Mol of Solute Molality ( ) = Kg Solvent M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reverse Osmosis Bibliography Additional Readings

8/24/2016 Osmosis AccessScience from McGrawHill Education (http://www.accessscience.com/) Osmosis Article by: Johnston, Francis J. Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Publication year: 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/10978542.478400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/10978542.478400) Content Osmotic pressure Reverse osmosis Bibliography Additional Readings The transport of solvent through a semipermeable membrane separating two solutions of different solute concentration. The solvent diffuses from the solution that is dilute in solute to the solution that is concentrated. The phenomenon may be observed by immersing in water a tube partially filled with an aqueous sugar solution and closed at the end with parchment. An increase in the level of the liquid in the solution results from a flow of water through the parchment into the solution. The process occurs as a result of a thermodynamic tendency to equalize the sugar concentrations on both sides of the barrier. The parchment permits the passage of water, but hinders that of the sugar, and is said to be semipermeable. Specially treated collodion and cellophane membranes also exhibit this behavior. These membranes are not perfect, and a gradual diffusion of solute molecules into the more dilute solution will occur. Of all artificial membranes, a deposit of cupric ferrocyanide in the pores of a finegrained porcelain most nearly approaches complete semipermeability. The walls of cells in living organisms permit the passage of water and certain solutes, while preventing the passage of other solutes, usually of relatively high molecular weight. These walls act as selectively permeable membranes, and allow osmosis to occur between the interior of the cell and the surrounding media. -

Solutes and Solution

Solutes and Solution The first rule of solubility is “likes dissolve likes” Polar or ionic substances are soluble in polar solvents Non-polar substances are soluble in non- polar solvents Solutes and Solution There must be a reason why a substance is soluble in a solvent: either the solution process lowers the overall enthalpy of the system (Hrxn < 0) Or the solution process increases the overall entropy of the system (Srxn > 0) Entropy is a measure of the amount of disorder in a system—entropy must increase for any spontaneous change 1 Solutes and Solution The forces that drive the dissolution of a solute usually involve both enthalpy and entropy terms Hsoln < 0 for most species The creation of a solution takes a more ordered system (solid phase or pure liquid phase) and makes more disordered system (solute molecules are more randomly distributed throughout the solution) Saturation and Equilibrium If we have enough solute available, a solution can become saturated—the point when no more solute may be accepted into the solvent Saturation indicates an equilibrium between the pure solute and solvent and the solution solute + solvent solution KC 2 Saturation and Equilibrium solute + solvent solution KC The magnitude of KC indicates how soluble a solute is in that particular solvent If KC is large, the solute is very soluble If KC is small, the solute is only slightly soluble Saturation and Equilibrium Examples: + - NaCl(s) + H2O(l) Na (aq) + Cl (aq) KC = 37.3 A saturated solution of NaCl has a [Na+] = 6.11 M and [Cl-] = -

Parametrisation in Electrostatic DPD Dynamics and Applications

Parametrisation in electrostatic DPD Dynamics and Applications E. Mayoraly and E. Nahmad-Acharz February 19, 2016 y Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares, Carretera M´exico-Toluca S/N, La Marquesa Ocoyoacac, Edo. de M´exicoC.P. 52750, M´exico z Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, Universidad Nacional Aut´onomade M´exico, Apartado Postal 70-543, 04510 M´exico DF, Mexico abstract A brief overview of mesoscopic modelling via dissipative particle dynamics is presented, with emphasis on the appropriate parametrisation and how to cal- culate the relevant parameters for given realistic systems. The dependence on concentration and temperature of the interaction parameters is also considered, as well as some applications. 1 Introduction In a colloidal dispersion, the stability is governed by the balance between Van der Waals attractive forces and electrostatic repulsive forces, together with steric mechanisms. Being able to model their interplay is of utmost importance to predict the conditions for colloidal stability, which in turn is of major interest in basic research and for industrial applications. Complex fluids are composed typically at least of one or more solvents, poly- meric or non-polymeric surfactants, and crystalline substrates onto which these surfactants adsorb. Neutral polymer adsorption has been extensively studied us- ing mean-field approximations and assuming an adsorbed polymer configuration of loops and tails [1,2,3,4]. Different mechanisms of adsorption affecting the arXiv:1602.05935v1 [physics.chem-ph] 18 Feb 2016 global -

