Dissertation Full Draft Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Meter

Introduction to Meter A stress or accent is the greater amount of force given to one syllable than another. English is a language in which all syllables are stressed or unstressed, and traditional poetry in English has used stress patterns as a fundamental structuring device. Meter is simply the rhythmic pattern of stresses in verse. To scan a poem means to read it for meter, an operation whose noun form is scansion. This can be tricky, for although we register and reproduce stresses in our everyday language, we are usually not aware of what we’re going. Learning to scan means making a more or less unconscious operation conscious. There are four types of meter in English: iambic, trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic. Each is named for a basic foot (usually two or three syllables with one strong stress). Iambs are feet with an unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable. Only in nursery rhymes to do we tend to find totally regular meter, which has a singsong effect, Chidiock Tichborne’s poem being a notable exception. Here is a single line from Emily Dickinson that is totally regular iambic: _ / │ _ / │ _ / │ _ / My life had stood – a loaded Gun – This line serves to notify readers that the basic form of the poem will be iambic tetrameter, or four feet of iambs. The lines that follow are not so regular. Trochees are feet with a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. Trochaic meter is associated with chants and magic spells in English: / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Double, double, toil and trouble, / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Fire burn and cauldron bubble. -

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry Paul Kiparsky Stanford University [email protected] Linguistics Department, Stanford University, CA. 94305-2150 July 19, 2009 Review (4872 words) The publication of this joint book by the founder of generative metrics and a distinguished literary linguist is a major event.1 F&H take a fresh look at much familiar material, and introduce an eye-opening collection of metrical systems from world literature into the theoretical discourse. The complex analyses are clearly presented, and illustrated with detailed derivations. A guest chapter by Carlos Piera offers an insightful survey of Southern Romance metrics. Like almost all versions of generative metrics, F&H adopt the three-way distinction between what Jakobson called VERSE DESIGN, VERSE INSTANCE, and DELIVERY INSTANCE.2 F&H’s the- ory maps abstract grid patterns onto the linguistically determined properties of texts. In that sense, it is a kind of template-matching theory. The mapping imposes constraints on the distribution of texts, which define their metrical form. Recitation may or may not reflect meter, according to conventional stylized norms, but the meter of a text itself is invariant, however it is pronounced or sung. Where F&H differ from everyone else is in denying the centrality of rhythm in meter, and char- acterizing the abstract templates and their relationship to the text by a combination of constraints and processes modeled on Halle/Idsardi-style metrical phonology. F&H say that lineation and length restrictions are the primary property of verse, and rhythm is epiphenomenal, “a property of the way a sequence of words is read or performed” (p. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Lerud Dissertation May 2017

ANTAGONISTIC COOPERATION: PROSE IN AMERICAN POETRY by ELIZABETH J. LERUD A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Elizabeth J. LeRud Title: Antagonistic Cooperation: Prose in American Poetry This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the English Department by: Karen J. Ford Chair Forest Pyle Core Member William Rossi Core Member Geri Doran Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017. ii © 2017 Elizabeth J. LeRud iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Elizabeth J. LeRud Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2017 Title: Antagonistic Cooperation: Prose in American Poetry Poets and critics have long agreed that any perceived differences between poetry and prose are not essential to those modes: both are comprised of words, both may be arranged typographically in various ways—in lines, in paragraphs of sentences, or otherwise—and both draw freely from the complete range of literary styles and tools, like rhythm, sound patterning, focalization, figures, imagery, narration, or address. Yet still, in modern American literature, poetry and prose remain entrenched as a binary, one just as likely to be invoked as fact by writers and scholars as by casual readers. I argue that this binary is not only prevalent but also productive for modern notions of poetry, the root of many formal innovations of the past two centuries, like the prose poem and free verse. -

The Cambridge Companion to Modern Irish Culture Edited by Joe Cleary, Claire Connolly Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-52629-6 — The Cambridge Companion to Modern Irish Culture Edited by Joe Cleary, Claire Connolly Index More Information Index Aalto, Alvar, 286, 295–6 Daniel O’Connell’s strategy, 30 Abbey Theatre, 326–31 Politics and Society in Ireland, 1832–1885, see also Deevey, Teresa; Dublin Trilogy by 29–30 Sean O’Casey; Yeats, W. B. flexibility of Gladstone’s politics, 32–3 Casadh an tSug´ ain´ , 327, 328 implications of Home Rule, and colonial administration, 329 32–3 Lionel Pilkington’s observations on, W. E. Vaughan on advanced reforms 329 and, 31–2 The Shewing Up of Blanco Posnet, 329 relation to Belfast Agreement, 39–40 Gabriel Fallon’s comments on tradition Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland, of, 332–3 The, 310 George Russell on creation of medieval administration, colonial. See colonial theatre, 327–8 administration and theatre new building for by Michael Scott, 333 Adorno, Theodor, 168 Playboy of the Western World, 328–9 affiliation, religious, see power and religious as state theatre, 329–31 affiliation Thompson in Tir-na-nOg´ ,328 Agreement, Belfast. See Belfast Agreement Abhrain´ Gradh´ Chuige´ Chonnacht. See Love-Songs Agreement, Good Friday, 199–200 of Connacht All Souls’ Day,221 abortion alternative enlightenment, 5–6 Hush-a-Bye-Baby,217–18 America, United States of. See race, ethnicity, The Kerry Babies’ case, 218 nationalism and assimilation About Adam,221–2 Amhran´ na Leabhar,272 Absentee, The,255 Amongst Women,263 assimilation, cultural, 49 An Beal´ Bocht, 250 Academy, Royal Hibernian, -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Rhythm and Meter in Macbeth Iambic Pentameter (Nobles)

