Aviation Emergency Response Guidebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

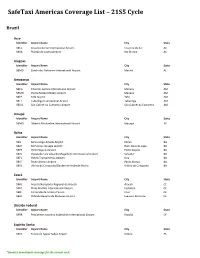

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Aviation Human Factors Industry News August 2, 2007 Airline

Aviation Human Factors Industry News August 2, 2007 Vol. III. Issue 27 Airline employee dies in accident at Mississippi Tunica Airport The Federal Aviation Administration and the National Transportation Safety Board are looking into the death of a worker at the Tunica Airport. Alan Simpson, a flight mechanic for California- based Sky King Incorporated, died in an accident at the airport on July 10. According to a preliminary NTSB report, Simpson was attempting to close the main cabin door on a flight that was preparing to take off from Tunica when he lost his grip and fell ten feet to the ground. Simpson suffered a skull fracture and broken ribs, and died the next day at The MED. The NTSB report says it was very windy and raining in Tunica that afternoon, but does not say if weather was a factor in Simpson's fall Closing the main cabin door was not part of Simpson's duties. According to a Sky King official, he was doing a favor for a flight attendant. Sky King's president, Greg Lukenbill, called Simpson's death a tragic accident, saying, "he was a highly skilled flight mechanic who dedicated his work to the safety of our aircraft. Al's large personality integrity and big smile will be greatly missed by everyone here at Sky King." The Tunica County Airport Commission's executive director, Cliff Nash, said the airport's insurance company had advised him not to comment on the matter. NTSB Hearing on Flight 5191 For loved ones, 'it is profoundly sad' During a break in the National Transportation Safety Board hearing in Washington, Kevin Fahey reflected on his son’s life. -

IC-A210 Instruction Manual

IC-A210.qxd 2007.07.24 2:06 PM Page a INSTRUCTION MANUAL VHF AIR BAND TRANSCEIVER iA210 This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. Operation is subject to the condition that this device does not cause harmful interference. IC-A210.qxd 2007.07.24 2:06 PM Page b IMPORTANT FEATURES READ ALL INSTRUCTIONS carefully and completely ❍ Large, bright OLED display before using the transceiver. A fixed mount VHF airband first! The IC-A210 has an organic light emitting diode (OLED) display. All man-made lighting emits its own SAVE THIS INSTRUCTION MANUAL — This in- light and display offers many advantages in brightness, not bright- ness, vividness, high contrast, wide viewing angle and response time struction manual contains important operating instructions for compared to a conventional display. In addition, the auto dimmer the IC-A210. function adjusts the display for optimum brightness at day or night. ❍ Easy channel selection It’s fast and easy to select any of memory channels in the IC-A210. EXPLICIT DEFINITIONS The “flip-flop” arrow button switches between active and standby channels. The dualwatch function allows you to monitor two channels The explicit definitions below apply to this instruction manual. simultaneously. In addition, the history memory channel stores the last 10 channels used and allows you to recall those channels easily. WORD DEFINITION ❍ GPS memory function Personal injury, Þre hazard or electric shock When connected to an external GPS receiver* equipped with an air- RWARNING may occur. port frequency database, the IC-A210 will instantly tune in the local CAUTION Equipment damage may occur. -

Improving Safety by Integrating Changeable LED Message Signage to the Airfield

Improving Safety by Integrating Changeable LED Message Signage to the Airfield Brandon A’Hara, Josh Crump, Jimmy Deter, Victoria Haky, Andrew Macpherson, Jake Nguyen, Joe Schrantz The Ohio State University 2013-2014 FAA Design Competition for Center for Aviation Studies Universities, Runway Safety/Runway Incursions/Runway Excursion Challenge Dr. Seth Young, Faculty Advisor April, 2014 COVER PAGE Title of Design: __Improving Safety by Integrating Changeable LED Message Signage to the Airfield Design Challenge addressed: __Runway Safety / Runway Incursions / Excursions Challenge_______ University name: ___The Ohio State University_______ Team Member(s) names: __Brandon A’Hara, Josh Crump, Jimmy Deter___________________ _______________________Victoria Haky, Andrew Macpherson, Jake Nguyen, Joe Schrantz____ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ Number of Undergraduates: ____5______________________ Number of Graduates: ________2_______________________ Advisor(s) name: ________Seth Young, Ph.D._______________ 1 | Page FAA Design Competition Entry| A’Hara, Crump, Deter, Haky, Macpherson, Nguyen, Schrantz Executive Summary This report addresses the FAA Design Competition for Universities' Runway Safety/Runway Incursions/Runway Excursion Challenge for the 2013-2014 -

