A CASE STUDY of the ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE a Thes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Table of Contents

2 FBC HOLDINGS LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Annual Report Table of contents OVERVIEW Group Structure 4 Independent Auditor’s Report 60 FBC Footprint 5 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 66 Our Pillars of Strength 6 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss Our Promise to Our Stakeholders 6 and Other Comprehensive Income 67 General Information 7 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 69 Report Profile 10 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 70 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 71 Financial Highlights 11 Company Statement of Financial Position 182 Group Chairman’s Statement 12 Company Statement of Comprehensive Income 183 Group Chief Executive’s Report 18 Company Statement of Changes in Equity 184 Sustainability Report 27 Company Statement of Cash Flows 185 Recognition and Awards 39 Notes to Company Financial Statements 186 Directors’ Report 40 Company Secretary’s Certification 47 Shareholders’ Information 190 Board of Directors 48 Notice of AGM 191 Corporate Governance 51 Proxy Form 193 FBC HOLDINGS LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2018 3 About This Report This integrated annual report was prepared for FBC Holdings and its subsidiaries. This annual report can be viewed at www.fbc.co.zw 4 FBC HOLDINGS LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Group Structure FBC Holdings Limited strength • diversity • service Consumer and Investment Banking Services Insurance Services FBC Insurance Company Limited 100 100 100 100 100 95% C M M E S Term NL B F F Trading R I + + S + + + A P S L H M S D B RA I + + F L I S + C S FBC HOLDINGS LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT -

Chairman's Statement

Herald, Sunday Mail, Chronicle, Sunday News million was 3% better than the ZWL$1,300,1 ZWL$19.2 million for 2019. Despite the good in the books of the Company at the close of CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT and Manica Post remained stable million recorded for the same period in 2019. revenue performance, the Division’s profit business on 4th December 2020. In view of underpinned by good subscriptions and Gross profit margin remained flat at 67% declined by 7% to ZWL$19.1 million (2019: the uncertainties associated with the retails sales. whilst net profit margin from operations ZWL$20.5 million) owing to a high cost base negative impact of Covid-19 and the drive to FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 declined from 17% in previous year to 12% and the associated inflationary pressures. capacitate the business by investing in new The rise of the social media notwithstanding, owing to an inflationary increase in technologies for all the Divisions of the demand for content remained high as operating costs. The increase in operating 10. Corporate Governance Group, the Board has recommended not to consumers continued to prefer accurate, costs was mainly driven by selling costs as The company’s Audit and Risk Committee, pay a final dividend. The ZWL2.0 cents per reliable and verified information on the Company vigorously defended its market Business Development Committee and the share interim dividend is therefore Covid-19, the economy, especially agriculture share in the very challenging operating Human Resources, Ethics and Remuneration recommended to be the final dividend for the and mining, politics and social issues that environment. -

Pioneers, Settlers, Aliens, Exiles: the Decolonisation of White Identity In

Pioneers, Settlers, Aliens, Exiles J. L. Fisher Pioneers, Settlers, Aliens, Exiles The decolonisation of white identity in Zimbabwe J. L. Fisher THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/pioneers_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fisher, J. L. (Josephine Lucy) Title: Pioneers, settlers, aliens, exiles : the decolonisation of white identity in Zimbabwe / J. L. Fisher. ISBN: 9781921666148 (pbk.) 9781921666155 (pdf) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Decolonization--Zimbabwe. Whites--Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe--Politics and government--1980- Zimbabwe--Race relations. Dewey Number: 320.96891 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Abbreviations. ix Preface . xi 1 ..Introduction. 1 2 ..Zimbabwe’s.discourse.of.national.reconciliation . 27 3 ..Re-inscribing.the.national.landscape. 55 4 ..Zimbabwe’s.narrative.of.national.rebirth. 79 5 ..Decolonising.settler.citizenship. 103 6 ..The.mobilisation.of.indigeneity. 131 7 ..The.loss.of.certainty. 173 8 ..Zimbabwe’s.governance.and.land.reform.crises—a.postscript.201 -

Zimbabwe: a Strategy of Tension

UNHCR Centre for Documentation and Research WRITENET Paper No. 04/2000 ZIMBABWE: A STRATEGY OF TENSION By Richard Carver Independent Researcher Oxford, United Kingdom July 2000 WriteNet is a Network of Researchers and Writers on Human Rights, Forced Migration, Ethnic and Political Conflict WriteNet is a Subsidiary of Practical Management (UK) E-mail: [email protected] THIS PAPER WAS PREPARED MAINLY ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THE PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO BE, EITHER EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THE PAPER ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF WRITENET OR UNHCR. ISSN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 2. ORIGINS OF THE PRESENT CRISIS............................................................................................1 2.1 THE MATABELELAND CRISIS...........................................................................................................1 2.2 ECONOMIC CRISIS ...........................................................................................................................3 2.3 LAND ..............................................................................................................................................4 2.4 CONCENTRATION OF POLITICAL -

Dollarization: the Case of Zimbabwe Joseph Noko

Dollarization: The Case of Zimbabwe Joseph Noko This article investigates the recent monetary experience of Zimbabwe with dollarization. It shows how dollarization has allowed Zimbabwe to quash hyperinflation, restore stability, increase budgetary discipline, and reestablish monetary credibil- ity. Zimbabwe’s hyperinflationary past and the stabilization meas- ures taken by the government are outlined, and the consequences defined. Problems arising from a lack of financial integration, an error in the choice of currency to dollarize under, and the inability of the government to enter into a formal dollarization agreement are discussed. Choice in Currency In his 1976 classic Choice in Currency, F. A. Hayek argued that “the pressure for more and cheaper money” led governments to monopolize the issuance of money and made inflation inevitable. He asked, “Why should we not let people choose freely what money they want to use?” The purpose of this article is to investigate Zimbabwe’s experience with choice in currency, given its recent history of hyperinflation and Cato Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2011). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Joseph Noko is General Manager of a small gold mining company in Zimbabwe and a partner in an economic development consultancy in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. He thanks James A. Dorn for constructive comments and Eric Bloch for helpful statis- tics and remarks. 339 Cato Journal its program of dollarization undertaken in 2008.1 We begin by setting the scene and describing the main events of Zimbabwe’s recent his- tory. The actions taken by the inclusive government to end the tyranny of hyperinflation are outlined, and the consequences of the decision to allow choice in currency are analyzed. -

Zse Annual Report 2019

ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ZSE Training Portal The ZSE Training portal is a user friendly, online educational platform that promotes financial education through the various investment resources available on the portal. 44 Ridgeway North Services available on the portal include: Highlands, Harare • Free Investment 101 Course Website: www.zsetraining.co.zw • Glossary for Capital Market Terms Email: [email protected] Tel: +263 (24) 2886830-5 • Upcoming Events and Training Facebook: Zimbabwe Stock Exchange Twitter: @ZSE_ZW LinkedIn: Zimbabwe Stock Exchange TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. 2019 HIGHLIGHTS 4 2. CORPORATE INFORMATION 7 3. OUR VISION, MISSION STATEMENT AND VALUES 10 4. THE ZSE’S BACKGROUND AND TRANSFORMATIONAL JOURNEY 11 5. STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY 14 7. CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 15 8. CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S STATEMENT 17 9. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 22 10. RISK MANAGEMENT REPORT 26 11. STATEMENT OF DIRECTORS’ REPONSIBILITY 27 12. INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 28 13. ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 33 ZSE Training Portal The ZSE Training portal is a user friendly, online educational platform that promotes financial education through the various investment resources available on the portal. 44 Ridgeway North Services available on the portal include: Highlands, Harare • Free Investment 101 Course Website: www.zsetraining.co.zw • Glossary for Capital Market Terms Email: [email protected] Tel: +263 (24) 2886830-5 • Upcoming Events and Training Facebook: Zimbabwe Stock Exchange Twitter: @ZSE_ZW LinkedIn: Zimbabwe Stock Exchange ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED 3 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 HIGHLIGHTS All Share Index Top 3 Liquid gained 57.33% Counters: to close at PPC at 27.56% 230.08 points Old Mutual at 17.59% CBZ at 15.75% The Market capitalisation of Annualised the ZSE was volatilty at 29% $29.77 billion as at 31 December 2019 2019 HIGHLIGHTS Foreign investor Top 3 Traded participation in 2019 was 34% compared Counters: to 31% in 2018. -

Zimbabwe After the Elections Hearing Committee On

S. HRG. 115–620 ZIMBABWE AFTER THE ELECTIONS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA AND GLOBAL HEALTH POLICY OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 6, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–433 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Mar 15 2010 13:55 Jun 05, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\115TH2D\DEC.6\36-433.TXT MIKE FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey MARCO RUBIO, Florida BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD, YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA AND GLOBAL HEALTH POLICY JEFF FLAKE, Arizona, Chairman TODD YOUNG, Indiana CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia TOM UDALL, New Mexico RAND PAUL, Kentucky JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 13:55 Jun 05, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\115TH2D\DEC.6\36-433.TXT MIKE FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER CONTENTS Page Young, Hon. -

FBC Group Profile

Contents 3 General Information 6 Message From The Group Chief Executive 7 Our Corporate Philosophy 7 FBC Holdings Core Values 8 Pillars of Strength 9 Our Promise to our Stakeholders 9 Our Journey 10 Our Current Operations 15 The FBC Footprint 16 The Group at a glance: An integrated business model 17 Our Comprehensive Governance Structure 18 FBC Holdings Board of Directors 19 Members of the Group Executive Committee 22 Board Committees 23 Our Summarised Group Financial Performance 24 Shareholding Information About This Profile This Group Corporate Profile can be viewed and downloaded at www.fbc.co.zw GRO UP C O R POR A T E PRO FILE 2 0 1 9 General Information FBC Holdings Limited Registered Office Transfer Secretaries Attorneys 6th Floor FBC Centre First Transfer Secretaries (Private) Limited Dube Manikai & Hwacha Legal Practi- 45 Nelson Mandela Avenue 1 Armagh Avenue, Eastlea tioners P.O. Box 1227, Harare P.O. Box 11 Harare Eastgate Building Zimbabwe Telephone: 263-024-782869 6th Floor, Goldbridge, Southwing Telephone: 263-024-700312/797770 Mobile: 263 772146157/8 Corner Sam Nujoma Street and Robert 263-024-708071/2 Mugabe Road Telex: 24512 FIRSTB ZW Independent Auditor P.O. Box CR 36, Cranborne, Harare Swift: FBCPZWHA Deloitte & Touche Telephone: 263-024-780351/2 Fax: 263-024-700761 West Block, Borrowdale Office Park Costa & Madzonga Legal Practitioners E-mail: [email protected] Borrowdale Road, Harare 10 York Avenue, Newlands Website: http://www.fbc.co.zw P.O. Box 267, Harare P.O. Box CY1221, Causeway, Harare Telephone: 263-024-852120-22 Telephone: 263-08644133638/9 263-024-852124-29 Fax: 263-024-852130 FBC Bank Limited Belgravia Private Banking Branch FBC Centre Branch Zvishavane Branch No. -

A History of the Rhodesian Stock Exchange: the Formative Years, 1946-1952

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. A History of the Rhodesian Stock Exchange: The Formative Years, 1946-1952 GEORGE KAREKWAIVENANI Department of Economic History, University of Zimbalnue Abstract This study attempts to fill the gap in the literature by tracing the history and operations of the Rhodesia Stock Exchange (RSE) between its establislunent in 1946 and 1952, shortly before tlie birth of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1953 lohen different dynamics came into play. It examines ivhy and liow the RSE was formed and documents its early history, as well as investigating the role and impact of the local bourse in tlie economy. Tlie study is divided into three sections. The first section examines the origins of the RSE and analyses the internal organisation of the Exchange, while the second gives an analysis of the RSE's operations and its influence on economic development between 1946 and 1952. Finally the conclusion assesses the RSE's role and performance and highlights some theoretical issues emerging from the study's findings. Introduction The Stock Exchange is a market where stocks and shares are purchased and sold and capital is raised for the purposes of industry and both local and central government.1 Markets for the trading of stocks and shares or securities have existed for centuries all over the world. -

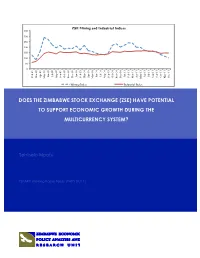

Does the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (Zse) Have Potential to Support Economic Growth During the Multicurrency System?

