Stories of the Spey Catchment (The Quotations from Gray Are Taken From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Guiding Badges and Insignia Brownie Six/Circle Emblems

Canadian Guiding Badges And Insignia Brownie Six/Circle Emblems Following the introduction of the Brownie program to provide Guiding for younger girls, and after the decision to base the new program on The Brownie Story, a further decision was made in 1919 to subdivide a Brownie Pack into smaller groups consisting of six girls. These smaller groups within the Pack were known as Sixes and were identified by a Six emblem bearing the name of some mythical fairy- like person from folklore. [Reference: POR (British, 1919)] The original Six emblems were brown felt; later versions were brown cotton with the edges bound in brown. In 1995, the term “Sixes” was replaced by the term “Circles”, and the shape of the emblems was changed as well. In 1972, three of the original twelve Six emblems were retired and in 1995 four new ones were added. Page 1 V.2 Canadian Guiding Badges And Insignia Brownie Six/Circle Emblems SC0001 SC0002 Bwbachod Badge Discontinued 1919- 19? 19? - 1972 SC0003 SC0004 Djinn Introduced 1994 1995-2004 1994 SC0005 SC0006 Dryad Introduced 1994 1995- 1994 Page 2 V.2 Canadian Guiding Badges And Insignia Brownie Six/Circle Emblems SC0007 SC0008 SC0009 Elf 1919-19? 19? - 1995 1995- SC0010 SC0011 SC0012 Fairy 1919-19? 19? - 1995 1995- SC0013 SC0014 Ghillie Dhu Badge Discontinued 1919-19? 19? - 1972 Page 3 V.2 Canadian Guiding Badges And Insignia Brownie Six/Circle Emblems SC0015 SC0016 SC0017 Gnome 1995- 1919-19? 19? - 1995 SC0018 SC0019 Imp Badge Discontinued 1919-19? 19? - 1995 SC0020 SC0021 SC0022 Kelpie (formerly called Scottish -

Elusive European Monsters Alli Starry

1 SELKIE Seal by sea and sheds its skin to walk on land in human form. This creature comes from the Irish and Scottish and Faroese folklore to keep their women cautious of men from the sea. 0 375 750 Km 9 KELPIE 2 PHOUKA N A shapeshifting water spirit in the lochs and A shapeshifting goblin sighted by the top of rivers of Scotland. The kelpie is told to warn the River Liffey. Takes drunkards on a wild children away from dangerous waters and women night ride and dumps them in random places. 6 to be wary of strangers. The Kelpie commonly Can be a nice excuse for a takes the shape of a horse with backwards hooves night at the pub. as it carries off its victims. 5 1 3 9 2 8 8 BOLOT N IK 4 A swamp monster originating from Poland. The Bolotnik pretends to be a stepping LOCH NESS 3 stone in a swamp when people pass through, then MON STER moves; causing its victims to fall into the mud where they can then be devoured. Legend has it that Loch Ness, Scotland has plesiosaur living in its depths. Affectionately named Nessie, a fisherman once 7 CET US spotted her surfacing the 7 Cetus is a sea monster from Greek Mythology. loch and Cetus is a mix between the sea serpent and a snapped a Map By: Alli Starry Monster information from Wikipedia whale. Its tale has been passed down through fuzzy picture. Pictures from deviantart.com the ages of Grecian folktales. It now resides World Mercator Projection; WKID: 54004 among the stars as a constellation. -

Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural

HORSE MOTIFS IN FOLK NARRATIVE OF THE SlPERNA TURAL by Victoria Harkavy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ___ ~C=:l!L~;;rtl....,19~~~'V'l rogram Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: ~U_c-ly-=-a2..!-.:t ;LC>=-----...!/~'fF_ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Victoria Harkavy Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland-College Park 2006 Director: Margaret Yocom, Professor Interdisciplinary Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful and supportive parents, Lorraine Messinger and Kenneth Harkavy. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Drs. Yocom, Fraser, and Rashkover, for putting in the time and effort to get this thesis finalized. Thanks also to my friends and colleagues who let me run ideas by them. Special thanks to Margaret Christoph for lending her copy editing expertise. Endless gratitude goes to my family taking care of me when I was focused on writing. Thanks also go to William, Folklore Horse, for all of the inspiration, and to Gumbie, Folklore Cat, for only sometimes sitting on the keyboard. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Interdisciplinary Elements of this Study ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

