Definitions of Role-Playing Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. Here Be Dragons: the (Pre)History of the Adventure Game

III. Here Be Dragons: the (pre)history of the adventure game The past is like a broken mirror, as you piece it together you cut yourself. Your image keeps shifting and you change with it. MAX PAYNE 2: THE FALL OF MAX PAYNE At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe’s thousand year sleep – or perhaps thousand year germination – between antiquity and the Renaissance, wondrous things were happening. High culture, long dormant, began to stir again. The spirit of adventure grew once more in the human breast. Great cathedrals rose, the spirit captured in stone, embodiments of the human quest for understanding. But there were other cathedrals, cathedrals of the mind, that also embodied that quest for the unknown. They were maps, like the fantastic, and often fanciful, Mappa Mundi – the map of everything, of the known world, whose edges both beckoned us towards the unknown, and cautioned us with their marginalia – “Here be dragons.” (Bradbury & Seymour, 1997, p. 1357)1 At the start of the twenty-first century, the exploration of our own planet has been more or less completed2. When we want to experience the thrill, enchantment and dangers of past voyages of discovery we now have to rely on books, films and theme parks. Or we play a game on our computer, preferably an adventure game, as the experience these games create is very close to what the original adventurers must have felt. In games of this genre, especially the older type adventure games, the gamer also enters an unknown labyrinthine space which she has to map step by step, unaware of the dragons that might be lurking in its dark recesses. -

Downloads/Documents/Tvpn-VW Primer-V1Q308.Pdf

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Piyathasanan, B., Mathies, C., Wetzels, M., Patterson, P. and de Ruyter, K. (2015). A Hierarchical Model of Virtual Experience and Its Influences on the Perceived Value and Loyalty of Customers. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 19(2), pp. 126-158. doi: 10.1080/10864415.2015.979484 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17773/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2015.979484 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] A HIERARCHICAL MODEL OF VIRTUAL EXPERIENCE AND ITS INFLUENCES ON CUSTOMER PERCEIVED VALUE AND LOYALTY Abstract Many businesses use virtual experience (VE) to enhance the overall customer experience, though extant research offers little guidance for how to improve consumers’ VE. This study, anchored in activity theory, examines key drivers of VE and its influences on value perceptions and customer loyalty. -

A Third Age of Avatars Bruce Damer, [email protected] Damer.Com | Digitalspace.Com | Ccon.Org | Biota.Org | Digibarn.Com

A Third Age of Avatars Bruce Damer, [email protected] damer.com | digitalspace.com | ccon.org | biota.org | digibarn.com Ò Started life on a PDP-11 fresh out of high school (1980), programmed graphics, videotext systems, dreamed of self replicating robots on the moon, designed board games, built model space stations. Ò Worked at IBM Research in 1984 (Toronto, New York), introduced to Internet, optical computing. Ò At Elixir Technologies 1987-94, wrote some of first GUI/Windows-Icons Publishing software on the IBM PC platform used 100 countries. Ò Established Contact Consortium in 1995, held first conferences on avatars (Earth to Avatars, Oct 1996) Ò Wrote “Avatars!”in 1997. Hosted and supported 9 conferences until 2003 on various aspects of virtual worlds (AVATARS Conferences, VLearn3D, Digital Biota) Ò Founded DigitalSpace in 1995, produced 3D worlds for government, corporate, university, and industry. Evangelism for Adobe (Atmosphere), NASA (Digital Spaces, open source 3D worlds for design simulation of space exploration) and NIH (learning games for Autism) Ò Established DigibarnComputer Museum (2002) Ò Virtual Worlds Timeline project (2006-2008) to capture and represent the history of the medium Ò The Virtual World, its Origins in Deep Time Ò Text Worlds Ò Graphical Worlds Ò Internet-Connected Worlds Ò The Avatars Cyberconferences Ò Massive Multiplayer Online RPGs Ò Virtual World Platforms Ò Virtual Worlds Timeline Project and Other Research History of Virtual Worlds The Virtual World, its Origins in Deep Time So what is a Virtual World? A place described by words or projected through pictures which creates a space in the imagination real enough that you can feel you are inside of it. -

Soil + Water = Mud It’S Soft, Sticky, Cold, and Probably the Easiest Thing on Earth to Make

The DIY MudMud LayersLayers Soil + water = Mud It’s soft, sticky, cold, and probably the easiest thing on Earth to make. You can play with it in so many creative ways: build a mud house, bake mud pies, and — best of all— squish it between your toes on a hot summer day! But what is mud really made of? This simple experiment will show the different types of soil that makes mud. Materials Instructions • Dirt or mud 1 3 • Water Scoop Mud into container Shake Fill a glass or plastic container • Glass or plastic container Shake the jar until all the about half full of mud. with lid mud and water are mixed. 2 Fill with Water 4 Let Sit Fill the remainder of the jar Leave the jar untouched for with water, nearly to the top, several hours or overnight. but leave room for shaking. The soil sediments will Close tightly with a lid. separate to reveal what your mud is made of. After your jar has settled, you’ll see four distinct layers: water, clay, silt, and sand. Age Level: 3-7 (elementary). Duration: 10 minutes (minimum). Key Definitions: Clay, silt, sand. Objective: To learn and identify different soil layers in mud. 1 Good Mud or Bad Mud? Mud is judged by its ability to grow plants. Most plants thrive in a soil mixture of 20% clay, 40% sand, and 40% silt. If your mud has too much or too little of each type of soil, you can amend the soil with WATER It can mix with soil to organic material, such make mud but the soil as compost, to help your won’t dissolve. -

Mythic: Dynamic Role-Playing

TM Create dynamic role-playing adventures without preparation For use as a stand-alone game or as a supplement for other systems TM Adventure Generator Role Playing System by Tom Pigeon Published by Word Mill Publishing Credits “To help, to continually help and share, that is the sum of all knowledge; that is the meaning of art.” Eleonora Duse The author extends his heartfelt thanks to those friendly souls who helped make this book come true. Without contributors, playtesters, friends, helpful advice, guidance and criticism, there would be no Mythic. ARTISTS MORAL SUPPORT RyK Productions My wife, Jennifer, who believes all things are possible. To contact RyK, you can send email to [email protected], or visit Also, my daughter Ally, just because she’s so darn cute. their webpage at www.ryk.nl RyK Productions is responsible for artwork on pages: 12, 16, TECHNICAL SUPPORT 28, 37, 64, 70, 77, 87, 89, 95, 96, 97, 99, & 119 Apple, for making such an insanely great computer. Karl Nordman OTHER FORMS OF SUPPORT To contact Karl, send email to [email protected]. View Word Mill Publishing, my daytime job. his work on the web at www.angelfire.com/art/xxtremelygraphic/ Karl North is responsible for artwork on pages: 8, 19, 32, 34, 41, 47, 50, 57, 60 PRINTING W RDS Printing in Ontario, California. Thanks to Bob for his W guidance and for investing in technology that allows for the production of digital print-on-demand products. Word Mill Publishing 5005 LaMart Dr. #204 • Riverside, CA 92507 PLAYTESTERS [email protected] • www.mythic.wordpr.com A host of online and real-time gamers whose names are lost Mythic © Copyright 2003 by Tom Pigeon and Word Mill Publishing. -

