View the Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CATALOG Mayan Stelaes

CATALOG Mayan Stelaes Palos Mayan Collection 1 Table of Contents Aguateca 4 Ceibal 13 Dos Pilas 20 El Baúl 23 Itsimite 27 Ixlu 29 Ixtutz 31 Jimbal 33 Kaminaljuyu 35 La Amelia 37 Piedras Negras 39 Polol 41 Quirigia 43 Tikal 45 Yaxha 56 Mayan Fragments 58 Rubbings 62 Small Sculptures 65 2 About Palos Mayan Collection The Palos Mayan Collection includes 90 reproductions of pre-Columbian stone carvings originally created by the Mayan and Pipil people traced back to 879 A.D. The Palos Mayan Collection sculptures are created by master sculptor Manuel Palos from scholar Joan W. Patten’s casts and rubbings of the original artifacts in Guatemala. Patten received official permission from the Guatemalan government to create casts and rubbings of original Mayan carvings and bequeathed her replicas to collaborator Manuel Palos. Some of the originals stelae were later stolen or destroyed, leaving Patten’s castings and rubbings as their only remaining record. These fine art-quality Maya Stelae reproductions are available for purchase by museums, universities, and private collectors through Palos Studio. You are invited to book a virtual tour or an in- person tour through [email protected] 3 Aguateca Aguateca is in the southwestern part of the Department of the Peten, Guatemala, about 15 kilometers south of the village of Sayaxche, on a ridge on the western side of Late Petexbatun. AGUATECA STELA 1 (50”x85”) A.D. 741 - Late Classic Presumed to be a ruler of Aguatecas, his head is turned in an expression of innate authority, personifying the rank implied by the symbols adorning his costume. -

Chapter 5 Nawat

Chapter 5 Nawat 5.1 Introduction This chapter introduces the Nawat/Pipil language. Section 5.2 explains the Nawat/Pipil and the Nawat/Nahuatl distinction. A brief history of the Pipil people is provided in section 5.3. Section 5.4 reviews the available Nawat language resources. A basic grammar is outlined in section 5.5. A more complete description would require more resources beyond the scope of the present project. Section 5.6 discusses the issues that arise for the present project, including what alphabet and dialect to use. Section 5.7 provides a summary of the chapter. 5.2 Nawat – Some Basic Facts Nawat versus Pipil In the literature, the Nawat language of El Salvador is referred to as Pipil. The people who speak the language are known as the Pipil people, hence the use of the word Pipil for their language. However, the Pipil speakers themselves refer to their language as Nawat. In El Salvador, the local Spanish speakers refer to the language as “nahuat” (pronounced “/nawat/”). Throughout this document, the language will be called Nawat. El Salvador is a small country in Central America. It is bordered on the north-west by Guatemala and on the north-east by Honduras. See Figure 5.1 for a map of Central America. El Salvador (Used by permission of The General Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin) Figure 5.1 Map of Central America 75 Nawat versus Nahuatl Nawat is an Uto-Aztecan language (Campbell, 1985). It is related to the Nahuatl language spoken in Mexico (which is where the Pipils originally came from, see section 5.3). -

The Talcigüines of El Salvador

The Talcigüines of El Salvador: A Contextual Example of Nahua Drama in the Public Square Robert A. Danielson, Ph.D. Asbury Theological Seminary DOI: 10.7252/Paper. 0000 22 | The Talcigüines of El Salvador: ABSTRACT: Anthropologist Louise M. Burkhart has spent decades studying the literary dramas of the Nahua speakers of 16th and 17th century Colonial Mexico. While many of these dramas illustrate the blending of Christianity with pre- Christian indigenous religion in Latin America, they have seldom been studied as early examples of contextualized Christianity or syncretism within early Spanish missions in Latin America. Tese early Nahua dramas became elaborate performances that expressed indigenous understandings of Christian stories and theology. Burkhart notes that Spanish priests controlled Nahua drama through reviewing and approving the scripts, but also by keeping the performances out of the church buildings. Tis approach did not stop these contextualized dramas, but rather integrated them into traditional religious performances acted out in public spaces. While many of these dramas exist now only as ancient scripts or recorded accounts, some modern remnants may still exist. One possibility is the Talcigüines of Texistepeque, El Salvador. Performed every Monday of Holy Week, this festival continues to combine Christian themes with indigenous symbols, moving from within the church to the literal public square. Developed for the Nahua speaking Pipil people of one of the oldest colonial parishes in El Salvador, this drama contains many of Burkhart’s elements. Robert A. Danielson, Ph.D. | 23 INTRODUCTION On the Monday of Holy Week each year, a unique performance occurs in the small town of Texistepeque, in the western region of El Salvador in Central America. -

