The History of the Ursulines and Their Schools in Lower Silesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oder-Neisse Line As Poland's Western Border

Piotr Eberhardt Piotr Eberhardt 2015 88 1 77 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/ GPol.0007 April 2014 September 2014 Geographia Polonica 2015, Volume 88, Issue 1, pp. 77-105 http://dx.doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0007 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE ODER-NEISSE LINE AS POLAND’S WESTERN BORDER: AS POSTULATED AND MADE A REALITY Piotr Eberhardt Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization Polish Academy of Sciences Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warsaw: Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the historical and political conditioning leading to the establishment of the contemporary Polish-German border along the ‘Oder-Neisse Line’ (formed by the rivers known in Poland as the Odra and Nysa Łużycka). It is recalled how – at the moment a Polish state first came into being in the 10th century – its western border also followed a course more or less coinciding with these same two rivers. In subsequent cen- turies, the political limits of the Polish and German spheres of influence shifted markedly to the east. However, as a result of the drastic reverse suffered by Nazi Germany, the western border of Poland was re-set at the Oder-Neisse Line. Consideration is given to both the causes and consequences of this far-reaching geopolitical decision taken at the Potsdam Conference by the victorious Three Powers of the USSR, UK and USA. Key words Oder-Neisse Line • western border of Poland • Potsdam Conference • international boundaries Introduction districts – one for each successor – brought the loss, at first periodically and then irrevo- At the end of the 10th century, the Western cably, of the whole of Silesia and of Western border of Poland coincided approximately Pomerania. -

Transformation of the Identity of a Region: Theory and the Empirical Case of the Perceptual Regions of Bohemia and Moravia, Czech Republic

MORAVIAN GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS 2020, 28(3):2020, 154–169 28(3) MORAVIAN MORAVIAN GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS Fig. 3. Members of the International Advisory Board of the Fig. 4. The Löw-Beer Villa in Brno, a place of the award MGR journal in front of the Institute of Geonics ceremony The Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geonics journal homepage: http://www.geonika.cz/mgr.html Fig. 5. Professor Eva Zažímalová, president of the Czech Fig. 6. Professor Bryn Greer-Wootten has his speech during Academy of Sciences, presents Professor Bryn Greer-Wootten the award ceremony doi: https://doi.org/10.2478/mgr-2020-0012 with the honorary medal Illustrations related to the paper by R. Blaheta et al. (photo: T. Krejčí, E. Nováková (2×), Z. Říha) Transformation of the identity of a region: Theory and the empirical case of the perceptual regions of Bohemia and Moravia, Czech Republic Petr MAREK a * Abstract By using the concept of perceptual region – an essential part of the identity of a region and a part of every person’s mental map – this paper demonstrates a way to examine the understudied transformation of (the identity of) a region and, specifically, its territorial shape (boundaries). This concept effectively fuses the “institutionalisation of regions” theory and the methodologies of behavioural geography. This case study of the perceptual regions of Bohemia and Moravia shows how and why these historical regions and their boundary/boundaries developed, after a significant deinstitutionalisation by splitting into smaller regions in an administrative reform. Many people now perceive the Bohemian-Moravian boundary according to the newly-emerged regional boundaries, which often ignore old (historical) boundaries. -

Logistics of Czech Business at Time of Economic Recession

SO FAR , SO GOOD OLOMOUC REGION US SUCCESS OF CZECH SCIENTISTS’ INVENTION PARALYMPICS WINNER AND WORLD CYCLING CHAMPION JIŘÍ JEŽEK LOGISTICS OF CZECH BUSINESS AT TIME OF ECONOMIC RECESSION THE CZECH REPUBLIC PRESIDING OVER THE 11-12 COUNCIL OF THE EU IN THE FIRST HALF OF 2009 2009 MASARYK UNIVERSITY (MU) RANKS AMONG THE EDUCATIONAL AND RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS IN EUROPE WHICH ARE DEVELOPING MOST RAPIDLY. IT IS GRADUALLY BECOMING A CENTRE OF EURO- PEAN RESEARCH, ESPECIALLY IN THE INTER-BRANCH FIELDS OF LIFE SCIENCE, INFORMATICS, AND SOCIAL SCIENCE. IN THE STAGE OF PREPARATIONS ARE CENTRES OF EXCEL- LENT SCIENCE SUCH AS THE AMBITIOUS PROJECT OF THE CENTRAL EUROPEAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (CEITEC, WWW.CEITEC.EU), WHICH IS FOCUSED ON BASIC RESEARCH, AS WELL AS IMPORTANT REGIONAL CENTRES OF APPLIED RE- SEARCH (INCLUDING CETOCOEN AND CERIT). A boost to the dynamic development of MU was given by the unique project of a university campus built on an area of 20 hectares in Brno-Bohunice at the cost of approximately EUR 200 million between 2005 and 2009. It is comprised of two dozen pavilions for Life Science and includes an incuba- Architecture and general designer A PLUS a.s.; Photo for a.s. by Zdeněk Náplava tor of biomedical technologies for newly established fi rms. The MU place of contact for co-operation with partners is the Technology Transfer Offi ce, which protects the MU intellec- tual property and secures the transfer of technologies and knowledge. More information is available at www.muni.cz, www.ctt.muni.cz (direct contact: Jan Slovák, Director of the MU Technology Transfer Offi ce, [email protected]). -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

