Reflections on the Failure of the Union of Florence 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

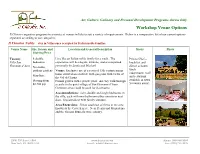

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

Borso D'este, Venice, and Pope Paul II

I quaderni del m.æ.s. – XVIII / 2020 «Bon fiol di questo stado» Borso d’Este, Venice, and pope Paul II: explaining success in Renaissance Italian politics Richard M. Tristano Abstract: Despite Giuseppe Pardi’s judgment that Borso d’Este lacked the ability to connect single parts of statecraft into a stable foundation, this study suggests that Borso conducted a coherent and successful foreign policy of peace, heightened prestige, and greater freedom to dispose. As a result, he was an active participant in the Quattrocento state system (Grande Politico Quadro) solidified by the Peace of Lodi (1454), and one of the most successful rulers of a smaller principality among stronger competitive states. He conducted his foreign policy based on four foundational principles. The first was stability. Borso anchored his statecraft by aligning Ferrara with Venice and the papacy. The second was display or the politics of splendor. The third was development of stored knowledge, based on the reputation and antiquity of Estense rule, both worldly and religious. The fourth was the politics of personality, based on Borso’s affability, popularity, and other virtues. The culmination of Borso’s successful statecraft was his investiture as Duke of Ferrara by Pope Paul II. His success contrasted with the disaster of the War of Ferrara, when Ercole I abandoned Borso’s formula for rule. Ultimately, the memory of Borso’s successful reputation was preserved for more than a century. Borso d’Este; Ferrara; Foreign policy; Venice; Pope Paul II ISSN 2533-2325 doi: 10.6092/issn.2533-2325/11827 I quaderni del m.æ.s. -

9. Chapter 2 Negotiation the Wedding in Naples 96–137 DB2622012

Chapter 2 Negotiation: The Wedding in Naples On 1 November 1472, at the Castelnuovo in Naples, the contract for the marriage per verba de presenti of Eleonora d’Aragona and Ercole d’Este was signed on their behalf by Ferrante and Ugolotto Facino.1 The bride and groom’s agreement to the marriage had already been received by the bishop of Aversa, Ferrante’s chaplain, Pietro Brusca, and discussions had also begun to determine the size of the bride’s dowry and the provisions for her new household in Ferrara, although these arrangements would only be finalised when Ercole’s brother, Sigismondo, arrived in Naples for the proxy marriage on 16 May 1473. In this chapter I will use a collection of diplomatic documents in the Estense archive in Modena to follow the progress of the marriage negotiations in Naples, from the arrival of Facino in August 1472 with a mandate from Ercole to arrange a marriage with Eleonora, until the moment when Sigismondo d’Este slipped his brother’s ring onto the bride’s finger. Among these documents are Facino’s reports of his tortuous dealings with Ferrante’s team of negotiators and the acrimonious letters in which Diomede Carafa, acting on Ferrante’s behalf, demanded certain minimum standards for Eleonora’s household in Ferrara. It is an added bonus that these letters, together with a small collection of what may only loosely be referred to as love letters from Ercole to his bride, give occasional glimpses of Eleonora as a real person, by no means a 1 A marriage per verba de presenti implied that the couple were actually man and wife from that time on. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Ferrara Venice Milan Mantua Cremona Pavia Verona Padua

Milan Verona Venice Cremona Padua Pavia Mantua Genoa Ferrara Bologna Florence Urbino Rome Naples Map of Italy indicating, in light type, cities mentioned in the exhibition. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust Court Artists Artists at court were frequently kept on retainer by their patrons, receiving a regular salary in return for undertaking a variety of projects. Their privileged position eliminated the need to actively seek customers, granting them time and artistic freedom to experiment with new materials and techniques, subject matter, and styles. Court artists could be held in high regard not only for their talents as painters or illuminators but also for their learning, wit, and manners. Some artists maintained their elevated positions for decades. Their frequent movements among the Italian courts could depend on summons from wealthier patrons or dismissals if their style was outmoded. Consequently their innovations— among the most significant in the history of Renaissance art—spread quickly throughout the peninsula. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust Court Patrons Social standing, religious rank, piety, wealth, and artistic taste were factors that influenced the ability and desire of patrons to commission art for themselves and for others. Frequently a patron’s portrait, coat of arms, or personal emblems were prominently displayed in illuminated manuscripts, which could include prayer books, manuals concerning moral conduct, humanist texts for scholarly learning, and liturgical manuscripts for Christian worship. Patrons sometimes worked closely with artists to determine the visual content of a manuscript commission and to ensure the refinement and beauty of the overall decorative scheme. -

The Relations of the Republic Of

Aleksandra V. Chirkova, Daria A. Ageeva , Evgeny A. Khvalkov THE RELATIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF VENICE AND THE MARQUISES D’ESTE IN THE MID-FOURTEENTH TO MID-FIFTEENTH CENTURY BASED ON THE LETTERE DUCALI FROM THE WESTERN EUROPEAN SECTION OF THE HISTORICAL ARCHIVE OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF THE RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: HUMANITIES WP BRP 174/HUM/2018 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE Aleksandra V. Chirkova1,2 Daria A. Ageeva3, Evgeny A. Khvalkov45 THE RELATIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF VENICE AND THE MARQUISES D’ESTE IN THE MID-FOURTEENTH TO MID- FIFTEENTH CENTURY BASED ON THE LETTERE DUCALI FROM THE WESTERN EUROPEAN SECTION OF THE HISTORICAL ARCHIVE OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF THE RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES6 The present study is devoted to the research into a set of the Venetian lettere ducali to the Marquises d’Este of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries collected by N.P. Likhachev (1862- 1936), Member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, stored in the Western European section of the Saint Petersburg Institute of History of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the preparation of their full-text critical publication. The lettere ducali are an excellent source to study the Serenissima and its continental and overseas domains. The source material of the Venetian lettere ducali have long and not without reason been considered and actively investigated by researchers as one of the most important sources on the economic, social, political, legal, environmental, cultural, and ethnic history of Venice. -

FERRARA SITE Ferrara, Italy 870 $110 Million

FERRARA SITE Ferrara, Italy Piazzale G. Donegani 12 Ferrara I-44122 Italy 870 50 hectares employees & Tel: +39 0532 46 7111 site footprint contractors ABOUT THE SITE ABOUT LYONDELLBASELL Ferrara Site and Technical Center is part of a multi-company complex located in the Emilia-Romagna LyondellBasell (NYSE: LYB) is one of the largest region, in Italy. This site has a long and illustrious history in the polyolefin industry and continues plastics, chemicals and refining companies to focus on this tradition of innovation thanks to the integration between its Giulio Natta Research Center, with pilot plant and laboratories, and the production area. The site comprises the polypropylene in the world. Driven by its 13,000 employees manufacturing operations as well as the catalyst production facilities. Polypropylene and advanced around the globe, LyondellBasell produces polyolefin resins are used in a wide variety of applications including food packaging, medical products, materials and products that are key to automotive components, and much more. advancing solutions to modern challenges like enhancing food safety through lightweight ECONOMIC IMPACT and flexible packaging, protecting the purity of water supplies through stronger and more Estimate includes yearly total for goods & services purchased and employee versatile pipes, and improving the safety, $110 million pay and benefits, excluding raw materials purchased (basis 2016) comfort and fuel efficiency of many of the COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT cars and trucks on the road. LyondellBasell sells products into approximately 100 countries LyondellBasell is committed to being a responsible, good neighbor in the communities where and is the world’s largest licensor of polyolefin we operate. -

