2020 Georgia Statewide Air Service Study: Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runway Excursion During Landing, Delta Air Lines Flight 1086, Boeing MD-88, N909DL, New York, New York, March 5, 2015

Runway Excursion During Landing Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 Boeing MD-88, N909DL New York, New York March 5, 2015 Accident Report NTSB/AAR-16/02 National PB2016-104166 Transportation Safety Board NTSB/AAR-16/02 PB2016-104166 Notation 8780 Adopted September 13, 2016 Aircraft Accident Report Runway Excursion During Landing Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 Boeing MD-88, N909DL New York, New York March 5, 2015 National Transportation Safety Board 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2016. Runway Excursion During Landing, Delta Air Lines Flight 1086, Boeing MD-88, N909DL, New York, New York, March 5, 2015. Aircraft Accident Report NTSB/AAR-16/02. Washington, DC. Abstract: This report discusses the March 5, 2015, accident in which Delta Air Lines flight 1086, a Boeing MD-88 airplane, N909DL, was landing on runway 13 at LaGuardia Airport, New York, New York, when it departed the left side of the runway, contacted the airport perimeter fence, and came to rest with the airplane’s nose on an embankment next to Flushing Bay. The 2 pilots, 3 flight attendants, and 98 of the 127 passengers were not injured; the other 29 passengers received minor injuries. The airplane was substantially damaged. Safety issues discussed in the report relate to the use of excessive engine reverse thrust and rudder blanking on MD-80 series airplanes, the subjective nature of braking action reports, the lack of procedures for crew communications during an emergency or a non-normal event without operative communication systems, inaccurate passenger counts provided to emergency responders following an accident, and unclear policies regarding runway friction measurements and runway condition reporting. -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Comprehensive Plan City of Hibbing (St

Comprehensive Plan City of Hibbing (St. Louis County, MN) Accepted and Filed by Vote of Hibbing City Council on December 19, 2018 Hibbing’s Centennial Fountain located near City Hall, 2018 1 Prepared for: City of Hibbing, MN Hibbing, MN City Offices Phone: (218) 262-3486 Mail: City of Hibbing 401 East 21st Street Hibbing, MN 55746 Website: www.hibbing.mn.us 2 Acknowledgements The City of Hibbing, Hibbing City Council and Comprehensive Planning Steering Committee would like to thank our residents and stakeholders for your valuable contributions to the development of this Comprehensive Plan. Your participation in the survey process, Community Visioning Sessions, interviews and discussions have helped us as a community to define a vision, identify our core community values and establish goals and plans for our future. We have valued your ideas and input and will do our best to include and address them as we all work together to carry this plan forward. We would also like to acknowledge the Iron Range Resources & Rehabilitation Board for providing financial contributions and support for this project. Hibbing City Council and Administration Rick Cannata, Mayor Patty Shafer, Councilor Tom Dicklich, City Administrator Jack Lund, Councilor Patrick L. Garrity, City Clerk/Treasurer Tim Harkonen, Councilor Ray Pierce, Jr., Councilor Jennifer Hoffman Saccoman, Councilor Comprehensive Planning Steering Committee Members Georgia Andria Shaun Germolus Kim McLaughlin James Bayliss Marcia Grahek Heather Matvey Celia Cameron Councilor Jennifer Nathan Pederson Hoffman Saccoman Mayor Rick Cannata James Plese Pat Ives Austin Dusek Jackie Prescott Wayne Kangas Justin Fosso Dan Scally Jennifer Lucarelli Pat Furlong Shari Majkich Brock Nicole Gandrud Plan Adoption The Hibbing City Council this Comprehensive Plan during its regularly scheduled public meeting on December 19, 2018. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Essential Air Service (EAS) Communities (Excluding Alaska and Hawaii)* As of February 2020

