The Art of the Possible the Arcelormittal Orbit, Collective Memory, and Ecological Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London Explorer Pass List of Attractions

London Explorer Pass List of Attractions Tower of London Uber Boat by Thames Clippers 1-day River Roamer Tower Bridge St Paul’s Cathedral 1-Day hop-on, hop-off bus tour The View from the Shard London Zoo Kew Gardens Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre Tour Westminster Abbey Kensington Palace Windsor Palace Royal Observatory Greenwich Cutty Sark Old Royal Naval College The Queen’s Gallery Chelsea FC Stadium Tour Hampton Court Palace Household Cavalry Museum London Transport Museum Jewel Tower Wellington Arch Jason’s Original Canal Boat Trip ArcelorMittal Orbit Beefeater Gin Distillery Tour Namco Funscape London Bicycle Hire Charles Dickens Museum Brit Movie Tours Royal Museums Greenwich Apsley House Benjamin Franklin House Queen’s Skate Dine Bowl Curzon Bloomsbury Curzon Mayfair Cinema Curzon Cinema Soho Museum of London Southwark Cathedral Handel and Hendrix London Freud Museum London The Postal Museum Chelsea Physic Garden Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising Pollock’s Toy Museum Twickenham Stadium Tour and World Rugby Museum Twickenham Stadium World Rugby Museum Cartoon Museum The Foundling Museum Royal Air Force Museum London London Canal Museum London Stadium Tour Guildhall Art Gallery Keats House Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art Museum of London Docklands National Army Museum London Top Sights Tour (30+) Palaces and Parliament – Top Sights Tour The Garden Museum London Museum of Water and Steam Emirates Stadium Tour- Arsenal FC Florence Nightingale Museum Fan Museum The Kia Oval Tour Science Museum IMAX London Bicycle Tour London Bridge Experience Royal Albert Hall Tour The Monument to the Great Fire of London Golden Hinde Wembley Stadium Tour The Guards Museum BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Wernher Collection at Ranger’s House Eltham Palace British Museum VOX Audio Guide . -

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture's Showman

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture’s Showman His giant new structure aims to be an Eiffel Tower for New York. Is it genius or folly? February 26, 2018 | By IAN PARKER Stephen Ross, the seventy-seven-year-old billionaire property developer and the owner of the Miami Dolphins, has a winningly informal, old-school conversational style. On a recent morning in Manhattan, he spoke of the moment, several years ago, when he decided that the plaza of one of his projects, Hudson Yards—a Doha-like cluster of towers on Manhattan’s West Side—needed a magnificent object at its center. He recalled telling him- self, “It has to be big. It has to be monumental.” He went on, “Then I said, ‘O.K. Who are the great sculptors?’ ” (Ross pronounced the word “sculptures.”) Before long, he met with Thomas Heatherwick, the acclaimed British designer of ingenious, if sometimes unworkable, things. Ross told me that there was a presentation, and that he was very impressed by Heatherwick’s “what do you call it—Television? Internet?” An adviser softly said, “PowerPoint?” Ross was in a meeting room at the Time Warner Center, which his company, Related, built and partly owns, and where he lives and works. We had a view of Columbus Circle and Central Park. The room was filled with models of Hudson Yards, which is a mile and a half southwest, between Thirtieth and Thirty-third Streets, and between Tenth Avenue and the West Side Highway. There, Related and its partner, Oxford Properties Group, are partway through erecting the complex, which includes residential space, office space, and a mall—with such stores as Neiman Marcus, Cartier, and Urban Decay, and a Thomas Keller restaurant designed to evoke “Mad Men”—most of it on a platform built over active rail lines. -

Arcelormittal ORBIT

ArcelorMittal ORBIT Like many parents we try pathetically With the help of a panel of experts, to improve our kids by taking them to including Nick Serota and Julia Peyton- see the big exhibitions. We have trooped Jones, we eventually settled on Anish. through the Aztecs and Hockney and He has taken the idea of a tower, and Rembrandt – and yet of all the shows transformed it into a piece of modern we have seen there is only one that really British art. seemed to fire them up. It would have boggled the minds of the I remember listening in astonishment as Romans. It would have boggled Gustave they sat there at lunch, like a bunch of Eiffel. I believe it will be worthy of art critics, debating the intentions of the London’s Olympic and Paralympic Games, artist and the meaning of the works, and worthy of the greatest city on earth. but agreeing on one point: that these In helping us to get to this stage, were objects of sensational beauty. I especially want to thank David McAlpine That is the impact of Anish Kapoor on and Philip Dilley of Arup, and everyone Our ambition is to turn the young minds, and not just on young at the GLA, ODA and LOCOG. I am Stratford site into a place of minds. His show at the Royal Academy grateful to Tessa and also to Sir Robin destination, a must-see item on broke all records, with hundreds of Wales and Jules Pipe for their the tourist itinerary – and we thousands of people paying £12 to see encouragement and support. -

My Show Friends!

15 My Show friends! Please see the floor plan on the previous page for stand locations and an alphabetical exhibitor list, and ask one of our Santa’s Little Helpers if you need help with finding the right exhibitors for your Christmas parties. ONE MOORGATE PLACE One Moorgate Place is a beautiful grade ll listed building in the heart of the city. Our range of elegant spaces can cater for up to 600 people. Let us create the perfect A1 atmosphere for your Christmas party. 020 7920 8613 . www.onemoorgateplace.com/christmas2015 CIRQUE LE SOIR Since our inception in 2009, Cirque le Soir has perfected the immersive experience. From events within our venue to hosting the Cirque experience A2 in other event spaces, we can bring a Cirque party to you! 020 7287 8001 . www.cirquelesoir.com/london/corporate BEST PARTIES EVER GROUP Best Parties Ever are the UK’s Leading Christmas Party Supplier, entertaining 170,000 guests at 21 venues including Tobacco Dock. Let us A3 indulge, amaze and excite you with an unforgettably magical experience. 0844 499 4040 . www.bestpartiesever.com D&D LONDON D&D London is a leading restaurant brand with a portfolio of over 30 venues in London, Leeds, Paris, New York and Tokyo. Group bookings, A4 private dining, terrace hire, exclusive hire, we do it all! Come see us. 020 7716 0716 . www.danddlondon.com/events HARBOUR & JONES EVENTS Current Event Caterer of the Year - Harbour & Jones Events caters events of every size and style. Our Event Team can help you plan a truly memorable A5 Christmas event in one of our many unique London venues. -

With the London Pass Entry Fee Entry Fee TOP ATTRACTIONS Tower of London + Fast Track Entrance £22.00 £10.00 Westminster Abbey £20.00 £9.00

London Pass Prices correct at 01.04.15 Attraction Entrance Prices FREE ENTRY to the following attractions Normal Adult Normal Child with the London Pass Entry fee Entry fee TOP ATTRACTIONS Tower of London + Fast track entrance £22.00 £10.00 Westminster Abbey £20.00 £9.00 NEW 1 Day Hop on Hop off Bus tour (From 1st October 2015) £22.00 £10.00 Windsor Castle + Fast track entrance £19.20 £11.30 Kensington Palace and The Orangery + Fast track entrance £15.90 FREE Hampton Court Palace + Fast track entrance £17.50 £8.75 17.10 ZSL London Zoo + Fast track entrance £24.30 Under 3 FREE Shakespeare's Globe Theatre Tour & Exhibition £13.50 £8.00 Churchill War Rooms £16.35 £8.15 London Bridge Experience and London Tombs + Fast track entrance £24.00 £18.00 Thames River Cruise £18.00 £9.00 HISTORIC BUILDINGS Tower Bridge Exhibition £9.00 £3.90 Royal Mews £9.00 £5.40 Royal Albert Hall - guided tour £12.25 £5.25 Royal Observatory £7.70 £3.60 Monument £4.00 £2.00 Banqueting House £6.00 FREE Jewel Tower £4.20 £2.50 Wellington Arch £4.30 £2.60 Apsley House £8.30 £5.00 Benjamin Franklin House £7.00 FREE Eltham Palace £13.00 £7.80 The Wernher Collection at Ranger's house £7.20 £4.30 MUSEUMS Imperial War Museum £5.00 £5.00 The London Transport Museum £16.00 FREE Household Cavalry Museum £7.00 £5.00 Charles Dickens Museum £8.00 £4.00 London Motor Museum £30.00 £20.00 Guards Museum £6.00 FREE Cartoon Museum £7.00 FREE Foundling Museum £7.50 FREE Science Museum - IMAX Theatre £11.00 £9.00 Handel House Museum £6.50 £2.00 London Canal Museum £4.00 £2.00 Royal Air -

