Homer and the Homeridae, Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Odyssey Passage

The Odyssey of Homer Translated from Greek into English prose in 1879 by S.H. Butcher and Andrew Lang. Book I In a Council of the Gods, Poseidon absent, Pallas procureth an order for the restitution of Odysseus; and appearing to his son Telemachus, in human shape, adviseth him to complain of the Wooers before the Council of the people, and then go to Pylos and Sparta to inquire about his father. Tell me, Muse, of that man, so ready at need, who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy, and many were the men whose towns he saw and whose mind he learnt, yea, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep, striving to win his own life and the return of his company. Nay, but even so he saved not his company, though he desired it sore. For through the blindness of their own hearts they perished, fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios Hyperion: but the god took from them their day of returning. Of these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, whencesoever thou hast heard thereof, declare thou even unto us. Now all the rest, as many as fled from sheer destruction, were at home, and had escaped both war and sea, but Odysseus only, craving for his wife and for his homeward path, the lady nymph Calypso held, that fair goddess, in her hollow caves, longing to have him for her lord. But when now the year had come in the courses of the seasons, wherein the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaca, not even there was he quit of labours, not even among his own; but all the gods had pity on him save Poseidon, who raged continually against godlike Odysseus, till he came to his own country. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

Ulysses Notes Joe Kelly Chapter 1: Telemachus Stephen Dedalus, A

Ulysses Notes Joe Kelly Chapter 1: Telemachus Stephen Dedalus, a young poet employed as a school teacher; Buck Mulligan, a med student; and an Englishman called Haines, who is in Ireland to study Celtic culture, spend their morning in their Martello Tower at the seaside resort town of Sandycove, south of Dublin. Stephen, who is mourning for his dead mother, watches Buck shave on the parapet, they discuss things, Buck goes inside to cook breakfast. They all eat while a local farm woman brings them their milk. Then they walk Martello (now called the "Joyce") Tower at down to the "Forty Foot Hole," where Buck Sandycove swims in Dublin Bay. Pay careful attention to what the swimmers say about the Odyssey, Odysseus was missing, Bannons and the photo girl. presumed dead by most, for ten years after the end of the Trojan War, and Look for parallels between Stephen and his palace and wife in Ithaca were Hamlet, on one hand, and Telemachus, the beset by "suitors" who wanted to son of Odysseus, on the other. In the become king. Ulysses is a sequel to Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which is a bildungsroman starring Stephen Dedalus. That novel ended with Stephen graduating from University College, Dublin and heading off for Paris to launch his literary career. Two years later, he's back in Dublin, having been summoned home by his mother's illness. So he's something of an Icarus figure also, having tried to fly out of the labyrinth of Ireland to freed om, but having fallen, so to speak. -

Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 Pp

Clas 122 2017 Mon Oct 2: Homer and Hesiod: Early Theories of Foreignness (Kennedy, RECW Ch 1 pp. 3-13) Overview of Homer's Odyssey -- a map of the world imagined by speakers of Greek The poem itself invites its audience to think about: What is a good society? What is a good leader? As readers here and now, we can also ask critical Questions: What are the poem's blind spots? How does the poem encourage its audience to think and behave? Do the poem's ideas about a good society and a good leader have meaning today? The images below come from a series of collages and paintings by Romare Bearden (1911-1988). The Smithsonian Institution organized a bautiful exhibit of the series recently, and there is a good free app (showing many of the works and adding audio commentary) available for I phone and android; search for "A Black Odyssey" where you get apps. As our story begins ..... During his journey back to his home in Ithaca after the war at Troy, Odysseus is on the island of Calypso. Athena asks Zeus if Odysseus can come home to Ithaca. Zeus says yes, and sends Hermes to tell Calypso that Odysseus needs to come home. Calypso lets Odysseus build a raft and he departs. This is only possible because .... RECW 1.1 Od. 1.22-26: Poseidon, the god of the sea, is visiting the Ethiopians, and thus is not watching Odysseus. Poseidon had been thwarting the homecoming because of the way that Odysseus treated the Cyclops Polyphemus, who was descended from Poseidon. -