DOES THE ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE (ZSE) HAVE POTENTIAL POTENTIAL HAVE (ZSE) EXCHANGE STOCK ZIMBABWE THE DOES ZEPARUWorking (ZWPSPaper Series 01/11) Mpofu Sehliselo 100 150 200 250 300 350 50 0 Feb-09 Mar-09 TOSUPPORT ECONOMIC GROWTH DURING THE Apr-09 May-09 Jun-09 Jul-09 Aug-09 Sep-09 MULTICURRENCY SYSTEM? MULTICURRENCY Oct-09 Nov-09 Mining Index Mining Index Dec-09 ZSE and Mining Industrial Indices Jan-10 Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 May-10 Jun-10 Jul-10 Aug-10 Sep-10 Oct-10 Nov-10 Dec-10 Industrial Index Industrial Jan-11 Feb-11 Mar-11 Apr-11 May-11 Jun-11 Jul-11 Aug-11 Sep-11 Oct-11 Nov-11 Dec-11 DOES THE ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE (ZSE) HAVE POTENTIAL TO SUPPORT ECONOMIC GROWTH DURING THE MULTICURRENCY SYSTEM? By Sehliselo Mpofu Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit (ZEPARU) 55 Mull Road, Belvedere, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: +263-4-778423 Fax: +263-4-778415 Website: www.zeparu.co.zw E-mail: [email protected] ZEPARU Working Paper Series (ZWPS 01/11) Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ -

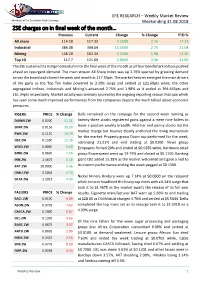

ZSE Charges on in Final Week of the Month…

EFE RESEARCH – Weekly Market Review Members of the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange Weekending 31.08.2018 ZSE charges on in final week of the month… Previous Current Change % Change YTD % All share 114.18 117.33 3.1500 2.76 17.33 Industrial 384.08 394.64 10.5600 2.75 21.04 Mining 158.20 161.34 3.1400 1.98 13.30 Top 10 117.7 121.69 3.9900 3.39 21.69 The ZSE sustained its rising momentum into the final week of the month as all four benchmark indices pushed ahead on resurgent demand. The main stream All Share Index was up 2.76% spurred by growing demand across the board and closed the week and month at 117.33pts. The market heavies emerged the main drivers of the gains as the Top Ten Index powered to 3.39% surge and settled at 121.69pts while, the other segregated Indices, Industrials and Mining’s advanced 2.75% and 1.98% as it ended at 394.645pts and 161.34pts respectively. Market activity was similarly spurred by the ongoing reporting season that saw which has seen some much improved performances from the companies despite the much talked about economic pressures. RISERS PRICE % Change Bulls remained on the rampage for the second week running as DAWN.ZW 0.0200 21.21 twenty-three stocks registered gains against a mere nine fallers to ZIMP.ZW 0.0156 20.00 leave a positive weekly breadth. Mid-tier and penny stocks led the market charge but heavies clearly anchored the rising momentum PWS.ZW 0.1150 19.79 for the market. -

The Effect of Dollarization on the Performance of the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange

THE EFFECT OF DOLLARIZATION ON THE PERFORMANCE OF THE ZIMBABWE STOCK EXCHANGE by MABEL BEN Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Management in Finance & Investment in the FACULTY OF COMMERCE LAW AND MANAGEMENT WITS BUSINESS SCHOOL at the UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR KALU OJAH DECLARATION I, Mabel Ben, declare that the research work reported in this dissertation is my own, except where otherwise indicated and acknowledged. It is submitted for the degree of Master of Management in Finance and Investment in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. This thesis has not, either in whole or in part, been submitted for a degree or diploma to any other universities. --------------------- Mabel Ben Signed at--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- On the------------------------------------- Day of----------------------------------------------2016 ii ABSTRACT Zimbabwe as a country went through severe economic crisis between the years 2000 and 2008. Hyperinflation, ill conception of policies by a desperate government that was in panic because of the shock that the crisis had on the economy, a declining exchange rate were among the serious challenges that were facing the economy. As investors and ordinary citizens scrambled for ways to store the value of their wealth, they all trooped to the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE) to buy shares. As the demand of shares increased, so did share prices. Share prices had stopped to reflect economic fundamentals as the stock exchange became a mere market place of raising money. Stock markets have several functions which are crucial to an economy among them giving support to and facilitation of the growth of key sectors as well as provide accurate signals for resource allocation (Aurangzeb, 2012).