Downloaded License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

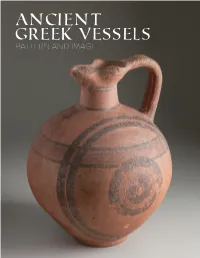

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Dottorato in Scienze Storiche, Archeologiche E Storico-Artistiche

DOTTORATO IN SCIENZE STORICHE, ARCHEOLOGICHE E STORICO-ARTISTICHE Coordinatore prof. Francesco Caglioti XXX ciclo Dottorando: Luigi Oscurato Tutor: prof. Alessandro Naso Tesi di dottorato: Il repertorio formale del bucchero etrusco nella Campania settentrionale (VII – V secolo a.C.) 2018 Il repertorio formale del bucchero etrusco nella Campania settentrionale (VII – V secolo a.C.) Sommario Introduzione ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Storia degli studi sul bucchero rinvenuto in Campania ...................................................................... 8 1. I siti e i contesti ............................................................................................................................ 16 1.1 Capua .................................................................................................................................... 18 1.2 Calatia ................................................................................................................................... 28 1.3 Cales ...................................................................................................................................... 31 1.4 Cuma ..................................................................................................................................... 38 1.5 Il kolpos kymaios ................................................................................................................... 49 2. Catalogo -

Kourimos Parthenos

KOURIMOS PARTHENOS The fragments of an oinochoe ' illustrated here preserve for us the earliest known representation in any medium of the dress and the masks worn by actors in Attic tragedy.2 The style of the vase suggests a date in the neighborhood of 470: 3 a time, that is, when both Aischylos and Sophokles 4 were active in the theatre. Thus, even though our fragments may not shed much new light on the " dark history of the IInv. No. P 11810. Three fragments, mended from five. Height; a, 0.073 m.; b, 0.046 m.; c, 0.065 m. From a round-bodied oinochoe, Beazley Shape III; fairly thin fabric, excellent glaze; relief contour except for the mask; sketch lines on the boy's body. The use of added color is described below, p. 269. For the lower border, a running spiral, with small loops between the spirals. Inside, dull black to brown glaze wash. The fragments were found just outside the Agora Excava- tions, near the bottom of a modern sewer trench along the south side of the Theseion Square, some 200 m. to the south of the temple, at a depth of about 3 m. below the street level. 2 For the fifth century, certainly, relevant comparative material has been limited to three pieces: the relief from the Peiraeus, now in the National Museum, Athens (N. M. 1500; Svoronos, Athener Nationalmuseum, pl. 82), which shows three actors, two of them carrying masks, approaching a reclining Dionysos; the Pronomos vase in Naples (Furtwangler-Reichhold, pls. 143-145), with its elaborate preparations for a satyr-play; and the pelike in Boston, by the Phiale painter (Att. -

Veiling, Αίδώς, and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias Author(S): Douglas L

Edinburgh Research Explorer Veiling, , and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias Citation for published version: Cairns, D 1996, 'Veiling, , and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias', Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 116, pp. 152-7. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/631962> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Journal of Hellenic Studies Publisher Rights Statement: © Cairns, D. (1996). Veiling, , and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 116, 152-7 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Veiling, αίδώς, and a Red-Figure Amphora by Phintias Author(s): Douglas L. Cairns Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 116 (1996), pp. 152-158 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/631962 . Accessed: 16/12/2013 09:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . -

Evaluation of Attic Vase Painting in the Context of Art of Painting

_____________________________________________________ART-SANAT 7/2017_____________________________________________________ EVALUATION OF ATTIC VASE PAINTING IN THE CONTEXT OF ART OF PAINTING ÜFTADE MUŞKARA Assist. Prof., Kocaeli University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Properties [email protected] SERPİL ŞAHİN Res. Assist., Kocaeli University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Painting Department ABSTRACT The attribution of vases to particular individual hands based on the signatures of painters or potters on the vases, the connoisseurship, obtained too much importance especially in the case of Athenian black figure and red figure pottery. It is because; through close examination of details of style it becomes possible to establish the interaction between “artists” and a sequential chronology for vases of black figure and red figure techniques. But some scholars have raised doubts on the limits of such studies. Re- examination of our perception of artist in connection with the attribution studies for Attic figured pottery and the idea supporting connoisseurship are necessary. Determination of figured pottery from a canvas painter’s point of expertise could illuminate the limitations and real context of attribution studies. Keywords: Attic vase painters, attribution studies, the connoisseurship, Morellian method. ATTİK VAZO RESMİNİN RESİM SANATI BAĞLAMINDA DEĞERLENDİRİLMESİ ÖZ Arkeolojide, Attik siyah figür ve kırmızı figür vazolarının vazolar üzerindeki çömlekçi ya da ressam imzalarından yola çıkarak özellikle belirli bireylere, ressamlara, atfedilmesi çok önem taşıyan çalışmalardır. Bunun nedeni, vazo resimlerinin detaylı incelenmesi ve stil kritiği ile ressamlar arasında ilişkiyi kurmak ve siyah figür ve kırmızı figür vazolar için bir kronoloji oluşturmanın mümkün olmasıdır.Ancak bu alanda çalışan bazı bilim insanlarının, çalışmaların sınırları ile ilgili şüpheleri vardır. -

