Long Memories and Short Fuses Change and Instability in the Balkans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World History Final Exam Review Guide

World History Final Exam Review Guide Name: ____________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Hour: ____ THIS IS A MANDATORY STUDY GUIDE WORTH 15 POINTS, DUE THE DAY OF YOUR EXAM. IT MUST BE HANDWRITTEN. My exam is on __________________________, June __________ at ______________ AM. Much like the midterm, the exam consists of reading text, maps, and charts that will be interpreted. The exam also includes facts, concepts, and patterns that pertain to the civilizations and events we studied. All exams are challenging; you will have to study for this exam to do well. Please start to prepare early. Twenty minutes a day will go a long way toward your performance on the exam. Imperialism 1. List three reasons the Europeans sought to colonize Africa. (pg 774-76) a. b. c. 2. What is Social Darwinism and how did it justify imperialism?(pg 775) 3. What is a sphere of influence and how did it impact European countries? (pg 807) 4. How did spheres of influence impact China? (pg 808) 5. What was the main cause of the Opium War? (pg 806) 6. How were the Sepoy Mutiny and the Boxer Rebellion similar? (pg 793) 7. Define cash crop and explain its impact on lands colonized by Europeans. (pg 776) 8. What was Japan’s official policy toward foreigners in the early 1800s? (pg 547, 810) 9. What benefits did India offer to Great Britain during Imperialism? (pg 791) 10. Which European leader was known for exploiting and killing natives during African imperialism? (pg 774) 11. What was established at the Berlin Conference? (pg 776) 12. -

European Security Forum a Joint Initiative of Ceps and the Iiss

EUROPEAN SECURITY FORUM A JOINT INITIATIVE OF CEPS AND THE IISS A EUROPEAN BALKANS? ESF WORKING PAPER NO. 18 JANUARY 2005 WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY JACQUES RUPNIK DANIEL SERWER BORIS SHMELEV SUMMING UP BY FRANÇOIS HEISBOURG ISBN 92-9079-532-8 © COPYRIGHT 2005, CEPS & IISS CENTRE FOR THE INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE EUROPEAN FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES POLICY STUDIES Place du Congrès 1 ▪ B-1000 Brussels, Belgium Arundel House ▪ 13-15 Arundel Street, Temple Place Tel: +32 (0)2.229.39.11 ▪ Fax: +32 (0)2.219.41.51 London WC2R 3DX, United Kingdom www.ceps.be ▪ E-mail: [email protected] Tel. +44(0)20.7379.7676 ▪ Fax: +44(0)20.7836.3108 www.iiss.org ▪ E-mail: [email protected] A European Balkans? Working Paper No. 18 of the European Security Forum Contents Chairman’s Summing up FRANÇOIS HEISBOURG 1 Europe’s Challenges in the Balkans A European Perspective JACQUES RUPNIK 4 Kosovo Won’t Wait An American Perspective DANIEL SERWER 7 The Balkans: Powder keg of Europe or Zone of Peace and Stability? A Russian Perspective BORIS SHMELEV 13 Chairman’s Summing up François Heisbourg* he Chairman recalled the reasons for holding this particular session. On the one hand, at the Thessaloniki meeting of the European Council (June 2003), the prospect was Tlaid out of the Balkans being included, over time, within the European Union; hence, the title of the session. How that vision is to be fulfilled is obviously very much open to question, which is indeed one of reasons underlying the work of the new International Commission on the Balkans chaired by former Italian Prime Minister Giuliano Amato. -

Reconciliation Without Forgiveness: the EU in Promoting Postwar Cooperation in Serbia and Kosovo