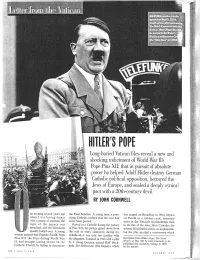

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Breslau Or Wrocław? the Identity of the City in Regards to the World War II in an Autobiographical Reflection

DEBATER A EUROPA Periódico do CIEDA e do CEIS20 , em parceria com GPE e a RCE. N.13 julho/dezembro 2015 – Semestral ISSN 1647-6336 Disponível em: http://www.europe-direct-aveiro.aeva.eu/debatereuropa/ Breslau or Wrocław? The identity of the city in regards to the World War II in an autobiographical reflection Anna Olchówka University of Wrocław E-mail: [email protected] Abstract On the 1st September 1939 a German city Breslau was found 40 kilometers from the border with Poland and the first front lines. Nearly six years later, controlled by the Soviets, the city came under the "Polish administration" in the "Recovered Territories". The new authorities from the beginning virtually denied all the past of the city, began the exchange of population and the gradual erasure of multicultural memory; the heritage of the past recovery continues today. The main objective of this paper is to present the complexity of history through episodes of a city history. The analysis of texts and images, biographies of the inhabitants / immigrants / exiles of Breslau / Wrocław and the results of modern research facilitate the creation of a complex political, economic, social and cultural landscape, rewritten by historical events and resettlement actions. Keywords: Wrocław; Breslau; identity; biography; history Scientific meetings and conferences open academics to new perspectives and face them against different opinions, arguments, works and experiences. The last category, due to its personal and individual aspect, is very special. Experience can be shared and gained at the same time, which is inherent to the continuous development of human beings. Because of its subjectivity, experiences often pose a great methodological problem for the humanistic studies. -

The Historical Cultural Landscape of the Western Sudetes. an Introduction to the Research

Summary The historical cultural landscape of the western Sudetes. An introduction to the research I. Introduction The authors of the book attempted to describe the cultural landscape created over the course of several hundred years in the specific mountain and foothills conditions in the southwest of Lower Silesia in Poland. The pressure of environmental features had an overwhelming effect on the nature of settlements. In conditions of the widespread predominance of the agrarian economy over other categories of production, the foot- hills and mountains were settled later and less intensively than those well-suited for lowland agriculture. This tendency is confirmed by the relatively rare settlement of the Sudetes in the early Middle Ages. The planned colonisation, conducted in Silesia in the 13th century, did not have such an intensive course in mountainous areas as in the lowland zone. The western part of Lower Silesia and the neighbouring areas of Lusatia were colonised by in a planned programme, bringing settlers from the German lan- guage area and using German legal models. The success of this programme is consid- ered one of the significant economic and organisational achievements of Prince Henry I the Bearded. The testimony to the implementation of his plan was the creation of the foundations of mining and the first locations in Silesia of the cities of Złotoryja (probably 1211) and Lwówek (1217), perhaps also Wleń (1214?). The mountain areas further south remained outside the zone of intensive colonisation. This was undertak- en several dozen years later, at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, and mainly in the 14th century, adapting settlement and economy to the special conditions of the natural environment. -

