Program Notes by Laura Artesani, Dma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 1 year for only $29.99* *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. Subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com, or send a check or money order to: Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480 Be sure to include your name, mailing address, and email address! If you have any questions about subscribing, you can contact us at [email protected] or visit us online! Cover Photography © Garry Rollins Issue 67 Fall 2019 Welcome to Galaxy’s Edge: 64 A Travellers Guide to Batuu Contents Disney News ............................................................................ 8 Calendar of Events ...........................................................17 The Spooky Side MOUSE VIEWS .........................................................19 74 Guide to the Magic of Walt Disney World by Tim Foster...........................................................................20 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................24 Shutters and Lenses by Mike Billick .........................................................................26 Travel Tips Grrrr! 82 by Michael Renfrow ............................................................36 Hangin’ With the Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................38 Bears of Disney Disney Cuisine by Erik Johnson ....................................................................40 -

MODEST MUSSORGSKY Born March 21, 1839 in Karevo, Pskov District, Russia; Died March 28, 1881 in St

MODEST MUSSORGSKY Born March 21, 1839 in Karevo, Pskov District, Russia; died March 28, 1881 in St. Petersburg A Night on Bald Mountain (1867; arranged in 1886) Arranged by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) PREMIERE OF WORK: St. Petersburg, October 15, 1886 Russian Symphony Orchestra Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 12 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: woodwinds in pairs plus piccolo, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp and strings In the 1860s, Russian music was just beginning to find its distinctive voice. A number of composers — Balakirev, Cui, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky — explored native musical and folkloric sources as the basis of a national art, and became loosely confederated into a group known as “The Mighty Handful” in Russia and “The Five” in the West. Since their works took their inspiration largely from indigenous legends and folk music, Mussorgsky considered himself lucky to receive a commission in 1861 (when he was just 21) for a dramatic musical composition based on a specifically Russian subject. On January 7th, he wrote to his mentor, Balakirev, “I have received an extremely interesting commission [for music for a drama titled The Witch by his friend Baron Georgy Fyodorovitch Mengden], which I must prepare for next summer. It is this: a whole act to take place on Bald Mountain … a Witches’ Sabbath, separate episodes of sorcerers, a solemn march for all this nastiness, a finale — the glorification of the Sabbath into which is introduced the commander of the whole festival on the Bald Mountain. The libretto is very good. I already have some material for it; it may turn out to be a very good thing.” The mountain to which Mussorgsky referred, well known in Russian legend, is Mount Triglav, near Kiev, reputed to be the site of the annual witches’ sabbath that occurs on St. -

Images Et Citations Littéraires Dans La Musique À Programme De Liszt : Pour Un « Renouvellement De La Musique Par Son Alliance Plus Intime Avec La Poésie »

Les colloques de l’Opéra Comique La modernité française au temps de Berlioz. Février 2010 sous la direction d’Alexandre DRATWICKI et Agnès TERRIER Images et citations littéraires dans la musique à programme de Liszt : pour un « renouvellement de la Musique par son alliance plus intime avec la Poésie » Nicolas DUFETEL Weimar, 1860. Après avoir animé pendant seize ans la vie musicale de cette ville provinciale à l’histoire culturelle extraordinaire, capitale d’un petit grand-duché que son prince, Carl Alexander, ambitionnait de transformer en Florence de l’Allemagne1, Franz Liszt porte un regard rétrospectif sur sa carrière de maître de chapelle « en service extraordinaire » – car c’est bien le titre qu’il a toujours conservé, même après que son prédécesseur, Hippolyte Chélard, n’eut été forcé à prendre sa retraite en 1851. Liszt ne fut donc jamais le « maître de chapelle » tout court de Weimar. Ce détail, loin d’être insignifiant, éclaire de façon importante le statut institutionnel et la liberté de celui qu’on présente habituellement comme le maître de chapelle en titre de Carl Alexander2. En 1 Voir le compte rendu de la conversation entre Carl Alexander et Liszt du 11 février 1861 (D- WRI Grossherzogliches Hausarchiv AXXVI/560a, 156). Cet article est fondé sur des recherches menées à l’Institut für Musikwissenschaft Weimar-Jena dans le cadre d’un programme postdoctoral de la Fondation Alexander von Humbolt (2010-2012). 2 Voir Staats-Handbuch für das Großherzogthum Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach 1855, Weimar, Druck des Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1855, p. 47. Sur ce sujet, voir Nicolas DUFETEL « “Comment continuer et compléter l’œuvre de Charles Auguste et de Goethe, afin d’assurer à Weimar en Allemagne la place qu’occupe Florence en Italie ?” : La politique culturelle de Liszt et Carl Alexander à Weimar (1848-1861) », Les grands centres musicaux dans l’espace germanophone (XVII-XIXe siècle), sous la direction de Jean-François CANDONI et Laure GAUTHIER, Paris : Presses Universitaires de Paris Sorbonne, p. -