Grade 9 Analysis- Rhythm and Meter in Macbeth Iambic Pentameter (Nobles) What is it? Shakespeare's sonnets are written predominantly in a meter called iambic pentameter, a rhyme scheme in which each sonnet line consists of ten syllables. The syllables are divided into five pairs called iambs or iambic feet. An iamb is a metrical unit made up of one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable. An example of an iamb would be good BYE. A line of iambic pentameter flows like this: baBOOM / baBOOM / baBOOM / baBOOM / baBOOM. Why does Shakespeare use it? When Shakespeare's characters speak in verse (iambic pentameter), they are usually the noble (aristocratic) characters, and their speech represents their high culture and position in society. It gives the play a structured consistency, and when this is changed in instances of prose such as when Macbeth writes to Lady Macbeth and when Lady Macduff talks with her son, these are normally instances where a situation is abnormal e.g. when the Porter babbles in his drunken haze. Trochaic Tetrameter (Witches) What is it? Trochaic tetrameter is a rapid meter of poetry consisting of four feet of trochees. A trochee is made up of one stressed syllable followed by one unstressed syllable (the opposite of an iamb). Here is the flow of a line of trochaic tetrameter: BAboom / BAboom / BAboom / BAboom. Why does Shakespeare use it? The witches’ speech patterns create a spooky mood from the start of the scene. Beginning with the second line, they speak in rhyming couplets of trochaic tetrameter. The falling rhythm and insistent rhyme emphasize the witchcraft they practice while they speak—boiling some sort of potion in a cauldron. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

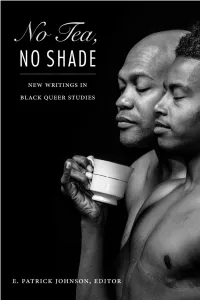

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There

English 201 Major British Authors Harris Reading Guide: Forms There are two general forms we will concern ourselves with: verse and prose. Verse is metered, prose is not. Poetry is a genre, or type (from the Latin genus, meaning kind or race; a category). Other genres include drama, fiction, biography, etc. POETRY. Poetry is described formally by its foot, line, and stanza. 1. Foot. Iambic, trochaic, dactylic, etc. 2. Line. Monometer, dimeter, trimeter, tetramerter, Alexandrine, etc. 3. Stanza. Sonnet, ballad, elegy, sestet, couplet, etc. Each of these designations may give rise to a particular tradition; for example, the sonnet, which gives rise to famous sequences, such as those of Shakespeare. The following list is taken from entries in Lewis Turco, The New Book of Forms (Univ. Press of New England, 1986). Acrostic. First letters of first lines read vertically spell something. Alcaic. (Greek) acephalous iamb, followed by two trochees and two dactyls (x2), then acephalous iamb and four trochees (x1), then two dactyls and two trochees. Alexandrine. A line of iambic hexameter. Ballad. Any meter, any rhyme; stanza usually a4b3c4b3. Think Bob Dylan. Ballade. French. Line usually 8-10 syllables; stanza of 28 lines, divided into 3 octaves and 1 quatrain, called the envoy. The last line of each stanza is the refrain. Versions include Ballade supreme, chant royal, and huitaine. Bob and Wheel. English form. Stanza is a quintet; the fifth line is enjambed, and is continued by the first line of the next stanza, usually shorter, which rhymes with lines 3 and 5. Example is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. -

Hollow Men: Colonial Forms, Irish Subjects, and the Great Famine in Modernist Literature, 1890-1930

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2016 Hollow Men: Colonial Forms, Irish Subjects, and the Great Famine in Modernist Literature, 1890-1930 Aaron Matthew Percich Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Percich, Aaron Matthew, "Hollow Men: Colonial Forms, Irish Subjects, and the Great Famine in Modernist Literature, 1890-1930" (2016). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6399. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6399 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hollow Men: Colonial Forms, Irish Subjects, and the Great Famine in Modernist Literature, 1890-1930 Aaron Matthew Percich A dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English. Lisa Weihman, Ph.D., Chair Dennis W. Allen, Ph.D. Gwen Bergner, Ph.D. John B. Lamb, Ph.D. Enda Duffy, Ph.D. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg.