„‚ Basic Communication Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

Speechreading for Information Gathering

Speechreading for information gathering: A survey of scientific sources1 Ruth Campbell Ph.D, with Tara-Jane Ellis Mohammed, Ph.D Division of Psychology and Language Sciences University College London Spring 2010 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 Questions (and answers) 3 Chronologically organised survey of tests of Speechreading (Tara Mohammed) 4 Further Sources 5 Biographical notes 6 References 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This report aims to clarify what is and is not possible in relation to speechreading, and to the development of speechreading skills. It has been designed to be used by agencies which may wish to make use of speechreading for a variety of reasons, but it focuses on requirements in relation to understanding silent speech for information gathering purposes. It provides the main evidence base for the report : Guidance for organizations planning to use lipreading for information gathering (Ruth Campbell) - a further outcome of this project. 1.2 The report is based on published, peer-reviewed findings wherever possible. There are many gaps in the evidence base. Research to date has focussed on watching a single talker’s speech actions. The skills of lipreaders have been scrutinised primarily to help improve communication between the lipreader (typically a deaf or deafened person) and the speaking hearing population. Tests have been developed to assess individual differences in speechreading skill. Many of these are tabulated below (section 3). It should be noted however that: There is no reliable scientific research data related to lipreading conversations between different talkers. There are no published studies of expert forensic lipreaders’ skills in relation to information gathering requirements (transcript preparation, accuracy and confidence). -

An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS

An Inefficient Choice: An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ted Michael Dickinson Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Jesse Fox, Advisor Dr. Brandon van der Heide Copyrighted by Ted Michael Dickinson 2012 Abstract Media richness theory is frequently cited when discussing the strengths of various media in allowing for immediate feedback, personalization of messages, the ability to use natural language, and transmission of nonverbal cues. Most studies do not, however, address the theory’s main argument that people faced with equivocal message tasks will complete those tasks faster by choosing interpersonal communication media with these features. Participants in the present study either chose or were assigned to a medium and then timed on their completion of an equivocal message task. Findings support media richness theory’s prediction; those using videoconferencing to complete the task did so in less time than those using the leaner medium of text chat. Measures of electronic propinquity, a theory proposing a sense of psychological nearness to others in a mediated communication, were also tested as a potential adjunct to media richness theory’s predictions of medium selection, with mixed results. Keywords: media richness, electronic propinquity, media selection, computer-mediated communication, nonverbal -

Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory

TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY, 14(3), 319–325 Copyright © 2005, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Digital Rhetoric: Toward an Integrated Theory James P. Zappen Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute This article surveys the literature on digital rhetoric, which encompasses a wide range of issues, including novel strategies of self-expression and collaboration, the characteristics, affordances, and constraints of the new digital media, and the forma- tion of identities and communities in digital spaces. It notes the current disparate na- ture of the field and calls for an integrated theory of digital rhetoric that charts new di- rections for rhetorical studies in general and the rhetoric of science and technology in particular. Theconceptofadigitalrhetoricisatonceexcitingandtroublesome.Itisexcitingbe- causeitholdspromiseofopeningnewvistasofopportunityforrhetoricalstudiesand troublesome because it reveals the difficulties and the challenges of adapting a rhe- torical tradition more than 2,000 years old to the conditions and constraints of the new digital media. Explorations of this concept show how traditional rhetorical strategies function in digital spaces and suggest how these strategies are being reconceived and reconfiguredDo within Not these Copy spaces (Fogg; Gurak, Persuasion; Warnick; Welch). Studies of the new digital media explore their basic characteris- tics, affordances, and constraints (Fagerjord; Gurak, Cyberliteracy; Manovich), their opportunities for creating individual identities (Johnson-Eilola; Miller; Turkle), and their potential for building social communities (Arnold, Gibbs, and Wright; Blanchard; Matei and Ball-Rokeach; Quan-Haase and Wellman). Collec- tively, these studies suggest how traditional rhetoric might be extended and trans- formed into a comprehensive theory of digital rhetoric and how such a theory might contribute to the larger body of rhetorical theory and criticism and the rhetoric of sci- ence and technology in particular. -

A Guide to Radio Communications Standards for Emergency Responders

A GUIDE TO RADIO COMMUNICATIONS STANDARDS FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS Prepared Under United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the European Commission Humanitarian Office (ECHO) Through the Disaster Preparedness Programme (DIPECHO) Regional Initiative in Disaster Risk Reduction March, 2010 Maputo - Mozambique GUIDE TO RADIO COMMUNICATIONS STANDARDS FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS GUIDE TO RADIO COMMUNICATIONS STANDARDS FOR EMERGENCY RESPONDERS Table of Contents Introductory Remarks and Acknowledgments 5 Communication Operations and Procedures 6 1. Communications in Emergencies ...................................6 The Role of the Radio Telephone Operator (RTO)...........................7 Description of Duties ..............................................................................7 Radio Operator Logs................................................................................9 Radio Logs..................................................................................................9 Programming Radios............................................................................10 Care of Equipment and Operator Maintenance...........................10 Solar Panels..............................................................................................10 Types of Radios.......................................................................................11 The HF Digital E-mail.............................................................................12 Improved Communication Technologies......................................12 -

Fact Sheet: Information and Communication Technology

Fact Sheet: Information and Communication Technology • Approximately one billion youth live in the world today. This means that approximately one person in five is between the age of 15 to 24 years; • The number of youth living in developing countries will grow by 2025, to 89.5%: • Therefore, it is a must to take youth issues into considerations in the ICT development agenda and ICT policies of each country. • For people who live in the 32 countries where broadband is least affordable – most of them UN-designated Least Developed Countries – a fixed broadband subscription costs over half the average monthly income. • For the majority of countries, over half the Internet users log on at least once a day. • There are more ICT users than ever before, with over five billion mobile phone subscriptions worldwide, and more than two billion Internet users Information and communication technologies have become a significant factor in development, having a profound impact on the political, economic and social sectors of many countries. ICTs can be differentiated from more traditional communication means such as telephone, TV, and radio and are used for the creation, storage, use and exchange of information. ICTs enable real time communication amongst people, allowing them immediate access to new information. ICTs play an important role in enhancing dialogue and understanding amongst youth and between the generations. The proliferation of information and communication technologies presents both opportunities and challenges in terms of the social development and inclusion of youth. There is an increasing emphasis on using information and communication technologies in the context of global youth priorities, such as access to education, employment and poverty eradication. -

Writing Systems Reading and Spelling

Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems LING 200: Introduction to the Study of Language Hadas Kotek February 2016 Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Outline 1 Writing systems 2 Reading and spelling Spelling How we read Slides credit: David Pesetsky, Richard Sproat, Janice Fon Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems What is writing? Writing is not language, but merely a way of recording language by visible marks. –Leonard Bloomfield, Language (1933) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and speech Until the 1800s, writing, not spoken language, was what linguists studied. Speech was often ignored. However, writing is secondary to spoken language in at least 3 ways: Children naturally acquire language without being taught, independently of intelligence or education levels. µ Many people struggle to learn to read. All human groups ever encountered possess spoken language. All are equal; no language is more “sophisticated” or “expressive” than others. µ Many languages have no written form. Humans have probably been speaking for as long as there have been anatomically modern Homo Sapiens in the world. µ Writing is a much younger phenomenon. Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems (Possibly) Independent Inventions of Writing Sumeria: ca. 3,200 BC Egypt: ca. 3,200 BC Indus Valley: ca. 2,500 BC China: ca. 1,500 BC Central America: ca. 250 BC (Olmecs, Mayans, Zapotecs) Hadas Kotek Writing systems Writing systems Reading and spelling Writing systems Writing and pictures Let’s define the distinction between pictures and true writing. -

Chapter 3 Information and Communication Technology and Its

3. INFORMATIONANDCOMMUNICATIONTECHNOLOGYANDITSIMPACTONTHEECONOMY – 51 Chapter 3 Information and communication technology and its impact on the economy This chapter examines the evolution over time of information and communication technology (ICT), including emerging and possible future developments. It then provides a conceptual overview, highlighting interactions between various layers of information and communication technology. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. ADDRESSING THE TAX CHALLENGES OF THE DIGITAL ECONOMY © OECD 2014 52 – 3. INFORMATIONANDCOMMUNICATIONTECHNOLOGYANDITSIMPACTONTHEECONOMY 3.1 The evolution of information and communication technology The development of ICT has been characterised by rapid technological progress that has brought prices of ICT products down rapidly, ensuring that technology can be applied throughout the economy at low cost. In many cases, the drop in prices caused by advances in technology and the pressure for constant innovation have been bolstered by a constant cycle of commoditisation that has affected many of the key technologies that have led to the growth of the digital economy. As products become successful and reach a greater market, their features have a tendency to solidify, making it more difficult for original producers to change those features easily. When features become more stable, it becomes easier for products to be copied by competitors. This is stimulated further by the process of standardisation that is characteristic of the ICT sector, which makes components interoperable, making it more difficult for individual producers to distinguish their products from others. -

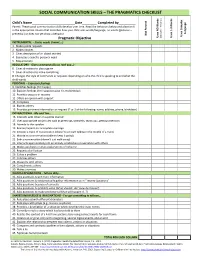

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

Interview with Philip R. Mayhew

Library of Congress Interview with Philip R. Mayhew The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PHILIP R. MAYHEW Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 26, 1995 Copyright 1998 ADST Q: I wonder if you could tell me a little bit about your background: when, where you were born and something about your family. MAYHEW: I was born in the Presidio, which is a military base in San Francisco. I lived there for the first few years of my life. Then, at a rather young age, went to the Philippines for 3 or 4 years. I think we came back about 1940. Then I grew up in Spokane, Washington and various other locations with military bases, ending in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, from which I went to college at Princeton. After Princeton I was a trainee in a Wall Street bank for a year, then in the military service, and then went to work after that for the Washington Post. Q: I'd like to go back for a minute. Was your father in the regular army? MAYHEW: Yes. Q: What was his specialty? Interview with Philip R. Mayhew http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000774 Library of Congress MAYHEW: He was an ordnance man. He was Canadian, actually, and left home after high school, not wanting to stay on the farm in Quebec. Eventually he ended up in the western United States, then joined the American army. Q: Were you tempted to join the army at all, as a career? MAYHEW: No, not really. I never had a great interest in that. -

Unit – 1 Overview of Optical Fiber Communication

www.getmyuni.com Optical Fiber Communication 10EC72 Unit – 1 Overview of Optical Fiber communication 1. Historical Development Fiber optics deals with study of propagation of light through transparent dielectric waveguides. The fiber optics are used for transmission of data from point to point location. Fiber optic systems currently used most extensively as the transmission line between terrestrial hardwired systems. The carrier frequencies used in conventional systems had the limitations in handling the volume and rate of the data transmission. The greater the carrier frequency larger the available bandwidth and information carrying capacity. First generation The first generation of light wave systems uses GaAs semiconductor laser and operating region was near 0.8 μm. Other specifications of this generation are as under: i) Bit rate : 45 Mb/s ii) Repeater spacing : 10 km Second generation i) Bit rate: 100 Mb/s to 1.7 Gb/s ii) Repeater spacing: 50 km iii) Operation wavelength: 1.3 μm iv) Semiconductor: In GaAsP Third generation i) Bit rate : 10 Gb/s ii) Repeater spacing: 100 km iii) Operating wavelength: 1.55 μm Fourth generation Fourth generation uses WDM technique. i) Bit rate: 10 Tb/s ii) Repeater spacing: > 10,000 km Iii) Operating wavelength: 1.45 to 1.62 μm Page 5 www.getmyuni.com Optical Fiber Communication 10EC72 Fifth generation Fifth generation uses Roman amplification technique and optical solitiors. i) Bit rate: 40 - 160 Gb/s ii) Repeater spacing: 24000 km - 35000 km iii) Operating wavelength: 1.53 to 1.57 μm Need of fiber optic communication Fiber optic communication system has emerged as most important communication system. -

Advancing Science Communication.Pdf

SCIENCETreise, Weigold COMMUNICATION / SCIENCE COMMUNICATORS Scholars of science communication have identified many issues that may help to explain why sci- ence communication is not as “effective” as it could be. This article presents results from an exploratory study that consisted of an open-ended survey of science writers, editors, and science communication researchers. Results suggest that practitioners share many issues of concern to scholars. Implications are that a clear agenda for science communication research now exists and that empirical research is needed to improve the practice of communicating science. Advancing Science Communication A Survey of Science Communicators DEBBIE TREISE MICHAEL F. WEIGOLD University of Florida The writings of science communication scholars suggest twodominant themes about science communication: it is important and it is not done well (Hartz and Chappell 1997; Nelkin 1995; Ziman 1992). This article explores the opinions of science communication practitioners with respect to the sec- ond of these themes, specifically, why science communication is often done poorly and how it can be improved. The opinions of these practitioners are important because science communicators serve as a crucial link between the activities of scientists and the public that supports such activities. To intro- duce our study, we first review opinions as to why science communication is important. We then examine the literature dealing with how well science communication is practiced. Authors’Note: We would like to acknowledge NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center for provid- ing the funds todothis research. We alsowant tothank Rick Borcheltforhis help with the collec - tion of data. Address correspondence to Debbie Treise, University of Florida, College of Journalism and Communications, P.O.