00 Portadillas

La primera Historia de la Literatura romana: el programa de curso de F. A. Wolf (1787) 1 Francisco GarCía -J UradO Bernd MarIzzI Universidad Complutense [email protected] [email protected] recibido: 31 de marzo de 2009 aceptado: 20 de octubre de 2009 RESUMEN Se ofrece por primera vez en versión castellana el programa de Historia de la Literatura romana publi - cado por Friedrich august Wolf en 1787. El programa, escrito originalmente en alemán (y no en latín, como era normal en este tipo de publicaciones), contiene la primera formulación de una historia litera - ria en términos de literatura nacional. asimismo, se hace un estudio biográfico del autor y de su im - pronta en España, al tiempo que se ofrece un comentario de las ideas historiográficas que sustentan el curso, no ajenas a la estética del llamado Clasicismo de Weimar. Palabras clave: Historia literaria. Literatura romana. Friedrich august Wolf. GarCía -J UradO , F., MarIzzI , B., «La primera Historia de la Literatura romana: el programa de curso de F. a. Wolf (1787)», Cuad. fil. clás. Estud. Lat . 29.2 (2009) 145-177. The first History of roman Literature: F. a. Wolf’s lecture programme (1787) AbStRAct This is the first time F. a. Wolf’s History of roman Literature Programme is translated to Spanish since its first edition in 1787. The programme is written in German (not in Latin, as it was usual in this kind of studies), and roman Literature is shown as a national literature. In addition, we study Wolf’s life, his influence in Spain and we offer a commentary on historiographic ideas found in his programme. -

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses Assistant Teacher Haider Ghazi Jassim AL_Jaberi AL.Musawi University of Babylon College of Education Dept. of English Language and Literature [email protected] Abstract Technically accounting, Intertextuality designates the interdependence of a literary text on any literary one in structure, themes, imagery and so forth. As a matter of fact, the term is first coined by Julia Kristeva in 1966 whose contention was that a literary text is not an isolated entity but is made up of a mosaic of quotations, and that any text is the " absorption, and transformation of another"1.She defies traditional notions of the literary influence, saying that Intertextuality denotes a transposition of one or several sign systems into another or others. Transposition is a Freudian term, and Kristeva is pointing not merely to the way texts echo each other but to the way that discourses or sign systems are transposed into one another-so that meanings in one kind of discourses are heaped with meanings from another kind of discourse. It is a kind of "new articulation2". For kriszreve the idea is a part of a wider psychoanalytical theory which questions the stability of the subject, and her views about Intertextuality are very different from those of Roland North and others3. Besides, the term "Intertextuality" describes the reception process whereby in the mind of the reader texts already inculcated interact with the text currently being skimmed. Modern writers such as Canadian satirist W. P. Kinsella in The Grecian Urn4 and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald in Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) have learned how to manipulate this phenomenon by deliberately and continually alluding to previous literary works well known to educated readers, namely John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Shakespeare's tragedies Romeo and Juliet and Othello respectively. -

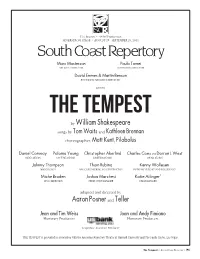

By William Shakespeare Aaron Posner and Teller

51st Season • 483rd Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 28, 2014 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE TEMPEST by William Shakespeare songs by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan choreographer, Matt Kent, Pilobolus Daniel Conway Paloma Young Christopher Akerlind Charles Coes AND Darron L West SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Johnny Thompson Thom Rubino Kenny Wollesen MAGIC DESIGN MAGIC ENGINEERING AND CONSTRUCTION INSTRUMENT DESIGN AND WOLLESONICS Miche Braden Joshua Marchesi Katie Ailinger* MUSIC DIRECTION PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER adapted and directed by Aaron Posner and Teller Jean and Tim Weiss Joan and Andy Fimiano Honorary Producers Honorary Producers Corporate Associate Producer THE TEMPEST is presented in association with the American Repertory Theater at Harvard University and The Smith Center, Las Vegas. The Tempest • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS Prospero, a magician, a father and the true Duke of Milan ............................ Tom Nelis* Miranda, his daughter .......................................................................... Charlotte Graham* Ariel, his spirit servant .................................................................................... Nate Dendy* Caliban, his adopted slave .............................. Zachary Eisenstat*, Manelich Minniefee* Antonio, Prospero’s brother, the usurping Duke of Milan ......................... Louis Butelli* Gonzala, -

The Roles of Solon in Plato's Dialogues

The Roles of Solon in Plato’s Dialogues Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Samuel Ortencio Flores, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Bruce Heiden, Advisor Anthony Kaldellis Richard Fletcher Greg Anderson Copyrighy by Samuel Ortencio Flores 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Plato’s use and adaptation of an earlier model and tradition of wisdom based on the thought and legacy of the sixth-century archon, legislator, and poet Solon. Solon is cited and/or quoted thirty-four times in Plato’s dialogues, and alluded to many more times. My study shows that these references and allusions have deeper meaning when contextualized within the reception of Solon in the classical period. For Plato, Solon is a rhetorically powerful figure in advancing the relatively new practice of philosophy in Athens. While Solon himself did not adequately establish justice in the city, his legacy provided a model upon which Platonic philosophy could improve. Chapter One surveys the passing references to Solon in the dialogues as an introduction to my chapters on the dialogues in which Solon is a very prominent figure, Timaeus- Critias, Republic, and Laws. Chapter Two examines Critias’ use of his ancestor Solon to establish his own philosophic credentials. Chapter Three suggests that Socrates re- appropriates the aims and themes of Solon’s political poetry for Socratic philosophy. Chapter Four suggests that Solon provides a legislative model which Plato reconstructs in the Laws for the philosopher to supplant the role of legislator in Greek thought. -

