Regional Freight Study 2013; Facilities Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County by County Allocations

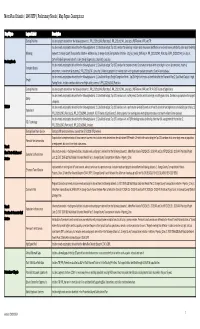

COUNTY BY COUNTY ALLOCATIONS Conference Report on House Bill 5001 Fiscal Year 2014-2015 General Appropriations Act Florida House of Representatives Appropriations Committee May 21, 2014 County Allocations Contained in the Conference Report on House Bill 5001 2014-2015 General Appropriations Act This report reflects only items contained in the Conference Report on House Bill 5001, the 2014-2015 General Appropriations Act, that are identifiable to specific counties. State agencies will further allocate other funds contained in the General Appropriations Act based on their own authorized distribution methodologies. This report includes all construction, right of way, or public transportation phases $1 million or greater that are included in the Tentative Work Program for Fiscal Year 2014-2015. The report also contains projects included on certain approved lists associated with specific appropriations where the list may be referenced in proviso but the project is not specifically listed. Examples include, but are not limited to, lists for library, cultural, and historic preservation program grants included in the Department of State and the Florida Recreation Development Assistance Program Small Projects grant list (FRDAP) included in the Department of Environmental Protection. The FEFP and funds distributed to counties by state agencies are not identified in this report. Pages 2 through 63 reflect items that are identifiable to one specific county. Multiple county programs can be found on pages 64 through 67. This report was produced prior -

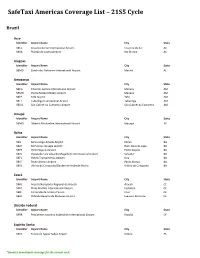

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

381 Part 117—Drawbridge Operation

Coast Guard, DOT Pt. 117 c. Betterments llll $llll other than an order of apportionment, Expected savings in repair or maintenance nor relieve any bridge owner of any li- costs: ability or penalty under other provi- a. Repair llll $llll b. Maintenance llll $llll sions of that act. Costs attributable to requirements of rail- [CGD 91±063, 60 FR 20902, Apr. 28, 1995, as road and/or highway traffic llll amended by CGD 96±026, 61 FR 33663, June 28, $llll 1996; CGD 97±023, 62 FR 33363, June 19, 1997] Expenditure for increased carrying capacity llll $llll Expired service life of old bridge llll PART 117ÐDRAWBRIDGE $llll OPERATION REGULATIONS Subtotal llll $llll Share to be borne by the bridge owner Subpart AÐGeneral Requirements llll $llll Contingencies llll $llll Sec. Total llll $llll 117.1 Purpose. Share to be borne by the United States 117.3 Applicability. llll $llll 117.4 Definitions. Contingencies llll $llll 117.5 When the draw shall open. Total llll $llll 117.7 General duties of drawbridge owners and tenders. (d) The Order of Apportionment of 117.9 Delaying opening of a draw. Costs will include the guaranty of 117.11 Unnecessary opening of the draw. costs. 117.15 Signals. 117.17 Signalling for contiguous draw- § 116.55 Appeals. bridges. (a) Except for the decision to issue an 117.19 Signalling when two or more vessels are approaching a drawbridge. Order to Alter, if a complainant dis- 117.21 Signalling for an opened drawbridge. agrees with a recommendation regard- 117.23 Installation of radiotelephones. ing obstruction or eligibility made by a 117.24 Radiotelephone installation identi- District Commander, or the Chief, Of- fication. -

AAPRCO & RPCA Members Meet to Develop Their Response to New Amtrak Regulations

Volume 1 Issue 6 May 2018 AAPRCO & RPCA members meet to develop their response to new Amtrak regulations Members of the two associations met in New Orleans last week to further develop their response to new regulations being imposed by Amtrak on their members’ private railroad car businesses. Several of those vintage railroad cars were parked in New Orleans Union Station. “Most of our owners are small business people, and these new policies are forcing many of them to close or curtail their operations,” said AAPRCO President Bob Donnelley. “It is also negatively impacting their employees, suppliers and the hospitality industry that works with these private rail car trips,” added RPCA President Roger Fuehring. Currently about 200 private cars travel hundreds of thousands of miles behind regularly scheduled Amtrak trains each year. Along with special train excursions, they add nearly $10 million dollars in high margin revenue annually to the bottom line of the tax-payer subsidized passenger railroad. A 12% rate increase was imposed May 1 with just two weeks’ notice . This followed a longstanding pattern of increases taking effect annually on October 1. Cost data is being developed by economic expert Bruce Horowitz for presentation to Amtrak as are legal options. Members of both organizations are being asked to continue writing their Congress members and engaging the press. Social media is being activated and you are encouraged to follow AAPRCO on Facebook and twitter. Successes on the legislative front include this Congressional letter sent to Amtrak's president and the Board and inclusion of private car and charter train issues in recent hearings. -