Renaissance Tuscany Featured in Cigar Snob Magazine

Most of our readers don’t need to be sold on the wonders of over- seas travel. But in case there’s some travel-hating hermit reading this magazine in his mother’s basement, consider this from Bill Bryson’s Neither Here nor There: Travels in Europe: “But that’s the glory of foreign travel, as far as I am concerned. I don’t want to know what people are talking about. I can’t think of anything that excites a greater sense of childlike wonder than to be in a country where you are ignorant of almost everything. Suddenly you are five years old again. You can’t read anything, you have only the most rudimentary sense of how things work, you can’t even reliably cross a street without endangering your life. Your whole existence becomes a series of interesting guesses.” Bill Bryson put into words what I find so exhilarating about over- seas travel. Don’t get me wrong; the majority of my travel is to places where I speak the language and I’m not “endangering my life by crossing the street,” and I love that, too. In a strange way, though, trying to communicate with someone who is trying to help you in a foreign language is a hilarious and gratifying exercise. Ivan Ocampo and I spent a week in northern Italy to produce content for this issue. It wasn’t my first time there, but unlike previous trips, we weren’t there for vacation. We were there to work! I wrote about the trip in a piece titled The Italian Job on p.35. -

The Pearls of the Po: from Venice to Parma Aboard La Venezia September 18–26, 2021

The Pearls of the Po: From Venice to Parma Aboard La Venezia September 18–26, 2021 ITALY Venice Padua Adriatic Chioggia Sea Mantua Ferrara Po River Parma Ravenna Rialto Bridge, Venice The Po River, Italy’s longest river, winds through the heart of the country, ending its 400-mile journey at the Venetian Lagoon. On a delightful seven-night cruise along this incredible waterway, experience wonderful art, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and sumptuous palaces as you travel in luxury aboard the elegant La Venezia. Sailing gently from Venice to Parma, the ship stops along the way to visit the Renaissance gems of Ferrara and Parma, the Byzantine splendor of Ravenna, and the medieval grandeur of Virgil’s hometown, Mantua. Experience authentic Italian culture and cuisine, and be amazed by the art, architecture, and history of some of Italy’s most beautiful and historically rich cities. HIGHLIGHTS • Join the first cruise in a decade along this legendary waterway on the lavish, newly renovated super ship La Venezia. Visit remote, artistically rich towns that are underexplored by international visitors • Dock overnight in the heart of stunning Venice for early access to the city at sunrise, when the passageways are empty and serene and Venice’s sparkling piazze and palazzi are most captivating • Revel in the artistic splendors of Parma, where dazzling frescoes from Correggio and Parmigianino grace churches, and admire stunning 5th- and 6th-century mosaics in Ravenna • Explore the medieval and Renaissance city of Ferrara, innovatively designed as an “ideal city” by urban planner Biagio Rossetti. View medieval Estense Castle, with its storybook moat, drawbridges, and gorgeous towers • Delight in an exclusive, after-hours visit to Venice’s iconic Saint Mark's Basilica, an 11th-century showstopper filled with glittering gold mosaics and beautiful marble floors and statues Proprietary & Confidential For Discussion Only - Do Not Copy © 2020 Arrangements Abroad Inc. -

Udine Surroundings

UDINE SURROUNDINGS Aquileia A trip to the most important archeological seat of Friuli To reach Aquileia By train: from Udine station to Cervignano del Friuli station (cost 2,65€) and from there to Aquileia (8 km) with bus lines every hour. By car: from Udine, highway A23 in direction of Venice, exit E70 at Palmanova (17 km from Aquileia) following the SS 352 road signs to Aquileia. By bus: from Udine bus station to Aquileia every hour. The Touristic firm of Friuli, Turismo FVG, organizes every day (10.30 a.m. and 3.30 p.m. guided tours from 1st April to 30th June 2009 and September). Guided tour costs 7,50€ including admission to the crypts of the Basilica. Moreove, you can make use of the audio guide service at euros 4,00€ single and 7,00€ couple. For information and bookings you can contact all FVG Tourist Infopoints at phone: 0432 734100 or e-mail: [email protected] [email protected]. Aquileia. The origins of Aquileia date back a long time ago. In the place where, already in the proto-historic period, it used to trade amber from the North bartering it for seaborne items arriving from the Mediterranean and the Middle East docks, the Romans founded in 181 BC a colony. From a military outpost to a capital of the "X Regio Venetia et Histria", the city developed rapidly because of exclusive military reasons relating to expansionist aims of Roman Empire towards central European and Balkan regions. Aquileia became flourishing and prosperous thanks to the vast trade through a functional and capillary road network.