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

Understanding Visual Novel As Artwork of Visual Communication Design

MUDRA Journal of Art and Culture Volume 32 Nomor 3, September 2017 292-298 P-ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Understanding Visual Novel as Artwork of Visual Communication Design DENDI PRATAMA, WINNY GUNARTI W.W, TAUFIQ AKBAR Departement of Visual Communication Design, Fakulty of Language and Art Indraprasta PGRI. University, Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia [email protected] Visual Novel adalah sejenis permainan audiovisual yang menawarkan kekuatan visual melalui narasi dan karakter visual. Data dari komunitas pengembang Visual Novel (VN) Project Indonesia menunjukkan masih terbatasnya pengembang game lokal yang memproduksi Visual Novel Indonesia. Selain itu, produksi Visual Novel Indonesia juga lebih banyak dipengaruhi oleh gaya anime dan manga dari Jepang. Padahal Visual Novel adalah bagian dari produk industri kreatif yang potensial. Studi ini merumuskan masalah, bagaimana memahami Visual Novel sebagai karya seni desain komunikasi visual, khususnya di kalangan mahasiswa? Penelitian ini merupakan studi kasus yang dilakukan terhadap mahasiswa desain komunikasi visual di lingkungan Universitas Indraprasta PGRI Jakarta. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan masih rendahnya tingkat pengetahuan, pemahaman, dan pengalaman terhadap permainan Visual Novel, yaitu di bawah 50%. Metode kombinasi kualitatif dan kuantitatif dengan pendekatan semiotika struktural digunakan untuk menjabarkan elemen desain dan susunan tanda yang terdapat pada Visual Novel. Penelitian ini dapat menjadi referensi ilmiah untuk lebih mengenalkan dan mendorong pemahaman tentang Visual Novel sebagai karya seni Desain Komunikasi Visual. Selain itu, hasil penelitian dapat menambah pengetahuan masyarakat, dan mendorong pengembangan karya seni Visual Novel yang mencerminkan budaya Indonesia. Kata kunci: Visual novel, karya seni, desain komunikasi visual Visual Novel is a kind of audiovisual game that offers visual strength through the narrative and visual characters. -

CONJECTURE GAMES PRESENTS: Conjectural Roleplaying Gamemaster

CONJECTURE GAMES PRESENTS: CRGE conjectural roleplaying gamemaster emulator By Zach Best Artwork by Matthew Vasey The Helldragon (order #6976544) “If everyone is thinking alike, then somebody isn’t thinking.” – George S. Patton Dedicated to Katie. Who shares every step with me. Written by Zach Best Artwork by Matthew Vasey Published by Conjecture Games (www.conjecturegames.com) Special Thanks to Alex Yari, Francis Flammang, David Dankel, Nicky Tsouklais, Matthew Mooney, Aaron Zeitler, Kenny Norris, Jimmy Williams, and Deathworks for playtesting, editing, and general commenting. Very Special Thanks to Chris Stieha for being the first and most thorough playtester an indie game designer could ever ask for. All text is © Zach Best (2014). All artwork is © Matthew Vasey (2014) and used with permission for this work. The mention of or reference to any company or product in these pages is not a challenge to the trademark or copyright concerned. 2 The Helldragon (order #6976544) Table of Contents What is CRGE? pg. 4 Loom of Fate – Binary GM Emulator, pg. 6 The Surge Count, pg. 8 Unexpectedly Explanations, pg. 10 Loom of Fate Examples, pg. 11 Loom of Fate Tutorial, pg. 13 Conjured Threads – Story Indexing Game Engine, pg. 14 Stage of the Scene, pg. 16 CRGE Scene Setup, pg. 18 Bookkeeping, pg. 18 Storyspinning – Frameworks for CRGE, pg. 20 Vignette Framework, pg. 21 Vignette Framework Tutorial, pg. 23 Tapestry –Multiplayer CRGE Module, pg. 24 Appendix I (Tables), pg. 27 Appendix II (Vignette Framework Tutorial Example), pg. 28 3 The Helldragon (order #6976544) What is CRGE? Conjecture The Conjectural Roleplaying Gamemaster “Is the door locked?” This is a very simple Emulator (“CRGE”) is a supplement for any pen question applicable to many RPG adventures. -

Role Playing Games Role Playing Computer Games Are a Version Of

Role Playing Games Role Playing computer games are a version of early non-computer games that used the same mechanics as many computer role playing games. The history of Role Playing Games (RPG) comes out of table-top games such as Dungeons and Dragons. These games used basic Role Playing Mechanics to create playable games for multiple players. When computers and computer games became doable one of the first games (along with Adventure games) to be implemented were Role Playing games. The core features of Role Playing games include the following features: • The game character has a set of features/skills/traits that can be changed through Experience Points (xp). • XP values are typically increased by playing the game. As the player does things in the game (killing monsters, completing quests, etc) the player earns XP. • Player progression is defined by Levels in which the player acquires or refines skills/traits. • Game structure is typically open-world or has open-world features. • Narrative and progress is normally done by completing Quests. • Game Narrative is typically presented in a non-linear quests or exploration. Narrative can also be presented as environmental narrative (found tapes, etc), or through other non-linear methods. • In some cases, the initial game character can be defined by the player and the initial mix of skills/traits/classes chosen by the player. • Many RPGs require a number of hours to complete. • Progression in the game is typically done through player quests, which can be done in different order. • In Action RPGs combat is real-time and in turn-based RPGs the combat is turn-based. -

Permadeath in Dayz

Fear, Loss and Meaningful Play: Permadeath in DayZ Marcus Carter, Digital Cultures Research Group, The University of Sydney; Fraser Allison, Microsoft Research Centre for Social NUI, The University of Melbourne Abstract This article interrogates player experiences with permadeath in the massively multiplayer online first-person shooter DayZ. Through analysing the differences between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ instances of permadeath, we argue that meaningfulness – in accordance with Salen & Zimmerman’s (2003) concept of meaningful play – is a critical requirement for positive experiences with permadeath. In doing so, this article suggests new ontologies for meaningfulness in play, and demonstrates how meaningfulness can be a useful lens through which to understand player experiences with negatively valanced play. We conclude by relating the appeal of permadeath to the excitation transfer effect (Zillmann 1971), drawing parallels between the appeal of DayZ and fear-inducing horror games such as Silent Hill and gratuitously violent and gory games such as Mortal Kombat. Keywords DayZ, virtual worlds, meaningful play, player experience, excitation transfer, risk play Introduction It's truly frightening, like not game-frightening, but oh my god I'm gonna die-frightening. Your hands starts shaking, your hands gets sweaty, your heart pounds, your mind is racing and you're a wreck when it's all over. There are very few games that – by default – feature permadeath as significantly and totally as DayZ (Bohemia Interactive 2013). A new character in this massively multiplayer online first- person shooter (MMOFPS) begins with almost nothing, and must constantly scavenge from the harsh zombie-infested virtual world to survive. A persistent emotional tension accompanies the requirement to constantly find food and water, and a player will celebrate the discovery of simple items like backpacks, guns and medical supplies. -

Virtual Worlds, Real Leaders: Online Games Put the Future of Business Leadership on Display

cyan mag yelo black MAC Virtual Worlds, Real Leaders: Online games put the future of business leadership on display A Global INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION NEW ORCHARD ROAD, ARMONK, NY 10504 Innovation ® © International Business Machines Corporation 2007 Outlook All Rights Reserved 2.0 Report SERIOSITY, INC. 2370 WATSON CT., SUITE 110, PALO ALTO, CA 94303 ™ 881832IMPO.Cover1832IMPO.Cover NNC4C4 66/20/07/20/07 112:15:522:15:52 AAMM cyan mag yelo black MAC 881832IMPO.Cover1832IMPO.Cover NNC2C2 66/20/07/20/07 112:16:082:16:08 AAMM mag yelo CG11 MAC GIO 2.0 Report “ If you want to see what business leadership may look like in three to fi ve years, look at what’s happening in online games.” — Byron Reeves, Ph.D.,≠ the Paul C. Edwards Professor of Communication at Stanford University and Co-founder of Seriosity, Inc. 1 881832IMPO.Text1832IMPO.Text NN0101 66/20/07/20/07 112:51:412:51:41 AAMM cyan mag yelo black MAC Game On As the business world becomes more distributed and virtual, do online games offer lessons on the future of leadership? 2 881832IMPO.Text1832IMPO.Text NN0202 66/20/07/20/07 112:51:422:51:42 AAMM cyan yelo black CG11 MAC GIO 2.0 Report What’s next? It’s the simple question that businesses spend millions trying to answer every year, all with the goal of learning what the business world of the future will look like. But there are some elements of this future that are already falling into place. For example, we know that business is becoming increasingly global. -

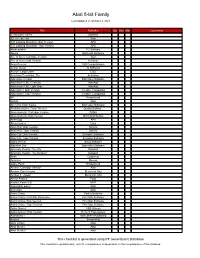

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database.