Michael Crichton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

There Is More Than 3TG the Need for the Inclusion of All Minerals in EU Regulation for Conflict Due Diligence

There is more than 3TG The need for the inclusion of all minerals in EU regulation for conflict due diligence SOMO Paper | January 2015 Companies that use minerals in their products risk International standards and regulation contributing to conflict financing or human rights abuses via their mineral supply chains, especially if upstream Normative standards suppliers are located in conflict zones. This problem is Under the European Convention on Human Rights and being addressed by the European Commission (EC), international human rights law, European member states which has proposed a new regulation with a voluntary have an obligation to ensure that business enterprises due diligence framework to address the risk of financing operating within their jurisdiction do not cause or armed groups and security forces, and mitigate other contribute to human rights violations. The United Nations adverse impacts associated with the extraction, transport Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and trade of four particular minerals: tin, tantalum, and the Organisation for Economic Development and tungsten and gold (3TG). Cooperation’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) set clear standards for business enter- This briefing paper discusses one specific issue in the prises to respect human rights, conduct human rights due proposed EC regulation – the limited number of conflict diligence and implement measures to prevent, address and minerals it includes. It puts the case that the decision to redress any human rights violations.1 The UNGP prescribe focus on the import of minerals and metals containing or that states need to “ensure that their current policies, consisting of 3TG is arbitrary and far too limited to achieve legislation, regulations and enforcement measures are the proposal’s objective of reducing the financing of armed effective in addressing the risks of business involvement groups and security forces through mineral proceeds in in gross human rights abuses”.2 The UNGP have special conflict-affected and high-risk areas. -

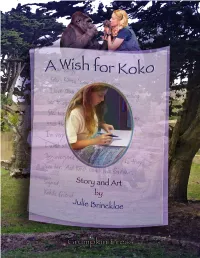

Finding Koko

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

THIS IS CONGO a Film by Daniel Mccabe

PRESENTS THIS IS CONGO A film by Daniel McCabe Running Time: 91 minutes Language: English, French, Swahili and Lingala with English subtitles The Democratic Republic of the Congo / United States / Canada PRESS CONTACT: SALES CONTACT: Dogwoof. Dogwoof Yung Kha +44(0)20 7253 6244 Ana Vicente +44 7977 051577 CONFIDENTIAL: The information contained in this document may contain confidential information and is intended only for the individual(s) or entity(ies) to whom it is addressed. The information contained in this document may also be protected by legal privilege, federal law or other applicable law. Any distribution, dissemination or duplication of this docu- ment is strictly prohibited. SYNOPSIS Why is it that some countries seem to be continually mired in cyclical wars, political instability and economic crises? The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one such a place, a mineral-rich Central African country that, over the last two decades, has seen more than five million conflict-related deaths, multiple regime changes and the wholesale impoverishment of its people. Yet though this ongoing conflict is the world’s bloodiest since WWII, little is known in the West about the players or stakes involved. THIS IS CONGO provides an immersive and unfiltered look into the Africa’s longest continuing conflict and those who are surviving within it. By following four compelling characters — a whistleblower, a patriotic military commander, a mineral dealer and a displaced tailor — the film offers viewers a truly Congolese perspective on the problems that plague this lushly beautiful nation. Colonel ‘Kasongo’, Mamadou Ndala, Mama Romance and Hakiza Nyantaba exemplify the unique resilience of a people who have lived and died through the generations due to the cycle of brutality generated by this conflict. -

It Came from Outer Space: the Virus, Cultural Anxiety, and Speculative

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 It came from outer space: the virus, cultural anxiety, and speculative fiction Anne-Marie Thomas Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Thomas, Anne-Marie, "It came from outer space: the virus, cultural anxiety, and speculative fiction" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4085. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4085 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. IT CAME FROM OUTER SPACE: THE VIRUS, CULTURAL ANXIETY, AND SPECULATIVE FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Anne-Marie Thomas B.A., Texas A&M-Commerce, 1994 M.A., University of Arkansas, 1997 August 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract . iii Chapter One The Replication of the Virus: From Biomedical Sciences to Popular Culture . 1 Two “You Dropped A Bomb on Me, Baby”: The Virus in Action . 29 Three Extreme Possibilities . 83 Four To Devour and Transform: Viral Metaphors in Science Fiction by Women . 113 Five The Body Electr(on)ic Catches Cold: Viruses and Computers . 148 Six Coda: Viral Futures . -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

Michael Crichton and the Distancing of Scientific Discourse

ASp la revue du GERAS 55 | 2009 Varia Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scientific discourse Stéphanie Genty Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/asp/290 DOI: 10.4000/asp.290 ISBN: 978-2-8218-0408-1 ISSN: 2108-6354 Publisher Groupe d'étude et de recherche en anglais de spécialité Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2009 Number of pages: 95-106 ISSN: 1246-8185 Electronic reference Stéphanie Genty, « Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scientific discourse », ASp [Online], 55 | 2009, Online since 01 March 2012, connection on 02 November 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/asp/290 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/asp.290 This text was automatically generated on 2 November 2020. Tous droits réservés Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scie... 1 Apparent truth and false reality: Michael Crichton and the distancing of scientific discourse Stéphanie Genty Introduction 1 This article began as an inquiry into the relation of FASP, or professional-based fiction, to professional reality. I was interested in elucidating the ways in which this reality, which formed the basis for such fiction, was transformed by the writer in his/her work and the reasons behind the transformation. Since my own professional activity has been related to the sciences, I chose to study the novels of Michael Crichton, a commercially-successful writer whose credentials and practice qualify him as an author of professional-based fiction as defined by Michel Petit in his 1999 article “La fiction à substrat professionnel: une autre voie d'accès à l'anglais de spécialité”. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

