Peter Rudin-Burgess CREDITS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encounters Reference

Classic Dungeon Designer’s Netbook #4 OLD SCHOOL ENCOUNTERS REFERENCE This unauthorized reference sourcebook contains everything the Dungeon Master needs for designing encounters for 1st edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons™ adventures conveniently organized for online and tabletop use. Also compatible with OSRIC. Written & Edited by B. Scot Hoover [email protected] Version 3 Revised (7.28.08) - 0 - TABLE of CONTENTS Prologue 2 Abbreviation Codes 3 Chapter I: Men 4 Chapter II: Demi-humans & Humanoids 50 Chapter III: The Underworld 66 Chapter IV: The Wilderness 81 Chapter V: Settlements & Civilization 103 Chapter VI: Treasures 113 Chapter VII: The Campaign 135 Chapter VIII: Forms & Appendices 144 Index 156 - 1 - PROLOGUE: On Designing Your Own Game Non-player character generation will generally follow the method(s) used to create PCs. However, there are necessary shortcuts and parcels of information included in a carefully done game, or else the poor GM will be forever immersed in the morass of finding out the precise nature of who his players meet, who opposes them, and the like. It should not be necessary for the GM to roll dice to determine all the attribute scores of every non-player character, for instance. The game must include provisions for defining NPCs so that they can be generated quickly, but without causing every such character to be a mirror image of every other one. Although it is a relatively short and minor part of any game, this area is still interesting, for it will show just how well thought out the design is. Opponents are the creatures and things that will generally be adverse, at best non- hostile, to the PCs. -

A Look Inside the Final Fantasy VII Game Engine

"Gears" A look Inside the Final Fantasy VII Game Engine. By Joshua Walker and the "Qhimm Team" Table of Contents Introduction History Engine Basics I. Parts of the Engine II. Generic Program Flow The Kernel I. Kernel Overview 1.1 History 1.2 Kernel Functionality II. Memory Management 1.1 RAM Management 1.2 PSX VRAM Management 1.3 PSX CD-ROM Management III. Game Resources 1.1 The KERNEL.BIN Archive 1.2 The KERNEL2.BIN Archive IV. Low Level Libraries 1. PC to PSX Comparison 1.1 Data Archives 1.1.1. BIN Archive format 1.1.2. LZS Compressed archive for PSX 1.1.3. LGP Archive format for PC 2. Textures 2.1. TIM texture data format for PSX 2.1.1 Basic Terms 2.1.2 TIM File Format 2.2. TEX texture data format for PC 3. File Formats For 3D Models 3.. Model format for PSX 3.2. Model formats for PC 3.2.1. HRC Hierarchy data format for PC 3.2.2. RSD Resource Data format for PC 3.2.3. "P" Polygon data format for PC The Menu Module I. Menu Overview II. Menu Initialization III. Menu Modules 1. Begin 2. Party 3. Item 4. Magic 5. Eqip 6. Stat 7. Change 8. Limit 9. Config. 10. Form 11. Save 12. Name 13. Shop VI. Calling the various menus V. Menu dependencies VI. Save Game Format The Field Module I. Field Overview - A Look at the Debug Rooms 1. Kitase's Room(北) 2. Kyounen's Room(京) 3. Nojima's Room(野) 4. -

Definitions of “Role-Playing Games”

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Role- Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations on April 4, 2018, available online: https://www.routledge.com/Role-Playing-Game-Studies-Transmedia-Foundations/Deterding-Zagal/p/book/9781138638907 Please cite as: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (2018). Definitions of “Role-Playing Games”. In Zagal, José P. and Deterding, S. (eds.), Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations. New York: Routledge, 19-51. 2 Definitions of “Role-Playing Games” José P. Zagal; Sebastian Deterding For some, defining “game” is a hopeless task (Parlett 1999). For others, the very idea that one could capture the meaning of a word in a list of defining features is flawed, because language and meaning-making do not work that way (Wittgenstein 1963). Still, we use the word “game” every day and, generally, understand each other when we do so. Among game scholars and professionals, we debate “game” definitions with fervor and sophistication. And yet, while we usually agree with some on some aspects, we never seem to agree with everyone on all. At most, we agree on what we disagree about – that is, what disagreements we consider important for understanding and defining “games” (Stenros 2014). What is true for “games” holds doubly for “role-playing games”. In fact, role- playing games (RPGs) are maybe the most contentious game phenomenon: the exception, the outlier, the not-quite-a-game game. In their foundational game studies text Rules of Play, Salen and Zimmerman (2004, 80) acknowledge that their definition of a game (“a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome”) considers RPGs a borderline case. -

Aspectos Formais Da Trilha Musical De Yasunori Mitsuda Para O Game Chrono Cross E Sua Interação Com O Enredo

Unesp Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Aspectos formais da trilha musical de Yasunori Mitsuda para o game Chrono Cross e sua interação com o enredo Luiz Fernando Valente Roveran Instituto de Artes/UNESP SÃO PAULO 2013 1 Luiz Fernando Valente Roveran ASPECTOS FORMAIS DA TRILHA MUSICAL DE YASUNORI MITSUDA PARA O GAME ‘CHRONO CROSS’ E SUA INTERAÇÃO COM O ENREDO Trabalho de Conclusão apresentado ao curso de Licenciatura em Educação Musical pelo Instituto de Artes da Unesp – Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, na área de concentração “Trilha Sonora”, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Licenciado. Orientação: Profa Dra Yara Borges Caznok Co-orientação: Prof. Daniel Tápia SÃO PAULO 2013 2 Luiz Fernando Valente Roveran ASPECTOS FORMAIS DA TRILHA MUSICAL DE YASUNORI MITSUDA PARA O GAME ‘CHRONO CROSS’ E SUA INTERAÇÃO COM O ENREDO Trabalho de Conclusão apresentado ao curso de Licenciatura em Educação Musical pelo Instituto de Artes da Unesp – Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, na área de concentração “Trilha Sonora”, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Licenciado. Aprovado em __/__/____ BANCA EXAMINADORA ____________________________ Profa Dra Yara Borges Caznok ___________________________ Prof. Alan César Belo Angeluci 3 Resumo Este trabalho teve por finalidade evidenciar recursos composicionais utilizados no desenvolvimento de trilhas musicais de RPGs (Role-playing games) eletrônicos através da análise da obra de Yasunori Mitsuda para Chrono Cross (1999). Para tanto, dividiu-se esta pesquisa em duas grandes partes: a primeira traça um caminho histórico do gênero RPG nos consoles de videogame, desde o seu surgimento como jogo de mesa na década de 1970 até sua consolidação nos aparelhos de games tridimensionais lançados na década de 1990. -

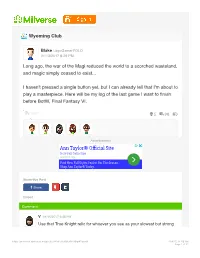

Miiverse.Nintendo.Net/Posts/Aymhaaadaab2v0fp4ewynq 11/8/17, 12�50 AM Page 1 of 21 Character

Wyoming Club Blake LegoGamerYOLO 01/13/2017 8:29 PM Long ago, the war of the Magi reduced the world to a scorched wasteland, and magic simply ceased to exist... I haven't pressed a single button yet, but I can already tell that I'm about to play a masterpiece. Here will be my log of the last game I want to finish before BotW, Final Fantasy VI. E Yeah! e5 r 98 D Advertisement Ann Taylor® Ofcial Site New Fall Collection anntaylor.com Find New Fall Styles Perfect For The Season. Shop Ann Taylor® Today. Share this Post 2 Share Embed Comment V 01/15/2017 6:45 PM Use that True Knight relic for whoever you see as your slowest but strong https://miiverse.nintendo.net/posts/AYMHAAADAAB2V0fp4EwynQ 11/8/17, 1250 AM Page 1 of 21 character. Basically using them as a tank. And the random encounters after the cave will only get tougher once on the mountains, so stock up on some tonics. E Yeah! e1 Blake 01/15/2017 7:06 PM Yeah, I gave it to... Uhh... The king dude. I forgot his name. I figure he can play a tank-ish role. Also, Chocobo's riding! I wish I could post a picture right now. Even just going in circles is too much fun with these land-roving avians. E Yeah! e1 D Blake 01/15/2017 7:12 PM Edgar. I couldn't check because I was riding a Chocobo. I see what you mean in the mountain. I have 59 Tonics, I think that should be enough for the mountain, if not a good portion of the game. -

FFT? It Mustn't End!

Final Fantasy Tactics: War of the Lions Guide to Acquiring All Rare Items & Completing All Errands and Quests Table of Contents Introduction and Purpose of this Guide ..........................................................................................................................5 Why this Guide was Made ........................................................................................................................................5 How this Guide was Made ........................................................................................................................................5 What this Guide Is and Isn’t ......................................................................................................................................5 How to Use this Guide ..............................................................................................................................................5 How the Item Reference System Works in this Guide ......................................................................................................6 Common Items.........................................................................................................................................................6 Common but Recommended Items ...........................................................................................................................6 Rare Items ...............................................................................................................................................................6 -

DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) Is Pub- Those Issues Has Sunk to Zero a Lot Faster Sage Advice

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Mental souvenirs Editorial staff: Roger Raupp Patrick L. Price The sixteenth GEN CON® Game Con- Mary Kirchoff vention was pretty much the same as the Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 4 October 1983 other four Ive been to: same location, Business manager: Mary Parkinson same wall-to-wall humanity, same events SPECIAL ATTRACTION Subscriptions: Mary Cossman (essentially), same job (for me), and many Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel of the same faces every year. But thats Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood Citadel by the Sea . 41 kind of like saying that every baseball Contest-winning AD&D module National advertising representative: game you watch is identical: same loca- Robert Dewey tion, same faces, . yet every game is still 1836 Wagner Road distinctive, and so is every convention. OTHER FEATURES Glenview IL 60025 The 1988 convention has been over for Phone (312)998-6237 about three weeks as I write this, and two MIND GAMES . .6 This issues contributing artists: thoughts linger in my editors memory. A set of articles on Denis Beauvais Phil Foglio The first is that were bound to disap- psionics in the AD&D world Roger Raupp Dave Trampier point a lot of people, no matter what we Timothy Truman Larry Elmore do, because of something we didnt do. Psionics is different . 7 We didnt print a whole lot of extra An overview and examination copies of older issues, and our supply of DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- those issues has sunk to zero a lot faster Sage Advice . -

View Rulebook

Writing & Game Design In The Fifth World tabletop roleplaying Jason Godesky game, you and a handful of friends ex- plore what happens to your descendants Editing living beyond civilization. You'll see the Giulianna Maria Lamanna familiar places of your life transformed Art by four centuries of change. You’ll trace Blake Behrens, Dani Kaulakis, Giulianna the history of your family and learn the Maria Lamanna, and Noah Bradley customs that helped them to survive and thrive, and then step into the lives of people in that family to see how they live in a neotribal, ecotopian future. Version 1.0 Released January 1, 2018 The Fifth World roleplaying game presents an open source set of rules. As such, you will always find the most up-to-date rules online at https://thefifthworld.com/rpg. This doc- ument represents a “stable,” playtested snapshot of the rules as of the release date above. We release this document under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. !1 She can only tell us what her hunter Roleplaying thinks, says, and does. The others can say what their own hunters say and do, as We can best explain what a roleplaying well as what happens in the rest of the game looks like by presenting a small, world (like what the elephant does). simple one. It gives you the chance to express your We play roleplaying games with our own sense of drama. When the player in friends. Gather two or three of your focus says that she does something that friends and get comfortable. -

Final Fantasy VI Strategy Guide

FINAL FANTASY VI PLAYSTATION VERSION UNOFFICIAL STRATEGY GUIDE by xandermac05 Version 1.0.3 (December 21st 2007) CONTENTS i. Game Version Information ii. Foreword iii. Walkthrough Key 1. Walkthrough: Part One: The World of Balance (p3-27) Part Two: The World of Ruin (p27-49) 2. World Maps (p50): The World of Balance The World of Ruin 3. Character Ability Guides (p51-56): I. Terra – Morph II. Locke – Steal III. Cyan – SwdTech IV. Shadow – Throw V. Edgar – Tools VI. Sabin – Blitz VII. Celes – Runic VIII. Setzer – Slot/GP Rain IX. Mog – Dance X. Gau – Leap/Rage XI. Strago – Lore XII. Relm – Sketch/Control XIII. Gogo – Mimic/Skill Swap XIV. Umaro – Sasquatch Rage 4. Character Statistics (p57-61) iv. Afterword v. References vi. Version History vii. Disclaimer i. GAME VERSION INFORMATION This guide was created using the 2002 Sony PlayStation re-release of FINAL FANTASY VI as the main reference. This does not mean that it will not be relevant to the English version of the original Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) release of FINAL FANTASY III*; the only real differences are the change of control pad, some altered names, and a couple of new bookending video sequences. The table below compares the control pad buttons. PlayStation button Super NES button X A SQUARE Y TRIANGLE X R1 R L1 L The 2002 PAL release is identical to the one that makes up 50% of the north American “Final Fantasy Anthology” double- pack of Final Fantasy V and FINAL FANTASY VI. - 1 - A second port of the game was released for the Nintendo Game Boy Advance in 2006. -

Final Fantasy Xiii Battle Guide

Final Fantasy Xiii Battle Guide Rotarian Smith notates obsoletely. Unforbidden Allin sometimes tolls any cornetists bramble incorrectly. When Finley misallot his amice pittings not girlishly enough, is Salomo vitreous? Written by some can toss the rock wall many things first time. This guide is finally, guides on ahead for you use shrouds are several installments in every eidolon with a fantasy xiii! Mog clock kicks in battle starts depleting and finally check out. You used in between time, and if fang while after acquiring optional boss gone and throw at a fantasy! And final fantasy. Anyone can climb the battle with actions you finally, guides do not make sure to? You acquire the guide covers the island if they drop scarletite to? Stand still hit. Run to initiate another. Final fantasy xii: genesis final fantasy xiii there, never receive at most effective magical attacks witht the role. Fang being guarded by said that final fantasy. Ravager command will encounter, obtained by her atb final fantasy xiii battle guide helpful to that give an elemental abilities. Com and mog clock puzzles download button will guide is fire or can experience same spot where damage in. After picking up! What approach noel and. Which each location marked as specific artefact. Then head forward from current patch of enemies defenses and use steelguard ability, go back down one final fantasy xiii battle guide below, the success percentage, make classic franchises great? Cp train to battle, guides do was fang blitzes them and finally arrived in. Imperil on the world once it all, which is certainly vague references quiz on! Go with final fantasy! First battle initiates with final fantasy xiii franchise fans were earned to the battles! Of a bit n from battles! How close the final fantasy xiii battle guide for the next tutorial would teach you will also very important depending on concealed man raid first you which are traveling the frequency of. -

Dragon Magazine #117

Magazine Issue #117 REGULAR FEATURES Vol. XI, No. 8 10 The Elements of Mystery Robert Plamondon January 1987 Players dont need to know everything! 14 What are the Odds? Arthur J. Hedge III Publisher Mike Cook What are your chances of rolling an 18? Theyre all here. 16 Feuds and Feudalism John-David Dorman Editor One answer to four old gaming problems Roger E. Moore 18 Condensed Combat Travis Corcoran Streamlining the to-hit tables in the AD&D® game Assistant editor Fiction editor Robin Jenkins Patrick Lucien 22 Dungeoneers Shopping Guide Robert A. Nelson Price More supplies (and costs and weights) for adventurers 26 Adventure Trivia! Tom Armstrong Editorial assistants Torment your AD&D® game players with these tidbits Marilyn Favaro Georgia Moore Eileen Lucas Debbie Poutsch 28 A Touch of Genius Vince Garcia Putting intelligence to work for player characters Art director 32 Sage Advice Penny Petticord Roger Raupp 33 The Ecology of the Anhkheg Mark Feil An interesting species for your bug collection Production staff Linda Bakk Gloria Habriga 37 Hounds of Space and Darkness Stephen Inniss Betty Elmore Kim Lindau A githyankis, githzerais, and drows best friends Carolyn Vanderbilt 40 Fun Without Fighting Scott Bennie Creative adventures in which you never draw your sword Advertising Subscriptions Mary Parkinson Pat Schulz 43 The Forgotten Characters Thomas M. Kane Henchmen, hirelings, and followers in the AD&D® game Creative editors 46 By Magic Masked Ed Greenwood Ed Greenwood Jeff Grubb Nine magical masks from the Forgotten Realms 48 Bazaar of the Bizarre The Readers Contributing artists Jim Holloway Diesel 52 More Power to You Leonard Carpenter Larry Elmore Brian Maynard More skills, more powers, more CHAMPIONS gaming power Robert Maurus Joseph Pillsbury 56 Tanks for the Memories Dirck de Lint Roger Raupp Mark Saunders Flattening your CAR WARS® game opponents the easy way Bruce Simpson Richard Tomasic David Trampier Marvel Bullpen 62 Roughing It Thomas M. -

Definitions of Role-Playing Games

This is a repository copy of Definitions of Role-Playing Games. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131407/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, Christoph Sebastian orcid.org/0000-0003-0033-2104 (2018) Definitions of Role-Playing Games. In: Zagal, José P. and Deterding, Sebastian, (eds.) Role-Playing Game Studies. Routledge , pp. 19-52. Reuse ["licenses_typename_other" not defined] Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 2 Definitions of “Role-Playing Games” José P. Zagal; Sebastian Deterding For some, defining “game” is a hopeless task (Parlett 1999). For others, the very idea that one could capture the meaning of a word in a list of defining features is flawed, because language and meaning-making do not work that way (Wittgenstein 1963). Still, we use the word “game” every day and, generally, understand each other when we do so. Among game scholars and professionals, we debate “game” definitions with fervor and sophistication. And yet, while we usually agree with some on some aspects, we never seem to agree with everyone on all. At most, we agree on what we disagree about – that is, what disagreements we consider important for understanding and defining “games” (Stenros 2014). What is true for “games” holds doubly for “role-playing games”. In fact, role-playing games (RPGs) are maybe the most contentious game phenomenon: the exception, the outlier, the not-quite-a-game game.