Wireless Backhaul Evolution Delivering Next-Generation Connectivity

Wireless Backhaul Evolution Delivering next-generation connectivity February 2021 Copyright © 2021 GSMA The GSMA represents the interests of mobile operators ABI Research provides strategic guidance to visionaries, worldwide, uniting more than 750 operators and nearly delivering actionable intelligence on the transformative 400 companies in the broader mobile ecosystem, including technologies that are dramatically reshaping industries, handset and device makers, software companies, equipment economies, and workforces across the world. ABI Research’s providers and internet companies, as well as organisations global team of analysts publish groundbreaking studies often in adjacent industry sectors. The GSMA also produces the years ahead of other technology advisory firms, empowering our industry-leading MWC events held annually in Barcelona, Los clients to stay ahead of their markets and their competitors. Angeles and Shanghai, as well as the Mobile 360 Series of For more information about ABI Research’s services, regional conferences. contact us at +1.516.624.2500 in the Americas, For more information, please visit the GSMA corporate +44.203.326.0140 in Europe, +65.6592.0290 in Asia-Pacific or website at www.gsma.com. visit www.abiresearch.com. Follow the GSMA on Twitter: @GSMA. Published February 2021 WIRELESS BACKHAUL EVOLUTION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................................5 -

The Federal Aviation Administration Suspected Unapproved Parts Program: the Need to Eliminate Safety Risks Posed by Unapproved Aircraft Ap Rts, 65 J

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 65 | Issue 4 Article 6 2000 The edeF ral Aviation Administration Suspected Unapproved Parts Program: The eedN to Eliminate Safety Risks Posed by Unapproved Aircraft aP rts Beverly Jane Sharkey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Beverly Jane Sharkey, The Federal Aviation Administration Suspected Unapproved Parts Program: The Need to Eliminate Safety Risks Posed by Unapproved Aircraft aP rts, 65 J. Air L. & Com. 795 (2000) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol65/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION SUSPECTED UNAPPROVED PARTS PROGRAM: THE NEED TO ELIMINATE SAFETY RISKS POSED BY UNAPPROVED AIRCRAFT PARTS BEVERLY JANE SHARKEY* ** I. BACKGROUND "To promote the highest level of aviation safety by eliminating the potential safety risk posed by the entry of 'unapproved parts' in the U.S. aviation community."' T HE ISSUE of suspected unapproved parts is not new. Regu- lations relating to the design, manufacture, operation, maintenance, and alteration of aviation products and parts have existed for years. These regulations, reinforced with surveil- lance and enforcement activities by the Federal Aviation Admin- istration (FAA), have been key elements in maintaining a high level of safety in the air transportation system. Yet, some parts circumvent these regulatory controls and enter the aviation stream of commerce as suspected unapproved parts-SUPs. -

Icom Black Box Receiver

AOR Presents Two New Wide Coverage Professional Grade Communications Receivers AR2300 “Black Box” receiver It’s a new generation of software controlled black box receivers! Available in professional and consumer versions, the AR2300 covers 40 KHz to 3.15 GHz* and monitors up to three channels simultaneously. Fast Fourier Transform algorithms provide a very fast and high level of signal processing, allowing the receiver to scan through large frequency segments quickly and accurately. All functions can be controlled through a PC running Windows XP or higher. Advanced signal detection capabilities can find hidden transmitters. An optional external IP control unit enables the AR2300 to be fully controlled from a remote location and send received signals to the control point via the internet. It can also be used for unattended long-term monitoring by an internal SD audio recorder or spectrum recording with optional AR-IQ software for laboratory signal analysis. AR5001D performs with accuracy, sensitivity and speed Developed to meet the monitoring needs of security professionals and government agencies, the AR5001D features ultra-wide frequency coverage from 40 KHz to 3.15 GHz*, in 1Hz steps with 1ppm accuracy and no interruptions. Up to three channels can be monitored simultaneously. Fast Fourier Transform algorithms provide a very fast and high level of digital signal processing, allowing the receiver to scan through large frequency segments quickly and accurately. Controlled through a PC running Windows XP or higher, it is available in both professional and consumer versions. With its popular analog signal meter and large easy-to-read digital spectrum display, the AR5001D is destined to extend the legend of the AR5000A+3. -

