helen Stallard Offices: Wynner House, Managing Director: Paul Oliver Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell Chris Atherton Bromsgrove St, Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 Birmingham B5 6RG This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine. -

Acms Quiz – 2017

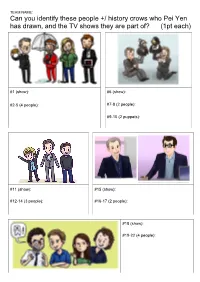

TEAM NAME: Can you identify these people +/ history crows who Pei Yen has drawn, and the TV shows they are part of? (1pt each) #1 (show): #6 (show): #2-5 (4 people): #7-8 (2 people): #9-10 (2 puppets): #11 (show): #15 (show): #12-14 (3 people): #16-17 (2 people): #18 (show): #19-22 (4 people): TEAM NAME: Can you identify these 2005 cartoon boys & their creator? (1pt each) 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 9) 7) 8) 10) TEAM NAME: Round #1 - Shows /15 pts Round #2 - Map /10 pts 1. 1. 2a. 2. 3. 2b. 4. 3a. 5. 6. 3b. 7. 3c. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 6. Round #3 - Fakes /10 pts 7a. 1. 7b. 2. 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10a. 6. 10b. 7. 8. 1 point for a complete right answer, 1/2 point 9. for getting it half right, 0 points for FAILURE* 10. * ignoble failure Round #4 - Award Winners /15 pts Round #5 - Venues /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7a. 7. 8. 7b. 9. 7c. 10. 7d. Round #6 - Names /10 pts 1. 8. 2. 9. 3. 10a. 4. 10b. 5. 10c. 6. 7. PLEASE DRAW US A CAT, IN THE 8. EVENT OF A TIE IT WILL 9. BE USED TO JUDGE 10. THE WINNER Round # /10 pts Round # /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. 10. 10. Round # /10 pts Round # /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. -

PARK DESIGN GUIDE 2018 Drafts 1 and 2 Prepared by Draft 3 and 4 Prepared By

PARK DESIGN GUIDE 2018 Drafts 1 and 2 prepared by Draft 3 and 4 prepared by November 2017 January 2018 Draft Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date 1 for client review GW/RW/LD JR/GW NH HS 22/09/17 2 for final submission (for GW RW SJ HS 10/11/17 internal LLDC use) 3 for consultation AM/RH RH 24/11/17 4 final draft AM/RH RH LG 24/09/18 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 USER GUIDE 6 STREET FURNITURE STRATEGIC GUIDANCE STREET FURNITURE OVERVIEW 54 SEATING 55 PLAY FURNITURE 64 VISION 8 BOUNDARY TREATMENTS 66 INCLUSIVE DESIGN 9 PLANTERS 69 RELEVANT POLICIES AND GUIDANCE 10 BOLLARDS 70 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE AND BIODIVERSITY 12 LIGHTING 72 HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION 14 PUBLIC ART 74 VENUE MANAGEMENT 15 REFUSE AND RECYCLING FACILITIES 75 SAFETY AND SECURITY 16 WAYFINDING 76 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE 17 CYCLE PARKING 80 TEMPORARY AND MOVEABLE FURNITURE 82 CHARACTER AREA DESIGN PRINCIPLES OTHER MISCELLANEOUS FURNITURE 84 QUEEN ELIZABETH OLYMPIC PARK 22 LANDSCAPE AND PLANTING NORTH PARK 23 SOUTH PARK 24 LANDSCAPE SPECIFICATION GUIDELINES 88 CANAL PARK 25 NORTH PARK 90 KEY DESIGN PRINCIPLES 26 SOUTH PARK 95 TREES 108 SURFACE MATERIALS SOIL AND EARTHWORKS 113 SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE SYSTEMS (SUDS) 116 STANDARD MATERIALS PALETTE 30 WATERWAYS 120 PLAY SPACES 31 FOOTPATHS 34 CONSTRUCTION DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT FOOTWAYS 38 CARRIAGEWAYS 40 PARK OPERATIONS AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT 126 KERBS AND EDGING 42 RISK MANAGEMENT 127 SLOPES, RAMPS AND STEPS 45 CONSTRUCTION PLANNING AND MITIGATION 128 DRAINAGE 47 ASSET MANAGEMENT 129 PARKING AND LOADING 49 A PARK FOR THE FUTURE 130 UTILITIES 51 SURFACE MATERIALS MAINTENANCE 52 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GLOSSARY REFERENCES QUEEN ELIZABETH OLYMPIC PARK DESIGN GUIDE INTRODUCTION CONTEXT Occupying more than 100ha, Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park Estate is made Olympic Park lies across the border of four up of development plots which are defined East London boroughs: Hackney, Newham, by Legacy Communities Scheme (LCS). -

APOLLO in ASIA MINOR and in the APOCALYPSE Abstract

Title: CHAOS AND CLAIRVOYANCE: APOLLO IN ASIA MINOR AND IN THE APOCALYPSE Abstract: In the Apocalypse interpreters acknowledge several overt references to Apollo. Although one or two Apollo references have received consistent attention, no one has provided a sustained consideration of the references as a whole and why they are there. In fact, Apollo is more present across the Apocalypse than has been recognized. Typically, interpreters regard these overt instances as slights against the emperor. However, this view does not properly consider the Jewish/Christian perception of pagan gods as actual demons, Apollo’s role and prominence in the religion of Asia Minor, or the complexity of Apollo’s role in imperial propaganda and its influence where Greek religion was well-established. Using Critical Spatiality and Social Memory Theory, this study provides a more comprehensive religious interpretation of the presence of Apollo in the Apocalypse. I conclude that John progressively inverts popular religious and imperial conceptions of Apollo, portraying him as an agent of chaos and the Dragon. John strips Apollo of his positive associations, while assigning those to Christ. Additionally, John’s depiction of the god contributes to the invective against the Dragon and thus plays an important role to shape the social identity of the Christian audience away from the Dragon, the empire, and pagan religion and rather toward the one true God and the Lamb who conquers all. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY CHAOS AND CLAIRVOYANCE: APOLLO IN ASIA MINOR AND IN THE APOCALYPSE SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIBLICAL STUDIES BY ANDREW J.