Eligible Essential Air Service (EAS) communities (excluding Alaska and Hawaii)* as of February 2020 State EAS Community Docket # at www.regulations.gov Alabama Muscle Shoals DOT-OST-2000-7856 Arizona Page DOT-OST-1997-2694 Arizona Prescott DOT-OST-1996-1899 Arizona Show Low DOT-OST-1998-4409 Arkansas El Dorado/Camden DOT-OST-1997-2935 Arkansas Harrison DOT-OST-1997-2935 Arkansas Hot Springs DOT-OST-1997-2935 Arkansas Jonesboro DOT-OST-1997-2935 California Crescent City DOT-OST-1997-2649 California El Centro DOT-OST-2008-0299 California Merced DOT-OST-1998-3521 California Visalia*** DOT-OST-2004-19916 Colorado Alamosa DOT-OST-1997-2960 Colorado Cortez DOT-OST-1998-3508 Colorado Pueblo DOT-OST-1999-6589 Georgia Macon DOT-OST-2007-28671 Illinois Decatur DOT-OST-2006-23929 Illinois Marion/Herrin DOT-OST-2000-7881 Illinois Quincy DOT-OST-2003-14492 Iowa Burlington DOT-OST-2001-8731 Iowa Fort Dodge DOT-OST-2001-10682 Iowa Mason City DOT-OST-2001-10684 Eligible Essential Air Service (EAS) communities (excluding Alaska and Hawaii)* as of February 2020 State EAS Community Docket # at www.regulations.gov Iowa Sioux City** DOT-OST-2011-0131 Iowa Waterloo DOT-OST-2011-0132 Kansas Dodge City DOT-OST-1998-3502 Kansas Garden City DOT-OST-1998-3503 Kansas Hays DOT-OST-1998-3497 Kansas Liberal/Guymon, OK DOT-OST-1998-3498 Kansas Salina DOT-OST-2002-11376 Kentucky Owensboro DOT-OST-2000-7855 Kentucky Paducah DOT-OST-2009-0299 Maine Augusta/Waterville DOT-OST-1997-2784 Maine Bar Harbor DOT-OST-2011-0138 Maine Presque Isle/Houlton DOT-OST-2000-8012 Maine Rockland DOT-OST-1997-2784 Michigan Alpena DOT-OST-2009-0300 Michigan Escanaba DOT-OST-2003-15128 Michigan Hancock/Houghton DOT-OST-2009-0302 Michigan Iron Mountain/Kingsford DOT-OST-1999-5175 Michigan Ironwood/Ashland, WI DOT-OST-1999-1266 Michigan Manistee/Ludington DOT-OST-1996-1711 Michigan Muskegon DOT-OST-2009-0301 Michigan Pellston DOT-OST-2011-0133 Michigan Sault Ste. -

Notice of Adjustments to Service Obligations

Served: May 12, 2020 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR SERVICE PURSUANT TO PUBLIC LAW NO. 116-136 §§ 4005 AND 4114(b) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 NOTICE OF ADJUSTMENTS TO SERVICE OBLIGATIONS Summary By this notice, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) announces an opportunity for incremental adjustments to service obligations under Order 2020-4-2, issued April 7, 2020, in light of ongoing challenges faced by U.S. airlines due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) public health emergency. With this notice as the initial step, the Department will use a systematic process to allow covered carriers1 to reduce the number of points they must serve as a proportion of their total service obligation, subject to certain restrictions explained below.2 Covered carriers must submit prioritized lists of points to which they wish to suspend service no later than 5:00 PM (EDT), May 18, 2020. DOT will adjudicate these requests simultaneously and publish its tentative decisions for public comment before finalizing the point exemptions. As explained further below, every community that was served by a covered carrier prior to March 1, 2020, will continue to receive service from at least one covered carrier. The exemption process in Order 2020-4-2 will continue to be available to air carriers to address other facts and circumstances. Background On March 27, 2020, the President signed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security Act (the CARES Act) into law. Sections 4005 and 4114(b) of the CARES Act authorize the Secretary to require, “to the extent reasonable and practicable,” an air carrier receiving financial assistance under the Act to maintain scheduled air transportation service as the Secretary deems necessary to ensure services to any point served by that air carrier before March 1, 2020. -