Sundance Institute Announces Casts for Summer Theatre Laboratory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: June 21, 2006 Irene Cho [email protected], 801.328.3456 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES CASTS FOR SUMMER THEATRE LABORATORY AWARD-WINNING ACTORS ANTHONY RAPP, RAÚL ESPARZA AND OTHERS TO WORKSHOP SEVEN NEW PLAYS AT JULY LAB IN UTAH Salt Lake City, UT – Today, Sundance Institute announced the acting ensemble for the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory, to be held July 10-30, 2006 at the Sundance Resort in Utah. The company includes: Bradford Anderson, Nancy Anderson, Whitney Bashor, Judy Blazer, Reg E. Cathey, Will Chase, Johanna Day, Raúl Esparza, Jordan Gelber, Kimberly Hebert Gregory, Carla Harting, Roderick Hill, Nicholas Hormann, Christina Kirk, Ezra Knight, Judy Kuhn, Anika Larsen, Piter Marek, Kelly McCreary, Chris Messina, Jennifer Mudge, Novella Nelson, Toi Perkins, Anthony Rapp, Gareth Saxe, Tregoney Shepherd, Michael Stuhlbarg and Price Waldman. The seven plays to be developed at the 2006 Sundance Institute Theatre Laboratory include: CITIZEN JOSH, by Josh Kornbluth, directed by David Dower, an improvisational solo show which strives to rescue “democracy” from the sloganeers in a personal autobiographical format; CURRENT NOBODY, by Melissa James Gibson, directed by Daniel Aukin, a modern reinterpretation of Homer’s The Odyssey; GEOMETRY OF FIRE, by Stephen Belber, directed by Lucie Tiberghien, which weaves the story of an American reservist just back from Iraq and a Saudi-American citizen investigating his father’s death; THE EVILDOERS, by David Adjmi, directed by Rebecca Taichman, a play in which the marriage of two couples unravel in a dark yet comedic context; …AND JESUS MOONWALKS THE MISSISSIPPI, by Marcus Gardley, directed by Matt August, a poetic retelling of the Demeter myth set during the Civil War; KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS, book by Robert L. -

Provided by the Internet Classics Archive. See Bottom for Copyright

Provided by The Internet Classics Archive. See bottom for copyright. Available online at http://classics.mit.edu//Homer/iliad.html The Iliad By Homer Translated by Samuel Butler ---------------------------------------------------------------------- BOOK I Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove." On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. -

Homer: an Arabic Portrait1

Edin Muftić Homer: An Arabic portrait1 Homer is rightfully seen as the first teacher of Hellenism, the poet who educated the Greek, who in turn educated Europe. But, as is well known, Europe doesn’t have a monopoly on Greek heritage. It was also present in the Islamic tradition, where it manifested itself differently. Apart from phi- losophy, mathematics, astronomy, medicine and pharmacology, Greek poetry, even if usually not translated, was also widely read among the Arab-Islamic intellectual elite. The author analyses the extent to which Homer’s works circulated, how well known were his poetics, and the influence his verses exerted during the heyday of Classical Arab-Islamic civilization. Keywords: Homer; translation movement; Al-Biruni; arabic poetry; Al-Farabi; Averroes INTRODUCTION The Greek and Arab epic tradition have much in common. Themes of tribal enmity, invasions and plunder, abduction of women, revenge, heroism, chivalry and love feature prom- inently in both traditions. While the Greeks have Hercules, Perseus, Theseus, Odysseus, Jason or Achilles, the Arabs have ʻAntar bin Šaddād (the “Arab Achilles”), Sayf bin ī Yazan, Az-Zīr Sālim and many others. When it comes to the actual performance of poetry, similarities be- Ḏ tween the two traditions are even greater. Homeric aoidos playing his lyre has a direct coun- terpart in Arab rawin playing his rababa. The Arab wandering poet often shares the fate of his Greek colleague (Imruʼ al-Qays, arafa and Al-Aʻšá, and Abū Nuwās and Al-Mutanabbī are the most famous examples). Greek tyrants who were famous for hosting poets like Ibycus, Anacre- Ṭ on, Simonides, Bacchylides or Pindar, while expelling others like Alcaeus, have a royal counter- part in An-Nuʻmān bin al-Mun ir, the ruler of Hira. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars.