The Union of Florence, Crusade and Ottoman Hegemony in the Black Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

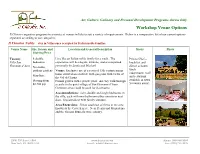

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

Borso D'este, Venice, and Pope Paul II

I quaderni del m.æ.s. – XVIII / 2020 «Bon fiol di questo stado» Borso d’Este, Venice, and pope Paul II: explaining success in Renaissance Italian politics Richard M. Tristano Abstract: Despite Giuseppe Pardi’s judgment that Borso d’Este lacked the ability to connect single parts of statecraft into a stable foundation, this study suggests that Borso conducted a coherent and successful foreign policy of peace, heightened prestige, and greater freedom to dispose. As a result, he was an active participant in the Quattrocento state system (Grande Politico Quadro) solidified by the Peace of Lodi (1454), and one of the most successful rulers of a smaller principality among stronger competitive states. He conducted his foreign policy based on four foundational principles. The first was stability. Borso anchored his statecraft by aligning Ferrara with Venice and the papacy. The second was display or the politics of splendor. The third was development of stored knowledge, based on the reputation and antiquity of Estense rule, both worldly and religious. The fourth was the politics of personality, based on Borso’s affability, popularity, and other virtues. The culmination of Borso’s successful statecraft was his investiture as Duke of Ferrara by Pope Paul II. His success contrasted with the disaster of the War of Ferrara, when Ercole I abandoned Borso’s formula for rule. Ultimately, the memory of Borso’s successful reputation was preserved for more than a century. Borso d’Este; Ferrara; Foreign policy; Venice; Pope Paul II ISSN 2533-2325 doi: 10.6092/issn.2533-2325/11827 I quaderni del m.æ.s. -

Conciliar Traditions of the Catholic Church I: Jerusalem-Lateran V Fall, 2015; 3 Credits

ADTH 3000 01 — Conciliar Traditions of the Catholic Church I: Jerusalem-Lateran V Fall, 2015; 3 credits Instructor: Boyd Taylor Coolman email: [email protected] Office: Stokes Hall 321N Office Hours: Wednesday 10:00AM-12:00 Telephone: 617-552-3971 Schedule: Tu 6:15–9:15PM Room: Stokes Hall 133S Boston College Mission Statement Strengthened by more than a century and a half of dedication to academic excellence, Boston College commits itself to the highest standards of teaching and research in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs and to the pursuit of a just society through its own accomplishments, the work of its faculty and staff, and the achievements of its graduates. It seeks both to advance its place among the nation's finest universities and to bring to the company of its distinguished peers and to contemporary society the richness of the Catholic intellectual ideal of a mutually illuminating relationship between religious faith and free intellectual inquiry. Boston College draws inspiration for its academic societal mission from its distinctive religious tradition. As a Catholic and Jesuit university, it is rooted in a world view that encounters God in all creation and through all human activity, especially in the search for truth in every discipline, in the desire to learn, and in the call to live justly together. In this spirit, the University regards the contribution of different religious traditions and value systems as essential to the fullness of its intellectual life and to the continuous development of its distinctive intellectual heritage. Course Description This course is the first in a two-course sequence, which offers a comprehensive introduction to the conciliar tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. -

9. Chapter 2 Negotiation the Wedding in Naples 96–137 DB2622012

Chapter 2 Negotiation: The Wedding in Naples On 1 November 1472, at the Castelnuovo in Naples, the contract for the marriage per verba de presenti of Eleonora d’Aragona and Ercole d’Este was signed on their behalf by Ferrante and Ugolotto Facino.1 The bride and groom’s agreement to the marriage had already been received by the bishop of Aversa, Ferrante’s chaplain, Pietro Brusca, and discussions had also begun to determine the size of the bride’s dowry and the provisions for her new household in Ferrara, although these arrangements would only be finalised when Ercole’s brother, Sigismondo, arrived in Naples for the proxy marriage on 16 May 1473. In this chapter I will use a collection of diplomatic documents in the Estense archive in Modena to follow the progress of the marriage negotiations in Naples, from the arrival of Facino in August 1472 with a mandate from Ercole to arrange a marriage with Eleonora, until the moment when Sigismondo d’Este slipped his brother’s ring onto the bride’s finger. Among these documents are Facino’s reports of his tortuous dealings with Ferrante’s team of negotiators and the acrimonious letters in which Diomede Carafa, acting on Ferrante’s behalf, demanded certain minimum standards for Eleonora’s household in Ferrara. It is an added bonus that these letters, together with a small collection of what may only loosely be referred to as love letters from Ercole to his bride, give occasional glimpses of Eleonora as a real person, by no means a 1 A marriage per verba de presenti implied that the couple were actually man and wife from that time on. -

Nicolaus of Cusa and the Council of Florence

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 18, Number 1, January 4, 1991 �TIillPhDosophy Nicolaus of Cusa antl the Council of Florence I. by Helga Zepp-LaRouche Schiller Institute founder Helga Zepp-LaRouche delivered Death, belief in the occult, and schisms in the Church. To this speech to the conference commemorating the 550th anni day, they are the threat tha� entire continents in the devel versary of the Council of Florence, which was held in Rome, oping sector will be wiped out by hunger, the increasingly Italy on May 5,1989. The speech was delivered in German species-threatening AIDS p�demic, Satanism's blatant of and has been translated by John Sigerson. fensive, and an unexampled process of moral decay. The parallels are all too evident, yet this has not halted our head In a period in which humanity seems to be swept into a long rush today into an age even darker than the fourteenth maelstrom of irrationality, it is useful to recall those moments century. The principal problem arises when Man abandons in history in which it succeeded in elevating itself from condi God and the search for a life inspired by this aim. As Nicolaus tions similar to those of today to the maximum clarity of of Cusa said, the finite being is evil to the degree that he Reason. The 550th anniversary of the Council of Florence is forgets that he is finite, believes with satanic pride that he the proper occasion for dealing with the ideas and events is sufficient unto himself, and lapses into a lethargy which which led to such a noble hour in the history of humanity. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

