Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron's Letters

The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters Michel Briand To cite this version: Michel Briand. The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters. The Letters of Alciphron : To Be or not To be a Work ?, Jun 2016, Nice, France. hal-02522826 HAL Id: hal-02522826 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02522826 Submitted on 27 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE GIRLFRIENDS’ LETTERS: POIKILIA IN THE BOOK 4 OF ALCIPHRON’S LETTERS Michel Briand Alciphron, an ambivalent post-modern Like Lucian of Samosata and other sophistic authors, as Longus or Achilles Tatius, Alciphron typically represents an ostensibly post-classical brand of literature and culture, which in many ways resembles our post- modernity, caught in permanent tension between virtuoso, ironic, critical, and distanced meta-fictionality, on the one hand, and a conscious taste for outspoken and humorous “bad taste”, Bakhtinian carnavalesque, social and moral margins, convoluted plots and sensational plays of immersion and derision, or realism and artificiality: the way Alciphron’s collection has been judged is related to the devaluation, then revaluation, the Second Sophistic was submitted to, according to inherently aesthetical and political arguments, quite similar to those with which one often criticises or defends literary, theatrical, or cinematographic post- 1 modernity. -

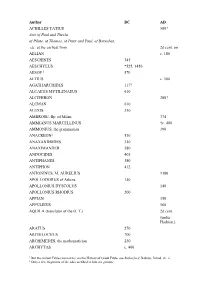

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Gostin Front

Excerpted from © by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. May not be copied or reused without express written permission of the publisher. click here to BUY THIS BOOK Introduction I The early Alexandrian period under the first three Ptolemies (ca. 300–221 b.c.e.) saw not only an awakened interest in the preservation and classification of earlier Greek poetry but also a desire to refashion, even reinvent, many centuries-old types of poetry in a new cultural and geographical setting. The poets of this period composed hymns, epini- cians, and epigrams, to mention only a few genres, which, while often recalling earlier literary models through formal imitation and verbal allusion, at the same time exhibit marked variation and innovation, whether in the assembling of generic features, in disparities of tone, or in choice of theme or emphasis. This memorialization of earlier art forms calls attention both to the poetic models, their authors, and their artistic traditions, and also to the act of memorialization itself, the poet, and his own place in that same poetic tradition. Some of these genres that the poets in early Ptolemaic Alexandria took up are known to have had a continuous life on the Greek main- land and elsewhere in the Greek-speaking world. Others had fallen into disuse already by the fifth century, but were now revived in Alexandria for a new audience, one of cosmopolitan nature and attached to a royal court and its institutions, including the Mouseion. Among these latter genres was iambos, a genre of stichic poetry recited to the aulos (oboe) and associated above all with Archilochus of Paros, Hipponax of Eph- esus, and the cultural milieu of seventh- and sixth-century Ionia.1 Iambic poetry of the archaic period is a genre that demonstrates tremendous variation and thus defies narrow or easy demarcation.2 In 1. -

Aristaenetus, Erotic Letters

ARISTAENETUS, EROTIC LETTERS Writings from the Greco-Roman World David Konstan and Johan C. Thom, General Editors Editorial Board Erich S. Gruen Wendy Mayer Margaret M. Mitchell Teresa Morgan Ilaria L. E. Ramelli Michael J. Roberts Karin Schlapbach James C. VanderKam L. Michael White Number 32 Volume Editor Patricia A. Rosenmeyer ARISTAENETUS, EROTIC LETTERS Introduced, translated and annotated by Peter Bing and Regina Höschele Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta ARISTAENETUS, EROTIC LETTERS Copyright © 2014 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aristaenetus, author. Erotic letters / Aristaenetus ; introduced, translated, and annotated by Peter Bing and Regina Höschele. pages cm. — (Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; volume 32) ISBN 978-1-58983-741-6 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-742-3 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-882-6 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) 1. Aristaenetus. Love epistles. I. Bing, Peter. II. Höschele, Regina. III. Aristaenetus. Love epistles. English. 2013. IV. Series: Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; v. 32. PA3874.A3E5 2013 880.8'.03538—dc23 2013024429 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

Sexual Initiative in Aristaenetus' Erotic Letters

UDC: 305:176(38) REVIEWED: 04. 04. 2018; 05. 04. 2018 Sexual initiative in Aristaenetus’ Erotic Letters Sabira Hajdarević Department of Classical Philology University of Zadar, Croatia [email protected] ABSTRACT The epistolary collection entitled Erotic Letters attributed to Aristaenetus was probably written in the 6th century A.D. The letters depict various sexual liaisons; the protagonists are single, married, engaged in extra‐marital affairs, in relationships with slaves or courtesans etc. The focus of the research is on the overall representation of lovers’ sexuality. The author investigates which sex is more likely to show sexual interest, to seduce, to initiate foreplay or sexual activities and to create the opportunity for their achievement. The results are placed into a wider context by the comparison with gender relations in Alciphron’s, Aelian’s and Philostratus’ collections. The final goal of the paper is to point to (potential) differences in the representation of male and female sexual agency and sexuality in general throughout the literary subgenre from Alciphron to Aristaenetus. Key words: Aristaenetus, Greek sexuality, sexual initiative, Greek fictional epistolography Systasis 32 (2018) 1‐24 1 Sabira HAJDAREVIĆ –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1. Introduction Aristaenetus’ Erotic Letters belong to Greek fictional epistolography, a literary subgenre which fully blossomed in the 2nd and 3rd century A.D., during the times of Alciphron – its most successful representative – and Aelian and Philostratus. There is very little substantial evidence when and where all of the collections originated. In the case of Aristaenetus even the authorship is debatable,1 and the input from the text places it in the 6th century (Drago 2007, 25‐36). -

Acontius and Cydippe’ (Aetia FR.75.10-19 Harder)1

Callimachus and Hippocratic Gynecology Absent desire and the female body in ‘Acontius and Cydippe’ (Aetia FR.75.10-19 Harder)1 George Kazantzidis University of Johannesburg [email protected] In an important article published in 1992 Lesley Dean-Jones observes in ‘The Politics of Pleasure: Female Sexual Appetite in the Hippocratic Corpus’, that in early Greek medical writings a woman’s urge to have sex with a man, and the satisfaction she occasionally derives from it, are marked by the systematic absence of ‘conscious sexual desire’. That is, unlike men whose appetite for sex is normally stimulated by a specific object of desire (be it an actual object or its mental image), women are almost automatically compelled to have intercourse in order to replenish 1 — I wish to thank the anonymous referees of EuGeStA for their immensely helpful com- ments on the first draft of this article as well as audiences in Oxford, Reading and Prato, Italy, where this paper was delivered, especially: Philip Hardie, Angelos Chaniotis, Tim Whitmarsh, Gregory Hutchinson, Bob Cowan, Damien Nelis, Benjamin Acosta-Hughes and Aldo Setaioli. I would also like to express my warm thanks to Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides and Daniel Orrells, organisers of the splendid workshop ‘The Little Torch of Cypris: Gender and Sexuality in Hellenistic Alexandria and Beyond’ (Prato, Italy, 2-4 September 2013). EuGeStA - n°4 - 2014 CALLIMachUS AND Hippocratic GYnecologY 107 moisture in their bodies, facilitate menstruation and maintain physical balance internally. In Dean-Jones’ words, female sexual appetite, as des- cribed in Hippocratic gynecology, ‘precludes directed desire’ and, along with it, ‘the exercise of self-control over the body’s imperative to’ take part in ‘intercourse’2. -

Erotic Letters

Erotic Language and Representations of Desire in the Philostratean Erotic Letters Erotic Language and Representations of Desire in the Philostratean Erotic Letters Antonios Pontoropoulos Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska Teater, Thunbergsvägen 3 (Campus Engelska Parken), Uppsala, Saturday, 21 September 2019 at 14:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor (Dr.) Owen Hodkinson (University of Leeds, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies). Abstract Pontoropoulos, A. 2019. Erotic Language and Representations of Desire in the Philostratean Erotic Letters. 240 pp. Uppsala: Department of Linguistics and Philology, Faculty of Languages, Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-506-2781-7. This doctoral dissertation focuses on a corpus of seventy-three prose letters from the Imperial period, titled Erotic Letters and attributed to Philostratus. In this letter collection, different anonymous letter writers address male and female recipients who are mostly anonymous. I contextualize the Philostratean erotic discourse in terms of Greek Imperial literature and the rhetorical culture of the Second Sophistic. Unlike the letter corpora of Aelian and Alciphron, the Philostratean Letters take a strong interest in ancient pederasty. Furthermore, the ancient Greek novel provides a fruitful comparison for the study of this particular letter corpus. The Philostratean erotic discourse employs a series of etiquettes and erotic labels which trace back to earlier (classical or Hellenistic) periods of Greek literary history. In this sense, the Philostratean Erotic Letters situate themselves in a long-standing Greek erotic tradition and draw from the prestigious classical past. In the context of individual Philostratean letters, pederastic motifs are often employed in heterosexual narratives and subvert the expected erotic discourse. -

The Function of the Pellichus Sequence at Lucian Philopseudes 18-20

The Function of the Pellichus Sequence at Lucian Philopseudes 18-20 Daniel Ogden One of the more extended exchanges on magic and the supernatural between the host Eucrates and his guests in Lucian’s Philopseudes or Lover of lies is the sequence con cerning Eucrates’ own animated statue of Pellichus, which can dismount from its pedes tal, heal the sick, and punish the sacrilegious.* 1 This paper explores the multiple functions that that tale and the discussion surrounding it play within the dialogue.2 We will consider: the sequence’s positioning and structural function within the wider dialogue; the purpose of its ecphrastic elements; the manner in which Eucrates may be seen to unravel his own story as he tells it; Lucian’s commentary upon the phenomenon of heal ing statues; and finally the contextualisation of the sinister threats offered by the statue. First, the sequence itself, 18. ‘At any rate the statue business’, said Eucrates, ‘was witnessed night after night by the entire household, children, young and old alike. You could hear about this not just from me but also from the whole of our staff. ‘What sort of statue?’ said I. ‘Did you not notice that gorgeous statue erected in the hall as you came in, the work of the portrait-sculptor Demetrius?’ ‘You don’t mean the discus-thrower, do you’, I said, ‘the one bending into the throw ing position, turning back towards the hand with the discus, gently sinking on one leg, looking as if he is about to lift himself up for the throw?’ ‘No, not that one’, said he. -

Index Nominum

Index nominum Nombre d'enregistrements : 7617dont 1801 renvois Abad, Pierre. Aboul Moayyed Mohammed. Voir: Abbat, Per Auteur supposé : oeuvre traditionnellement classée au titre, cf. Abbadi, Mostafa El-. "Index des titres" 'Abbâs Khân Kakbûr Surwânî Ahmadî. Voir: Sîra 'Antar Voir: Abbâs Khân Sarvânî (fl. 1579) Abraham, Claude Kurt (1931). Abbâs Khân Sarvânî (fl. 1579). Abrahams, Roger D. (1933). Abbasi, Riza (XVIIe s.). Abramovici, Jean-Christophe. Abbat, Per. Abu 'Imrân Mûsâ. Abd al-Hamîd (VIIIe s.). Voir: Maimonides, Moses (1138-1204) Abd al-Rahîm al-Hawrânî. Abu al-'Ala' al-Ma'arrî, Ahmed Ibn 'Abd Allah (973-1058). Voir: Hawrânî, 'Abd al-Rahîm al-Dimasqî al- Abû al-Hasan, Sa'îd (al-Sirâfî). Abd al-Rahmâne al-Djawbarî. Voir: Hasan ibn Yazîd, Abû Zaid (al-Sirâfî) [fl. 920] Voir: Djawbarî, 'Abd al-Rahmâne al- Abû al-Mutahhar al-Azdî (fin XIe s.). Abd al-Rahmane. Abû Bakr ibn al-Tufail, Abû Jàfar al-Ishbîlî. Voir: Rahmane ibn Abi-Bakr al-Souyoûtî, 'Abd al- (1445-1505) Voir: Ibn Tufayl, Muhammad ben Abd-el-Malik el-Qaïçi (v. 1105 Abd ar-Rahmân al Mag'dûb 'Halifa, Bu'hârî. -1185) Voir: Majdhûb, Al- (1504- v. 1563) Abu Djafar. Abd-al-Kadir Guilânî. Abû Hayyân al-Tawhîdî. Voir: Abdul-Qâder al-Jilâni (1077-1166) Voir: Tawhîdî, 'Ali Ibn Muhammad Abû Hayyân al- (v. 922/32-v. 'Abdalghani an Nâbolosî. 1023/36) Voir: Nâbulusî, 'Abd al-Ganî Ibn Ismâîl (1641-1731) Abû Holayqa, Rasîd al-Dîn (m. 1277). Abdelamir, Chawki. Abû Hulayqa. Abdol Aziz (fl. 1560). Voir: Abû Holayqa, Rasîd al-Dîn (m. 1277) Abû l-'As (ibn 'Abd al-Wahhâb at-Taqafî) [IXe s.]. -

Alciphron, Letters of the Courtesans: Edited with Introduction, Translation and Commentary

ALCIPHRON LETTERS OF THE COURTESANS ALCIPHRON LETTERS OF THE COURTESANS EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION, TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY BY PATRIK GRANHOLM Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Engelska parken, Humanistiskt centrum, Thunbergsvägen 3, Uppsala, Saturday, December 15, 2012 at 14:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Granholm, P. 2012. Alciphron, Letters of the Courtesans: Edited with Introduction, Translation and Commentary. 265 pp. Uppsala. This dissertation aims at providing a new critical edition of the fictitious Letters of the Cour- tesans attributed to Alciphron (late 2nd or early 3rd century AD). The first part of the introduction begins with a brief survey of the problematic dating and identification of Alciphron, followed by a general overview of the epistolary genre and the letters of Alciphron. The main part of the introduction deals with the manuscript tradition. Eighteen manuscripts, which contain some or all of the Letters of the Courtesans, are described and the relationship between them is analyzed based on complete collations of all the manuscripts. The conclusion, which is illustrated by a stemma codicum, is that there are four primary manuscripts from which the other fourteen manuscripts derive: Vaticanus gr. 1461, Laurentianus gr. 59.5, Parisinus gr. 3021 and Parisinus gr. 3050. The introduction concludes with a brief chapter on the previous editions, a table illustrating the selection and order of the letters in the manuscripts and editions, and an outline of the editorial principles. The guiding principle for the constitution of the text has been to use conjectural emendation sparingly and to try to preserve the text of the primary manuscripts wherever possible. -

Imitation, Variation, Exploitation: a Study in Aristaenetus Arnott, W Geoffrey Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1973; 14, 2; Proquest Pg

Imitation, Variation, Exploitation: a Study in Aristaenetus Arnott, W Geoffrey Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1973; 14, 2; ProQuest pg. 197 Imitation, Variation, Exploitation: a Study in Aristaenetus w. Geoffrey Arnott R OTTO MAZAL'S new Teubner edition of Aristaenetus (Stutt D gart 1971) is to be welcomed on several accounts. It provides a satisfactory, perhaps slightly over-conservative text with a fully detailed critical apparatus and by its side a substantial list of those passages pillaged by the author in order to trick out his own second rate talents. Although the critical apparatus has its imperfections and the list of passages is neither complete nor differentiated according to the type of use made by Aristaenetus of his sources,! this edition ought to serve as a stimulus to future research on an author whose import ance depends more perhaps on his use of the Greek language, his accentually regulated clausulae,2 his exploitation of the writings of greater predecessors and a few tricks of technique than on the merits of any personal imaginative or stylistic genius. Among other desi derata, an exhaustive, careful study of his use of source material is very much needed. This paper investigates a few interesting and hitherto (so far as I know) uninvestigated techniques used by Aristaenetus 3 in the manipulation of his sources and in the presentation of his material. Sometimes Aristaenetus plagiarises verbatim or with minor amend ments phrases, sentences, even paragraphs from earlier authors. These are normally prose,