2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan

final report 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan prepared for Florida Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Charles River Associates June 2005 final report 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan prepared for Florida Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Charles River Associates Inc. June 2005 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 Purpose........................................................................................................................... ES-1 Florida’s Rail System.................................................................................................... ES-2 Freight Rail and the Florida Economy ....................................................................... ES-7 Trends and Issues.......................................................................................................... ES-15 Future Rail Investment Needs .................................................................................... ES-17 Strategies and Funding Opportunities ...................................................................... ES-19 Recommendations........................................................................................................ -

2045 MTP | Preliminary Needs | Map Figure Descriptions

MetroPlan Orlando | 2045 MTP | Preliminary Needs | Map Figure Descriptions Map Figure Legend Label Description Existing Priorities Includes projects derived from the following datasets: 1. PPL_2021to2040_Point.shp; 2. PPL_2021to2040_Line.shp; 3. PDF Review of PPL and TIP. Includes needs and projects derived from the following datasets: 1. Data Model output: Top 100 corridors for widening. corridors which have been identified as a need and have a potential to widen beyond existing Widening segment; 2. Orange County Transportation Initiative - Additions.shp; 3. Orange County Transportation Initiative - LOS_ALL_Needs_2045.shp; 4. PPL_2021to2040_Point.shp; 5. PPL_2021to2040_Line.shp; 6. Roadway Needs Central Florida Expressway Authority - Lake_Orange_Express.shp, OsceolaCo_Loop.shp Includes needs and projects derived from the following datasets: 1. Data Model output: Top 100 corridors for complete streets. Constrained corridors which score high in access & connectivity, health & Complete Streets environment, or investment & economy; 2. PPL_2021to2040_Line.shp; 3. Widening projects from existing plans which go beyond roadway constraints (2 and 4 lane roadways) Includes needs and projects derived from the following datasets: 1. Data Model Output, Freight Congestion Needs - Top 25 freight bottlenecks as identified within the Statewide Plan; 2. Data Model Output, Freight Freight Parking Needs - Includes corridors which serve freight activity centers; 3. PPL_2021to2040_Point.shp Existing Priorities Includes projects derived from the following datasets: 1. PPL_2021to2040_Point.shp; 2. PPL_2021to2040_Line.shp; 3. PDF Review of PPL and TIP; 4. FDOT Routes of Significance Includes needs and projects derived from the following datasets: 1. Data Model output: Top 100 corridors with a safety need. Corridors which score high on safety goal criteria. Corridors may duplicate other project Safety categories. -

Discussion Orange Blossom Express Rail

US-441 Corridor (Orange Blossom Express) Rail Alternatives Analysis Local Matching Funds Board of County Commissioners February 15, 2011 Presentation Outline • Background • Cost Allocation • Requested Action Presentation Outline • Background • Cost Allocation • Requested Action Background • Proposed 35-mile Commuter Rail • Downtown Orlando to Eustis/Tavares • Existing Florida Central Railroad Corridor • Feeder to SunRail Background • Feasibility Study Completed – 2001 • Included in MetroPlan Orlando Cost-Feasible LRTP - 2009 • Alternatives Analysis is next step in Federal Funding process • Commissioner Brummer request to pursue Federal Funding – Jan 2010 • FDOT Submitted Federal Grant Application in 2010 – not selected for funding Background Presentation Outline • Background • Cost Allocation • Requested Action Cost Allocation • FDOT pursued Federal Grant in 2010 – 80% Federal – 10% State – 10% Local – Application not selected for funding • FDOT now committing 75% of Funding – 75% State – 25% Local • MetroPlan MPO Area (50%) • Lake-Sumter MPO Area (50%) Cost Allocation • Cost Sharing Methodology – Station Location – Passenger boarding estimates in Feasibility Study • Orlando MPO Area Funding Partners – Orange County – City of Orlando – City of Apopka Cost Allocation Funding Partner Percentage Amount State 75% $1,275,000 Local 25% $425,000 MetroPlan Orlando Area 12.5% $212,500 City of Orlando 6.25% $106,250 Orange County 3.13% $53,125 City of Apopka 3.13% $53,125 Lake-Sumter MPO Area 12.5% $212,500 Lake County 6.25% $106,250 Lake County Municipalities 6.25% $106,250 Total 100% $1,700,000 Presentation Outline • Background • Cost Allocation • Requested Action Requested Action • Approval of a conditional commitment of matching funds to the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) in the amount of $53,125 for the US- 441 Corridor/Orange Blossom Express (Downtown Orlando to Eustis/Tavares Area) Alternatives Analysis, subject to approval of a subsequent agreement between Orange County and FDOT. -

I N V E S T I N G

INVESTING IN Program Highlights | 2016 1 INVESTING IN The SIS n 2003, the Florida Legislature and Governor established the Strategic Intermodal System (SIS) to enhance Florida’s transportation mobility and Ieconomic competitiveness. The SIS is a statewide network of high-priority transportation facilities, including the State’s largest and most significant WHAT IS THE airports, spaceports, deep-water seaports, freight rail terminals, passenger rail and intercity bus terminals, rail corridors, waterways and highways. These facilities represent the state’s primary means for moving people and freight between Florida’s diverse regions, as well as between Florida and other states STRATEGIC and nations. SIS Facilities are designated through the use of objective criteria and thresholds based on quantitative measures of transportation and economic activity. These facilities meet high levels of people and goods movement and INTERMODAL generally support major flows of interregional, interstate, and international travel and commerce. Facilities that do not yet meet the established criteria and thresholds for SIS designation, but are expected to in the future are referred to as Emerging SIS. These facilities experience lower levels of people SYSTEM? and goods movement but demonstrate strong potential for future growth and development. The designated SIS and Emerging SIS includes 17 commercial service airports, two spaceports, 12 public seaports, over 2,300 miles of rail corridors, over 2,200 miles of waterways, 34 passenger terminals, seven rail freight terminals, and over 4,600 miles of highways. These hubs, corridors and connectors are the fundamental structure which satisfies the transportation needs of travelers and visitors, supports the movement of freight, and provides transportation links to external markets. -

T.J. Fish, AICP Executive Director Creating New Trails in Central Florida

T.J. Fish, AICP Executive Director Creating new trails in Central Florida Close the Gaps 6/21/2013 Heart of Florida “Mt. Dora “Heart of Bikeway” Florida Loop” Coast to Coast Spurs Van Fleet State Trail Gap 6/21/2013 5 South Sumter Connector Trail New trail alignment for study in Sumter 6/21/2013 6 Lake & Seminole Gap 6/21/2013 7 Lake & Marion Gap 6/21/2013 8 Mount Dora Bike Way Gap 6/21/2013 9 What is our Transit future going to look like? ChamberLake County – Alliance TDP Major Update of Lake County 5-30-201310 October 10, 2012 Where do we go from here, in the next ten years? Maintain or expand the types of transportation service Paratransit service / demand response Demand Response – general public Flexibly routed / deviated routes Fixed route Express routes Bus Rapid Transit Rail service What are the priorities for projects? ChamberLake County – Alliance TDP Major Update of Lake County 5-30-201311 October 10, 2012 Rapid UZA Growth Between 2000 – 2010 Between 2000 and 2010 the population of the Lady Lake UZA grew from 50,721 to 112,991 people (+ 123%)…Orlando +32%...Leesburg +35% 2000 2010 Partially due to an increase in the UZA size from 50 to 71 square miles = 1,000 people ChamberLady County Transit Alliance Developmen oft Plan Lake (TDP) Major County Update 125-30-2013May 22, 2012 LakeXpress Service Oct 2009- Oct 2010- Oct 2011- Percent LakeXpress Route Sept 2010 Sept 2011 Sept 2012 Change Route 1: Lady Lake/Eustis via US441 128,959 136,147 161,873 25.52% Route 2: City of Leesburg 45,056 46,679 55,110 22.31% Route 3: City of Mount -