Program Ochrony Środowiska Dla Powiatu Średzkiego

Zleceniodawca: Starostwo Powiatowe w Środzie Śląskiej ul. Wrocławska 2 55 – 300 Środa Śląska Temat: PROGRAM OCHRONY ŚRODOWISKA DLA POWIATU ŚREDZKIEGO Wykonawca: PPD WROTECH Sp. z o.o. ul. Australijska 64 B, 54-404 Wrocław tel. (0-71) 357-57-57, fax 357-76-36, e-mail: [email protected] Wrocław, czerwiec 2004 r. Program Ochrony Środowiska dla powiatu średzkiego Spis treści Spis tabel: ............................................................................................................................. 4 Spis wykresów: .................................................................................................................... 4 Spis rysunków: ..................................................................................................................... 5 1. WPROWADZENIE ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Podstawa formalno – prawna opracowania ............................................................ 6 1.2. Cel i zakres Programu Ochrony Środowiska .......................................................... 6 1.3. Korzyści wynikające z posiadania Programu Ochrony Środowiska ........................ 8 1.4. Metodyka opracowania Programu Ochrony Środowiska ........................................ 8 2. Ogólna charakterystyka powiatu ................................................................................. 9 2.1. Położenie i funkcje powiatu .................................................................................... 9 2.2. Warunki -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City Major Disturbance

In Breslau, the overthrow of the imperial authorities passed off without MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City major disturbance. On 8 November, a Loyal Appeal for the citizens to uphold by Norman Davies (pp. 326-379) their duties to the Kaiser was distributed in the names of the Lord Mayor, Paul Matting, Archbishop Bertram and others. But it had no great effect. The Commander of the VI Army Corps, General Pfeil, was in no mood for a fight. Breslau before and during the Second World War He released the political prisoners, ordered his men to leave their barracks, 1918-45 and, in the last order of the military administration, gave permission to the Social Democrats to hold a rally in the Jahrhunderthalle. The next afternoon, a The politics of interwar Germany passed through three distinct phases. In group of dissident airmen arrived from their base at Brieg (Brzeg). Their arrival 1918-20, anarchy spread far and wide in the wake of the collapse of the spurred the formation of 'soldiers' councils' (that is, Soviets) in several military German Empire. Between 1919 and 1933, the Weimar Republic re-established units and of a 100-strong Committee of Public Safety by the municipal leaders. stability, then lost it. And from 1933 onwards, Hitler's 'Third Reich' took an The Army Commander was greatly relieved to resign his powers. ever firmer hold. Events in Breslau, as in all German cities, reflected each of The Volksrat, or 'People's Council', was formed on 9 November 1918, from the phases in turn. Social Democrats, union leaders, Liberals and the Catholic Centre Party. -

Gmina Prudnik Położona Jest W Południowej Części Województwa Opolskiego, Graniczy Z Republiką Czeską

Prudnik miasto z wizją Położenie Gmina Prudnik położona jest w południowej części województwa opolskiego, graniczy z Republiką Czeską. Przez gminę prowadzi szlak komunikacyjny z północy Europy na jej południe. Prudnik jest bardzo dobrze skomunikowany poprzez siec dróg krajowych z autostradą A4 oraz z siecią dróg międzynarodowych między innymi Czech i Słowacji. Gminę zamieszkuje 27 500 mieszkańców, znanych ze swej pracowitości i uczciwości. Miasto dzięki swojemu położeniu jest „bramą” na południe Europy, miejscem z którego jest blisko do aglomeracji w Polsce oraz południa Europy. Największe miasta, porty lotnicze Litwa Białoruś BERLIN Niemcy LEGENDA inwestycje ukończone lub w trakcie realizacji nowe inwestycje ujęte w planie 2014-2023 nowe planowane inwestycje PRAGA PRUDNIK Czechy OSTRAVA Ukraina Słowacja . odległość z Prudnika . odległość z Prudnika . do większych miast . do największych portów lotniczych . Opole 50 km . Ostrawa 95 km Wrocław 115 km . Wrocław 115 km . Katowice 125 km . Katowice 125 km Kraków 200 km . Kraków 200 km Praga 280 km . Warszawa 380 km . Warszawa 380 km . Berlin 450 km . Oferta inwestycyjna Wałbrzyska Specjalna Strefa Ekonomiczna – Podstrefa Prudnik Tereny niezabudowane - ul.Przemysłowa 10 Tereny zabudowane - ul.Nyska 13469.85 m2 Pomoc dla inwestorów Prowadząc działalność gospodarczą na terenie Wałbrzyskiej Specjalnej Strefy Ekonomicznej, przedsiębiorca otrzymuje pomoc publiczną w postaci ulg podatkowych (zwolnienie z podatku dochodowego CIT lub PIT w zależności od formy prowadzenia działalności). WIELKOŚĆ WOJEWÓDZTWO WOJEWÓDZTWO LUBUSKIE DOLNOŚLĄSKIE FIRMY I OPOLSKIE I WIELKOPOLSKIE do do 35% 25% kosztów DUŻE inwestycji ulga w podatku lub do do dochodowym 2-letnich 45% 35% kosztów CIT ŚREDNIE zatrudnienia lub nowych do do PIT 55% 45% pracowników MAŁE I MIKRO źródło: https://invest-park.com.pl/dla-inwestora/ulgi-podatkowe-pomoc-publiczna/ Gmina Prudnik posiada program pomocy de minimis dla przedsiębiorców tworzących nowe miejsca pracy w związku z nową inwestycją. -

Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Sisterhood on the Frontier: Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850- 1925 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Jamila Jamison Sinlao Committee in charge: Professor Denise Bielby, Chair Professor Jon Cruz Professor Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi Professor John Mohr December 2018 The dissertation of Jamila Jamison Sinlao is approved. Jon Cruz Simonetta Falsca-Zamponi John Mohr Denise Bielby, Committee Chair December 2018 Sisterhood on the Frontier: Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850- 1925 Copyright © 2018 by Jamila Jamison Sinlao iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In so many ways, this dissertation is a labor of love, shaped by the formative years that I spent as a student at Mercy High School, Burlingame. There, the “Mercy spirit”—one of hospitality and generosity, resilience and faith—was illustrated by the many stories we heard about Catherine McAuley and Mary Baptist Russell. The questions that guide this project grew out of my Mercy experience, and so I would like to thank the many teachers, both lay and religious, who nurtured my interest in this fascinating slice of history. This project would not have been possible without the archivists who not only granted me the privilege to access their collections, but who inspired me with their passion, dedication, and deep historical knowledge. I am indebted to Chris Doan, former archivist for the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary; Sister Marilyn Gouailhardou, RSM, regional community archivist for the Sisters of Mercy Burlingame; Sister Margaret Ann Gainey, DC, archivist for the Daughters of Charity, Seton Provincialate; Kathy O’Connor, archivist for the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, California Province; and Sister Michaela O’Connor, SHF, archivist for the Sisters of the Holy Family. -

Selected City Gates in Silesia – Research Issues1 Wybrane Zespoły Bramne Na Śląsku – Problematyka Badawcza

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS 3/2019 ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING DOI: 10.4467/2353737XCT.19.032.10206 SUBMISSION OF THE FINAL VERSION: 15/02/2019 Andrzej Legendziewicz orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-296X [email protected] Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Technology Selected City Gates in Silesia – research issues1 Wybrane zespoły bramne na Śląsku – problematyka badawcza Abstract1 The conservation work performed on the city gates of some Silesian cities in recent years has offered the opportunity to undertake architectural research. The researchers’ interest was particularly aroused by towers which form the framing of entrances to old-town areas and which are also a reflection of the ambitious aspirations and changing tastes of townspeople and a result of the evolution of architectural forms. Some of the gate buildings were demolished in the 19th century as a result of city development. This article presents the results of research into selected city gates: Grobnicka Gate in Głubczyce, Górna Gate in Głuchołazy, Lewińska Gate in Grodków, Krakowska and Wrocławska Gates in Namysłów, and Dolna Gate in Prudnik. The obtained research material supported an attempt to verify the propositions published in literature concerning the evolution of military buildings in Silesia between the 14th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Relicts of objects that have not survived were identified in two cases. Keywords: Silesia, architecture, city walls, Gothic, the Renaissance Streszczenie Prace konserwatorskie prowadzone na bramach w niektórych miastach Śląska w ostatnich latach były okazją do przeprowadzenia badań architektonicznych. Zainteresowanie badaczy budziły zwłaszcza wieże, które tworzyły wejścia na obszary staromiejskie, a także były obrazem ambitnych aspiracji i zmieniających się gustów mieszczan oraz rezultatem ewolucji form architektonicznych.