The Adorabyssal Oracle

THE ADORABYSSAL ORACLE The Adorabyssal Oracle is an oracle deck featuring the cutest versions of mythological, supernatural, and cryptozoological creatures from around the world! Thirty-six spooky cuties come with associated elements and themes to help bring some introspection to your day-to-day divinations and meditations. If you’re looking for something a bit more playful, The Adorabyssal Oracle deck doubles as a card game featuring those same cute and spooky creatures. It is meant for 2-4 players and games typically take 5-10 minutes. If you’re interested mainly in the card game rules, you can skip past the next couple of sections. However you choose to use your Adorabyssal Deck, it is my hope that these darkly delightful creatures will bring some fun to your day! WHAT IS AN ORACLE DECK? An Oracle deck is similar to, but different from, a Tarot deck. Where a Tarot deck has specific symbolism, number of cards, and a distinct way of interpreting card meanings, Oracle decks are a bit more free-form and their structures are dependent on their creators. The Adorabyssal Oracle, like many oracle decks, provides general themes accompanying the artwork. The basic and most prominent structure for this deck is the grouping of cards based on elemental associations. My hope is that this deck can provide a simple way to read for new readers and grow in complexity from there. My previous Tarot decks have seen very specific interpretation and symbolism. This Oracle deck opens things up a bit. It can be used for more general or free-form readings, and it makes a delightful addition to your existing decks. -

Heroes, Gods and Monsters of Celtic Mythology Ebook

HEROES, GODS AND MONSTERS OF CELTIC MYTHOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Fiona Macdonald,Eoin Coveney | 192 pages | 01 May 2009 | SALARIYA BOOK COMPANY LTD | 9781905638970 | English | Brighton, United Kingdom Heroes, Gods and Monsters of Celtic Mythology PDF Book This book is not yet featured on Listopia. The pursuit was a long one, and Caorthannach knew St. Danu DAH-noo. Details if other :. Co Kerry icon Fungie the Dolphin spotted after fears he was dead. The pair is said to whip the horses with a human spinal cord. Though the saint was desperately thirsty, he refused to drink from the poisoned wells and prayed for guidance. Scota SKO-tah. Showing The Dullahan rides a headless black horse with flaming eyes, carrying his head under one arm. He is said to have invented the early Irish alphabet called Ogham. Patrick when he banished the snakes out of Ireland. Cancel Reply. One monster, however, managed to escape — Caorthannach, the fire-spitter. Comments Show Comments. Carman is the Celtic goddess of evil magic. Leanan Sidhe would then take her dead lovers back to her lair. Ancient site of Irish Kings and the Tuatha de Danann. Now the Fomori have returned to their waters and transformed into sea monsters who prey on humans. Bay KIL-a. Patrick would need water to quench his thirst along the way, so she spitfire as she fled, and poisoned every well she passed. Several of the digital paintings or renderings for each of the archetypes expressed by various artists. According to Irish folklore, Sluagh are dead sinners that come back as malicious spirits. -

The Scottish Highlands Challenge

The Scottish Highlands Challenge “Wherever I wander, wherever I rove, The hills of the Highlands for ever I love” Robert Burns We created this challenge in 2015 to support one of our leaders to attend the GOLD (Guiding overseas linked with development) Ghana trip - we wanted to create something packed full of all the wee delights from the Scottish Highlands to introduce you to this beautiful part of the country, our traditions and the activities our units love. The challenge has been an overwhelming success & we are so proud of our Wee Scottish Coo! We have had to hibernate her for a small while but are super excited to be bringing the new updated challenge back for 2020! This challenge is all about traditions, adventurous activities, yummy food, local wildlife & th th mythical creatures! The challenge is ideal for Burns Night (25 J anuary) or St Andrews Day (30 November) - but can be done any time of the year! It also makes a great theme for overnights or camps - particularly if you want to come visit our lovely area! We have tried to give a range of activities, which should suit different age groups & abilities – a lot of the ideas are adaptable for whichever section you are working with. Rainbows 4+ activities Brownies 5+ activities Guides 6+ activities Rangers & Adults 8+ activities Please note: We have marked the ideas with these symbols ❈❈❈❈❈ to show which sections they may be most suitable for (but you know your unit best!) . Although older sections may want to read this pack & choose ideas, it is designed for Leaders to read. -

Fairy Tales; Their Origin and Meaning

Fairy Tales; Their Origin and Meaning John Thackray Bunce The Project Gutenberg EBook of Fairy Tales; Their Origin and Meaning by John Thackray Bunce Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Fairy Tales; Their Origin and Meaning Author: John Thackray Bunce Release Date: June, 2005 [EBook #8226] [This file was first posted on July 3, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: iso-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, FAIRY TALES; THEIR ORIGIN AND MEANING *** E-text prepared by David Deley FAIRY TALES, THEIR ORIGIN AND MEANING With Some Account of Dwellers in Fairyland BY JOHN THACKRAY BUNCE INTRODUCTORY NOTE. The substance of this volume was delivered as a course of Christmas Holiday Lectures, in 1877, at the Birmingham and Midland Institute, of which the author was then the senior Vice-president. -

Light and Dark

Light and dark The Mortal Realm is lit by two celestial bodies, the sun by day and the moon by night, but the same is not true of all realms. Some have neither and exist in total darkness, but most have some form of illumination. In the folklore of the Tuatha there are two kinds of Folk, those who walk in the daylight, the Seelie, and those who haunt the darkness, the Unseelie. To them the Seelie are kindly and helpful whilst the Unseelie are malicious and treacherous. This is a false distinction which was spread by the Fae during their rise in the mortal world. In truth, there is no moral distinction between diurnal and nocturnal Folk it is simply a matter of comfort. Some prefer gentle starlight, some like the heat of the day in midsummer, some need the cold to regulate their body temperature or are unable to tolerate sunlight on their skin. The terms Seelie and Unseelie really refer to their attitude towards the Fae. Those Folk who were happy, or at least not rebellious in their servitude to the Fae were extolled as ‘good’ or Seelie. Those who sought to break free from their slavery or turned against their masters were demonised as Unseelie. Folk branded Unseelie were often hunted down and made examples of, so they frequently took to venturing out of hiding only at night. The Fae are mostly daylight Folk although the stars are important to their dances. Certainly the Fae would not go abroad on pitch black, starless nights and so the renegade Folk would be safe to travel abroad under the cloak of night. -

Folklore Creatures BANSHEE: Scotland and Ireland

Folklore creatures BANSHEE: Scotland and ireland • Known as CAOINEAG (wailing woman) • Foretells DEATH, known as messenger from Otherworld • Begins to wail if someone is about to die • In Scottish Gaelic mythology, she is known as the bean sìth or bean-nighe and is seen washing the bloodstained clothes or armor of those who are about to die BANSHEE Doppelganger: GERMANY • Look-alike or double of a living person • Omen of bad luck to come Doppelganger Goblin: France • An evil or mischievous creature, often depicted in a grotesque manner • Known to be playful, but also evil and their tricks could seriously harm people • Greedy and love money and wealth Goblin Black Dog: British Isles • A nocturnal apparition, often said to be associated with the Devil or a Hellhound, regarded as a portent of death, found in deserted roads • It is generally supposed to be larger than a normal dog, and often has large, glowing eyes, moves in silence • Causes despair to those who see it… Black Dog Sea Witch: Great Britain • Phantom or ghost of the dead • Has supernatural powers to control fate of men and their ships at sea (likes to dash ships upon the rocks) The Lay Of The Sea Witch In the waters darkness hides Sea Witch Beneath sky and sun and golden tides In the cold water it abides Above, below, and on all sides In the Shadows she lives Without love or life to give Her heart is withered, black, dried And in the blackness she forever hides Her hair is dark, her skin is silver At her dangerous beauty men shiver But her tongue is sharp as a sliver And at -

On the Trail of Scotlands Myths and Legends Free

FREE ON THE TRAIL OF SCOTLANDS MYTHS AND LEGENDS PDF Stuart McHardy | 152 pages | 01 Apr 2005 | LUATH PRESS LTD | 9781842820490 | English | Edinburgh, United Kingdom Myths and legends play a major role in Scotland's culture and history. From before the dawn of history, the early ancestors of the people we now know as the Scots, built impressive monuments which have caught the imagination of those who have followed in their wake. Stone circles, chambered cairns, brochs and vitrified forts stir within us something primeval and stories have been born from their mystical qualities. Scottish myths and legends have drawn their inspiration from many sources. Every land has its tales of dragons, but Scotland is an island country, bound to the sea. Cierein Croin, a gigantic sea serpent is said to be the largest creature ever. Yes, Nessie is classified as a dragon although she may be a member of that legendary species, the each-uisge or water horse. However, the cryptozoologists will swear that she is a leftover plesiosaurus. The Dalriadan Scots shared more than the Gaelic tongue with their trading partners in Ireland. They were great storytellers and had a culture rich in tales of heroes and mythical creatures. Many of the similarities between Irish and Scottish folklore can be accounted for by their common Celtic roots. Tales of Finn On the Trail of Scotlands Myths and Legends Cumhall and his warrior band, the Fianna are as commonplace on the Hebrides as in Ireland. Many of the myths centre around the cycle of nature and the passing of the seasons with the battle between light and darkness, summer and winter. -

Ushig (Annemarie Allan)

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO USHIG by Annemarie Allan www.florisbooks.co.uk Themes/issues addressed in this book Kelpies Series Summary Family, friendship, trust, betrayal, Scottish folklore, kelpies, selkies, responsibility, The award-winning Kelpies series is danger Scotland’s favourite collection of children’s fiction. Floris Books took Book Summary over the list in 2001, republishing On holiday in Scotland, Ellen and Davie attempt to help a stray pony back to safety, but classic works by authors such as to their horror it turns into a huge, black kelpie and attempts to overpower them. Ellen Kathleen Fidler, Mollie Hunter, George manages to fight against it and they seem to repel its power. However, the kelpie shifts Mackay Brown and Allan Campbell shape and follows them back home to London in the guise of a boy named Ushig, and McLean. Since then, we have continued it is clear that he has ‘glamoured’ Davie. When Ushig takes Davie away to an alternate to add to the series with a range of Aldhammer, where the Queen of the Night rules, Ellen manages to follow and attempts highly successful new Scottish novels to free Davie from the power Ushig has over him. Ushig is bewildered by the lengths for children including books by Ellen will go to to save her brother, and when he betrays the pair to the Wild Hunt, it Gill Arbuthnott, Alex Nye, Lari Don, seems that all is lost. However, Ellen and Davie discover they have selkie blood in them Anne Forbes, Annemarie Allan, and their selkie relatives come to their aid. -

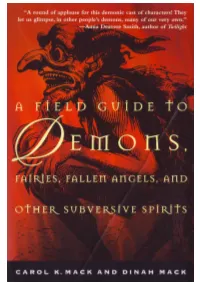

A-Field-Guide-To-Demons-By-Carol-K

A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS CAROL K. MACK AND DINAH MACK AN OWL BOOK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Owl Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com An Owl Book® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 1998 by Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress-in-Publication Data Mack, Carol K. A field guide to demons, fairies, fallen angels, and other subversive spirits / Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack—1st Owl books ed. p. cm. "An Owl book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-6270-0 ISBN-10: 0-8050-6270-X 1. Demonology. 2. Fairies. I. Mack, Dinah. II. Title. BF1531.M26 1998 99-20481 133.4'2—dc21 CIP Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First published in hardcover in 1998 by Arcade Publishing, Inc., New York First Owl Books Edition 1999 Designed by Sean McDonald Printed in the United States of America 13 15 17 18 16 14 This book is dedicated to Eliza, may she always be surrounded by love, joy and compassion, the demon vanquishers. Willingly I too say, Hail! to the unknown awful powers which transcend the ken of the understanding. And the attraction which this topic has had for me and which induces me to unfold its parts before you is precisely because I think the numberless forms in which this superstition has reappeared in every time and in every people indicates the inextinguish- ableness of wonder in man; betrays his conviction that behind all your explanations is a vast and potent and living Nature, inexhaustible and sublime, which you cannot explain.