The Kana Crash Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Old Documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu

NINJAL International Symposium 2018 Approaches to Endangered Languages in Japan and Northeast Asia, August 6-8 The study of old documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu: Promise and Challenges Tomomi Sato (Hokkaido U) & Anna Bugaeva (TUS/NINJAL) [email protected] [email protected]) Introduction: Ainu • AINU (isolate, North Japan, moribund) • Is the only non-Japonic lang. of Japan. • Major dialect groups : Hokkaido (moribund), Sakhalin (extinct since 1993), Kuril (extinct since the end of XIX). • Was also spoken in Tōhoku till mid XVIII. • Hokkaido Ainu dialects: Southwestern (well documented) Northeastern (less documented) • Is not used in daily conversation since the 1950s. • Ethnical Ainu: 100,000. 2 Fig. 2 Major language families in Northeast Asia (excluding Sinitic) Amuric Mongolic Tungusic Ainuic Koreanic Japonic • Ainu shares only few features with Northeast Asian languages. • Ainu is typologically “more like a morphologically reduced version of a North American language.” (Johanna Nichols p.c.). • This is due to the strongly head-marking character of Ainu (Bugaeva, to appear). Why is it important to study Ainu? • Ainu culture is widely regarded as a direct descendant of the Jōmon culture which was spread in the Japanese archipelago in the Prehistoric time from about 14,000 BC. • Ainu is the only surviving Jōmon language; there had been other Jōmon lgs too: about 300 lgs (Janhunen 2002), cf. 10 lgs (Whitman, p.c.) . • Ainu is likely to be much more typical of what languages were like in Northeast Asia several millennia ago than the picture we would get from Chinese, Japanese or Korean. • Focusing on Ainu can help us understand a period of northeast Asian history when political, cultural and linguistic units were very different to what they have been since the rise of the great historically-attested states of East Asia. -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

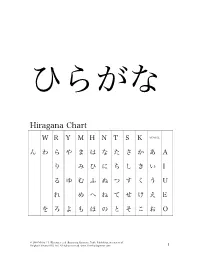

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Como Digitar Em Japonês 1

Como digitar em japonês 1 Passo 1: Mudar para o modo de digitação em japonês Abra o Office Word, Word Pad ou Bloco de notas para testar a digitação em japonês. Com o cursor colocado em um novo documento em algum lugar em sua tela você vai notar uma barra de idiomas. Clique no botão "PT Português" e selecione "JP Japonês (Japão)". Isso vai mudar a aparência da barra de idiomas. * Se uma barra longa aparecer, como na figura abaixo, clique com o botão direito na parte mais à esquerda e desmarque a opção "Legendas". ficará assim → Além disso, você pode clicar no "_" no canto superior direito da barra de idiomas, que a janela se fechará no canto inferior direito da tela (minimizar). ficará assim → © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 2: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em japonês Se você não consegue ler em japonês, pode mudar a exibição da barra de idioma para inglês. Clique em ツール e depois na opção プロパティ. Opção: Alterar a barra de idiomas para exibir em inglês Esta janela é toda em japonês, mas não se preocupe, pois da próxima vez que abrí-la estará em Inglês. Haverá um menu de seleção de idiomas no menu de "全般", escolha "英語 " e clique em "OK". © 2017 Fundação Japão em São Paulo Passo 3: Digitando em japonês Certifique-se de que tenha selecionado japonês na barra de idiomas. Após isso, selecione “hiragana”, como indica a seta. Passo 4: Digitando em japonês com letras romanas Uma vez que estiver no modo de entrada correto no documento, vamos digitar uma palavra prática. -

The Twentieth-Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and Its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic

Journal of World Literature 1 (2016) 275–293 brill.com/jwl The Twentieth-Century Secularization of the Sinograph in Vietnam, and its Demotion from the Cosmological to the Aesthetic John Duong Phan* Rutgers University [email protected] Abstract This article examines David Damrosch’s notion of “scriptworlds”—spheres of cultural and intellectual transfusion, defined by a shared script—as it pertains to early mod- ern Vietnam’s abandonment of sinographic writing in favor of a latinized alphabet. The Vietnamese case demonstrates a surprisingly rapid readjustment of deeply held attitudes concerning the nature of writing, in the wake of the alphabet’s meteoric suc- cesses. The fluidity of “language ethics” in early modern Vietnam (a society that had long since developed vernacular writing out of an earlier experience of diglossic liter- acy) suggests that the durability of a “scriptworld” depends on the nature and history of literacy in the societies under question. Keywords Vietnamese literature – Vietnamese philology – Chinese philology – script reform – language reform – early modern East Asia/Southeast Asia Introduction In 1919, the French-installed emperor Khải Định permanently dismantled Viet- nam’s civil service examinations, and with them, an entire system of political * I would like to thank Wynn Wilcox, Nguyễn Tuấn Cường, Tuna Artun, and Jack Chia for their valuable help and input. All errors are my own. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/24056480-00102010 Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 07:54:41AM via free access 276 phan selection based on proficiency in Literary Sinitic.1 That same year, using a con- troversial latinized alphabet called Quốc Ngữ (lit. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Android Apps for Learning Kana Recommended by Our Students

Android Apps for learning Kana recommended by our students [Kana column: H = Hiragana, K = Katakana] Below are some recommendations for Kana learning apps, ranked in descending order by our students. Please try a few of these and find one that suits your needs. Enjoy learning Kana! Recommended Points App Name Kana Language Description Link Listening Writing Quizzes English: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/jpn/id739.html English, Developed by the Japan Foundation and uses Hiragana Memory Hint H Indonesian, 〇 〇 picture mnemonics to help you memorize Indonesian: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id746.html Thai Hiragana. Thai: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id773.html English: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id743.html English, Developed by the Japan Foundation and uses Katakana Memory Hint K Indonesian, 〇 〇 picture mnemonics to help you memorize Indonesian: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id747.html Thai Katakana. Thai: https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id775.html A holistic app that can be used to master Kana Obenkyo H&K English 〇 〇 fully, and eventually also for other skills like https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id602.html Kanji and grammar. A very integrated quizzing system with five Kana (Hiragana and Katakana) H&K English 〇 〇 https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/jpn/id626.html varieties of tests available. Uses SRS (Spatial Repetition System) to help Kana Town H&K English 〇 〇 https://nihongo-e-na.com/android/eng/id845.html build memory. Although the app is entirely in Japanese, it only has Hiragana and Katakana so the interface Free Learn Japanese Hiragana H&K Japanese 〇 〇 〇 does not pose a problem as such. -

Machine Transliteration (Knight & Graehl, ACL

Machine Transliteration (Knight & Graehl, ACL 97) Kevin Duh UW Machine Translation Reading Group, 11/30/2005 Transliteration & Back-transliteration • Transliteration: • Translating proper names, technical terms, etc. based on phonetic equivalents • Complicated for language pairs with different alphabets & sound inventories • E.g. “computer” --> “konpyuutaa” 䜷䝷䝗䝩䜪䝃䞀 • Back-transliteration • E.g. “konpyuuta” --> “computer” • Inversion of a lossy process Japanese/English Examples • Some notes about Japanese: • Katakana phonetic system for foreign names/loan words • Syllabary writing: • e.g. one symbol for “ga”䚭䜰, one for “gi”䚭䜲 • Consonant-vowel (CV) structure • Less distinction of L/R and H/F sounds • Examples: • Golfbag --> goruhubaggu 䜸䝯䝙䝔䝇䜴 • New York Times --> nyuuyooku taimuzu䚭䝏䝩䞀䝬䞀䜳䚭䝃䜨䝤䜾 • Ice cream --> aisukuriimu 䜦䜨䜽䜳䝮䞀䝤 The Challenge of Machine Back-transliteration • Back-transliteration is an important component for MT systems • For J/E: Katakana phrases are the largest source of phrases that do not appear in bilingual dictionary or training corpora • Claims: • Back-transliteration is less forgiving than transliteration • Back-transliteration is harder than romanization • For J/E, not all katakana phrases can be “sounded out” by back-transliteration • word processing --> waapuro • personal computer --> pasokon Modular WSA and WFSTs • P(w) - generates English words • P(e|w) - English words to English pronounciation • P(j|e) - English to Japanese sound conversion • P(k|j) - Japanese sound to katakana • P(o|k) - katakana to OCR • Given a katana string observed by OCR, find the English word sequence w that maximizes !!!P(w)P(e | w)P( j | e)P(k | j)P(o | k) e j k Two Potential Solutions • Learn from bilingual dictionaries, then generalize • Pro: Simple supervised learning problem • Con: finding direct correspondence between English alphabets and Japanese katakana may be too tenuous • Build a generative model of transliteration, then invert (Knight & Graehl’s approach): 1. -

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document Proposal for the Generation Panel for the Chinese Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information Chinese script is the logograms used in the writing of Chinese and some other Asian languages. They are called Hanzi in Chinese, Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean. Since the Hanzi unification in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the most important change in the Chinese Hanzi occurred in the middle of the 20th century when more than two thousand Simplified characters were introduced as official forms in Mainland China. As a result, the Chinese language has two writing systems: Simplified Chinese (SC) and Traditional Chinese (TC). Both systems are expressed using different subsets under the Unicode definition of the same Han script. The two writing systems use SC and TC respectively while sharing a large common “unchanged” Hanzi subset that occupies around 60% in contemporary use. The common “unchanged” Hanzi subset enables a simplified Chinese user to understand texts written in traditional Chinese with little difficulty and vice versa. The Hanzi in SC and TC have the same meaning and the same pronunciation and are typical variants. The Japanese kanji were adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Finally, in Japanese, all three scripts (kanji, and the hiragana and katakana syllabaries) are used as main scripts. The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices.