Histologic Mimics of Malignant Melanoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Clinical Features of Benign Tumors of the External Auditory Canal According to Pathology

Central Annals of Otolaryngology and Rhinology Research Article *Corresponding author Jae-Jun Song, Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College of Clinical Features of Benign Medicine, 148 Gurodong-ro, Guro-gu, Seoul, 152-703, South Korea, Tel: 82-2-2626-3191; Fax: 82-2-868-0475; Tumors of the External Auditory Email: Submitted: 31 March 2017 Accepted: 20 April 2017 Canal According to Pathology Published: 21 April 2017 ISSN: 2379-948X Jeong-Rok Kim, HwibinIm, Sung Won Chae, and Jae-Jun Song* Copyright Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University College © 2017 Song et al. of Medicine, South Korea OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Background and Objectives: Benign tumors of the external auditory canal (EAC) • External auditory canal are rare among head and neck tumors. The aim of this study was to analyze the clinical • Benign tumor features of patients who underwent surgery for an EAC mass confirmed as a benign • Surgical excision lesion. • Recurrence • Infection Methods: This retrospective study involved 53 patients with external auditory tumors who received surgical treatment at Korea University, Guro Hospital. Medical records and evaluations over a 10-year period were examined for clinical characteristics and pathologic diagnoses. Results: The most common pathologic diagnoses were nevus (40%), osteoma (13%), and cholesteatoma (13%). Among the five pathologic subgroups based on the origin organ of the tumor, the most prevalent pathologic subgroup was the skin lesion (47%), followed by the epithelial lesion (26%), and the bony lesion (13%). No significant differences were found in recurrence rate, recurrence duration, sex, or affected side between pathologic diagnoses. -

CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal

Int. Adv. Otol. 2009; 5:(3) 401-403 CASE REPORT Intradermal Nevus of the External Auditory Canal: A Case Report Sedat Ozturkcan, Ali Ekber, Riza Dundar, Filiz Gulustan, Demet Etit, Huseyin Katilmis Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery ‹zmir Atatürk Research and Training Hospital, Ministry of Health, ‹ZM‹R-TURKEY (SO, AE, FG, DE, HK) Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery Etimesgut Military Hospital , ANKARA-TURKEY (RD) Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in humans; however, its occurrence in the external auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon. The clinical manifestations of pigmented nevus of the EAC have been reported to include ear fullness, foreign body sensation, hearing impairment, and otalgia, but some cases were asymptomatic and were found incidentally. The treatment of choice for a symptomatic intradermal nevus in the EAC is complete excision. There has been no recurrence reported in the literature . A pedunculated, papillomatous hair-bearing lesion was detected in the external auditory canal of the patient who was on follow-up for pruritus. Clinical and pathologic features of an intradermal nevus of the external auditory canal are presented, and the literature reviewed. Submitted : 14 October 2008 Revised : 01 July 2009 Accepted : 09 July 2009 Intradermal nevus is the most common skin tumor in left external auditory canal. Otomicroscopic humans; however, its occurrence in the external examination revealed a pedunculated, papillomatous auditory canal (EAC) is uncommon [1-4]. Intradermal hair-bearing lesion in the postero-inferior cartilaginous nevus is considered to be a form of benign cutaneous portion of the external auditory canal (Figure 1). -

A Histomorphological Analysis

Journal of Pathology of Nepal (2018) Vol. 8, 1384 - 1388 cal Patholo Journal of lini gis f C t o o f N n e io p t a a l i - c 2 o 0 s 1 s 0 PATHOLOGY A N u e d p a n of Nepal l a M m e h d t i a c K al , A ad ss o oc n R www.acpnepal.com iatio bitio n Building Exhi Original Article Benign melanocytic lesions with emphasis on melanocytic nevi – A histomorphological analysis Arnab Ghosh1, Dilasma Ghartimagar1, Sushma Thapa1, Brijesh Sathian2, Binaya Shrestha1, Om Prakash Talwar1 1Department of Pathology, Manipal College of Medical Sciences, Pokhara, Nepal 2Academic research associate, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Melanocytic lesions are common and include both benign and malignant conditions. Compound; Benign melanocytic nevus may show varied microscopic features and should be differentiated from Intradermal; malignant lesions. In the present study, we analyse the histopathological pictures of different types of Melanocytic; benign melanocytic nevi. Nevus; Pigmented; Materials and methods: This study was a hospital based retrospective study and all the cases reported as melanocytic nevus in the period from Jan 2014 to June 2018 in the Department of Pathology, Manipal Teaching Hospital were retrieved and analysed in the study. Results: A total of 104 melanocytic lesions including 74 cases of benign melanocytic nevus were reported in the study period. Females were affected more with a female to male ratio of 1.8:1. The age range was 5 to 78 years with mean age of 28 years. -