The Catholic Church Regarding African Slavery in Brazil During the Emancipation Period from 1850 to 1888

Bondage and Freedom The role of the Catholic Church regarding African slavery in Brazil during the emancipation period from 1850 to 1888 Matheus Elias da Silva Supervisor Associate Professor Roar G. Fotland This Master's Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at MF Norwegian School of Theology and is therefore approved as a part of this education. MF Norwegian School of Theology, [2014, Spring] AVH5010: Master's Thesis [60 ECTS] Master in Theology [34.658 words] 1 Table of Contents Chapter I – Introduction ..................................................................................................................5 1.1 - Personal Concern ....................................................................................................................5 1.2 - Background..............................................................................................................................5 1.3 - The Research........................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 - Methodology............................................................................................................................6 1.5 - Sources.................................................................................................................................... 9 1.6 - Research History .................................................................................................................... 9 1.7 - Terminology...........................................................................................................................10 -

Ferrara Venice Milan Mantua Cremona Pavia Verona Padua

Milan Verona Venice Cremona Padua Pavia Mantua Genoa Ferrara Bologna Florence Urbino Rome Naples Map of Italy indicating, in light type, cities mentioned in the exhibition. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust Court Artists Artists at court were frequently kept on retainer by their patrons, receiving a regular salary in return for undertaking a variety of projects. Their privileged position eliminated the need to actively seek customers, granting them time and artistic freedom to experiment with new materials and techniques, subject matter, and styles. Court artists could be held in high regard not only for their talents as painters or illuminators but also for their learning, wit, and manners. Some artists maintained their elevated positions for decades. Their frequent movements among the Italian courts could depend on summons from wealthier patrons or dismissals if their style was outmoded. Consequently their innovations— among the most significant in the history of Renaissance art—spread quickly throughout the peninsula. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust Court Patrons Social standing, religious rank, piety, wealth, and artistic taste were factors that influenced the ability and desire of patrons to commission art for themselves and for others. Frequently a patron’s portrait, coat of arms, or personal emblems were prominently displayed in illuminated manuscripts, which could include prayer books, manuals concerning moral conduct, humanist texts for scholarly learning, and liturgical manuscripts for Christian worship. Patrons sometimes worked closely with artists to determine the visual content of a manuscript commission and to ensure the refinement and beauty of the overall decorative scheme. -

The Roman Catholic Church and the Catholic Communion

Christianity The Roman Catholic Church and the Catholic Communion The Roman Catholic Church and the Catholic Communion Summary: The Church of Rome traces its roots to the apostles Peter and Paul, whose lineage continues through the papacy. Despite the Church of Rome’s separation from the Orthodox churches in 1054, and then with Protestant reformers in 1521, Catholics account for half of the world’s Christians today. The early church spoke of its fellowship of believers as “catholic,” a word which means “universal.” Today, the whole Christian church still affirms “one holy, catholic, and apostolic church” in the Nicene Creed. However, the term Catholic with a capital “C” also applies in common parlance to the churches within the Catholic Communion, centered in Rome. The Church of Rome is one of the oldest Christian communities, tracing its history to the apostles Peter and Paul in the 1st century. As it developed, it emphasized the central authority and primacy of the bishop of Rome, who became known as the Pope. By the 11th century, the Catholic Church broke with the Byzantine Church of the East over issues of both authority and doctrine. Over the centuries, several attempts have been made to restore union and to heal the wounds of division between the Churches. During the early 15th century, many in the Roman Church regarded the impending Turkish invasion of the Byzantine Empire as a “work of Providence” to bind divided Christianity together. In response, the Council of Florence envisioned union on a grandiose scale not only with the Greek Byzantine churches, but also with the Copts, Ethiopians, Armenians and Nestorians, as well as a reconfirmation of the 12th century union with the Maronite Church. -

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. V, Issue 7/ October 2017 Impact Factor: 3.4546 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org Dimension of Skanderbeg’s relations with the Holy See in the face of Ottoman invasions Prof. Ass. Dr. GJON BERISHA Assistant Professor Institute of History "Ali Hadri", Prishtina Abstract: One of the countries with which Skanderbeg had ongoing relationships and of a particular importance was the Holy See in Rome. In the 15th century, Rome represented, as it does today, the universal center of the Catholic Church (Holy See) and the capital of a powerful political state (papal state). As a Holy See, its jurisdiction extended to all structures of Catholic Church, hence, in Albanian territories as well. The advancement of the Ottoman armies in the Balkans, their approach to the borders of the Catholic Hungary, their outlet on the Adriatic coast, the aim of the sultans to penetrate into Central Europe and to cross the Italian Peninsula, had seriously worried Rome. The concern of Pope Eugene IV (1431-1447) grew even more after the Council of Florence (1439), where his projects for a joint crusade with the Eastern Church prove unsuccessful. It is precisely in these circumstances that Skanderbeg's resistance against the Ottoman armies gained a special strategic, political, military and ecclesial importance for Rome, both as a church and state. This study, mainly based on unpublished sources, those published in Latin and a rich bibliography, will treat the role of the Albanians and their warrior-king, George Kastrioti Skanderbeg in relation to the Holy See in the face of Ottoman invasions.