Reconciliation without Forgiveness: The EU in Promoting Postwar Cooperation in Serbia and Kosovo Alexander Whan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in International Studies: Russian, Eastern European, Central Asian Studies University of Washington 2016 Committee: Christopher Jones Scott Radnitz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies 2 ©Copyright 2016 Alexander Whan 3 University of Washington Abstract Reconciliation without Forgiveness: The EU in Promoting Postwar Cooperation in Serbia and Kosovo Alexander Whan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Christopher Jones International Studies This paper examines the role and depth of interstate reconciliation in the postwar relationship between Serbia and Kosovo via their interactions with the European Union. Examined within this paper are models of interstate reconciliation, historical examples of this phenomenon, and the unique position that the European Union holds in terms of its leverage over both countries. Provided first in the paper is a section dealing with the historical importance of Kosovo within Serbian national mythology, the gradual deterioration of ethnic relations during the breakup of Yugoslavia, the eventual outbreak of war and Kosovo's independence, and the subsequent normalization of ties between Belgrade and Pristina. The paper continues to examine several different scholarly frameworks for defining and identifying the concept of interstate reconciliation—that is, its meaning, its components, and its processes—and synthesize them into a useable model for the Serbia-Kosovo relationship. Explored further are the historical cases of post-World War II Germany/Poland, Japan/China, and Turkey/Armenia as precedents for future reconciliation. -

World War I Begins 4 Long-Term Causes of WWI 1. Nationalism

Ch 11 The First World War Section 1: World War I Begins 4 Long-term Causes of WWI 1. Nationalism – the belief that national interests and national unity should be placed ahead of global cooperation and a nation’s foreign affairs should be guided by its own self-interest a. France – jockeying for European leadership, still recovering from land losses during the Franco-Prussian War b. Germany – created after the Prussian victory over France, competing with France for European power c. Russia – protector of Europe’s Slavic peoples d. Serbia – independent nation e. Austria-Hungary – rival with Russia for influence over Serbia 2. Imperialism - as Germany industrialized, it competed with France and Britain in the contest for colonies 3. Militarism – development of armed forces and their use as a tool of diplomacy a. By 1890, Germany was the strongest European nation b. Had an army reserve system and a strong navy 4. Alliance System – mutual hostilities, jealousies, fears, and desires led European nations to sign alliances a. Two major alliances by 1914 1. Allies (Triple Entente) – France, Great Britain, and Russia (also has a separate treaty with Serbia) 2. Central Powers (Triple Alliance) – Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy (joins allies in 1915), and the Ottoman Empire b. Provided a measure of international security Assassination Leads to War 1. Balkan Peninsula – bounded by the Black Sea, Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and the Aegean Sea (Powder Keg of Europe) a. Russia – wanted an outlet to the Mediterranean b. Germany – extend RRs to Ottoman Empire c. Austria-Hungary – annexed Bosnia in 1908, objected to Serbia encouraging Bosnians to reject Austria-Hungary rule 2. -

The Powder Keg of Europe Before WWI

The Powder Keg of Europe Before WWI The Balkans, for most of its history, has been attacked and colonized by outside forces. Alexander the Great of Macedonia took control of the region in 335 B.C, followed by the Roman’s in the 3rd century A.D. The last colonizing force was the Ottoman Empire from the 15th to the 19th century A.D. Despite all the invaders who have conquered the region, the area has still managed to obtain their own separate languages and identity. When the Ottoman Empire lost control of the Balkan region in the late 1800s after being defeated in battle by Russia, the Balkan region decided this was the opportunity to fight for independence. In 1908 Austria-Hungary infuriated many Balkan states by claiming Bosnia for themselves. Between 1912 and 1913 the Balkan league successfully claimed territory in battle from the Ottomans to unite the Balkan region. Bosnia however was still not part of the united Balkans, and this incited neighboring Serbia’s nationalism. Nationalist Serbia was part of the Pan-Slavic Movement, which contributed to the tension in the region. The goal of the movement was to unite the southern European Slavs into one Slavic nation. The Pan-Slavic Movement was heavily supported by Russia, who felt a strong connection to the Slavs of south eastern Europe due to their shared culture. Additionally, Serbia was now surrounded by Austria-Hungary and therefore vulnerable to invasion. When Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, announced a tour was to be commenced on the 28th of June in Sarajevo, Bosnia’s largest city, an opportunity presented itself for a nationalist Slavic group. -

The Chronicle of the First World War and Its Impact on the Balkans Birinci Dünya Savaşı’Nın Tarihi Ve Balkanlar’A Etkisi

The Chronicle Of The First World War And Its Impact On The Balkans Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nın Tarihi ve Balkanlar’a Etkisi Erjada Progonati* Abstract The process of the two Balkan Wars (1912-1913) remained incomplete until the First World War started. The aim of this study is to give some informations about The First World War and the role that Balkan region played to this war when the national consciousness of Balkan peoples began to crystallize. After the two Balkan Wars, all the Balkan states continued their efforts to gather their co-nationals into their national states. It’s concluded that the Balkan Wars leaded to the internationalization of this crisis spreading it to an ample area while many other crises at the same region were resolved without a general war in Europe. It appears that the First World War that began in 1914 in the Balkan region was a continuation of the wars that started in 1912-1913 period in the same are. Key Words: World War I, Balkans, Nationalism, Balkan Wars, History. Özet İki Balkan Savaşı (1912-1913) süreci, Birinci Dünya Savaşı başlayana dek eksik kalmıştır. Bu çalış- manın amacı, Birinci Dünya Savaşı ve ulusal bilinçlerin belirginleşmeye başlayan Balkan halklarının savaşta oynadığı roller hakkında bazı bilgiler vermektir. İki Balkan Savaşlarından sonra bütün Balkan devletleri ulus-devletlerine ortak vatandaşlarını toplamak için çabalarını sürdürmüştür. Aynı bölgede birçok krizin Avrupa’da genel bir savaşa götürmeden çözüme kavuşurken Balkan Savaşları bu durumu daha geniş bir alana yayarak krizin uluslararasılaşmasına yol açtığı sonucuna varılmaktadır. 1914 yı- lında ve Balkanlar bölgesinde başlayan Birinci Dünya Savaşı, aynı bölgede ve 1912-1913 döneminde yaşanan savaşların devamı niteliğinde olduğu düşünülmektedir. -

The Balkans: Still the “Powder Keg” of Europe?

The Balkans: still the “powder keg” of Europe? Anita Szirota* Security Policy Officer at the Ministry of Interior of Hungary * Edited and updated by Dr Alessandro Politi. NATO Defense College Foundation Paper Abstract The Balkan region is one of the most ethnically, linguistically, religiously complex areas of the world. In the past decade all the countries of the region have experienced a period of transition and ethnic conflict with a decline in the standard of living and a slowing of economic growth; yet they have achieved different levels of democratisation. Although, there have been several attempts by the international community to consolidate the region, they have only been partially successful. It is reasonable to think whether the region is still the “powder keg” of Europe. Keywords: Balkans; security; conflicts; fragmentation; civil society; instability; regional cooperation. Introduction The dissolution of the Communist regimes gave rise to new political institution and provided a pathway for the rise of independent nation states. However, this transformation was not smooth and without obstacles. Countries of the region faced a triple transition from war to peace, from Socialism to democracy and market economy and from humanitarian aid to sustainable development. This is not comparable with any of the Central or Eastern European experience. Moreover, most of the regime changes were accompanied by serious ethnic uprisings and bloody wars. This paper aims to provide a brief overlook about the contemporary security challenges, emerged after the collapse of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Besides the obstacles of regime changes, the security environment has often been highly unstable in the Balkan countries. -

World War I Begins

WORLD WAR I BEGINS Unit 6: WWI Causes of the War M.A.I.N. Militarism Alliances Imperialism Nationalism (+ Balkan “Powder Keg”) Causes of the War ◦ Militarism – aggressive ◦ Imperialism preparation for war ◦ Scramble for Africa created tension between powers ◦ Industrialization allowed for larger armies and navies; new ◦ The “Eastern question” weapons ◦ Ottoman Empire began to shrink; European powers ◦ Conscription: military draft wanted their Balkan territory ◦ Extensive plans for mobilization (preparing and ◦ Nationalism organizing troops for active ◦ Ethnic groups without a nation service) dreamt of creating one ◦ Alliances ◦ Triple Alliance, Triple Entente Alliances ◦Triple Entente ◦ Russia, France, Britain ◦Triple Alliance ◦ Italy, Austria-Hungary, Germany ◦Russia also supported Serbia ◦Ottoman Empire also supported Germany The “Eastern Question” ◦ Ottoman Empire at risk of collapse in early 1900s ◦ Began to withdraw from its territory in Balkans ◦ Balkan region valuable because of location ◦ Between Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Russian Empire ◦ Had direct access to Mediterranean ◦ Balkans = volatile ◦ Intense nationalistic, ethnic conflict ◦ “Powder keg” The Balkans ◦ Serbia wanted to unite Slavs (ethnic group from E. Europe) ◦ Opposed by Austria-Hungary ◦ Ruled a large Slav population; threat of revolt ◦ Supported by Russia ◦ Most Russians are Slavs ◦ Russia despised Aus-Hun; wanted a Slav revolt ◦ Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina to prevent Serbia from uniting Slavs there ◦ June 1914 Archduke Franz Ferdinand -

The Western Balkans in the Transatlantic Security Context: Where Do We Go from Here?

ARTICLE OYA DURSUN-ÖZKANCA ARTICLES The Western Balkans in the Transatlantic Russia in the Balkans: Great Power Politics Security Context: Where Do We Go from Here? and Local Response OYA DURSUN-ÖZKANCA VSEVOLOD SAMOKHVALOV Prospects for Trilateral Relations between Turkey and Germany in the Balkans: Turkey, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina Competing with Each Other? MUHIDIN MULALIC ELİF NUROĞLU and HÜSEYİN H. NUROĞLU Albanian Slide: The Roots to NATO’s Pending Turkey and Saudi Arabia as Theo-political Lost Balkan Enterprise Actors in the Balkans: The Case of Bulgaria ISA BLUMI İSMAİL NUMAN TELCİ and AYDZHAN YORDANOVA PENEVA (Ir)relevance of Croatian Experience for Further EU Enlargement SENADA ŠELO ŠABIĆ 106 Insight Turkey THE WESTERN BALKANS ARTICLEIN THE TRANSATLANTIC SECURITY CONTEXT: WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? The Western Balkans in the Transatlantic Security Context: Where Do We Go from Here? OYA DURSUN-ÖZKANCA* ABSTRACT The Western Balkans has traditionally held vital geostrategic im- portance for European and transatlantic security. Ever since the 1990s, the EU and the NATO have maintained an active presence in the region, and pursued goals of stability and peace. Since the 2000s, the Euro-Atlantic actors have sought an eventual integration of the countries in the region into transatlantic structures. This article provides a comprehensive anal- ysis of the contemporary situation in the Western Balkans, examining the regional countries’ prospects for Euro-Atlantic integration and the impli- cations of the latest developments for transatlantic security. It makes the argument that NATO accession acts as a prelude to eventual EU accession, ensuring that the countries stay the course of engaging in reforms and con- tributing to Euro-Atlantic security while confirming their commitment to democracy. -

Militarism Militarism Is the Belief That a Country Should Have a Strong Military Capability and Be Prepared to Use It Aggressively to Defend Or Promote Its Interests

Militarism Militarism is the belief that a country should have a strong military capability and be prepared to use it aggressively to defend or promote its interests. Leading up to World War I, imperial countries in Europe were strong proponents of militarism. They spent more and more money on military technology, employing more troops, and training their soldiers. They found that to gain colonies it helped to be militarily superior to the people they colonized and the other industrialized countries they were competing with. As tensions in Europe increased leading up to 1914, European countries raised and prepared large armies, navies, and airforces to protect their homelands. German planes used in WWI. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AlbatDIII.jpg A battleship squadron of the German High Seas Fleet; the far right vessel is a member of the Kaiser class.1 917. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hochsee┄otte_2.jpg 3 Imperialism European countries competed with each other all over the world in the 1800s and early 1900s. They fought one another at sea and used treaty negotiations to claim colonies and spheres of in┄uence in Africa and Asia. The search for raw materials to fuel industry and markets to buy goods in far-┄ung corners of the world led to increased tension in Europe. Image to the right: A French political cartoon from 1898. "China -- the cake of kings and... of emperors" (a French pun on king cake and kings and emperors wishing to "consume" China). A pastry represents "Chine" (French for China ) and is being -

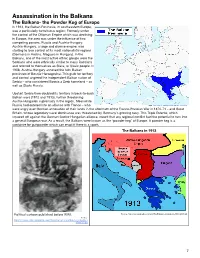

Assassination in the Balkans

Assassination in the Balkans The Balkans- the Powder Keg of Europe In 1914, the Balkan Peninsula, in southeastern Europe, was a particularly tumultuous region: Formerly under the control of the Ottoman Empire which was declining in Europe, the area was under the in粡uence of two competing powers, Russia and Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary, a large and diverse empire, was starting to lose control of its most nationalistic regions (Germans in Austria, Magyars in Hungary). In the Balkans, one of the most active ethnic groups were the Serbians who were ethnically similar to many Russians and referred to themselves as Slavs, or Slavic people. In 1908, Austria-Hungary annexed the twin Balkan provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina. This grab for territory and control angered the independent Balkan nation of Serbia – who considered Bosnia a Serb homeland – as well as Slavic Russia. Upstart Serbia then doubled its territory in back-to-back Balkan wars (1912 and 1913), further threatening Austro-Hungarian supremacy in the region. Meanwhile, Russia had entered into an alliance with France – who were angry over German annexation of their lands in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71 – and Great Britain, whose legendary naval dominance was threatened by Germany’s growing navy. This Triple Entente, which squared o against the German-Austro-Hungarian alliance, meant that any regional con粡ict had the potential to turn into a general European war. As a result, the Balkans were known as the “powder keg” of Europe. A powder keg is a container for gunpowder which can erupt if there is a spark. -

The Powder Keg of Europe Before WWI

The Powder Keg of Europe Before WWI The Balkans, for most of its history, has been attacked and colonized by outside forces. Alexander the Great of Macedonia took control of the region in 335 B.C, followed by the Roman’s in the 3rd century A.D. The last colonizing force was the Ottoman Empire from the 15th to the 19th century A.D. Despite all the invaders who have conquered the region, the area has still managed to obtain their own separate languages and identity. When the Ottoman Empire lost control of the Balkan region in the late 1800s after being defeated in battle by Russia, the Balkan region decided this was the opportunity to fight for independence. In 1908 Austria-Hungary infuriated many Balkan states by claiming Bosnia for themselves. Between 1912 and 1913 the Balkan league successfully claimed territory in battle from the Ottomans to unite the Balkan region. Bosnia however was still not part of the united Balkans, and this incited neighboring Serbia’s nationalism. Nationalist Serbia was part of the Pan- Slavic Movement, which contributed to the tension in the region. The goal of the movement was to unite the southern European Slavs into one Slavic nation. The Pan-Slavic Movement was heavily supported by Russia, who felt a strong connection to the Slavs of south eastern Europe due to their shared culture. Additionally, Serbia was now surrounded by Austria- Hungary and therefore vulnerable to invasion. When Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, announced a tour was to be commenced on the 28th of June in Sarajevo, Bosnia’s largest city, an opportunity presented itself for a nationalist Slavic group.