Menagerie to Me / My Neighbor Be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900

“MENAGERIE TO ME / MY NEIGHBOR BE”: EXOTIC ANIMALS AND AMERICAN CONSCIENCE, 1840-1900 Leslie Jane McAbee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Eliza Richards Timothy Marr Matthew Taylor Ruth Salvaggio Jane Thrailkill © 2018 Leslie Jane McAbee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Leslie McAbee: “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900 (Under the direction of Eliza Richards) Throughout the nineteenth century, large numbers of living “exotic” animals—elephants, lions, and tigers—circulated throughout the U.S. in traveling menageries, circuses, and later zoos as staples of popular entertainment and natural history education. In “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be,” I study literary representations of these displaced and sensationalized animals, offering a new contribution to Americanist animal studies in literary scholarship, which has largely attended to the cultural impact of domesticated and native creatures. The field has not yet adequately addressed the influence that representations of foreign animals had on socio-cultural discourses, such as domesticity, social reform, and white supremacy. I examine how writers enlist exoticized animals to variously advance and disrupt the human-centered foundations of hierarchical thinking that underpinned nineteenth-century tenets of civilization, particularly the belief that Western culture acts as a progressive force in a comparatively barbaric world. Both well studied and lesser-known authors, however, find “exotic” animal figures to be wily for two seemingly contradictory reasons. -

Ndume, and Hayes, J.J

Publications Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Castration as a Viable Alternative to Zeta Male Propagation. J. Primate Behavior [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Identification of POZM-A Novel Protease That is Essential for Degradation of Zeta-Male Protein. Nature [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) A Critical Review of the Color Pink and Anger Management. J. Primate Behavior, 46: 8012-8021. Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) Escalation of Dominance and Aberrant Behavior of Alpha-Males in the Presence of Alpha-Females. J. Primate Behavior, 45: 7384-7390. Ndume, Koko, Gorilla, T.T. (2001) The ëPound Head with Fistí is the Preferred Method of Establishment of Dominance by Alpha- males in Gorilla Society. J. Primate. Behavior, 33: 3753-3762. Graueri, G., Ndume, and Gorilla, E.P. (1996) Rate of Loss of Banana Peel Pigmentation after Banana Consumption. Anal. Chem., 42: 1570-85. Education Ph.D. in Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation 2000 Cincinnati, OH. M.S. in Behavioral Etiquette 1998 Sponge Bob University for Primate Temperament Training. *Discharged from program for non-compliance. Ph.D. in Chemistry 1997 Silverback University, Zaire B.S. in Survival and Chemical Synthesis ? - 1995 The Jungle, Zaire Research Experience Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2001 - Present Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2000 - 2001 Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation, Cincinnati OH 1997 - 2000 Ph.D. -

This Book Served As the Basis for the Script of the Highly Acclaimed Film, “Darkest Hour.” a Short Book, Quick Read

HLG Best Reads of 2018 Kendall Bentz Five Days in London: May 1940 John Lukacs This book served as the basis for the script of the highly acclaimed film, “Darkest Hour.” A short book, quick read. Lukacs’ lively writing gives you a front-row seat to the most consequential decisions of the 20th Century. He makes a compelling case that, through the force of argument and unwavering adherence to core principles, one man single-handedly saved the Western world from fascism. Maddie Boudreau The Next 100 Years George Friedman A very thought-provoking read, especially considering it was written in 2009 and we get to see some of the predictions unfolding today. It’s quite US-centric, but definitely worth picking up! Brittany Burns The Hate U Give Angie Thomas A really grounding and personal view of the Black Lives Matter movement from the perspective of a teenage girl who sees her unarmed friend shot by the police. For those who are a bit lazier, the movie is also excellent. Pachinko Min Jin Lee A really interesting (and heartbreaking) dive into the experience of Koreans living in Japan in the 20th century through the life of a young Korean woman. What’s truly shocking is that a lot of the hardships and discrimination experienced in the early 1900s are still happening today. 1Q84 Haruki Murakami My favorite of Murakami’s intense dream-like epics. It’s a deep and complex web of stories but it’s so worth the effort. Jeremy Button The Men Who United The States Simon Winchester I love this book because it’s about how America went from being an east of the Appalachian Mountains collection of states to becoming a nation as its size grew exponentially. -

The Poison of Misinformation: Analyzing the Use of Science in Science Fiction Novels, in · Original Short Story

THE POISON OF MISINFORMATION: ANALYZING THE USE OF SCIENCE IN SCIENCE FICTION NOVELS, INCLUDING AN ORIGINAL SHORT STORY By CLARA DAWN PIAZZOLA A THESIS Presented to the Department of Biology and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science December 2015 An Abstract of the Thesis of Clara Dawn Piazzola for the degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biology to be taken December 2015 Title: The Poison of Misinformation: Analyzing the use of science in science fiction novels, in · original short story The purpose of this thesis was to read a variety of science fiction novels and understand how the science progresses each novel. For the novels Creature by Peter Benchley, The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton, Dune by Frank Herbert, and The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi, I considered the role of science in relation to plot and character development. For Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton, I analyzed the creativity that the author used with science in addition to the role science played in the novel. For Jaws by Peter Benchley, I researched the accuracy of the science used and determined that the majority was accurate. With all of these analyses in mind, I created a template to guide authors in writing science fiction. Finally, I wrote my own science fiction short story, titled "Poison." ii Copyright Page This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA.