Georgia and the European Charter for Regional And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON the EFFECTIVE USE of PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Andrew Peek All Rights Reserved

ON THE EFFECTIVE USE OF PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 2021 Andrew Peek All rights reserved Abstract This dissertation asks a simple question: how are states most effectively conducting proxy warfare in the modern international system? It answers this question by conducting a comparative study of the sponsorship of proxy forces. It uses process tracing to examine five cases of proxy warfare and predicts that the differentiation in support for each proxy impacts their utility. In particular, it proposes that increasing the principal-agent distance between sponsors and proxies might correlate with strategic effectiveness. That is, the less directly a proxy is supported and controlled by a sponsor, the more effective the proxy becomes. Strategic effectiveness here is conceptualized as consisting of two key parts: a proxy’s operational capability and a sponsor’s plausible deniability. These should be in inverse relation to each other: the greater and more overt a sponsor’s support is to a proxy, the more capable – better armed, better trained – its proxies should be on the battlefield. However, this close support to such proxies should also make the sponsor’s influence less deniable, and thus incur strategic costs against both it and the proxy. These costs primarily consist of external balancing by rival states, the same way such states would balance against conventional aggression. Conversely, the more deniable such support is – the more indirect and less overt – the less balancing occurs. -

Tales of the Narts: Ancient Myths and Legends of the Ossetians

IntRODUctION THE OSSETIAN EpIC “TALES OF THE NARTS” VASILY IvANOVICH ABAEV 1 w CYCLES, SubjECTS, HEROES In literary studies it is established that the epic poem passes through sev- eral stages in its formation. To begin we have an incomplete collection of stories with no connections between them, arising in various centers, at various times, for various reasons. That is the first stage in the formation of the epic. We cannot as yet name it such. But material is in the process of preparation that, given favorable conditions, begins to take on the out- lines of an epic poem. From the mass of heroes and subjects a few favorite names, events, and motifs stand out, and stories begin to crystallize around them, as centers of gravity. A few epic centers or cycles are formed. The epic enters the second stage of cycle formation. In a few instances, not all by any means, it may then attain a third stage. Cycles up to now unconnected may be, more or less artificially, united in one thematic thread, and are brought together in one consistent story, forming one epic poem. A hyper- cyclic formation, if one can use such a term, takes place. It may appear as the result of not only uniting several cycles, but as the expansion of one favorite cycle, at the expense of others less popular. This is the concluding epic phase. The transformation to this phase is frequently the result of individual creative efforts. For instance, the creation of the Iliad and the Odyssey Opposite page: A beehive tomb from the highlands of North Ossetia. -

Tbilisi As a Center of Crosscultural Interactions (The 19Th– Early 20Thcenturies)

Khazar Journal Of Humanities and Social Sciences Special Issue, 2018 ©Khazar University Press, 2018 DOI: 10.5782/kjhss.2018.233.252 Tbilisi as a Center of Crosscultural Interactions (The 19th– early 20thCenturies) Nino Chikovani Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia The city of Tbilisi – the capital of Georgia, during its long period of existence, has been an interesting place of meeting and interaction of different cultures. In this context, the present paper deals with one of the most interesting periods in the history of the city. From the beginning of the 19th century, when the establishment of the Russian imperial rule started in the Caucasus, Tbilisi became an official political center of the region; political and economic changes, occurring during the second half of the 19th century, significantly influenced ethnic and religious composition of Tbilisi, its cultural lifetime and mode of life in general. For centuries-long period, Tbilisi, like other big cities (how much big does not matter in this case), was not only the Georgian city in ethnic terms; but also, it represented a blend of different religious and ethnic groups. Not only in a distant past, but just a couple of decades ago, when the phenomenon of the so called ‘city yards’ (which are often called as ‘Italian yards’ and which have almost disappeared from the city landscape) still existed in Tbilisi, their residents spoke several languages fluently. Ethnically and religiously mixed families were not rare. Such type of cities, termed as Cosmo-policies by some researchers, has an ability to transform a visitor, at least temporarily, into a member of “in-group”, in our case – into Tbilisian. -

RUSSIAN ORIENTAL STUDIES This Page Intentionally Left Blank Naumkin-Los.Qxd 10/8/2003 10:33 PM Page Iii

RUSSIAN ORIENTAL STUDIES This page intentionally left blank naumkin-los.qxd 10/8/2003 10:33 PM Page iii RUSSIAN ORIENTAL STUDIES Current Research on Past & Present Asian and African Societies EDITED BY VITALY NAUMKIN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 naumkin-los.qxd 10/8/2003 10:33 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Current research on past & present Asian and African societies : Russian Oriental studies / edited by Vitaly Naumkin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13203-1 (hard back) 1. Asia—Civilization. 2. Africa—Civilization. I. Title: Current research on past and present Asian and African societies. II. Naumkin, Vitalii Viacheslavovich. DS12.C88 2003 950—dc22 2003060233 ISBN 90 04 13203 1 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change printed in the netherland NAUMKIN_f1-v-x 11/18/03 1:27 PM Page v v CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ vii PART ONE POLITICS AND POWER Monarchy in the Khmer Political Culture .............................. 3 Nadezhda Bektimirova A Shadow of Kleptocracy over Africa (A Theory of Negative Forms of Power Organization) ... -

Ethnic Processes in Shida Karthli (The Ossetians in Georgia)

Ethnic Processes in Shida Karthli (The Ossetians in Georgia) Roland Topchishvili Short survey about the ethnic situation in Georgia Georgia has never been a mono-ethnic state. Drastic changes in the ethnic situation occurred due to the annexation of Georgia by Russia (1801). It was the purposeful politics of Tsarism to colonize a state with different ethnic groups, usually notwithstanding the will of the peoples, who had to transmigrate from their native lands. Besides, Tsarist Russia did not allow local population to exile to another place and did everything to force them leave their native lands (Abkhazian and Georgian Muslims exiling to Turkey for instance). The percentage of Georgians diminished constantly when it became a constituent of the Russian Empire. At the beginning of the 19. century, 90 % of the whole population were Georgians; By 1939, it diminished to 61 %. In the 19. century, ethnic Armenians, Greeks were resettled from the Osman Empire to Georgia and Russians and Germans. Earlier, Armenians settled in Georgia, basically in towns. Two strata of Armenians were distinguished: a) migrants and b) Georgian monophysists, nominated as Armenians. Georgian language was the mother tongue of both strata. They created books and documents in Georgian. The Jews living in Georgia called themselves “Georgian Jews”, and differed from Georgians by religion. The Tatars (ancestors of modern Azeri) from Borchalo were respectful citizens of Georgia. They were devoted to the Georgian Kings and especially showed themselves under the reign of King Erekle II. A worthy man was warrior Khudia Borchaloeli, who actually became a national hero of Georgia. The Abkhazian and Ossetian peoples Before dealing with the principle issue – the migration of the Ossetians to Georgia and Georgian-Ossetians interrelations - it should be mentioned that Georgian-Abkhazian and Georgian-Ossetians relations (notwithstanding the facts of former forays from the North Caucasus) were friendly and neighborly, before their purposeful transmigration from the North Caucasus by the Russian empire. -

Download Download

Pre-Soviet and contemporary contexts of the dialogue of Caucasian cultures and identities Magomedkhan Magomedkhanov and Saida Garunova The article is devoted to problematic issues in the description of the Caucasian ethnicities and common Caucasian identities in the context of Pre-Soviet and contemporary history of the dialogue of cultures. It is noted that a comprehensive philosophical interpretation of the concept of Caucasian identity can hardly claim to universality and a satisfactory shared perception of social scientists, representing different fields of science. With regard to the actual problems of knowledge of Caucasian identity, the author proposes to use the appropriate traditional Caucasian scale of values of the semantic and semiotic transcriptions of Caucasian reality. Effect of 19th and 20th century history on Caucasian cultures Far from being isolated from the world, Caucasian civilization represents a remarkable fusion of the Arabic, Turkic, Iranian, Jewish, Greek and Slavic cultures. A reflection of the mingling of indigenous and Eurasian traditions during many centuries can be observed in the cultural characteristics of the Caucasian peoples, particularly in their material culture. The history of the Caucasus may be observed as a permanent dialogue of cultures and civilizations. The dialogue was – and continues to be – always lively, sometimes peaceful, from time to time dramatic, and fruitful. For example, during the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, when Tiflis became the administrative, cultural and scientific capital of the Caucasus, and Baku the economic center. The Caucasus from recorded history is an integral cultural space. The natural development of Caucasian civilization was supported by political and trade-economic ties within the Caucasus and with the outside world. -

The Politics of a Name : Between Consolidation and Separation in the Northern Caucasus

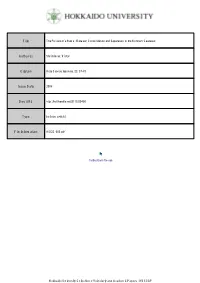

Title The Politics of a Name : Between Consolidation and Separation in the Northern Caucasus Author(s) Shnirelman, Victor Citation Acta Slavica Iaponica, 23, 37-73 Issue Date 2006 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/39456 Type bulletin (article) File Information ASI23_002.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Acta Slavica Iaponica, Tomus 23, pp. 37-73 The Politics of a Name: Between Consolidation and Separation in the Northern Caucasus* Victor Shnirelman “Whatever has been fixed by a name, Henceforth is not only real, but is a Reality.” Ernst Cassirer The abrupt growth of nationalism in the very late 20th – very early 21st cen- turies manifested itself in particular in the intense discussions of ethnic names and their changes to meet the vital demands of ethnic groups or their elites.1 A search for a new identity did not escape the Northern Caucasus,2 which dem- onstrated the “magical power of words,” singled out by Pierre Bourdieu. For him, a demonstration of name is “the typically magical act through which the particular group – virtual, ignored, denied, or repressed – makes itself visible and manifests, for other groups and for itself, and attests to its existence as a group that is known and recognized...”3 Long ago, Ernst Cassirer and, after ∗ I wish to thank the Slavic Research Center of the Hokkaido University for support of this research. I would also like to express my thanks to Moshe Gammer and two anonymous reviewers for their many useful comments and suggestions on this article. 1 Donald L. -

(Moscow) Alanica Bilingua: Sources Vs. Archaeology. the Case of East and West Alania 2

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS *Not available abstracts 1. Alemany, Agusti (Barcelona) - Arzhantseva, Irina (Moscow) Alanica Bilingua: Sources vs. Archaeology. The Case of East and West Alania 2. *Bais, Marco (Bologna-Roma) Alans in Armenian Sources after the 10th c. A.D. 3. Balakhvantsev, Archil (Moscow) The Date of the Alans' First Appearance in Eastern Europe 4. *Baratin, Charlotte (Paris) Le renouvellement des élites iraniennes au sud de l'Hindukush au premier siecle avant notre ere: Sakas ou Bactriens? 5. Bezuglov, Sergej (Rostov-na-Donu) La Russie meridionale et l'Espagne: a propos des contacts au début de l' époque des migrations 6. Borjian, Habib (Tehran) Looking North from the Lofty Iranian Plateau: a Persian View of Steppe Iranians 7. Bzarov, Ruslan (Vladikavkaz) The Scytho-Alanic Model of Social Organization (Herodotus' Scythia, Nart Epic and Post-Medieval Alania) 8. Canepa, Matthew (Charleston) The Problem of Indo-Scythian Art and Kingship: Evolving Images of Power and Royal Identity between the Iranian, Hellenistic and South Asian Worlds 9. Cheung, Johnny (Leiden) On Ossetic as the Modern Descendant of Scytho- Sarmato-Alanic: a (Re)assessment 10. Dzitstsojty, Jurij (Vladikavkaz) A Propos of Modern Hypotheses on the Origin of the Scythian Language 11. Erlikh, Vladimir (Moscow) Scythians in the Kuban Region: New Arguments to the Old Discussion 12. Fidarov, Rustem (Vladikavkaz) Horse Burials in the Zmejskaja Catacomb Burial Place 13. Gabuev, Tamerlan (Moscow) The Centre of Alanic Power in North Ossetia in the 5th c. A.D. 14. Gagloev, Robert (Tskhinvali) The Sarmato-Alans and South Ossetia 15. Gutnov, Feliks (Vladikavkaz) The Genesis of Feudalism in the North Caucasus 16. -

Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS DE ATTILA JÓZSEF NOMINATAE ACTA ANTIQUA ET ARCHAEOLOGICA Tomus XIII. KISEBB DOLGOZATOK a klasszika-filológia és a régészet köréből MINORA OPERA ad philologiam classicam et archaeologiam pertinentia ΧΠΙ. J. HARMATTA STUDIES IN THE HISTORY AND LANGUAGE OF THE SARMATIANS Szeged 1970 CONTENTS PREFACE 4 I. THE WESTERN SARMATIANS IN THE NORTH PONTIC REGION 1. From the Cimmerii up to the Sarmatians 7 2. Strabo's Report on the Western Sarmatian Tribal Confederacy 12 3. Late Scythians and Sarmatians. The Amage Story 15 4. The Western Sarmatian Tribal Confederacy and the North Pontic Greek Cities 20 5. Mithridates VI and the Sarmatians 23 6. The Sarmatians on the Lower Danube 26 7. Chronology of the Rise and Falj of the Western Sarmatian Tribal Confederacy 29 8. The Sarmatians and the Yiieh-chih Migration 31 9. The Sarmatian Phalerae and Their Eastern Relations 34 10. Conclusions 39 II. THE SARMATIANS IN HUNGARY 1. The Immigration into Hungary of the Iazyges 41 2. The Iazyges and the Roxolani 45 3. Goths and Roxolani 48 4. The Disappearance of the Roxolani 49 5. The Immigration into Hungary of the Roxolani 51 6. The Evacuation of Dacia and the Roxolani 53 7. The Fall of the Sarmatians in Hungary 55 III. THE LANGUAGE OF THE SARMATIANS 1. A History of the Problem 58 2. Proto-Iranian and Ossetian 69 3. The Sarmatian Dialects of the North Pontic Region 76 4. Conclusions 95 APPENDIX I. ADDITIONAL NOTES 98 APPENDIX II. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 108 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Ill INDEX 113 3 PREFACE Since the publication of my "Studies on the History of the Sarmatians" (Buda- pest 1950. -

Minority-Language Related Broadcasting and Legislation in the Osce

MINORITY-LANGUAGE RELATED BROADCASTING AND LEGISLATION IN THE OSCE Programme in Comparative Media Law and Policy (PCMLP), Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, Wolfson College, Oxford University & Institute for Information Law (IViR), Universiteit van Amsterdam Study commissioned by the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities April 2003 Edited by: Tarlach McGonagle (IViR) Bethany Davis Noll (PCMLP) Monroe Price (PCMLP) Table of contents Acknowledgements................................................................................................................ i Overview .............................................................................................................................. 1 Suggested further reading.....................................................................................................32 Summary of international and national provisions................................................................35 Albania ................................................................................................................................56 Andorra ...............................................................................................................................62 Armenia...............................................................................................................................66 Austria.................................................................................................................................71 Azerbaijan ...........................................................................................................................84 -

Linguistic Diversity and Coexistence: Experience of Spain and Russia by Lilia V

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: G Linguistics & Education Volume 21 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2021 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Linguistic Diversity and Coexistence: Experience of Spain and Russia By Lilia V. Moiseenko & Fatima R. Biragova Moscow State Linguistic University Abstract- The article examines the contacting languages in regional bilingual environments and their role in the preservation of national identity and national culture in multinational states. Using the example of the regional languages of Spain that have received the status of co-official languages (Basque, Catalan, Galician, Aran and Valencian), the linguistic situation in autonomous entities, the peculiarities of bilingualism and the types of language conflicts are studied. The selected parameters are used to describe the linguistic situation in the Republic of North Ossetia-Alania. The article concludes about the status of the Ossetian language, the dominant role of the Russian language, and the unbalanced linguistic situation1. The formation of national – Ossetian – identity should take place in the three-dimensional space of national, all- Russian and world culture. Keywords: contacting languages; bilingual environments; co-official languages; linguistic situation; language conflicts; national identity. GJHSS-G Classification: FOR Code: 200499 LinguisticDiversityandCoexistenceExperienceofSpainandRussia Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2021. Lilia V. Moiseenko & Fatima R. Biragova. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

COST of CONFLICT: UNTOLD STORIES Georgian-Ossetian Conflict in Peoples’ Lives

COST OF CONFLICT: UNTOLD STORIES Georgian-Ossetian Conflict in Peoples’ Lives 2016 Editors: Dina Alborova, Susan Allen, Nino Kalandarishvili Publication Manager: Margarita Tadevosyan Circulation: 100 © George Mason University CONTENTS COMMENTS FROM THE EDITORS Dina Alborova, Susan Allen, Nino Kalandarishvili ................................5 Introduction to Georgian stories Goga Aptsiauri ........................................................................................9 Georgian untold stories ........................................................................11 Intorduction to South Ossetian stories Irina Kelekhsaeva ...................................................................................55 South Ossetian untold stories ...............................................................57 3 COMMENTS FROM THE EDITORS “Actual or potential conflict can be resolved or eased by appealing to common human capabilities to respond to good will and reasonableness”1 The publication you are holding is “Cost of Conflict: Untold Sto- ries-Georgian-Ossetian Conflict in Peoples’ Lives.” This publication fol- lows the collection of analytical articles “Cost of Conflict: Core Dimen- sions of Georgian-South Ossetian Context.” This collection brings together personal stories told by people who were directly affected by the conflict and who continue to pay a price for the conflict today. In multilayered analysis of the conflict and of ways of its resolution the analysis of the human dimension is paid much less attention. This subse- quently