The Autonomous District of South Ossetia (ADSO)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map

Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is preparing sector assessments and road maps to help align future ADB support with the needs and strategies of developing member countries and other development partners. The transport sector assessment of Georgia is a working document that helps inform the development of country partnership strategy. It highlights the development issues, needs and strategic assistance priorities of the transport sector in Georgia. The knowledge product serves as a basis for further dialogue on how ADB and the government can work together to tackle the challenges of managing transport sector development in Georgia in the coming years. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.7 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 828 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. Georgia Transport Sector ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main Assessment, Strategy, instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. and Road Map TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS. Georgia. 2014 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed in the Philippines Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

Law of Georgia Tax Code of Georgia

LAW OF GEORGIA TAX CODE OF GEORGIA SECTION I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter I - Georgian Tax System Article 1 - Scope of regulation In accordance with the Constitution of Georgia, this Code sets forth the general principles of formation and operation of the tax system of Georgia, governs the legal relations involved in the movement of passengers, goods and vehicles across the customs border of Georgia, determines the legal status of persons, tax payers and competent authorities involved in legal relations, determines the types of tax offences, the liability for violating the tax legislation of Georgia, the terms and conditions for appealing wrongful acts of competent authorities and of their officials, lays down procedures for settling tax disputes, and governs the legal relations connected with the fulfilment of tax liabilities. Law of Georgia No 5942 of 27 March 2012 - website, 12.4.2012 Article 2 - Tax legislation of Georgia 1. The tax legislation of Georgia comprises the Constitution of Georgia, international treaties and agreements, this Code and subordinate normative acts adopted in compliance with them. 2. The tax legislation of Georgia in effect at the moment when tax liability arises shall be used for taxation. 3. The Government of Georgia or the Minister for Finance of Georgia shall adopt/issue subordinate normative acts for enforcing this Code. 4. (Deleted - No 1886, 26.12.2013) 5. To enforce the tax legislation of Georgia, the head of the Legal Entity under Public Law (LEPL) within the Ministry for Finance of Georgia - the Revenue Service (‘the Revenue Service’) shall issue orders, internal instructions and guidelines on application of the tax legislation of Georgia by tax authorities. -

15 Day Georgian Holidays Cultural & Sightseeing Tours

15 Day Georgian Holidays Cultural & Sightseeing Tours Overview Georgian Holidays - 15 Days/14 Nights Starts from: Tbilisi Available: April - October Type: Private multy-day cultural tour Total driving distance: 2460 km Duration: 15 days Tour takes off in the capital Tbilisi, and travels through every corner of Georgia. Visitors are going to sightsee major cities and towns, provinces in the highlands of the Greater and Lesser Caucasus mountains, the shores of the Black Sea, natural wonders of the West Georgia, traditional wine- making areas in the east, and all major historico-cultural monuments of the country. This is very special itinerary and covers almost all major sights in Tbilisi, Telavi, Mtskheta, Kazbegi, Kutaisi, Zugdidi, Mestia, and Batumi. Tour is accompanied by professional and experienced guide and driver that will make your journey smooth, informational and unforgettable. Preview or download tour description file (PDF) Tour details Code: TB-PT-GH-15 Starts from: Tbilisi Max. Group Size: 15 Adults Duration: 15 Days Prices Group size Price per adult Solo 3074 € 2-3 people 1819 € 4-5 people 1378 € 6-7 people 1184 € 8-9 people 1035 € 10-15 people 1027 € *Online booking deposit: 60 € The above prices (except for solo) are based on two people sharing a twin/double room accommodation. 1 person from the group will be FREE of charge if 10 and more adults are traveling together Child Policy 0-1 years - Free 2-6 years - 514 € *Online booking deposit will be deducted from the total tour price. As 7 years and over - Adult for the remaining sum, you can pay it with one of the following methods: Bank transfer - in Euro/USD/GBP currency, no later than two weeks before the tour starts VISA/Mastercard - in GEL (local currency) in Tbilisi only, before the tour starts, directly to your guide via POS terminal. -

Assemblée Générale Distr

Nations Unies A/HRC/13/21/Add.3 Assemblée générale Distr. générale 14 janvier 2010 Français Original: anglais Conseil des droits de l’homme Treizième session Point 3 de l’ordre du jour Promotion et protection de tous les droits de l’homme, civils, politiques, économiques, sociaux et culturels, y compris le droit au développement Rapport soumis par le Représentant du Secrétaire général pour les droits de l’homme des personnes déplacées dans leur propre pays, Walter Kälin* Additif Suite donnée au rapport sur la mission en Géorgie (A/HRC/10/13/Add.2)** * Soumission tardive. ** Le résumé du présent rapport est distribué dans toutes les langues officielles. Le rapport, qui est joint en annexe au résumé, n’est distribué que dans la langue originale. GE.10-10252 (F) 250110 260110 A/HRC/13/21/Add.3 Résumé Le Représentant du Secrétaire général pour les droits de l’homme des personnes déplacées dans leur propre pays s’est rendu, les 5 et 6 novembre 2009, dans la région de Tskhinvali (Ossétie du Sud) afin de donner suite à la mission qu’il avait effectuée en Géorgie en octobre 2008. Il a pu avoir accès à toutes les zones qu’il avait demandé à voir, y compris à la région de Tskhinvali et aux districts d’Akhalgori et de Znauri, et il a tenu des consultations franches et ouvertes avec les autorités de facto d’Ossétie du Sud. En raison du conflit d’août 2008, 19 381 personnes ont été déplacées au-delà de la frontière de facto, tandis que, selon les estimations, entre 10 000 et 15 000 personnes ont été déplacées à l’intérieur de la région de Tskhinvali (Ossétie du Sud). -

Economic Rehabilitation Works Issue 2 March 2009 a Unique Initiative

Economic Rehabilitation Works Issue 2 March 2009 A unique initiative When launching the Economic Rehabilitation Programme, the Sides* of the conflict settlement process agreed unanimously that projects for the economic rehabilitation of the conflict zone (and adjacent areas) would provide an effective mechanism for confidence-building and, ultimately, for a resolution of the conflict. It was also understood that economic rehabilitation could: • create opportunities for developing regional trade and transit, using the potential of the Trans Caucasian Highway (TRANSCAM) • improve the investment climate • help strengthen peace and security in the whole region. The first milestone in developing the programme came in November 2005, when the OSCE Mission to Georgia launched a major new initiative – a Needs Assessment Study. This yielded a mutually-agreed list of urgent projects for socio-economic infrastructure in the zone of conflict and surrounding areas. The international community responded to this initiative by funding the study, and by pledging – at a specially convened conference in Brussels in June 2006 – some €8 million for implementation of the projects upon which the Sides agreed. Once established, the programme enjoyed some important successes, particularly on the ground with communities. However the deteriorating political and security situation created a very challenging environment, and the outbreak of fighting in August had a severely adverse effect on the programme. After ERP assessment of the circumstances of farmers and SMEs in accessible communities the donors wished to continue with economic rehabilitation in the area. At this stage, access for all involved communities, as originally envisaged for the ERP, was impossible. Therefore as an effective interim solution, the Transitional Economic Rehabilitation Programme (TERP) was launched. -

FÁK Állomáskódok

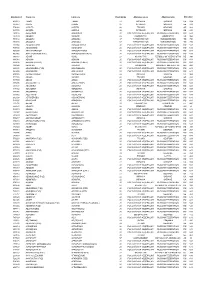

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Doing Business in Georgia: 2015 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in Georgia: 2015 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. • Chapter 1: Doing Business In Georgia • Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment • Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services • Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment • Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards • Chapter 6: Investment Climate • Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing • Chapter 8: Business Travel • Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events • Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Chapter 1: Doing Business in Georgia • Market Overview • Market Challenges • Market Opportunities • Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top Market Overview Georgia is a small transitional market economy of 3.7 million people with a per capita GDP of $3,681 (2014). Georgia is located at the crossroads between Europe and Central Asia and has experienced economic growth over the past twelve years. In June 2014, Georgia signed an Association Agreement (AA) and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the European Union. Through reduced tariffs and the removal of technical barriers to entry, the DCFTA gives Georgian products access to over 500 million people in the EU. Reciprocally, products from the EU now enjoy easier access to the Georgian market. Following the launch of the U.S.-Georgia Strategic Partnership Commission (SPC) in 2009, the U.S. Department of State holds regular meetings with its Georgian counterparts across various working groups. One of these dialogues is the Economic, Energy, and Trade Working Group which aims to coordinate Georgia’s strategy for development in these areas and to explore ways to expand bilateral economic cooperation. -

PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL of KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N O 27 — 2017 2

1 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N o 27 — 2017 2 E DITOR- IN-CHIEF David KOLBAIA S ECRETARY Sophia J V A N I A EDITORIAL C OMMITTEE Jan M A L I C K I, Wojciech M A T E R S K I, Henryk P A P R O C K I I NTERNATIONAL A DVISORY B OARD Zaza A L E K S I D Z E, Professor, National Center of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Alejandro B A R R A L – I G L E S I A S, Professor Emeritus, Cathedral Museum Santiago de Compostela Jan B R A U N (†), Professor Emeritus, University of Warsaw Andrzej F U R I E R, Professor, Universitet of Szczecin Metropolitan A N D R E W (G V A Z A V A) of Gori and Ateni Eparchy Gocha J A P A R I D Z E, Professor, Tbilisi State University Stanis³aw L I S Z E W S K I, Professor, University of Lodz Mariam L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emerita, Tbilisi State University Guram L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emeritus, Tbilisi State University Marek M ¥ D Z I K (†), Professor, Maria Curie-Sk³odowska University, Lublin Tamila M G A L O B L I S H V I L I, Professor, National Centre of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Lech M R Ó Z, Professor, University of Warsaw Bernard OUTTIER, Professor, University of Geneve Andrzej P I S O W I C Z, Professor, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Annegret P L O N T K E - L U E N I N G, Professor, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena Tadeusz Ś W I Ę T O C H O W S K I (†), Professor, Columbia University, New York Sophia V A S H A L O M I D Z E, Professor, Martin-Luther-Univerity, Halle-Wittenberg Andrzej W O Ź N I A K, Professor, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 3 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES No 27 — 2017 (Published since 1991) CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES FACULTY OF ORIENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW WARSAW 2017 4 Cover: St. -

ON the EFFECTIVE USE of PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Andrew Peek All Rights Reserved

ON THE EFFECTIVE USE OF PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 2021 Andrew Peek All rights reserved Abstract This dissertation asks a simple question: how are states most effectively conducting proxy warfare in the modern international system? It answers this question by conducting a comparative study of the sponsorship of proxy forces. It uses process tracing to examine five cases of proxy warfare and predicts that the differentiation in support for each proxy impacts their utility. In particular, it proposes that increasing the principal-agent distance between sponsors and proxies might correlate with strategic effectiveness. That is, the less directly a proxy is supported and controlled by a sponsor, the more effective the proxy becomes. Strategic effectiveness here is conceptualized as consisting of two key parts: a proxy’s operational capability and a sponsor’s plausible deniability. These should be in inverse relation to each other: the greater and more overt a sponsor’s support is to a proxy, the more capable – better armed, better trained – its proxies should be on the battlefield. However, this close support to such proxies should also make the sponsor’s influence less deniable, and thus incur strategic costs against both it and the proxy. These costs primarily consist of external balancing by rival states, the same way such states would balance against conventional aggression. Conversely, the more deniable such support is – the more indirect and less overt – the less balancing occurs. -

2.1.1~2.1.4 95/06/12

Appendices Appendix-1 Member List of the Study Team (1) Field Survey 1. Dr. Yoshiko TSUYUKI Team Leader/ Technical Official, Experts Service Division, Technical Advisor Bureau of International Cooperation International Medical Center of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2. Mr. Hideo EGUCHI Security Control Deputy Resident Representative, Planner United Kingdom Office (JICA) 3. Mr. Yoshimasa TAKEMURA Project Coordinator Staff, Second Management Division, Grant Aid Management Department (JICA) 4. Mr. Yoshiharu HIGUCHI Project Manager CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 5. Dr. Tomoyuki KURODA Health Sector Surveyor CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 6. Mr. Hiroshi MORII Equipment Planner CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 7. Mr. Haruo ITO Equipment Planner / CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. Cost and Procurement Planner 8. Ms. Rusudan PIRVELI Interpreter CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. (2) Explanation of Draft Report 1. Dr. Yoshiko TSUYUKI Team Leader/ Technical Official, Experts Service Division, Technical Advisor Bureau of International Cooperation International Medical Center of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2. Mr. Yoshimasa TAKEMURA Project Coordinator Staff, Second Management Division, Grant Aid Management Department (JICA) 3. Mr. Yoshiharu HIGUCHI Project Manager CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 4. Mr. Hiroshi MORII Equipment Planner CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 5. Ms. Rusudan PIRVELI Interpreter CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. A-1 Appendix-2 Study Schedule (1) Field Survey No. Date Movement Activities Accommodation 1 Apr. 5 (Sat) Narita→Frankfurt Frankfurt (A) (B) (D) (A) (C) (D) 2 Apr. 6 (Sun) Frankfurt→Baku Baku (A) (C) (D) (A) (C) (D) 3 Apr. 7 (Mon) Baku→A) (C) (D) Visit the Embassy of Japan in Baku Train (A) (C) (D) London→(B) (A) (C) (D) Flight (B) (F) (G) Narita→Vienna→ (F) (G) 4 Apr. -

Annexation of Georgia in Russian Empire

1 George Anchabadze HISTORY OF GEORGIA SHORT SKETCH Caucasian House TBILISI 2005 2 George Anchabadze. History of Georgia. Short sketch Above-mentioned work is a research-popular sketch. There are key moments of the history of country since ancient times until the present moment. While working on the sketch the author based on the historical sources of Georgia and the research works of Georgian scientists (including himself). The work is focused on a wide circle of the readers. გიორგი ანჩაბაძე. საქართველოს ისტორია. მოკლე ნარკვევი წინამდებარე ნაშრომი წარმოადგენს საქართველოს ისტორიის სამეცნიერ-პოპულარულ ნარკვევს. მასში მოკლედაა გადმოცემული ქვეყნის ისტორიის ძირითადი მომენტები უძველესი ხანიდან ჩვენს დრომდე. ნარკვევზე მუშაობისას ავტორი ეყრდნობოდა საქართველოს ისტორიის წყაროებსა და ქართველ მეცნიერთა (მათ შორის საკუთარ) გამოკვლევებს. ნაშრომი განკუთვნილია მკითხველთა ფართო წრისათვის. ISBN99928-71-59-8 © George Anchabadze, 2005 © გიორგი ანჩაბაძე, 2005 3 Early Ancient Georgia (till the end of the IV cen. B.C.) Existence of ancient human being on Georgian territory is confirmed from the early stages of anthropogenesis. Nearby Dmanisi valley (80 km south-west of Tbilisi) the remnants of homo erectus are found, age of them is about 1,8 million years old. At present it is the oldest trace in Euro-Asia. Later on the Stone Age a man took the whole territory of Georgia. Former settlements of Ashel period (400–100 thousand years ago) are discovered as on the coast of the Black Sea as in the regions within highland Georgia. Approximately 6–7 thousands years ago people on the territory of Georgia began to use as the instruments not only the stone but the metals as well. -

Akhalgori Deadlock

Contributor to the publication: Giorgi Kanashvili Responsible for the publication: Ucha Nanuashvili English text editor: Vikram Kona Copyrights: Democracy Research Institute (DRI) This report is developed by the Democracy Research Institute (DRI), within the project Supporting Human Rights Protection at Front Line, with the financial support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The project aims at protecting human rights in conflict- affected territories which, among others, implies monitoring of the situation in terms of human rights protection to fill information lacunae. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the position of the EED. Tbilisi 2021 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 4 THE CONTEXT: GEORGIAN-OSSETIAN RELATIONS SINCE 2008 ....................................... 4 THE SITUATION OF THE POPULATION OF AKHALGORI BEFORE THE CHORCHANA- TSNELISI CRISIS ............................................................................................................................... 6 THE CHORCHANA-TSNELISI CRISIS AND CREEPING ETHNIC CLEANSING IN AKHALGORI ........................................................................................................................................ 8 THE FUTURE OF THE POPULATION OF AKHALGORI AND THE POLICY TO BE PURSUED BY GEORGIAN AUTHORITIES ................................................................................ 10 03 INTRODUCTION