Fantasias Music History Through Animation Background

Disney’s Two Fantasias Music History Through Animation Background “The beauty and inspiration of music must not be restricted to a privileged few, but must be made available to every man, woman and child.” - Leopold Stokowski, 1940 “Fantasia is.. the beginning of a new technique for the screen.. and a greater development of sound recording and reproduction.” - Walt Disney, 1940 - Disney’s idea of marrying animation and music had begun in 1929 with the Silly Symphonies series (The Skeleton Dance, 1929, Flowers and Trees, 1932, first Technicolor release, The Old Mill, 1937, first multi-plane animation). Mickey was purposely left out. - by late-1930’s, Mickey’s popularity was failing, so Disney conceived the idea of starring Mickey in a Silly Symphony based on Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice - Disney ran into Stokowski in a Beverly Hills restaurant and discussed the idea with him. They soon elaborated it into a feature length film consisting of several contrasting musical works. Disney at first called it The Concert Feature. - Stokowski suggested Fantasia, a musical term meaning “a composition unrestricted by formal design, free reign for fantasy and imagination” - originally conceived as a continually changing concert program, with new pieces added and old ones withdrawn on a continuing basis. Leopold Stokowski • born in London, 1882 emigrated to New York in 1905 • 1912 conductor of Philadelphia Orchestra • an early champion of recorded orchestra music - • “The recording process will one day reproduce music better than heard in the concert hall” • experiments with 3-channel stereo sound at Bell Labs • Philadelphia Orchestra transmitted over three phone lines to Washington, DC • unconventional positioning of instruments in order to produce a better recording • conducted without a baton (hands only), as shown in Fantasia and parodied in Long Haired Hare • by 1937 was well known to American audiences through film & radio appearances • had developed a 9 microphone recording system (mixed to mono) for earlier film recording. -

TCNJ Orchestra Repertoire • Bach

TCNJ Orchestra Repertoire • Bach - Brandenburg No. 1 • Bach - Brandenburg No. 3 for Strings • Bach: Brandenburg Concerto No.5 • Barber: 1st Essay for Orchestra • Bartók - Magyar Képek (Hungarian Pictures) • Bartók - Roumanian Dances • Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 • Beethoven: Symphony No.6 (Pastorale) • Beethoven - Coriolanus • Beethoven - Egmont • Beethoven - Fidelio • Beethoven - Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor • Beethoven - The Ruins of Athens • Beethoven: Choral Fantasie • Beethoven: Leonora No.3 • Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D • Bernstein - Candide • Bernstein - Symphonic Dances from West Side Story • Bizet - Carmen Suites 1 & 2 • Bizet - Jeux d'Enfants • Britten - Soirées Musicales Op. 9 • Bruch Violin Concerto No.1 in E minor Op.26 • Castelnuovo Tedesco - Concerto in D (Guitar) • Chabrier - Espana • Chabrier: Habanera • Chaminade - Concertino for Flute and Orchestra • Copland - Billy the Kid • Copland - Rodeo • Creston - Accordion Concerto • De Falla - Scenes and Dances from the "Three Cornered Hat" • Debussy - Petite Suite • Debussy - Prélude á l'après midi d'un Faune • Delius - The Walk to the Paradise Garden • Dvořák - Symphony No. 8 in G • Dvořák – Piano Quintet, Op. 81 • Dvořák: Symphony No.9 (From the New World) • Elgar: Cello Concerto in E minor • Elgar-Nimrod from 'The Enigma Variations' • Fauré - Bergamaster Suite • Fauré - Prelude from Pelleas and Melisande • Gershwin - Rhapsody in Blue • Gershwin: Cuban Overture • Ginestera - Danza del Trigo from "Estancia" • Glazunov-Violin Concerto in A Minor • Glinka - Russlan and Ludmilla • Gounod - Faust - Ballet Music • Grieg - Notturno from 'Lyric Suite' Op. 54 No. 3 • Grieg - Piano Concerto in A Minor Op 6 • Grieg - Triumphal March from "Sigurd Jorsalfar" • Haas- Sieben Klangräume • Haydn - Symphony No. 49 in F minor • Humperdink-Hansel and Gretel (Prelude) • Ives - The Unanswered question • Ives: Central Park in the Dark • Khachaturian: "Masquerade" Suite • Kodaly: Hary Janos • Lalo - Scherzo in D minor • Lalo: Le Roi d'Ys • Lecuona - Spanish Dances • Leighton – Festive • Mahler – Symphony No. -