Icom AV Retail Product & Price Catalog

U.S. Avionics Retail Product & Price Catalog October 2017 All stated specifications are subject to change without notice or obligation. All Icom radios meet or exceed FCC regulations limiting spurious emissions. © 2017 Icom America Inc. The Icom logo is a registered trademark of Icom Inc. The IDAS™ name and logo are trademarks of Icom Inc. All other trademarks remain the property of their respective owners. Contents Handhelds ............................................................................................................................................. 4 A14 .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A24 / A6 ............................................................................................................................................. 8 A25 .................................................................................................................................................. 11 Mobiles / Panel Mounts ........................................................................................................................ 13 A120 ................................................................................................................................................ 14 A220 ................................................................................................................................................ 17 Fixed Comms Infrastructure ................................................................................................................ -

Two Way Radio Proposal

City of Charlotte City of Charlotte Bid Number: 269-2019-054 Radios and Communication Equipment TWO WAY RADIO OF CAROLINA, INC. A Legend in Communications since 1956 FOR INFORMATION CONTACT: RJ Ochoa Jonathan Sable Regional Manger Phone: (704) 372-3444 Fax: (704) 372-7059 Email: [email protected] [email protected] “A LEGEND IN COMMUNICATIONS SINCE 1956.” $SULO %LG1XPEHU &KDUORWWH0HFNOHQEXUJ*RYHUQPHQW&HQWHU 3URFXUHPHQW6HUYLFHV'LYLVLRQWK )ORRU (DVW)RXUWK6WUHHWWK )ORRU± &0*& &KDUORWWH1& $WWQ'DYLG7DWH &RYHU/HWWHU 'HDU&LW\RI&KDUORWWH 7KDQN\RXIRUWKHLQYLWDWLRQWRSODFHDELGIRUWKH&LW\RI&KDUORWWH¶V5DGLRDQG&RPPXQLFDWLRQ (TXLSPHQW 6LQFH7ZR:D\5DGLRRI&DUROLQD,QFKDVEHHQPHHWLQJWKHUDGLRFRPPXQLFDWLRQVQHHGVRI WKHJUHDWHU&KDUORWWHDUHD7ZR:D\5DGLRRI&DUROLQDLVRQHRI1RUWK&DUROLQD VSUHPLHUWZRZD\ UDGLRVKRSVDQGWKLV\HDUZHDUHFHOHEUDWLQJRXUWK\HDU :HDUHORFDWHGULJKWKHUHLQ&KDUORWWHPLOHVIURPWKH&KDUORWWH0HFNOHQEXUJ*RYHUQPHQW &HQWHU7KLVHQVXUHVWKDW\RXZLOOKDYHWKHIDVWHVWUHVSRQVHRIDQ\YHQGRU:HZHUHDZDUGHGWKH &KDUORWWH5DGLRDQG&RPPXQLFDWLRQV(TXLSPHQW&RQWUDFWIRUWKH\HDUVUHSUHVHQWLQJ +DUULVDQG()-RKQVRQ&RPPXQLFDWLRQV(TXLSPHQWUHSUHVHQWLQJ,&20DQGKDYH HDUQHGWKHWUXVWRIVRPHRI&KDUORWWH¶VPRVWUHFRJQL]DEOHQDPHVLQFOXGLQJ%DQNRI$PHULFD:HOOV )DUJR%DQN&KDUORWWH+RUQHWV1$6&$5+DOORI)DPH&KDUORWWH&RQYHQWLRQ&HQWHUDQGWKH %OXPHQWKDO3HUIRUPLQJ$UWV&HQWHU 7ZR:D\5DGLRRI&DUROLQDUHDOL]HVWKHLPSRUWDQFHRIVXSHULRUFRPPXQLFDWLRQVLQWRGD\ V3XEOLF VDIHW\HQYLURQPHQWV:HUHSUHVHQWWKHEHVW3XEOLF6DIHW\UDGLRPDQXIDFWXUHUV 0RWRUROD,&20 DQG()-RKQVRQ ZKLFKJLYHVXVDXQLTXHSHUVSHFWLYHWRXQGHUVWDQGDOOWKHWHFKQRORJ\RSWLRQV DYDLODEOHWRWKH&LW\RI&KDUORWWH7KLVJLYHVXVWKHH[FOXVLYHDELOLW\WRGHOLYHUWKHEHVWRYHUDOO -

Public Notice

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report Number: 6940 Date of Report: 06/22/2011 Wireless Telecommunications Bureau Site-By-Site Action Below is a listing of applications that have been acted upon by the Commission. AF - Aeronautical and Fixed File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0004722067 06/16/2011 WGV5 Piper Aircraft, Inc. AM G 0004762575 06/14/2011 KYM8 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc CA G 0004769570 06/17/2011 WQBC823 Armstrong World Ind CA G 0004696254 06/15/2011 WEU9 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc MD G 0004696276 06/15/2011 WQKE553 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc MD G 0004696335 06/15/2011 KCD4 Aviation Spectrum Resources Inc MD G 0004696240 06/15/2011 WQNW240 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004696247 06/15/2011 WQNW241 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004696252 06/15/2011 WQNW242 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004696257 06/15/2011 WQNW236 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004696262 06/15/2011 WQNW237 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004696267 06/15/2011 WQNW238 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004696284 06/15/2011 WQNW239 Aviation Spectrum Resources, Inc NE G 0004698306 06/15/2011 WQNW235 Bridgeport, City of NE G 0004763499 06/15/2011 WQNW204 Alpha Natural Resources Services LLC NE G Page 1 AI - Aural Intercity Relay File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0004771148 06/18/2011 WLJ933 CITICASTERS LICENSES, INC. -

Aviation Safety Oversight and Failed Leadership in the FAA

Table of Contents I. Executive Summary……………………………………………………….…….....…….2 II. Overview……………….......……………………………………………………………..3 III. Table of Acronyms……………………………………………………….……....….…...9 IV. Findings……..…………………………………………………………………………...11 V. Introduction………………………………………………………………………...…...14 A. The Federal Aviation Administration …………….…….……………….……...…….15 B. History of Safety Concerns in the FAA……….……………………..……..……...…16 C. Whistleblowers……………………………………………………………………..…20 D. FAA Aviation Safety and Whistleblower Investigation Office………………………22 VI. Committee Investigation…………………………………………….............................24 A. Correspondence with the FAA………………………………………………..….......24 B. Concerns Surrounding the FAA’s Responses.……...…………………………..…….28 C. Other Investigations………………………………………………………………..…32 VII. Whistleblower Disclosures………………………………..……………………………38 A. Boeing and 737 Max………………………………………………………………….38 B. Abuse of the FAA’s Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP)……………………... 47 C. Atlas Airlines………………………………………………………………………….59 D. Allegations of Misconduct at the Honolulu Flight Standards District Office………...66 E. Improper Training and Certification………………………………………………….73 F. Ineffective Safety Oversight of Southwest Airlines…………………………………..82 VIII. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………....99 IX. Recommendations…………………………………………………..……….………...101 1 I. Executive Summary In April of 2019, weeks after the second of two tragic crashes of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft, U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation staff began receiving information -

Fujii PPS Docu Rvsd Vs101.0 13Aug2019

Research paper on PPS Version 101.0 x modified on 13Aug,2019 x original by Shigeru Fujii on 20Apr, 2017 PPS = Proactive and Predictive System to mitigate/minimize/eliminate PICs fatal decision-making errors by Deep Learning AI PPS SLOGAN = “ Trap Human Errors with PPS “ ① Help pilots trap errors that might occur. ② Do not let errors slip past the “filters” to protect you. ③ Verbalize threats to the rest of the crew. 1 《 I N D E X 》 1. Preface 2. PARADIGM SHIFT Shift from “ James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model ” to “ Shigeru Fujii’s Japanese Rice Cracker Model ” 1.2 PPS (a)PPS concept (GENERAL) (b)PPS development (PARTICULARS) 2. Know where to look first 3. Case Study/Data acquisition 2 4. My Goal of PPS 4.1 PPS outside Cockpit 【Phase-1-A】 4.2 PPS inside Cockpit 4.2.1 PPS inside Cockpit with DARUMA 【Phase-1-B】 4.2.2 PPS inside Cockpit with ULTRAMAN 【Phase-2】 4.3 IDEAL PPS 【Phase-3】 5. Appendix 5.1 Aircraft manufactures strategy on runway incursion 5.1.1 Boeing runway safety strategy 3 5.2 James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management 5.3 Full transcript of Cockpit Voice Recorder of Comair 5191/27Aug,2006 6. Afterword 4 1. Preface PPS is “Proactive and Predictive System to mitigate/minimize/eliminate PICs fatal decision-making errors by Deep Learning AI”. PIC is a captain who is ultimately responsible for his flying aircraft operation and safety during the flight. “PICs fatal decision-making errors” are, naturally speaking, made by PICs.