Quoted, 264 Adelman, Je

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-13328-9 - Colonialism and Postcolonial Development: Spanish America in Comparative Perspective James Mahoney Index More information Index Abad people, 106 to Canada, 251; and contrasting Abernethy, David B., 2 levels of development in interior vs. Aborigines, 236 littoral, 132; and estancias, 127–8, Acemoglu, Daron, 13–14, 17–19, 234, 146; European migration to, 131, 264–5; quoted, 264 211; and exploitation of indigenous Adelman, Jeremy, 204; quoted, 203 population, 81; exports of, 128; Africa: British colonialism in, 236–7; financial institutions in, 126;and economic and social disaster in, 237, “free trade,” 125–6; gaucho workers 257; precolonial societies, 256 in, 127; GDP per capita of, 128, African population: as cause of liberal 210–12; “golden age” in, 128, 210, colonialism, 183, 201; in colonial 211; intendant system in, 126; Argentina, 125–6, 130; in colonial investments in education in, 224;lack Brazil, 245–6; in colonial Colombia, of dominance of large estates in, 127; 107–8, 160; in colonial El Salvador, landed class of, 127; literacy and life 95; colonial exploitation of, 53;in expectancy in, 222–4; livestock colonial Mexico, 58, 60; in colonial industry of, 82, 126–7, 130, 211; Peru, 67–9, 71; in colonial Uruguay, merchants in, 82, 126–8; 80; in United States, 236;inWest nation-building myths in, 224; Indies, precolonial societies in, 77–9; 238; see also slavery problems of industrialization in, 211, Alvarado, Pedro de, 94, 97 212; reversal of development in, 212; Amaral, Samuel, quoted, -

Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1952 Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times John L. Sorenson Sr. Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sorenson, John L. Sr., "Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times" (1952). Theses and Dissertations. 5131. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5131 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. e13 ci j rc171 EVIDENCES OPOFCULTURE CONTACTS BETWEEN POLIIESIAPOLYNESIA AND tiletlleTIIETHE AMERICAS IN preccluivibianPREC olto4bian TIMES A thesthesisis presented tobo the department of archaeology brbrighamighambigham Yyoungoung universityunivervens 1 ty provo utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts n v rb hajbaj&aj by john leon sorenson july 1921952 ACmtodledgiventsackiiowledgments thanks are proffered to dr M wells jakenjakemjakemanan and dr sidney B sperry for helpful corencoxencommentsts and suggestions which aided research for this thesis to the authors wife kathryn richards sorenson goes gratitude for patient forbearance constant encouragement -

The Indicenous Presence in Rubén D a ~ O and Ernesto

THE INDICENOUS PRESENCE IN RUBÉN DA~OAND ERNESTO CARDENAL John Andrew Morrow A thesis submitted in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Spanish and Portuguese University of Toronto O Copyright by John A. Morrow, 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of,,, du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rwWellington OltawaON KlAW OMwaON KlAW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence aiiowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. .. 11 ABSTRACT The Indigenous Presence in Rubén Dario and Emesto Cardenal. Morrow, John A., Ph-D. University of Toronto, 2000.346pp. Director: Keith Ellis. This dissertation examines the indigenous presence in the poetry of Rubén Dario and Emesto Cardenal. It is divided into two sections, the fkst dealing with Dario and the second with Cardenal. In both sections the literary analysis is preceeded by a critical contextuaiization. -

An Overview of El Salvador

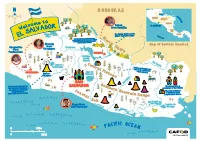

An Overview of El Salvador History The Olmecs came to the region in 2000 B.C., followed by the Maya in 1500 B.C. When the Maya civilization ended in 900 A.D., the Toltec Empire took hold in El Salvador. In the 11th century, the Pipil people became the dominant group in El Salvador until the Spanish conquerors landed. The Pipil Indians, descendants of the Aztecs, likely migrated to the region in the 11th century. In 1528, Pedro de Alvarado, a Spanish lieutenant of Cortés, took over El Salvador and forced the native people to become servants. The forced intermixing and intermarriage by Spanish men with the Native American Indigenous Lenca and Pipil women happened almost immediately after the arrival of the European Spanish. The majority of Salvadorans in El Salvador identify themselves as 87% mestizo, leaving 12% white and ~1% indigenous Salvadoran population as a minority. El Salvador, with the other countries of Central America, declared its independence from Spain on Sept. 15, 1821, and was part of a federation of Central American states until that union dissolved in 1838. For decades after its full independence in 1841, El Salvador experienced numerous revolutions and wars against other Central American republics. From 1931 to 1979 El Salvador was ruled by a series of military dictatorships. GCYL An Overview of El Salvador 1 Salvadorans who are racially European, especially Mediterranean, as well as tri-racial Pardo Salvadorans and indigenous people in El Salvador who do not speak indigenous languages nor have an indigenous culture, also identify themselves as Mestizo culturally. -

El Salvador Information and Lesson Activity Sheets (Pdf, 3Mb)

# !"#$%&'( G563Z5 'F 8 5 6' # C%'F5E'6' F !"#$%&'( 3) 0" ) 5 ' # ( *0,: #3)'&'C%' :; 00000X.-*+ 560('67'$"& /9 & I-:;0C2.-D</. * & <: " 0 $ ( )"(F' 8 ' 2 67 ; &3)' ' = ( 2 FH*0(<*--.0E.?-*0;*.+B 1'#'E' 0 6.>:0?* / 1 6 E:,H*-0E:2+,.<+0&.+>*O0 ') C2<D. 34 3)0" 5 ( )5' # 5/0(./J.?:-0H.B0.0,-:=<9./09/<;.,*U0 < N<,H0,N:0B*.B:+BO0FH*0?-L0B*.B:+0<B0I-:;0 * #:J*;A*-0,:0'=-</0.+?0,H*0N*,0B*.B:+0 - <B0I-:;0E.L0,:0"9,:A*-O0 -. '-.9*/L 0 E.=0:I0)*+,-./0';*-<9. I-:; E K.9@2*/<+* &<:06*;=. ).9H.>2. ? I-:; -* 12*+,*9<,:B GUARJILA 5;A./B* )*--:+ C-.+?* &< :0F )*+,-./01/.,*.2 :- 00006.>:0?* :/. ):.,*=*@2* ):II**0.+?0B2>.-0.-*0 ,N:0:I05/0(./J.?:-RB0 ;.<+0*S=:-,BO GUAYMANGO 6.>:0?* 3Y./9: 3/:=.+>: 7:/9.+: =. ; * 06 SAN <: ( & 5/0(./J.?:-0<B0M+:N+0.B0 SALVADOR :2 5/0(./J.?:-0H.B0. , =:=2/.,<:+0:I0TOP0;<//<:+O ,H*06.+?0:I07:/9.+:*BO0 H* 00 FH*0B:2,H*-+0;:2+,.<+0 - + FH*0;.<+0/.+>2.>* -.+>*0<+9/2?*B0 ) 0E : :2 <B0(=.+<BHO0(:;* ;:-*0,H.+0PQ0J:/9.+:*BO0 . + B ,.< =*:=/*0B=*.M0#.H2.O ,. +0&.+>*0 / 00 G*/ , &<:0C-.+?*0?* 00000$<*>:0I-:;0000000 (.+0E<>2*/ 6.>2+.0?* (.+0(./J.?:- "/:;*>. ')343)0")5' Q VQM; 1 # Q WQ;< EL SalvAdOR infORmAtiOn sHEEt Geography Location faith and culture El Salvador is on the western coast of Central America. Guatemala is to The majority of people in El Salvador are Roman Catholic. -