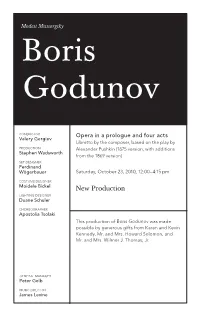

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

CMEA Orchestra Library

CMEA Orchestra Library Title Composer Arranger Publisher Library # Academic Festival Overture Brahms, Johannes Kalmus O-2404A Academic Festival Overture Brahms. Johannes Leidig, Vernon Highland/Etling O-3211B Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 Brahms, Johannes Lucks O-1512B Adagio and Allegro Corelli, Archangelo Lehmeier, Jerry Forest Etling O-3407A Adagio For Strings Barber, Samuel G. Schirmer O-2114 Adagio in Sol Minore (with organ) Albinoni, Tomaso Giazotto, Remo G. Ricordi O-2504B Air For String Orchestra Kalled O-3106C American Rhapsody Niehaus, Lennie Kjos Music Publishers O-3511 American Folk Rhapsody No. 2 Grundman, Clare E. Boosey & Hawkes O-2313 American Salute Gould, Morton Belwin Mills O-2112B American Spiritual Festival Rosenhaus, Steven L. See composer Hal Leonard O-3203C An American Elegy Ticheli, Frank Manhattan Beach O-3409 An English Suite Purcell, Henry Scarmolin Ludwig O-2203A And The Trumpets Sound Turner, Bob Magnolia Music O-0022E Anvil Chorus (from Il Trovatore) Verdi, Giuseppe Dabczynski, Andrew Highland/Etling O-0014E Appalachian Folk Dance Smith, Robert W. Birch Island Music O-0013E Appalachian Hymn Newbold, Soon Hee FJH O-0005E Appalachian Spring Copland O-3518 Arkansas Traveler Muller, Frederick Ludwig Music O-2409B Ashokan Farewell Ungar, Jay Cerulli, Bob Alfred O-3515 Ave Maria Schubert, Franz Moses, Theo. Carl Fischer O-2205A Ave Verum Corpus Mozart, W. A. Woodhouse, Charles Boosey & Hawkes O-2309B Azimuth O'Loughlin, Sean Carl Fischer O-0020E Baba Yaga, op. 56 Liadow, A. Kalmus O-1513 Bacchanale (‘Samson & Delilah’) Saint-Saens, Camille Isaac, Merle Belwin Mills/Kendor O-2503C Ballet Parisien Offenbach, Jacques Issac, Merle Carl Fischer O-2108 Ballet Parisien Offenbach, Jacques Issac Carl Fischer O-3407B Ballet Suite Rameau, J. -

Marching Band Series Listing

14 MARCHING BAND SERIES LISTING ______03744533 Don’t You Worry ’Bout a Thing (Bocook) ....$50.00 LIMITED EDITION _____03744644 l Cumbanchero Brown) ............................ 50.00 _ E ( $ D N GRADES 4-5/SERIES CODE LES ______03744662 Eleanor Rigby (Bocook)...............................$50.00 A ______03744160 After the Love Has Gone/Fantasy ______02500818 Facade (Bocook/Rapp) ................................$60.00 B (Bocook)..................................................$65.00 ______03744923 Fantasmic! – Part 1 (Mickey the Sorcerer) G (Brown) ...................................................$60.00 N ______03744072 Attitude Dance (Bocook)..............................$60.00 I ______03744925 Fantasmic! – Part 2 (Princess Medley) H ______03744325 Birdland (Bocook)........................................$60.00 C ______03744921 Coronation Scene (from Boris Godunov) (Brown) ...................................................$60.00 R (Rapp) .....................................................$80.00 ______03744927 Fantasmic! – Part 3 (Finale) (Brown).........$60.00 A ______11506040 Field Competition Warm-ups (Bocook).......$40.00 M ______10706030 Firebird (Bocook).........................................$40.00 ______10807010 Georgia on My Mind (Higgins) ....................$45.00 ______03744215 Five Olympic Fanfares (Lavender) ..............$50.00 ______03744162 In the Stone (Bocook)..................................$65.00 ______03744625 Firebird Suite (from Fantasia 2000) ______10723073 Luck Be a Lady (Bocook).............................$50.00 -

Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion

Requirements for Audition 1 Requirements for Audition Sub-Principal Percussion March 2019 The NZSO tunes at A440. Auditions must be unaccompanied. Solo 01 | BACH | LUTE SUITE IN E MINOR MVT. 6 – COMPLETE (NO REPEATS) 02 | DELÉCLUSE | ETUDE NO. 9 FROM DOUZE ETUDES - COMPLETE Excerpts BASS DRUM 7 03 | BRITTEN | YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO THE ORCHESTRA .................................. 7 04 | MAHLER | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 1 ......................................................................... 8 05 | PROKOFIEV | SYMPHONY NO. 3 MVT. 4 .................................................................... 9 06 | SHOSTAKOVICH | SYMPHONY NO. 11 MVT. 1 .........................................................10 07 | STRAVINSKY | RITE OF SPRING ...............................................................................10 08 | TCHAIKOVSKY | SYMPHONY NO. 4 MVT. 4 ..............................................................12 BASS DRUM WITH CYMBAL ATTACHMENT 13 09 | STRAVINSKY | PETRUSHKA (1947) ...........................................................................13 New Zealand Symphony Orchestra | Sub-Principal Percussion | March 2019 2 Requirements for Audition CYMBALS 14 10 | DVOŘÁK | SCHERZO CAPRICCIOSO ........................................................................14 11 | MUSSORGSKY | NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN .........................................................14 12 | RACHMANINOV | PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2 MVT. 3 ................................................15 13 | SIBELIUS | FINLANDIA ................................................................................................15 -

Marching Band

81913 MBalpha 5-15 9/20/06 11:15 AM Page 5 MARCHING BAND ALPHABETICAL LISTING......................................................................................6 SERIES LISTING ....................................................................................................16 Series Code Series Name Grade Level(s)* Page No. BMP/MB Band Music Press Marching Band 3-4 24 CM/MB Curnow Music Marching Band 4 25 CMPS/FGHT Campus Fight Songs 3 21 CNT/MB Contemporary Marching Band 3-4 17 COMP Competition Marching Band 3-4 18 CP Crowd Pleasers 2-3 20 DURAND Durand 4 25 ES Esprit 2-3 18 EZCNT Easy Contemporary Marching Band 2-3 19 GSMB G. Schirmer Marching Band 5 25 HL/EZ/MB Hal Leonard Easy Marching Band 2-3 19 HLMB Hal Leonard Marching Band 3-4 17 HL/PC Hal Leonard Power Charts 3 21 INST Marching Band Instructional Materials n/a 25 LES Limited Edition Series 4-5 16 MBCD Marching Band Rehearsal Tracks (CD) n/a 20 MB FOLIOS Marching Band Folios 2-3 22 PELE Performance/Easy Limited Edition 3-4 16 PS Percussion Series 3-4 18 SO Series One 2 21 SP Soundpower 4 16 *Grade Levels 1 = Very Easy (1 year playing experience) 2 = Easy (2 years playing experience) 3 = Medium (3-4 years playing experience) 4 = Medium Advanced 5 = Advanced 81913 MBalpha 5-15 9/20/06 11:15 AM Page 6 6 MARCHING BAND ALPHABETICAL LISTING ______ 03744339 Big Band Opener (Murtha) ES ...............$40.00 A ______ 03744617 Big Time Operator ______ 03744710 ABC (Sweeney) EZCNT.........$40.00 (Saucedo) CNT/MB ......$45.00 ______ 03744784 A Mis Abuelos (Brown) PELE ...........$50.00 -

Franz Liszt: the Ons Ata in B Minor As Spiritual Autobiography Jonathan David Keener James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2011 Franz Liszt: The onS ata in B Minor as spiritual autobiography Jonathan David Keener James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Music Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Keener, Jonathan David, "Franz Liszt: The onS ata in B Minor as spiritual autobiography" (2011). Dissertations. 168. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/168 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Franz Liszt: The Sonata in B Minor as Spiritual Autobiography Jonathan David Keener A document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2011 Table of Contents List of Examples………………………………………………………………………………………….………iii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….v Introduction and Background….……………………………………………………………………………1 Form Considerations and Thematic Transformation in the Sonata…..……………………..6 Schumann’s Fantasie and Alkan’s Grande Sonate…………………………………………………14 The Legend of Faust……………………………………………………………………………………...……21 Liszt and the Church…………………………………………………………………………..………………28