Evolving Fantasia: Listening for Fun and Education in Walt Disney's Dynamic Commodity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

Time 1925 1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Giulio Gatti Casazza 1926 Director, Metropolitan Opera Arturo Toscanini Leopold Stokowski 1926 1930 Conductor Conductor Pietro Mascagni Lucrezia Bori James Cæsar Petrillo 1926 1930 1948 Composer Singer Head, American Federation of Musicians Richard Strauss Alfred Hertz Sergei Koussevitsky Helen Traubel Charles Munch 1938 1927 1930 1946 1949 Composer and conductor Conductor Conductor Singer Conductor Ignace J Paderewski Geraldine Farrar Joseph Deems Taylor Marian Anderson Cole Porter 1939 1927 1931 1946 1949 Kirsten Flagstad Pianist, politician Singer Composer, critic Singer Composer 1935 Lauritz Melchior Giulio Gatti-Casazza Ignace Jan Paderewski Yehudi Menuhin Singer Artur Rodziński Gian Carlo Menotti Maria Callas 1940 1923 1928 1932 1947 1950 1956 Artur Rubinstein Edward Johnson Singer Director, Metropolitan Opera Pianist, politician Violinist; 16 years old Conductor Composer Singer 1966 1936 Leopold Stokowski Pianist Johann Sebastian Bach Nellie Melba Mary Garden Lawrence Tibbett Singer Arturo Toscanini Mario Lanza & Enrico Caruso Leonard Bernstein 1940 1968 1927 1930 1933 1948 1951 1957 Jean Sibelius Conductor Dmitri Shostakovich Composer (1685–1750) Singer Singer Singer Conductor Singers Composer, conductor 1937 1942 Beverly Sills Richard Strauss Rosa Ponselle Arturo Toscanini Composer Composer Benjamin Britten Patrice Munsel Renata Tebaldi Rudolf Bing Luciano Pavarotti 1971 1927 1931 1934 1948 1951 1958 1966 1979 Sergei Koussevitsky Sir Thomas Beecham Leontyne Price Singer Georg Solti Composer, conductor Singer Conductor Composer -

What Is Conductorcise® ?

WHAT IS CONDUCTORCISE® ? Place yourself in the sneakers of an orchestra conductor and raise your baton to a mighty Sousa march, an impetuous Strauss polka, or an elegant Tchaikovsky waltz as you enjoy a great musical workout. CONDUCTORCISE® is a combination aerobic workout, symphonic performance, and music history lesson that swings to the sounds of the masters. A unique program recognized internationally by health and fitness experts, CONDUCTORCISE® fosters upper body fitness that can help strengthen your heart and open your ears and mind in a natural, invigorating workout. This low-impact fitness fusion for all ages stimulates the cardio-vascular system, energizes and engages the senses and creates balance, stretching, blood circulation and brain stimulation throughout the workout. Learn basic conducting techniques, improve cognitive and listening skills, and discover the lives and work of great composers, as you keep your body and mind in tune, relieve stress and secure balance, increase circulation, manage diabetes, and build upper body strength. The brain child of clarinetist/Conductor David Dworkin, it’s an exhilarating and unique alternative to “traditional” exercise programs that has successfully traveled the globe. The only program of its kind in the world, Dworkin has brought it to pre-school children, teenagers, healthy seniors, and those in assisted- living facilities, as well as stroke, wheelchair bound, and Alzheimer’s patients and beyond, allowing participants to keep ones “body and mind in tune.” Who Leads CONDUCTORCISE®: Maestro David Dworkin Maestro David Dworkin has led orchestras across America and abroad, and served as conductor and Artistic Consultant of three PBS Television documentaries in the series Grow Old With Me, including “The Poetry of Aging,” featuring Richard Kiley, Julie Harris, and James Earl Jones. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Season 20 Season 2011-2012

Season 2020111111----2020202011112222 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, March 888,8, at 8:00 Friday, March 999,9, at 222:002:00:00:00 Saturday, March 101010,10 , at 8:00 James Gaffigan Conductor Stewart Goodyear Piano Bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront Gershwin/orch. Grofé Rhapsody in Blue Intermission Tchaikovsky Excerpts from Swan Lake, Op. 20 I. Scene II. Waltz III. Dance of the Swans IV. Scene V. Hungarian Dance, Czardas VI. Spanish Dance VII. Neapolitan Dance VIII. Mazurka IX. Scene X. Dance of the Little Swans XI. Scene XII. Final Scene This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. American conductor James Gaffigan, who is making his Philadelphia Orchestra debut with these performances, was recently appointed chief conductor of the Lucerne Symphony and principal guest conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic; he assumed both posts in the summer of 2011. This season he debuts with the Atlanta Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic and makes return visits to the Minnesota Orchestra and the Baltimore, Dallas, Milwaukee, National, and Toronto symphonies. Recent and upcoming festival appearances include the Aspen, Blossom, Grant Park, and Grand Teton music festivals, and the Spoleto Festival USA. In Europe he makes debuts with the Czech, Dresden, and London philharmonics. In 2009 Mr. Gaffigan completed his three-year tenure as associate conductor with the San Francisco Symphony. Prior to that appointment he was assistant conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra. He has appeared with such North American orchestras as the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and the Chicago, Detroit, Houston, New World, Seattle, and Saint Louis symphonies. -

Tv Pg 6 3-2.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, March 2, 2009 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening March 2, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Lost Lost 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX American Idol Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Criminal Minds CSI: Miami CSI: Miami Criminal Minds Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC To-Mockingbird To-Mockingbird Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Wild Recon Madman of the Sea Wild Recon Untamed and Uncut Madman Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET National Security Vick Tiny-Toya The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Security Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Smarter Smarter Extreme-Home O Brother, Where Art 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY S. -

Unit 7 Romantic Era Notes.Pdf

The Romantic Era 1820-1900 1 Historical Themes Science Nationalism Art 2 Science Increased role of science in defining how people saw life Charles Darwin-The Origin of the Species Freud 3 Nationalism Rise of European nationalism Napoleonic ideas created patriotic fervor Many revolutions and attempts at revolutions. Many areas of Europe (especially Italy and Central Europe) struggled to free themselves from foreign control 4 Art Art came to be appreciated for its aesthetic worth Program-music that serves an extra-musical purpose Absolute-music for the sake and beauty of the music itself 5 Musical Context Increased interest in nature and the supernatural The natural world was considered a source of mysterious powers. Romantic composers gravitated toward supernatural texts and stories 6 Listening #1 Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique (4th mvmt) Pg 323-325 CD 5/30 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwCuFaq2L3U 7 The Rise of Program Music Music began to be used to tell stories, or to imply meaning beyond the purely musical. Composers found ways to make their musical ideas represent people, things, and dramatic situations as well as emotional states and even philosophical ideas. 8 Art Forms Close relationship Literature among all the art Shakespeare forms Poe Bronte Composers drew Drama inspiration from other Schiller fine arts Hugo Art Goya Constable Delacroix 9 Nationalism and Exoticism Composers used music as a tool for highlighting national identity. Instrumental composers (such as Bedrich Smetana) made reference to folk music and national images Operatic composers (such as Giuseppe Verdi) set stories with strong patriotic undercurrents. Composers took an interest in the music of various ethnic groups and incorporated it into their own music. -

The Bbc and the 'Radio Cartoon'

Jackson, V. (2019). ‘What do we get from a Disney film if we cannot see it?’: The BBC and the “Radio Cartoon” 1934-1941. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 39(2), 290-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2018.1522789 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1080/01439685.2018.1522789 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Taylor & Francis at https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2018.1522789 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television ISSN: 0143-9685 (Print) 1465-3451 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/chjf20 ‘What Do We Get from a Disney Film if We Cannot See It?’: The BBC and the ‘Radio Cartoon’ 1934–1941 Victoria Jackson To cite this article: Victoria Jackson (2019): ‘What Do We Get from a Disney Film if We Cannot See It?’: The BBC and the ‘Radio Cartoon’ 1934–1941, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2018.1522789 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2018.1522789 © 2018 The Author(s). -

Film Essay for "This Is Cinerama"

This Is Cinerama By Kyle Westphal “The pictures you are now going to see have no plot. They have no stars. This is not a stage play, nor is it a feature picture not a travelogue nor a symphonic concert or an opera—but it is a combination of all of them.” So intones Lowell Thomas before introduc- ing America to a ‘major event in the history of entertainment’ in the eponymous “This Is Cinerama.” Let’s be clear: this is a hyperbol- ic film, striving for the awe and majesty of a baseball game, a fireworks show, and the virgin birth all rolled into one, delivered with Cinerama gave audiences the feeling they were riding the roller coaster the insistent hectoring of a hypnotically ef- at Rockaway’s Playland. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. fective multilevel marketing pitch. rama productions for a year or two. Retrofitting existing “This Is Cinerama” possesses more bluster than a politi- theaters with Cinerama equipment was an enormously cian on the stump, but the Cinerama system was a genu- expensive proposition—and the costs didn’t end with in- inely groundbreaking development in the history of motion stallation. With very high fixed labor costs (the Broadway picture exhibition. Developed by inventor Fred Waller from employed no less than seventeen union projectionists), an his earlier Vitarama, a multi-projector system used primari- unusually large portion of a Cinerama theater’s weekly ly for artillery training during World War II, Cinerama gross went back into the venue’s operating costs, leaving sought to scrap most of the uniform projection standards precious little for the producers. -

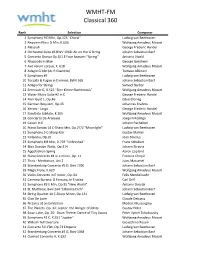

Top 360 Countdown

WMHT-FM Classical 360 Rank Selection Composer 1 Symphony 9 D Min, Op.125 "Choral" Ludwig van Beethoven 2 Requiem Mass D Min, K.626 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 3 Messiah George Frederic Handel 4 Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String Johann Sebastian Bach 5 Concerto Grosso Op.8/1 E Four Seasons "Spring" Antonio Vivaldi 6 Rhapsody in Blue George Gershwin 7 Ave verum corpus, K. 618 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 8 Adagio G Min (Ar R.Giazotto) Tomaso Albinoni 9 Symphony #5 Ludwig van Beethoven 10 Toccata & Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 Johann Sebastian Bach 11 Adagio for Strings Samuel Barber 12 Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 13 Water Music Suite #2 in D George Frederic Handel 14 Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 Edvard Grieg 15 German Requiem, Op.45 Johannes Brahms 16 Xerxes - Largo George Frederic Handel 17 Exsultate Jubilate, K 165 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 18 Concierto De Aranjuez Joaquin Rodrigo 19 Canon in D Johann Pachelbel 20 Piano Sonata 14 C-Sharp Min, Op.27/2 "Moonlight" Ludwig van Beethoven 21 Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min Gustav Mahler 22 Finlandia, Op.26 Jean Sibelius 23 Symphony 8 B Min, D.759 "Unfinished" Franz Schubert 24 Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 Johann Strauss 25 Appalachian Spring Aaron Copland 26 Piano Concerto #1 in e minor, Op. 11 Frederic Chopin 27 Thais - Meditation, Act 2 Jules Massenet 28 Brandenburg Concerto #5 D, Bwv 1050 Johann Sebastian Bach 29 Magic Flute, K.620 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 30 Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.