Statewide Aviation Economic Impact Study Update

FLORIDA Statewide Aviation Economic Impact Study Update TECHNICAL REPORT AUGUST 2014 FLORIDA STATEWIDE AVIATION ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY UPDATE August 2014 Florida Department of Transportation Aviation and Spaceports Office This report was prepared as an effort of the Continuing Florida Aviation System Planning Process under the sponsorship of the Florida Department of Transportation. A full technical report containing information on data collection, methodologies, and approaches for estimating statewide and airport specific economic impacts is available at www.dot.state.fl.us/aviation/economicimpact.shtm. More information on the Florida’s Aviation Economic Impact Study can be obtained from the Aviation and Spaceports Office by calling 850-414-4500. Florida Department of Transportation – Aviation & Spaceports Office Statewide Aviation Economic Impact Study Update August 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1-1 OVERVIEW OF AVIATION’S ECONOMIC IMPACT IN FLORIDA ............................................1-1 TYPES OF AVIATION ECONOMIC IMPACT MEASURED ......................................................1-2 APPROACH TO MEASURING AVIATION ECONOMIC IMPACT IN FLORIDA ........................1-2 AIRPORT ECONOMIC IMPACTS ............................................................................................1-2 VISITOR ECONOMIC IMPACTS .............................................................................................1-3 -

N a S a Facts

National Aeronautics and Space Administration The NASA Railroad he NASA Railroad is a 38-mile industrial Wilson Yard, slightly west of the geographical loca- Tshort line on the Kennedy Space Center in tion of Wilson’s Corners. Central Florida. It connects to additional Air East of Wilson Yard, the line divides with a Force trackage on Cape Canaveral Air Force nine-mile branch going south to NASA’s Vehicle Station. The railroad system is government owned Assembly Building and the Kennedy Space Cen- and contractor operated. ter Industrial Area, the other another nine-mile branch going east toward the Atlantic Ocean for 1963 – 1983: service to the NASA launch pads and the inter- facts In 1963, the Florida East Coast Railway built a change with the Air Force track. 7.5- mile connection to the Kennedy Space Center In the late 1970s, NASA acquired three from its mainline just north of Titusville, Fla. The World War II-era ex-U.S Army Alco S2 locomo- line required a drawbridge to be built over the In- tives for local switching in the area of the Vehicle dian River, part of the Intercoastal Waterway. The Assembly Building and the KSC Industrial Area. steel bridge and its approaches are approximately The Florida East Coast provided track mainte- a half-mile long, built on concrete pilings. The nance, crews and locomotive power for the arriving draw span stays open continuously until a train ap- and departing traffic. proaches, and the crew activates a switch to lower it. 1983 - Present: The Florida East Coast connection joined 28 NASA purchased the Florida East Coast NASA miles of NASA-constructed track at a junction portion of the railroad line in June 1983. -

Spaceport News John F

Feb. 11, 2011 Vol. 51, No. 3 Spaceport News John F. Kennedy Space Center - America’s gateway to the universe www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/snews/spnews_toc.html Tank fixed, Discovery rolls out for STS-133 launch By Frank Ochoa-Gonzales Spaceport News s New York Yankee great Yogi Berra once said: “It’s Adéjà vu all over again.” On the final night of January 2011, in front of Kennedy work- ers, their friends and family, space shuttle Discovery trekked its way from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Pad 39A. It was the second time Dis- covery rolled out for its STS-133 mission to the International Space Station, which now is targeted to launch Feb. 24 at 4:50 p.m. EST “Anytime we have a long flow of challenges, which we’ve had for STS-133, that makes the final out- come even sweeter,” said Stephanie Stilson, Discovery’s NASA flow director for the past 11 missions. So when we finally get to the launch we really appreciate the work that NASA/Kim Shiflett has happened and all the long hours Xenon lights illuminate space shuttle Discovery as it makes its nighttime trek, known as “rollout,” from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Pad 39A at our team has put in.” Kennedy Space Center on Jan. 31. The first rollout came last year For Discovery’s flow team, the in late September when Discovery xenon lights not only highlighted Follow along on launch day was supposed to make its last flight the STS-133 stack, but the many NASA’s Launch Blog is set to begin about five hours prior to liftoff, and will highlight to the space station in November.