The Political Economy of the Essential Air Service Program

Department of Economics Working Paper Series The Political Economy of the Essential Air Service Program Joshua Hall, Amanda Ross and Christopher Yencha Working Paper No. 15-18 This paper can be found at the College of Business and Economics Working Paper Series homepage: http://be.wvu.edu/phd_economics/working-papers.htm The Political Economy of the Essential Air Service Program Joshua Hall* Associate Professor of Economics West Virginia University PO Box 6025 Morgantown, WV 26506 [email protected] Amanda Ross West Virginia University PO Box 6025 Morgantown, WV 26506 [email protected] Christopher Yencha West Virginia University PO Box 6025 Morgantown, WV 26506 [email protected] Abstract We find that congressional influences affect the amount of airport subsidies that a congressional district receives from the Essential Air Service (EAS) program. The EAS program was passed with the goal of helping to continue commercial air service to rural communities following the deregulation of the airline industry. Using subsidy data from 1998-2014, we find strong evidence that subsidies are higher in districts having congressional representation on the House Transportation Committee. Representation on the House Appropriations Committee is also associated with higher subsidies. Our empirical results, combined with news reports, are consistent with the EAS serving private as well as public interests. Keywords: congressional dominance, deregulation, airports JEL Codes: D73, L93 * Corresponding author. The authors would like to acknowledge the helpful comments of E. Frank Stephenson, John Dove, Jamie Bologna, and session participants at the 2015 Public Choice Society meetings in San Antonio, TX. The political economy of the Essential Air Service program 1 Introduction The structure of the airline industry in the United States changed dramatically in 1978 with the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act (ADA). -

Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999

9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 171 Appendix C Informal Complaints to DOT by New Entrant Airlines About Unfair Exclusionary Practices March 1993 to May 1999 UNFAIR PRICING AND CAPACITY RESPONSES 1. Date Raised: May 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Northwest Airlines Description: AccessAir, a new airline headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa, began service in the New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles to Mo- line/Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois, markets. Northwest offers connecting service in these markets. AccessAir alleged that Northwest was offering fares in these markets that were substantially below Northwest’s costs. 171 9310-08 App C 10/12/99 13:40 Page 172 172 ENTRY AND COMPETITION IN THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY 2. Date Raised: March 1999 Complaining Party: AccessAir Complained Against: Delta, Northwest, and TWA Description: AccessAir was a new entrant air carrier, headquartered in Des Moines, Iowa. In February 1999, AccessAir began service to New York–LaGuardia and Los Angeles from Des Moines, Iowa, and Moline/ Quad Cities/Peoria, Illinois. AccessAir offered direct service (nonstop or single-plane) between these points, while competitors generally offered connecting service. In the Des Moines/Moline–Los Angeles market, Ac- cessAir offered an introductory roundtrip fare of $198 during the first month of operation and then planned to raise the fare to $298 after March 5, 1999. AccessAir pointed out that its lowest fare of $298 was substantially below the major airlines’ normal 14- to 21-day advance pur- chase fares of $380 to $480 per roundtrip and was less than half of the major airlines’ normal 7-day advance purchase fare of $680. -

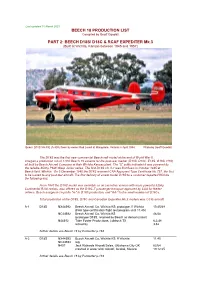

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

Before the Us Department Of

BEFORE THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. ) CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR ) SERVICE ) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 ) Under Public Law 116-336 §§ 4005 and 4114 (b) ) ) REQUEST FOR EXEMPTION FROM SERVICE OBLIGATION Communications with respect to this document should be sent to: Matthew Chaifetz Chief Executive Officer CORPORATE FLIGHT MANAGEMENT INC. 808 Blue Angel Way Smyrna, TN 37167 (516) 946-0482 [email protected] April 18, 2020 3 BEFORE THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. ) CONTINUATION OF CERTAIN AIR ) SERVICE ) Docket DOT-OST-2020-0037 ) Under Public Law 116-336 §§ 4005 and 4114 (b) ) ) REQUEST FOR EXEMPTION FROM SERVICE OBLIGATION Corporate Flight Management, Inc. d/b/a Contour Airlines (“Contour” or the “Company”) is a direct air carrier that holds authority from the Federal Aviation Administration (“FAA”) to conduct passenger flights in common carriage under 14 CFR Part 135 and has been granted Commuter Economic Authority by the DOT under 14 CFR Part 298. Contour provides passenger service in the form of 14 CFR Part 380 public charter flights on a subsidized basis to several small communities participating in the Alternate Essential Air Service Pilot Program (“AEAS”) and has also provided public charter passenger service to other communities on an at- risk basis. The Company has applied to the Treasury Department for passenger air carrier economic assistance under Title IV, Subtitles A and B of Public Law 116-136, commonly referred to as the CARES Act (the “Act”). While Contour has not yet received any funds pursuant to the Act, it reasonably anticipates receiving an initial payment from the Treasury in the near future. -

The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan Promotes a More Efficient

CHAPTER 5 STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS – VERSION 5 CHAPTER 5 STRATEGIC INVESTMENTS INTRODUCTION This chapter sets forth plans of action for the region to pursue and meet identified transportation needs and issues. Planned investments are consistent with the goals and policies of the plan, the Sustainable Community Strategy element (see chapter 4) and must be financially constrained. These projects are listed in the Constrained Program of Projects (Table 5-1) and are modeled in the Air Quality Conformity Analysis. The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan promotes Forecast modeling methods in this Regional Transportation a more efficient transportation Plan primarily use the “market-based approach” based on demographic data and economic trends (see chapter 3). The system that calls for fully forecast modeling was used to analyze the strategic funding alternative investments in the combined action elements found in this transportation modes, while chapter.. emphasizing transportation demand and transporation Alternative scenarios are not addressed in this document; they are, however, addressed and analyzed for their system management feasibility and impacts in the Environmental Impact Report approaches for new highway prepared for the 2014 Regional Transportation Plan, as capacity. required by the California Environmental Quality Act (State CEQA Guidelines Sections 15126(f) and 15126.6(a)). From this point, the alternatives have been predetermined and projects that would deliver the most benefit were selected. The 2014 Regional Transportation Plan promotes a more efficient transportation system that calls for fully funding alternative transportation modes, while emphasizing transportation demand and transporation system management approaches for new highway capacity. The Constrained Program of Projects (Table 5-1) includes projects that move the region toward a financially constrained and balanced system. -

RASG-PA ESC/29 — WP/04 14/11/17 Twenty

RASG‐PA ESC/29 — WP/04 14/11/17 Twenty ‐ Ninth Regional Aviation Safety Group — Pan America Executive Steering Committee Meeting (RASG‐PA ESC/29) ICAO NACC Regional Office, Mexico City, Mexico, 29‐30 November 2017 Agenda Item 3: Items/Briefings of interest to the RASG‐PA ESC PROPOSAL TO AMEND ICAO FLIGHT DATA ANALYSIS PROGRAMME (FDAP) RECOMMENDATION AND STANDARD TO EXPAND AEROPLANES´ WEIGHT THRESHOLD (Presented by Flight Safety Foundation and supported by Airbus, ATR, Embraer, IATA, Brazil ANAC, ICAO SAM Office, and SRVSOP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Flight Data Analysis Program (FDAP) working group comprised by representatives of Airbus, ATR, Embraer, IATA, Brazil ANAC, ICAO SAM Office, and SRVSOP, is in the process of preparing a proposal to expand the number of functional flight data analysis programs. It is anticipated that a greater number of Flight Data Analysis Programs will lead to significantly greater safety levels through analysis of critical event sets and incidents. Action: The FDAP working group is requesting support for greater implementation of FDAP/FDMP throughout the Pan American Regions and consideration of new ICAO standards through the actions outlined in Section 4 of this working paper. Strategic Safety Objectives: References: Annex 6 ‐ Operation of Aircraft, Part 1 sections as mentioned in this working paper RASG‐PA ESC/28 ‐ WP/09 presented at the ICAO SAM Regional Office, 4 to 5 May 2017. 1. Introduction 1.1 Flight Data Recorders have long been used as one of the most important tools for accident investigations such that the term “black box” and its recovery is well known beyond the aviation industry.