Attic Black Figure from Samothrace

ATTIC BLACK FIGURE FROM SAMOTHRACE (PLATES 51-56) 1 RAGMENTS of two large black-figure column-kraters,potted and painted about j1t the middle of the sixth century, have been recovered during recent excavations at Samothrace.' Most of these fragments come from an earth fill used for the terrace east of the Stoa.2 Non-joining fragments found in the area of the Arsinoeion in 1939 and in 1949 belong to one of these vessels.3 A few fragments of each krater show traces of burning, for either the clay is gray throughout or the glaze has cracked because of intense heat. The surface of many fragments is scratched and pitted in places, both inside and outside; the glaze and the accessory colors, especially the white, have sometimes flaked. and the foot of a man to right, then a woman A. Column krater with decoration continuing to right facing a man. Next is a man or youtlh around the vase. in a mantle facing a sphinx similar to one on a 1. 65.1057A, 65.1061, 72.5, 72.6, 72.7. nuptial lebes in Houston by the Painter of P1. 51 Louvre F 6 (P1. 53, a).4 Of our sphinx, its forelegs, its haunches articulated by three hori- P.H. 0.285, Diam. of foot 0.203, Th. at ground zontal lines with accessory red between them, line 0.090 m. and part of its tail are preserved. Between the Twenty-six joining pieces from the lower forelegs and haunches are splashes of black glaze portion of the figure zone and the foot with representing an imitation inscription. -

Epilykos Kalos

EPILYKOS KALOS (PLATES 63 and 64) N TWO EARLIERPAPERS, the writerattempted to identifymembers of prominent Athenian families in the late 6th century using a combinationof kalos names and os- traka.1 In the second of these studies, it was observed that members of the same family occurredin the work of a single vase painter,2whether praised as kalos or named as partici- pant in a scene of athletics or revelry.3The converse,i.e. that the same individual may be namedon vases by painterswho, on the basis of stylistic affinities,should belong to the same workshop,seems also to be true.4The presentpaper tries to demonstrateboth these proposi- tions by linking membersof another importantfamily, the Philaidai, to a circle of painters on whose vases they appear. The starting point is Epilykos, who is named as kalos 19 times in the years ca. 515- 505, 14 of them on vases by a single painter, Skythes.5Of the other 5, 2 are cups by the Pedieus Painter, whom Beazley considered might in fact be Skythes late in the latter's career;61 is a cup linked to Skythes by Bloesch,7 through the potter work, and through details of draughtsmanship,by Beazley;8 1 is a cup placed by Beazley near the Carpenter Painter;9and the last is a plastic aryballos with janiform women's heads, which gives its name to Beazley's Epilykos Class.10 The close relationshipof Epilykos and Skythesis especiallystriking in view of Skythes' small oeuvre, so that the 14 vases praising Epilykos accountfor fully half his total output. -

Thesis Front Matter

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Prostitute and Her Headdress: the Mitra, Sakkos and Kekryphalos in Attic Red-figure Vase-painting ca. 550-450 BCE by Marina Fischer A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND ROMAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2008 © Marina Fischer 2008 ISBN:ϵϳϴͲϬͲϰϵϰͲϯϴϮϲϰͲϲ Abstract This study documents the problematic headdress iconography of Attic Red-figure vase-painting ca. 550-450 BCE. The findings demonstrate that more prostitutes than wives, or any other female figures, are illustrated with the mitra (turban), sakkos (sack) and kekryphalos (hair-net). These headdresses were prostitutes’ common apparel as well as their frequent attributes and social markers. The study also shows that prostitutes were involved in manufacturing of textiles, producing the headdresses on the small sprang hand frames chosen for their practicality, convenience and low cost. In this enquiry, two hundred and thirty (230) fully catalogued and thoroughly analyzed images include twenty (20) such scenes, in addition to two hundred and ten (210) depicting prostitutes wearing the headdresses. This iconography is the primary evidence on which the study’s conclusions are based. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the University of Calgary Staff Tuition Support Program for their generous contributions, the Department of Greek and Roman Studies for their consideration and understanding of my demanding schedule, Geraldine Chimirri-Russell for inspiration, Dr. Mark Golden for support, and above all Dr. Lisa Hughes for her thoughtfulness, thoroughness and encouragement. -

This Pdf of Your Paper in Athenian Potters and Painters Volume III Belongs to the Publishers Oxbow Books and It Is Their Copyright

This pdf of your paper in Athenian Potters and Painters Volume III belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright. As author you are licenced to make up to 50 offprints from it, but be- yond that you may not publish it on the World Wide Web until three years from publication (August 2017), unless the site is a limited access intranet (password protected). If you have queries about this please contact the editorial department at Oxbow Books (editorial@ oxbowbooks.com). An offprint from Athenian Pot ters and Painters Volume III edited by John H. Oakley Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-663-9 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-664-6 © Oxbow Books 2014 Oxford & Philadelphia www.oxbowbooks.com Published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by OXBOW BOOKS 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford OX1 2EW and in the United States by OXBOW BOOKS 908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083 © Oxbow Books and the individual authors 2014 Hardcover Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-663-9 Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78297-664-6 A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2010290514 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing. Printed in the United Kingdom by Short Run Press, Exeter For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact: UNITED KINGDOM Oxbow Books Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) -

Greek Dramatic Monuments from the Athenian Agora and Pnyx

GREEK DRAMATIC MONUMENTS FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA AND PNYX (PLATES 65-68) T HE excavations of the Athenian Agora and of the Pnyx have produced objects dating from the early fifth century B.C. to the fifth century after Christ which can be termed dramatic monuments because they represent actors, chorusmen, and masks of tragedy, satyr play and comedy. The purpose of the present article is to interpret the earlier part of this series from the point of view of the history of Greek drama and to compare the pieces with other monuments, particularly those which can be satisfactorily dated.' The importance of this Agora material lies in two facts: first, the vast majority of it is Athenian; second, much of it is dated by the context in which it was found. Classical tragedy and satyr play, Hellenistic tragedy and satyr play, Old, Middle and New Comedy will be treated separately. The transition from Classical to Hellenistic in tragedy or comedy is of particular interest, and the lower limit has been set in the second century B.C. by which time the transition has been completed. The monuments are listed in a catalogue at the end. TRAGEDY AND SATYR PLAY CLASSICAL: A 1-A5 HELLENISTIC: A6-A12 One of the earliest, if not the earliest, representations of Greek tragedy is found on the fragmentary Attic oinochoe (A 1; P1. 65) dated about 470 and painted by an artist closely related to Hermonax. Little can be added to Miss Talcott's interpre- tation. The order of the fragments is A, B, C as given in Figure 1 of Miss T'alcott's article. -

Naukratis: Greek Diversity in Egypt

Naukratis: Greek Diversity in Egypt Studies on East Greek Pottery and Exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean Edited by Alexandra Villing and Udo Schlotzhauer The British Museum Research Publication Number 162 Publishers The British Museum Great Russell Street London WC1B 3DG Series Editor Dr Josephine Turquet Distributors The British Museum Press 46 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3QQ Naukratis: Greek Diversity in Egypt Studies on East Greek Pottery and Exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean Edited by Alexandra Villing and Udo Schlotzhauer Front cover: Fragment of North Ionian black-figure amphora (?) from Naukratis. British Museum GR 1886.4-1.1282 (Vase B 102.33) ISBN-13 978-086159-162-6 ISBN-10 086159-162-3 ISSN 0142 4815 © The Trustees of the British Museum 2006 Note: the British Museum Occasional Papers series is now entitled British Museum Research Publications.The OP series runs from 1 to 150, and the RP series, keeping the same ISSN and ISBN preliminary numbers, begins at number 151. For a complete catalogue of the full range of OPs and RPs see the series website: www/the britishmuseum.ac.uk/researchpublications or write to: Oxbow Books, Park End Place Oxford OX1 1HN, UK Tel:(+44) (0) 1865 241249 e mail [email protected] website www.oxbowbooks.com or The David Brown Book Co PO Box 511, Oakville CT 06779, USA Tel:(+1) 860 945 9329;Toll free 1 800 791 9354 e mail [email protected] Printed and bound in UK by Latimer Trend & Co. Ltd. Contents Contributors v Preface vii Naukratis and the Eastern Mediterranean: Past, Present and -

Painted and Written References of Potters and Painters to Themselves and Their Colleagues

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC) Stissi, V.V. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stissi, V. V. (2002). Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 VIII The magic mirror of the workshop: painted and written references of potters and painters to themselves and their colleagues 145 Signatures and pictures of workshops are not the only direct references to themselves which Greek potters and pot-painters have left us.