Molarity Versus Molality Concentration of Solutions SCIENTIFIC

Molarity versus Molality Concentration of Solutions SCIENTIFIC Introduction Simple visual models using rubber stoppers and water in a cylinder help to distinguish between molar and molal concentrations of a solute. Concepts • Solutions • Concentration Materials Graduated cylinder, 1-L, 2 Water, 2-L Rubber stoppers, large, 12 Safety Precautions Watch for spills. Wear chemical splash goggles and always follow safe laboratory procedures when performing demonstrations. Procedure 1. Tell the students that the rubber stoppers represent “moles” of solute. 2. Make a “6 Molar” solution by placing six of the stoppers in a 1-L graduated cylinder and adding just enough water to bring the total volume to 1 liter. 3. Now make a “6 molal” solution by adding six stoppers to a liter of water in the other cylinder. 4. Remind students that a kilogram of water is about equal to a liter of water because the density is about 1 g/mL at room temperature. 5. Set the two cylinders side by side for comparison. Disposal The water may be flushed down the drain. Discussion Molarity, moles of solute per liter of solution, and molality, moles of solute per kilogram of solvent, are concentration expressions that students often confuse. The differences may be slight with dilute aqueous solutions. Consider, for example, a dilute solution of sodium hydroxide. A 0.1 Molar solution consists of 4 g of sodium hydroxide dissolved in approximately 998 g of water, while a 0.1 molal solution consists of 4 g of sodium hydroxide dissolved in 1000 g of water. The amount of water in both solutions is virtually the same. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

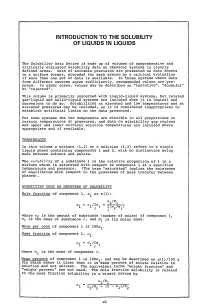

Introduction to the Solubility of Liquids in Liquids

INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLUBILITY OF LIQUIDS IN LIQUIDS The Solubility Data Series is made up of volumes of comprehensive and critically evaluated solubility data on chemical systems in clearly defined areas. Data of suitable precision are presented on data sheets in a uniform format, preceded for each system by a critical evaluation if more than one set of data is available. In those systems where data from different sources agree sufficiently, recommended values are pro posed. In other cases, values may be described as "tentative", "doubtful" or "rejected". This volume is primarily concerned with liquid-liquid systems, but related gas-liquid and solid-liquid systems are included when it is logical and convenient to do so. Solubilities at elevated and low 'temperatures and at elevated pressures may be included, as it is considered inappropriate to establish artificial limits on the data presented. For some systems the two components are miscible in all proportions at certain temperatures or pressures, and data on miscibility gap regions and upper and lower critical solution temperatures are included where appropriate and if available. TERMINOLOGY In this volume a mixture (1,2) or a solution (1,2) refers to a single liquid phase containing components 1 and 2, with no distinction being made between solvent and solute. The solubility of a substance 1 is the relative proportion of 1 in a mixture which is saturated with respect to component 1 at a specified temperature and pressure. (The term "saturated" implies the existence of equilibrium with respect to the processes of mass transfer between phases) • QUANTITIES USED AS MEASURES OF SOLUBILITY Mole fraction of component 1, Xl or x(l): ml/Ml nl/~ni = r(m.IM.) '/. -

Solute Concentration: Molality

5/25/2012 Colligative Properties of Solutions . Colligative Properties: • Solution properties that depend on concentration of solute particles, not the identity of particles. Previous example: vapor pressure lowering. Consequences: change in b.p. and f.p. of solution. © 2012 by W. W. Norton & Company Solute Concentration: Molality . Changes in boiling point/freezing point of solutions depends on molality: moles of solute m kg of solvent • Preferred concentration unit for properties involving temperature changes because it is independent of temperature. © 2012 by W. W. Norton & Company 1 5/25/2012 Calculating Molality Starting with: a) Mass of solute and solvent. b) Mass of solute/ volume of solvent. c) Volume of solution. © 2012 by W. W. Norton & Company Sample Exercise 11.8 How many grams of Na2SO4 should be added to 275 mL of water to prepare a 0.750 m solution of Na2SO4? Assume the density of water is 1.000 g/mL. © 2012 by W. W. Norton & Company 2 5/25/2012 Boiling-Point Elevation and Freezing-Point Depression . Boiling Point Elevation (ΔTb): • ΔTb = Kb∙m • Kb = boiling point elevation constant of solvent; m = molality. Freezing Point Depression (ΔTf): • ΔTf = Kf∙m • Kf = freezing-point depression constant; m = molality. © 2012 by W. W. Norton & Company Sample Exercise 11.9 What is the boiling point of seawater if the concentration of ions in seawater is 1.15 m? © 2012 by W. W. Norton & Company 3 5/25/2012 Sample Exercise 11.10 What is the freezing point of radiator fluid prepared by mixing 1.00 L of ethylene glycol (HOCH2CH2OH, density 1.114 g/mL) with 1.00 L of water (density 1.000 g/mL)? The freezing-point-depression constant of water, Kf, is 1.86°C/m. -

Hydrophobic Forces Between Protein Molecules in Aqueous Solutions of Concentrated Electrolyte

LBNL-47348 Pre print !ERNEST ORLANDO LAWRENCE BERKELEY NATIONAL LABORATORY Hydrophobic Forces Between Protein Molecules in Aqueous Solutions of Concentrated Electrolyte R.A. Curtis, C. Steinbrecher, M. Heinemann, H.W. Blanch, and J .M. Prausnitz Chemical Sciences Division January 2001 Submitted to Biophysical]ournal - r \ ' ,,- ' -· ' .. ' ~. ' . .. "... i ' - (_ '·~ -,.__,_ .J :.r? r Clz r I ~ --.1 w ~ CD DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. LBNL-47348 Hydrophobic Forces Between Protein Molecules in Aqueous Solutions of Concentrated Electrolyte R. A. Curtis, C. Steinbrecher. M. Heinemann, H. W. Blanch and J. M. Prausnitz Department of Chemical Engineering University of California and Chemical Sciences Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory University of California Berkeley, CA 94720, U.S.A. -

The New Formula That Replaces Van't Hoff Osmotic Pressure Equation

New Osmosis Law and Theory: the New Formula that Replaces van’t Hoff Osmotic Pressure Equation Hung-Chung Huang, Rongqing Xie* Department of Neurosciences, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX *Chemistry Department, Zhengzhou Normal College, University of Zhengzhou City in Henan Province Cheng Beiqu excellence Street, Zip code: 450044 E-mail: [email protected] (for English communication) or [email protected] (for Chinese communication) Preamble van't Hoff, a world-renowned scientist, studied and worked on the osmotic pressure and chemical dynamics research to win the first Nobel Prize in Chemistry. For more than a century, his osmotic pressure formula has been written in the physical chemistry textbooks around the world and has been generally considered to be "impeccable" classical theory. But after years of research authors found that van’t Hoff osmotic pressure formula cannot correctly and perfectly explain the osmosis process. Because of this, the authors abstract a new concept for the osmotic force and osmotic law, and theoretically derived an equation of a curve to describe the osmotic pressure formula. The data curve from this formula is consistent with and matches the empirical figure plotted linearly based on large amounts of experimental values. This new formula (equation for a curved relationship) can overcome the drawback and incompleteness of the traditional osmotic pressure formula that can only describe a straight-line relationship. 1 Abstract This article derived a new abstract concept from the osmotic process and concluded it via "osmotic force" with a new law -- "osmotic law". The "osmotic law" describes that, in an osmotic system, osmolyte moves osmotically from the side with higher "osmotic force" to the side with lower "osmotic force". -

Δtb = M × Kb, Δtf = M × Kf

8.1HW Colligative Properties.doc Colligative Properties of Solvents Use the Equations given in your notes to solve the Colligative Property Questions. ΔTb = m × Kb, ΔTf = m × Kf Freezing Boiling K K Solvent Formula Point f b Point (°C) (°C/m) (°C/m) (°C) Water H2O 0.000 100.000 1.858 0.521 Acetic acid HC2H3O2 16.60 118.5 3.59 3.08 Benzene C6H6 5.455 80.2 5.065 2.61 Camphor C10H16O 179.5 ... 40 ... Carbon disulfide CS2 ... 46.3 ... 2.40 Cyclohexane C6H12 6.55 80.74 20.0 2.79 Ethanol C2H5OH ... 78.3 ... 1.07 1. Which solvent’s freezing point is depressed the most by the addition of a solute? This is determined by the Freezing Point Depression constant, Kf. The substance with the highest value for Kf will be affected the most. This would be Camphor with a constant of 40. 2. Which solvent’s freezing point is depressed the least by the addition of a solute? By the same logic as above, the substance with the lowest value for Kf will be affected the least. This is water. Certainly the case could be made that Carbon disulfide and Ethanol are affected the least as they do not have a constant. 3. Which solvent’s boiling point is elevated the least by the addition of a solute? Water 4. Which solvent’s boiling point is elevated the most by the addition of a solute? Acetic Acid 5. How does Kf relate to Kb? Kf > Kb (fill in the blank) The freezing point constant is always greater. -

Osmosis and Osmoregulation Robert Alpern, M.D

Osmosis and Osmoregulation Robert Alpern, M.D. Southwestern Medical School Water Transport Across Semipermeable Membranes • In a dilute solution, ∆ Τ∆ Jv = Lp ( P - R CS ) • Jv - volume or water flux • Lp - hydraulic conductivity or permeability • ∆P - hydrostatic pressure gradient • R - gas constant • T - absolute temperature (Kelvin) • ∆Cs - solute concentration gradient Osmotic Pressure • If Jv = 0, then ∆ ∆ P = RT Cs van’t Hoff equation ∆Π ∆ = RT Cs Osmotic pressure • ∆Π is not a pressure, but is an expression of a difference in water concentration across a membrane. Osmolality ∆Π Σ ∆ • = RT Cs • Osmolarity - solute particles/liter of water • Osmolality - solute particles/kg of water Σ Osmolality = asCs • Colligative property Pathways for Water Movement • Solubility-diffusion across lipid bilayers • Water pores or channels Concept of Effective Osmoles • Effective osmoles pull water. • Ineffective osmoles are membrane permeant, and do not pull water • Reflection coefficient (σ) - an index of the effectiveness of a solute in generating an osmotic driving force. ∆Π Σ σ ∆ = RT s Cs • Tonicity - the concentration of effective solutes; the ability of a solution to pull water across a biologic membrane. • Example: Ethanol can accumulate in body fluids at sufficiently high concentrations to increase osmolality by 1/3, but it does not cause water movement. Components of Extracellular Fluid Osmolality • The composition of the extracellular fluid is assessed by measuring plasma or serum composition. • Plasma osmolality ~ 290 mOsm/l Na salts 2 x 140 mOsm/l Glucose 5 mOsm/l Urea 5 mOsm/l • Therefore, clinically, physicians frequently refer to the plasma (or serum) Na concentration as an index of extracellular fluid osmolality and tonicity. -

Ideal Gas Law PV = Nrt R = Universal Gas Constant R = 0.08206 L-Atm R = 8.314 J Mol-K Mol-K Example

Ideal gas law PV = nRT R = universal gas constant R = 0.08206 L-atm R = 8.314 J mol-K mol-K Example: In the reaction of oxygen with carbon to produce carbon dioxide, how many liters of oxygen at 747 mm Hg and 21.0 °C are needed to react with 24.022 g of carbon? CHEM 102 Winter 2011 Practice: In the reaction of oxygen and hydrogen to make water, how many liters of hydrogen at exactly 0 °C and 1 atm are needed to react with 10.0 g of oxygen? 2 CHEM 102 Winter 2011 Combined gas law V decreases with pressure (V α 1/P). V increases with temperature (V α T). V increases with particles (V α n). Combining these ideas: V α n x T P For a given amount of gas (constant number of particles, ninitial = nafter) that changes in volume, temperature, or pressure: Vinitial α ninitial x Tinitial Pinitial Vafter α nafter x Tafter Pafter ninitial = n after Vinitial x Pinitial = Vafter x Pafter Tinitial Tafter 3 CHEM 102 Winter 2011 Example: A sample of gas is pressurized to 1.80 atm and volume of 90.0 cm3. What volume would the gas have if it were pressurized to 4.00 atm without a change in temperature? 4 CHEM 102 Winter 2011 Example: A 2547-mL sample of gas is at 421 °C. What is the new gas temperature if the gas is cooled at constant pressure until it has a volume of 1616 mL? 5 CHEM 102 Winter 2011 Practice: A balloon is filled with helium.