PARK DESIGN GUIDE 2018 Drafts 1 and 2 Prepared by Draft 3 and 4 Prepared By

PARK DESIGN GUIDE 2018 Drafts 1 and 2 prepared by Draft 3 and 4 prepared by November 2017 January 2018 Draft Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date 1 for client review GW/RW/LD JR/GW NH HS 22/09/17 2 for final submission (for GW RW SJ HS 10/11/17 internal LLDC use) 3 for consultation AM/RH RH 24/11/17 4 final draft AM/RH RH LG 24/09/18 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 USER GUIDE 6 STREET FURNITURE STRATEGIC GUIDANCE STREET FURNITURE OVERVIEW 54 SEATING 55 PLAY FURNITURE 64 VISION 8 BOUNDARY TREATMENTS 66 INCLUSIVE DESIGN 9 PLANTERS 69 RELEVANT POLICIES AND GUIDANCE 10 BOLLARDS 70 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE AND BIODIVERSITY 12 LIGHTING 72 HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION 14 PUBLIC ART 74 VENUE MANAGEMENT 15 REFUSE AND RECYCLING FACILITIES 75 SAFETY AND SECURITY 16 WAYFINDING 76 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE 17 CYCLE PARKING 80 TEMPORARY AND MOVEABLE FURNITURE 82 CHARACTER AREA DESIGN PRINCIPLES OTHER MISCELLANEOUS FURNITURE 84 QUEEN ELIZABETH OLYMPIC PARK 22 LANDSCAPE AND PLANTING NORTH PARK 23 SOUTH PARK 24 LANDSCAPE SPECIFICATION GUIDELINES 88 CANAL PARK 25 NORTH PARK 90 KEY DESIGN PRINCIPLES 26 SOUTH PARK 95 TREES 108 SURFACE MATERIALS SOIL AND EARTHWORKS 113 SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE SYSTEMS (SUDS) 116 STANDARD MATERIALS PALETTE 30 WATERWAYS 120 PLAY SPACES 31 FOOTPATHS 34 CONSTRUCTION DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT FOOTWAYS 38 CARRIAGEWAYS 40 PARK OPERATIONS AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT 126 KERBS AND EDGING 42 RISK MANAGEMENT 127 SLOPES, RAMPS AND STEPS 45 CONSTRUCTION PLANNING AND MITIGATION 128 DRAINAGE 47 ASSET MANAGEMENT 129 PARKING AND LOADING 49 A PARK FOR THE FUTURE 130 UTILITIES 51 SURFACE MATERIALS MAINTENANCE 52 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GLOSSARY REFERENCES QUEEN ELIZABETH OLYMPIC PARK DESIGN GUIDE INTRODUCTION CONTEXT Occupying more than 100ha, Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park Estate is made Olympic Park lies across the border of four up of development plots which are defined East London boroughs: Hackney, Newham, by Legacy Communities Scheme (LCS). -

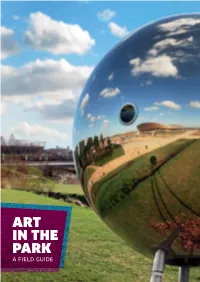

Art in the Park a FIELD GUIDE a Field Guide to Art in the Park 2 3 USING THIS GUIDE

1 ART IN THE PARK A FIELD GUIDE A FIELD GUIDE TO ART IN THE paRK 2 3 USING THIS GUIDE Queen Elizabeth Olympic This book is a field guide to the 26 permanent artworks in the Park. There’s a map at the back and Park was the first Olympic each artwork has a number to help you locate them. Going to find the artworks is just as important as all Park to integrate artworks the reading and looking you can do here. into the landscape right from These artworks have been made to be experienced the start. We worked with in the landscape – up close and from afar. Touch them, sit inside them, run across them, walk beneath established and emerging them. Gaze up, make games, take photographs, put artists, international and local, yourself in their shadow. to create an ambitious, diverse art programme that reflects the Park’s identity as a place for people from around the world and around the corner. Some of these artworks are large and striking, while others are smaller and harder to find. All of them were created specifically for this Park by contemporary artists who worked closely with the architects, designers and construction teams to develop and install their works. Their inspirations are varied: the undulating landscape, buried histories, community memories, song titles, flowing water, energy, ideas of shelter and discovery. Yet all of them are rooted here, each of them sparking new conversations with their immediate environment and this richly textured part of east London. “The trees mark time, the rings 2 3trace landscapes and lives that HistORY TREES have gone before.” Ackroyd and Harvey Ackroyd and Harvey British artists Ackroyd and Harvey created a series of living artworks to mark the main entrances of the Park. -

200 2 Willow Road 157 10 Downing Street 35 Abbey Road Studios 118

200 index 2 Willow Road 157 Fifty-Five 136 10 Downing Street 35 Freedom Bar 73 Guanabara 73 A Icebar 112 Abbey Road Studios 118 KOKO 137 Accessoires 75, 91, 101, 113, 129, 138, Mandarin Bar 90 Ministry of Sound 63 147, 162 Oliver’s Jazz Bar 155 Admiralty Arch 29 Portobello Star 100 Aéroports Princess Louise 83 London Gatwick Airport 171 Proud Camden 137 London Heathrow Airport 170 Purl 120 Afternoon tea 110 Salt Whisky Bar 112 Albert Memorial 88 She Soho 73 Alimentation 84, 101, 147 Shochu Lounge 83 Ambassades de Kensington Palace Simmon’s 83 Gardens 98 The Commercial Tavern 146 Antiquités 162 The Craft Beer Co. 73 Apsley House 103 The Dublin Castle 137 ArcelorMittal Orbit 166 The George Inn 63 Argent 186 The Mayor of Scaredy Cat Town 147 Artisanat 162 The Underworld 137 Auberges de jeunesse 176 Up the Creek Comedy Club 155 Vagabond 84 B Battersea Park 127 Berwick Street 68 Bank of England Museum 44 Big Ben 36 Banques 186 Bloomsbury 76 Banqueting House 34 Bond Street 108 Barbican Centre 51 Boris Bikes 185 Bars et boîtes de nuit 187 Borough Market 61 Admiral Duncan 73 Boxpark 144 Bassoon 39 Brick Lane 142 Blue Bar 90 British Library 77 BrewDog 136 Bunga Bunga 129 British Museum 80 Callooh Callay 146 Buckingham Palace 29 Cargo 146 Bus à impériale 184 Churchill Arms 100 Duke of Hamilton 162 C fabric 51 Cadeaux 39, 121, 155 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782765826774 201 Cadogan Hall 91 Guy Fawkes Night 197 Camden Market 135 London Fashion Week 194, 196 Camden Town 130 London Film Festival 196 Cenotaph, The 35 London Marathon 194 Centres commerciaux 51, 63 London Restaurant Festival 196 Charles Dickens Museum 81 New Year’s Day Parade 194 Cheesegrater 40 New Year’s Eve Fireworks 197 Chelsea 122 Notting Hill Carnival 196 Pearly Harvest Festival 196 Chelsea Flower Show 195 Six Nations Rugby Championship 194 Chelsea Physic Garden 126 St. -

Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Contemporary 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Contemporary

5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument Foreword The Mayor of London's Fourth Plinth has always been a space for experimentation in contemporary art. It is therefore extremely fitting for this exciting exhibition to be opening at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London – an institution with a like-minded vision that continues to champion radical and pioneering art. This innovative and thought-provoking programme has generated worldwide appeal. It has provided both the impetus and a platform for some of London’s most iconic artworks and has brought out the art critic in everyone – even our taxi drivers. Bringing together all twenty-one proposals for the first time, and exhibiting them in close proximity to Trafalgar Square, this exhibition presents an opportunity to see behind the scenes, not only of the Fourth Plinth but, more broadly, of the processes behind commissioning contemporary art. It has been a truly fascinating experience to view all the maquettes side-by-side in one space, to reflect on thirteen years’ worth of work and ideas, and to think of all the changes that have occurred over this period: changes in artistic practice, the city’s government, the growing heat of public debate surrounding national identity and how we are represented through the objects chosen to adorn our public spaces. The triumph of the Fourth Plinth is that it ignites discussion among those who would not usually find themselves considering the finer points of contemporary art. We very much hope this exhibition will continue to stimulate debate and we encourage you to tell us what you think at: www.london.gov.uk/fourthplinth Justine Simons Head of Culture for the Mayor of London Gregor Muir Executive Director, ICA 2 3 5 Dec 2012— 20 Jan 2013 Fourth Plinth: Contemporary Monument One Thing Leads To Another… Michaela Crimmin Trafalgar Square holds interesting tensions. -

To Download Capital Challenge 2017 Route Description

The Inaugural Capital Challenge Saturday 1 st April 2017 START Riverfront Cafe. British Film Institute under Waterloo Bridge TQ308804 Registration Open 08:00 to 09:00 FINISH View Tube Cafe Greenway TQ378838 Open 14:00 to 19:00 Total Distance 27.6 miles Over 40% of London consists of parks and gardens open to the public and with 8.3 million trees there are almost as many as there are people. The walk will allow you to enjoy the biodiversity (and diversity) of this vibrant city and for much of the time you may not even see a car. Not only will you get near to some of the big sights but also lots of lesser attractions that most tourists never get to see. The walk is full of little surprises. Not only will this walk challenge your feet but hopefully your perception of London as well. Of course if it rains you are never too far away from a cafe/pub. Just don’t spend too long there. There is a time limit – finish by 7 p.m.. Practicalities There are plenty of toilets (indicated in route description). Many are free. However it is useful to have a few small coins to hand, especially for the central London area. Toilets get cheaper as the walk progresses so make full use of BFI facilities. There are also several drinking fountains which provide good artesian water. You may want to carry some food and snacks to save time but you are unlikely to starve. A torch is essential especially as the later stages of the walk are along canals. -

Experience New Perspectives FACT SHEET

ArcelorMittal Orbit - Experience New Perspectives FACT SHEET Overview: At the heart of the transformed Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, the ArcelorMittal Orbit is the UK’s tallest sculpture and the only work of art which visitors can enjoy inside and out. Two viewing platforms offer visitors unrivalled views of up to 20 miles across London. Address: ArcelorMittal Orbit, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, Stratford, London E20 2SS Telephone: 0333 800 8099 Email: [email protected] Website: www.arcelormittalorbit.com Open: 5 April 2014 Architects/designers: Sir Anish Kapoor and Cecil Balmond Location: Stratford, East London Nearby attractions: Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park including Copper Box Arena, Aquatics Centre, Lee Valley VeloPark and Lee Valley Hockey and Tennis Centre; Westfield Stratford City Nearby bars and restaurants: The Podium and The Timber Lodge Café both in Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, and The Cow in Westfield Stratford City Background At 114.5m, the ArcelorMittal Orbit is the tallest sculpture in the UK. It is 22 metres taller than the Statue of Liberty and almost six times taller than the Angel of the North. Created by Sir Anish Kapoor and Cecil Balmond as their winning entry to a 2009 competition to design an iconic tower for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Construction began in November 2010 and the structure reached its full height in late 2011. It cost £22.3 million to build - £19.2 million was provided by Lakshmi Mittal of ArcelorMittal, the world’s biggest steelmaker, the remainder from the Greater London Authority. Structurally, the ArcelorMittal Orbit is comprised of two main elements: the trunk which houses the lifts, stairs and viewing platforms and the red steel element which loop around the structure. -

Two for a Million Phoenix Becomes a 2012 Olympics Icon Academic

4 APRIL 2011 THE ARCHER - www.the-archer.co.uk Academic sheds light Phoenix on sacred texts becomes This year is the 400th anniversary of the publication in 1611 of the King James Bible, the most widely read translation of the Bible ever made. To mark this event, a 2012 Professor Bob Owens of the English Department at The Open University, was invited by Oxford University Press to edit the 1611 text of The Gospels for the paperback Olympics series Oxford World’s Classics. The Gospels icon of Matthew, By David Tupman Mark, Luke, and It is a great coup for THE John are regarded ARCHER to be the first of David Evans (left) presenting his first book to Alan Whitewright. by Christians the the UK print media to Photo by Diana Cormack. world over as their reveal that East Finchley’s most precious and favourite cinema will play sacred writings. Two for a million They provide a big part in London’s cul- By Daphne Chamberlain the fullest and tural Olympics. At least two East Finchley people took part in World most memorable Fresh from its own centenary accounts of the life success, the Phoenix will join Book Night on 5 March. Sponsored by booksellers and the 112-metre-tall sculpture - the publishers, and backed by authors and librarians, a mil- and teachings of Jesus Christ, and ArcelorMittal Orbit - as part of an lion books were given away. Each of 20,000 volunteers artistic centrepiece for the Olympic chose one title from a list of 25 and was sent 48 copies of scenes from them have provided park in Stratford.