Chapter 3 Second Land of Nephi

MORMON FOOTPRINT IN MESOAMERICA BY ROBERT A. PATE PH.D. To my father, Alma Jacob Pate, who loved the Scriptures and taught us where blessings come from. To my mother, a most loyal lady to her husband and family. To my wife Elaine who made President Ezra Taft Benson’s admonition to study the Book of Mormon a beloved reality in our home. To our children who responded to the Prophets’ admonitions. To the great prophet historian Mormon and his faithful son Moroni for their history and witness of Jesus Christ. And, to the beloved Prophet Joseph Smith and the day when men will know his history. MORMON FOOTPRINT IN MESOAMERICA COPYRIGHT © 2012 ROBERT A. PATE All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photographic, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. First Printing: February 2012 Printed in the United States of America ISBN-10: 0985151919 ISBN-13: 978-0-9851519-1-1 Cover design by Adam R. Hopkins Published by the Alma Jacob Pate Family 2222 West 600 South Logan, Utah 84321 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Mormon’s Footprint in Mesoamerica is a continuation of discovery that follows publication of Mapping the Book of Mormon: A Comprehensive Geography of Nephite America; Mormon Names in Maya Stone; and Mormon Key to Maya Code. The ten years since the first publication have brought many more discoveries which provide additional confirmation of most of the findings and bring into better focus areas that needed correction. -

Hellbound in El Salvador: Heavy Metal As a Philosophy of Life in Central America

HELLBOUND IN EL SALVADOR: HEAVY METAL AS A PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE IN CENTRAL AMERICA by Christian Pack A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2018 © 2018 Christian Pack All Rights Reserved Abstract Heavy Metal in El Salvador has been a driving force of the underground culture since the Civil War in the 1980s. Over time, it has grown into a large movement that encompasses musicians, producers, promoters, media outlets and the international exchange of music, ideas and live shows. As a music based around discontent with society at large, Heavy Metal attempts to question the status quo through an intellectual exploration of taboo subjects and the presentation of controversial live shows. As an international discourse, Heavy Metal speaks to ideas of both socio-political and individual power based around a Philosophy of Life that exalts personal freedoms and personal responsibility to oneself and their society. As a community, it represents a ‘rage’ group, as defined by Peter Sloterdijk, that questions Western epistemologies and the doctrines of Christian Philosophy. This is done in different ways, by different genres, but at the heart is the changing of macro- (international) discourses into micro- (local) discourses that focus on those issues important to the geographic specificity of the region. In the case of Black Metal, born in Norway, it is interpreted in El Salvador through the similarities between the doctrines of Hitler and those of the most famous dictator in the country’s history – General Maximiliano Hernandez – and then applied, ironically, to the local phenomena of the Salvadoran Street Gangs (MS-13 and 18s) and their desired extermination. -

Considerations for Expanding the Utilization Of

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DEVELOPING A SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE RESEARCH AND EDUCATION CENTRE AT AGUA BLANCA, EL SALVADOR By BRADLEY JEFFERSON SMITH B.Sc., Royal Roads University, 2005 Diploma of Environmental Technology, Camosun College, 1998 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: MASTER OF ARTS In ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ……………………………… Dr. Lenore Newman, MEM Program Head School of Environment and Sustainability ……………………………… Dr. Lenore Newman, Academic Thesis Supervisor School of Environment and Sustainability …………………………… Dr. Tony Boydell, Director School of Environment and Sustainability ROYAL ROADS UNIVERSITY April 2009 © Bradley Jefferson Smith, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-71942-8 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-71942-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. -

The Resilience of Indigenous Culture in El Salvador

University of Maryland, College Park The Resilience of Indigenous Culture in El Salvador Ashley A. Escobar LASC Capstone Thesis Dr. Britta Anderson December 6th 2018 Introduction and Personal History In the spirit of research, I recently took a 23 and Me ancestry DNA test and the results gave me much to consider about my own roots. Given the historical framework of conquest and patterns of migrations across the Americas, I expected some of these results as the daughter of Salvadoran immigrants: 52% Native American with ancestors from El Salvador, 33% European with ancestors from Spain, 7% Sub Saharan African with Senegambian, Guinean, and Congolese ancestry, and 6% of my heritage being broadly traced to various, far-flung regions of the globe. The prominence of indigenous ancestry that was picked up in my DNA was evidence to me of the resilience of indigenous ancestors who were silenced through years of hegemonic rule—and that we are still here. The indigenous people of El Salvador are still alive despite the notion that we have long been wiped out; either by force or by choice we have instead taken on cultural attitudes that have masked our roots in order to survive violent oppression. History is typically written by the victors and silences the voices of those they vanquish, which is reflected in the lack of documentation and archival records of indigenous groups in El Salvador, as well as the sheer difficulty of obtaining many officiated documents. Despite this, there are subtle ways indigenous culture has been kept alive in popular Salvadoran culture: our traditional foods, our vernacular, and celebrations all weave together vestiges of a culture that could not be vanquished.