Critical Evaluation of the So-Called “Junction Nevus”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE SO-CALLED "JUNCTION NEVUS* S. WILLIAM BECKER, MS., M.D. The serious study of pigmented nevi was undertaken by many workers in the closing years of the 19th Century. All recognized that the microscopic picture of nevi differed from anything seen in other organs. The presence of nevus cells in both the epidermis and dermis led to concepts of origin at one or the other site, or at both sites. Dermal Origin: Demieville (1) believed that the nevus cells arose from adven- titial and endothelial cells of blood vessels. Bauer (2) and vonRecklinghausen (3) thought that the origin was from endothelium of lymph vessels rather than of blood vessels. Epidermal Origin: According to Abesser (4), Duranti, in 1871, was the first to suggest an epidermal origin of nevus cells. Kromayer (5) stated that the endo- thelium-like cells originate in the basal portion of the epidermis as "Bläschen- zellen", migrate to the dermis and develop connective tissue and elastic fibers, a change which he called "desmoplasia". Abesser (4) agreed that the cells origi- ated in the epithelium and lost their intercellular bridges, but migrated into the dermis as epithelium-like cells, and remained such. Unna (6) advanced the concept that the epithelial cells changed by losing their intercellular bridges and multiplied in groups, a process which he called "Ab- sonderung", then migrated as groups to the dermis, which he called "Abtrop- fung", thus forming pigmented nevi. -

Acral Compound Nevus SJ Yun S Korea

University of Pennsylvania, Founded by Ben Franklin in 1740 Disclosures Consultant for Myriad Genetics and for SciBase (might try to sell you a book, as well) Multidimensional Pathway Classification of Melanocytic Tumors WHO 4th Edition, 2018 Epidemiologic, Clinical, Histologic and Genomic Aspects of Melanoma David E. Elder, MB ChB, FRCPA University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Napa, May, 2018 3rd Edition, 2006 Malignant Melanoma • A malignant tumor of melanocytes • Not all melanomas are the same – variation in: – Epidemiology – risk factors, populations – Cell/Site of origin – Precursors – Clinical morphology – Microscopic morphology – Simulants – Genomic abnormalities Incidence of Melanoma D.M. Parkin et al. CSD/Site-Related Classification • Bastian’s CSD/Site-Related Classification (Taxonomy) of Melanoma – “The guiding principles for distinguishing taxa are genetic alterations that arise early during progression; clinical or histologic features of the primary tumor; characteristics of the host, such as age of onset, ethnicity, and skin type; and the role of environmental factors such as UV radiation.” Bastian 2015 Epithelium associated Site High UV Low UV Glabrous Mucosa Benign Acquired Spitz nevus nevus Atypical Dysplastic Spitz Borderline nevus tumor High Desmopl. Low-CSD Spitzoid Acral Mucosal Malignant CSD melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma melanoma 105 Point mutations 103 Structural Rearrangements 2018 WHO Classification of Melanoma • Integrates Epidemiologic, Genomic, Clinical and Histopathologic Features • Assists -

Atypical Mole Syndrome and Dysplastic Nevi: Identification of Populations at Risk for Developing Melanoma - Review Article

CLINICS 2011;66(3):493-499 DOI:10.1590/S1807-59322011000300023 REVIEW Atypical mole syndrome and dysplastic nevi: identification of populations at risk for developing melanoma - review article Juliana Hypo´ lito Silva,I Bianca Costa Soares de Sa´,II Alexandre Leon Ribeiro de A´ vila,II Gilles Landman,III Joa˜ o Pedreira Duprat NetoII I Oncology School Celestino Bourroul - Hospital AC Camargo, Sa˜ o Paulo, SP, Brazil. II Skin Oncology Department - Hospital AC Camargo - Sa˜ o Paulo, SP, Brazil. III Pathology Department - Hospital AC Camargo - Sa˜ o Paulo, SP, Brazil. Atypical Mole Syndrome is the most important phenotypic risk factor for developing cutaneous melanoma, a malignancy that accounts for about 80% of deaths from skin cancer. Because the diagnosis of melanoma at an early stage is of great prognostic relevance, the identification of Atypical Mole Syndrome carriers is essential, as well as the creation of recommended preventative measures that must be taken by these patients. KEYWORDS: Dysplastic Nevus Syndrome; dysplastic nevi; melanoma; early diagnosis; Risk Factors. Silva JH, de Sa´ BC, Avila ALR, Landman G, Duprat Neto JP. Atypical mole syndrome and dysplastic nevi: identification of populations at risk for developing melanoma - review article. Clinics. 2011;66(3):493-499. Received for publication on November 23, 2010; First review completed on November 24, 2010; Accepted for publication on November 24, 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: 55 11 2189-5135 INTRODUCTION Several studies have shown that the presence of dysplas- tic nevi considerably increases the risk of developing The incidence of cutaneous melanoma has increased melanoma, which demonstrates that these lesions, aside rapidly worldwide.1-5 Although it corresponds to only 4% of 4 from being precursors to disease are also important risk all skin cancers, it accounts for 80% of skin cancer deaths. -

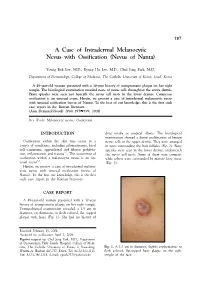

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Characteristic Epiluminescent Microscopic Features of Early Malignant Melanoma on Glabrous Skin a Videomicroscopic Analysis

STUDY Characteristic Epiluminescent Microscopic Features of Early Malignant Melanoma on Glabrous Skin A Videomicroscopic Analysis Shinji Oguchi, MD; Toshiaki Saida, MD, PhD; Yoko Koganehira, MD; Sachiko Ohkubo, MD; Yasushi Ishihara, MD; Shigeo Kawachi, MD, PhD Objective: To investigate the characteristic epilumi- Results: On epiluminescent microscopy, malignant mela- nescent microscopic features of early lesions of malig- noma in situ and the macular portions of invasive malig- nant melanoma affecting glabrous skin, which is the most nant melanoma showed accentuated pigmentation on the prevalent site of the neoplasm in nonwhite populations. ridges of the skin markings, which are arranged in par- allel patterns on glabrous skin. This “parallel ridge pattern” Design: The epiluminescent microscopic features of vari- was found in 5 (83%) of 6 lesions of malignant melanoma ous kinds of melanocytic lesions affecting glabrous skin in situ and in 15 (94%) of 16 lesions of malignant melanoma. were investigated using a videomicroscope. All the di- The parallel ridge pattern was rarely found in the lesions agnoses were determined clinically and histopathologi- of benign melanocytic nevus. Most benign melanocytic nevi cally using the standard criteria. showed 1 of the following 3 typical epiluminescent patterns: (1) a parallel furrow pattern exhibiting pigmentation on the Setting: A dermatology clinic at a university hospital. parallel sulci of the skin markings (54%), (2) a latticelike pattern (21%), and (3) a fibrillar pattern showing filamen- Patients: The following 130 melanocytic lesions con- tous or meshlike pigmentation (15%). The remaining 11 secutively diagnosed at our department were examined: benign nevi (10%) showed a nontypical pattern. 16 lesions of acral lentiginous melanoma, 6 lesions of ma- lignant melanoma in situ, and 108 lesions of benign me- Conclusion: Because epiluminescent microscopic fea- lanocytic nevus (acquired or congenital). -

Application of Teledermoscopy in the Diagnosis of Pigmented Lesions

Hindawi International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications Volume 2018, Article ID 1624073, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1624073 Research Article Application of Teledermoscopy in the Diagnosis of Pigmented Lesions C. B. Barcaui1 andP.M.O.Lima 2 1 Adjunct Professor of Dermatology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, State University of Rio de Janeiro, PhD in Medicine (Dermatology), by University of Sao˜ Paulo, Dermatology Department, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Rio de Janeiro State University, Rio de janeiro, Brazil 2Physician Residing in Dermatology, Department of Dermatology, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Correspondence should be addressed to P. M. O. Lima; [email protected] Received 28 June 2018; Accepted 23 September 2018; Published 10 October 2018 Academic Editor: Aura Ganz Copyright © 2018 C. B. Barcaui and P. M. O. Lima. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Background. Dermatology, due to the peculiar characteristic of visual diagnosis, is suitable for the application of modern telemedicine techniques, such as mobile teledermoscopy. Objectives. To evaluate the feasibility and reliability of the technique for the diagnosis of pigmented lesions. Methods. Trough the storage and routing method, 41 pigmented lesions were analyzed. Afer the selection of the lesions during the outpatient visit, the clinical and dermatoscopic images were obtained by the resident physician through the cellphone camera and sent to the assistant dermatologist by means of an application for exchange of messages between mobile platforms. -

Short Course 11 Pigmented Lesions of the Skin

Rev Esp Patol 1999; Vol. 32, N~ 3: 447-453 © Prous Science, SA. © Sociedad Espafiola de Anatomfa Patol6gica Short Course 11 © Sociedad Espafiola de Citologia Pigmented lesions of the skin Chairperson F Contreras Spain Ca-chairpersons S McNutt USA and P McKee, USA. Problematic melanocytic nevi melanin pigment is often evident. Frequently, however, the lesion is solely intradermal when it may be confused with a fibrohistiocytic RH. McKee and F.R.C. Path tumor, particularly epithelloid cell fibrous histiocytoma (4). It is typi- cally composed of epitheliold nevus cells with abundant eosinophilic Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, cytoplasm and large, round, to oval vesicular nuclei containing pro- USA. minent eosinophilic nucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclu- sions are common and mitotic figures are occasionally present. The nevus cells which are embedded in a dense, sclerotic connective tis- Whether the diagnosis of any particular nevus is problematic or not sue stroma, usually show maturation with depth. Less frequently the nevus is composed solely of spindle cells which may result in confu- depends upon a variety of factors, including the experience and enthusiasm of the pathologist, the nature of the specimen (shave vs. sion with atrophic fibrous histiocytoma. Desmoplastic nevus can be distinguished from epithelloid fibrous histiocytoma by its paucicellu- punch vs. excisional), the quality of the sections (and their staining), larity, absence of even a focal storiform growth pattern and SiQO pro- the hour of the day or day of the week in addition to the problems relating to the ever-increasing range of histological variants that we tein/HMB 45 expression. -

Digital Epiluminescence Microscopy Monitoring of High-Risk Patients

STUDY Digital Epiluminescence Microscopy Monitoring of High-Risk Patients June K. Robinson, MD; Brian J. Nickoloff, MD, PhD Objective: To examine the outcome of digital epilumi- dence in and comfort with dermatologic surveillance and nescence microscopic (DELM) surveillance of atypical skin self-examination performance were assessed. nevi in a high-risk population for 4 years. Results: During annual surveillance with DELM, 5.5% of Design: Atypical, flat melanocytic lesions in 100 pa- the lesions changed. Among the 193 excisional biopsy speci- tients at high risk of developing melanoma were fol- mens there were 4 melanomas in situ, 169 dysplastic nevi, lowed annually with DELM. Pigmentary changes or an and 20 common nevi. Confidence in and comfort with sur- increase in DELM diameter of 1 mm or greater was an veillance and skin self-examination improved after DELM. indication to perform an excisional biopsy. Conclusions: The criteria applied to detect substantial Setting: Cardinal Bernardin Cancer Center Melanoma DELM changes were an increase in DELM diameter of 1 Program, Loyola University Health System, Maywood. mm or greater and pigmentary changes, including ra- dial streaming, focal enlargement, peripheral black dots, Patients: A consecutive sample of 3482 lesions from 100 and “clumping” within the irregular pigment network. patients (aged 18-65 years) with at least 2 images of the Use of DELM enhanced confidence in and comfort with same lesion. care, which extended to performing more extensive skin self-examination. Main Outcome Measures: