From Acid Revolution to Entheogenic Evolution: Psychedelic Philosophy in the Sixties and Beyond : Winner of the William M. Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being Healed: an Ethnography of Ayahuasca and the Self at the Temple of the Way of Light, Iquitos, Peru

Being Healed: An Ethnography of Ayahuasca and the Self at the Temple of the Way of Light, Iquitos, Peru DENA SHARROCK BSocSci (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology and Anthropology) School of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Newcastle December 2017 This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that the work embodied in the thesis is my own work, conducted under normal supervision. The thesis contains no material which has been accepted, or is being examined, for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 and any approved embargo. Signed: Date: 23rd December 2017 i ABSTRACT This thesis explores the experiences, articulations and meaning-making of a group of people referred to as pasajeros: middle class Westerners and people living in Western-style cultures from around the globe, who travel to the Temple of the Way of Light (‘the Temple’) in the Peruvian Amazon, to explore consciousness and seek healing through ceremonies with Shipibo ‘shamans’ and the plant medicine, ayahuasca. In the thesis, I explore the health belief systems of pasajeros, examining the syncretic space of the Temple in which Western and Eastern, New Age, biomedical, and shamanic discourses meet and intertwine to create novel sets of health beliefs, practices, and perceptions of the Self. -

A Brief History of the Women's Entheogen Fund

34 m a p s • v o l u m e x v i n u m b e r 2 • a u t u m n 2 o o 6 A Brief History of The Women’s Entheogen Fund The Women’s Entheogen Fund (WEF) nated women for funding. When Carla was created in 2002 to support the work passed away earlier this year, another Annie Harrison of women who spend a significant portion woman made a generous grant in Carla’s memory, thus expanding the pool of [email protected] of their professional lives researching psychoactive plants and chemicals. donors to the fund. Other women have While women have historically now stepped forward to make donations played a central role in investigating the in Carla’s honor and create more aware- use of entheogens, their work has been ness of the WEF. funded less frequently and has been I am very pleased to see the WEF consistently underrepresented in the community continue to grow and ac- scientific and popular entheogenic knowledge the contributions of its literature. members. I would like to thank WEF It has been especially distressing to recipients Sylvia Thyssen and Fire Erowid see relatively few female entheogenic for taking the time to document their researchers presenting their work at valuable research here in the MAPS relevant conferences over the years. This Bulletin. These women form the center of continuing disparity was illustrated once a community that I hope will continue to more at the International Symposium on support the work of female entheogenic the Occasion of the 100th Birthday of investigators–a proud and sacred tradition …as I began Albert Hofmann that took place in Basel, that stretches forward from the first wise Switzerland earlier this year. -

The Entheogens: Technology of Sacred from the Shamanic Experience

The Entheogens: technology of Sacred from the shamanic experience The term "entheogen" comes from the greek "entheos" which means "God inside". It was used for the first time by Gordon Wasson to point out those aubatances which lead the human being to recognize the divine inside themselves. We are talking about "the sacred plants" which have always been used, in the sciamanic culture, to extabilish a contact with the parallel world of spirits in order to recognize the enemies and anything which can demage the human beeing. This in its intuitive and clairvoyant powers. Regarding the entheogenic experience, interesting hypotesis have been advanced, which consider it to be the origin of religions (G. Wasson), and history of humanity could be divided into three Eras. (J. OTT). The first one is the Era of Entheogens, which had been developing itself in at least 50 millenniums, was characterized by the shamanic spiritual demostration as the entheogenic religious experience of Iron Age. This Era is considered to end with the destruction of the sanctuary of Eleusis, the last great mystery-entheogenic curt of the past. Then the Era of the Pharmacocratic Inquisition would follow. It was symbolically born in America with the fall of the Atzeca (1591) and officially set ill) in 1620 with the Spanish Inquisition, which forbade the use of "peyote" and other plants with the sauce effects, This period, which lasted over 1500 years, is characterized by the violent settlement of Christianity considered as a power of deconsecration and in open conflict with the entheogenic experience of the cult in the previous Era. -

We Chose a Different Approach Will You Support

Sign in Contribute News Opinion Sport Culture Lifestyle UK World Business Football UK politics Environment Education Society Science Tech More Mental health HuWmeph crhyo Ossem aond different Counateprinpg rscohiazocphhrenia with vitamins AbraWm Hoifflelr you Thu 26s Feub 2p004p 07o.39 rEStT it? 0 This is The Guardian’s model for open, indepTehned oeunts jtoaunrndainligs machievement of the psychiatrist Dr Humphry Osmond, who Our missionh ias sto d kieedp a ingeddep 8e6n,d leanyt jionu hrneallpisimng a tcoce isdsiebnlet itfoy e avderryeonnoec, rhergoamrdele,s as ohfa wllhuecrien tohgeeyn live or what they can afford. Fpurnoddiungce frdo min otuhre r ebardaeirns, s asfe ag ucarudsse o uorf esdcihtoizrioapl ihnrdeenpiean,d aenndce i.n It u alssion pgo vwitearsm oiunrs w toork and maintains this openness. It means more people, across the world, can access accurate information with integrity counter it. This breakthrough established the foundations for the at its heart. orthomolecular psychiatry now practised around the world. Support BThriet iGshua brdyi aonrigin, bLueta rrens midoernet in North America for more than half a century, he also saw value in the wider use of hallucinogens, whether to increase doctors' understanding of mental states; architects' appreciation of how patients perceive mental hospitals; or general imaginative and creative possibilities, notably through his association with the writer Aldous Huxley. A cultural byproduct of their exchanges was the coining of the adjective "psychedelic". Advertisement I first met Humphry in 1952, after he had emigrated with his wife Jane to become clinical director of the mental hospital in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, Canada where I was director of psychiatric research. -

The Neo-Vedanta Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.6 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed (Refereed) Journal 2019 Impact Factor (SJIF) 4.092 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE THE NEO-VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY OF SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Tania Baloria (Ph.D Research Scholar, Jaipur National University, Jagatpura, Jaipur.) doi: https://doi.org/10.33329/joell.64.19.108 ABSTRACT This paper aims to evaluate the interpretation of Swami Vivekananda‘s Neo-Vedanta philosophy.Vedanta is the philosophy of Vedas, those Indian scriptures which are the most ancient religious writings now known to the world. It is the philosophy of the self. And the self is unchangeable. It cannot be called old self and new self because it is changeless and ultimate. So the theory is also changeless. Neo- Vedanta is just like the traditional Vedanta interpreted with the perspective of modern man and applied in practical-life. By the Neo-Vedanta of Swami Vivekananda is meant the New-Vedanta as distinguished from the old traditional Vedanta developed by Sankaracharya (c.788 820AD). Neo-Vedantism is a re- establishment and reinterpretation Of the Advaita Vedanta of Sankara with modern arguments, in modern language, suited to modern man, adjusting it with all the modern challenges. In the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century many masters used Vedanta philosophy for human welfare. Some of them were Rajarammohan Roy, Swami DayanandaSaraswati, Sri CattampiSwamikal, Sri Narayana Guru, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Ramana Maharsi. Keywords: Female subjugation, Religious belief, Liberation, Chastity, Self-sacrifice. Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Copyright © 2019 VEDA Publications Author(s) agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License . -

Psychedelics and Entheogens: Implications of Administration in Medical and Non- Medical Contexts

Psychedelics and Entheogens: Implications of Administration in Medical and Non- Medical Contexts by Hannah Rae Kirk A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Biology (Honors Scholar) Presented May 23, 2018 Commencement June 2018 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Hannah Rae Kirk for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Biology presented on May 23, 2018. Title: Psychedelics and Entheogens: Implications of Administration in Medical and Non-Medical Contexts. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Robin Pappas Psychedelics and entheogens began as religious sacraments. They were apotheosized for their mind-expanding powers and were thought to open realms to the world of the Gods. It was not until the first psychedelic compound was discovered in a laboratory setting a mere hundred years ago that they entered into formal scientific study. Although they were initially well-received in academic and professional circles, research into their potential was interrupted when they were made illegal. Only recently have scientists renewed the investigation of psychedelic substances, in the hope of demonstrating their potential in understanding and healing the human mind. This thesis will explore the history of psychedelics and entheogens, consider the causes behind the prohibition of their research, and outline their reintroduction into current scientific research. Psychedelic compounds have proven to be magnifiers of the mind and, under appropriate circumstances, can act as medicaments in both therapeutic and non-medical contexts. By exploring the journey of psychedelic substances from sacraments, to therapeutic aids, to dangerous drugs, and back again, this thesis will highlight what is at stake when politics and misinformation suppresses scientific research. -

Religious Implications of Psychedelics

Religious Implications Wliarevcr rlie co~iclusion,rl~e debare ant1 rhe ~rsysl~edeliccxl)losion which ser it off, rurncd arrcnrion ro ~lleilrrriglring relarior~sliil)hcrween Psyche, Soul, and Spirit drugs and religion. Ir soon became apparenr rllar rl~ereligious uscofdrllgs to induce sacred stares of consciousness has been widesllread across nunierolrs culrures. Hisrorical examples inclt~de[he fivkco~rof 111s Greek Eleusinian nlysrcries, [he Ausrraliali al)origiries' pirirri, Hinrl~lisnisso,ir,~, Tlbrrc is a conrintlum oicosmic cnnwiousncss against which our ilidi- rhc wine ofDionysis Elcu~lrerios(Diolrysis rlie liberalor), and rlie Zoroas- viduality builds bur accidcn~aliurces and into which our wcral minds rrians' honina.4 Conrenlporary exarnplcs also abutlnd, sucli as rlie use of ylungc 3s into a nn~thersca. -William James1 marijuana hy Rastafarians alrJ some InJian yogis, Narivc American peyote, and rhe Sourh American shaniaris' ayalluasca.1 Nornarrer wliar rl~e currenr debare in rhe Wesr, ir seems clear ihar for cel~n~riesorller cl~lrl~res Psychedelics cerrainly srarrled and shook rhe \\'esrcrn world. Bur one of have agreed rliar psychedelics are capable of produci~~gvaluable religious the grearesr surprises was rhar psychedelics prnduccd religious experiences. experiences. A significanr number of people, including sraunch arheisrs and Marxisrs, claimed ro have found korsho in a capsule, mokslm in amushroom, or U~isuspccringWesterners who experi~~ie~itrdwirli rliese drugs were nor immune to rheir religious and spirirual impacr, and rhis inipacr rook rdtor; in a psychedelic. In hcr, rhcse claims proved so consisrenr over so rhree forms. The firsr was 3 spirirual iniriarion. Many people llad rheir firsr 111any years [hat some researchers have renamed psychedelics signilicar~~religious-spirirual exl~ericnceon psychedelics. -

Title Note Available from Edrs Price

DOCUMENT RESUME ED, 213 378 HE 014 886 TITLE AIR 1981-82. Forum 1981 Froceedings: Toward 2001: The IR Perspective (Minneapolis,Minnesota, May 17-20). The Association for Institutional Research Directory, 1981-82. INSTITUTION Association for Institutional Research. PUB DATE Dec 81 NOTE 281p.; Not available in papir copy due to marginal legibility of original document. AVAILABLE FROMThe Association for Institutional Research, 314 Stone Building, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL. EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Awards; Biology; *College Role; Committees; Computer Assisted Instruction; computers; Economic Factors; Educational History; Energy; *Futures (of Society); Geographic Location; Global Approach; *Higher Education; *Institutional Research; Interdisciplinary Approach; Liberal Arts; Nuclear Warfare; Organization Size (Groups); Political Influences; Population Trends; Prediction; Problem Solving; *Professional Associations; *Technology Transfer; Trend Analysis; World Affairs IDENTIFIERS *Association for Institutional Research; Bylaws ABSTRACT Proceedingo of the 1981 Association for Institutional Research (AIR) Forum and '"P. 1981-82 AIR Directory are presented in a single volume. General sel,.ton addresses and authors from the forum are as follows: "Some Possible Revolutions by 2001" (Michael Marion); "Information, the Non-Depletive Resource" (John W. Lacey); "What's Higher about Higher Education?" (Harland Cleveland); and "An Assessment of the Past-and a Look at the Future" (George Beatty, -

D-213 Contemporary Issues Collection

This document represents a preliminary list of the contents of the boxes of this collection. The preliminary list was created for the most part by listing the creators' folder headings. At this time researchers should be aware that we cannot verify exact contents of this collection, but provide this information to assist your research. UC Davis Special Collections D-213 Contemporary Issues Collection * denotes items that were not in folders BOX 1 Movement for Economic Justice US Servicemen’s Fund Leftward Anarchos Liberated Librarians’ Newsletter Social Revolutionary Anarchist Liberation (2 folders) The Catalyst (New Orleans) Liberation Support Movement Counter-Spy Maine Indian Newsletter Esperanto Many Smokes Free Student Union *Missouri Valley Socialists Youth Liberation *Southern Student Organizing Committee *Free Speech Movement National Conference for New Politics The Gate National Strike Information Center Ghetto Cobra The New Voice (Sacramento) New York Federation of Anarchists OCLAE (foldered and loose) Group Research Report Organización Contental Latino-America de Estudiantes Head & Hand Open City Press Funds for Human Rights, Inc. *The Partisan *Independent Socialist *PL Berkeley News *Indians of Alcatraz Predawn Leftist *“International Journal” (Davis) D-213 Copyright ©2014 Regents of the University of California 1 *Radicals in the Professions *The Hunger Project *Something Else! (Formerly “Radicals in *The Town Forum Community Report the Professions”) Topics The Public Eye Underground/Alternative Press The Red Mole Service/Syndicate Agitprop Zephyros Education Exchange Undercoast Oil & Wine Red Spark The Turning Point The Red Worker Tribal Messenger The Republic Twin Cities Northern Sun Alliance Resist Newsletter Time for Answers Revolution The Second Page *Revolutionary Anarchist Second City Revolutionary Marxist Caucus Newsletter Seattle Helix Rights N.E.C.L.C. -

Copyright by Noah Phillips 2012

Copyright By Noah Phillips 2012 Imperialism, Neo-colonialism and International Politics in Aldous Huxley’s Island By Noah Phillips, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Masters of English Spring 2012 Signature Page Imperialism, Neo-colonialism and International Politics in Aldous Huxley's Island By Noah Phillips This thesis of project has been accepted on behalf of the Department of English by their supervisory committee: ' Dr. Charles C. MacQuarrie Committee Member TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: Imperialism, Neo-colonialism and International Politics in Aldous Huxley’s Island…………………………………………………….…………………4 CHAPTER ONE: A Review of the Scholarship of Island………………………………………………………….7 CHAPTER TWO: International Politics and 20th Century History in Island: A Historicist Approach to Plot and Character………………………………………………..22 CHAPTER THREE: An Application of Dependency Theory and World Systems Analysis to the Political and Economic Arguments of Island………………………………………………………………...43 CHAPTER FOUR: CONCLUSIONS: Aldous Huxley, Political Philosopher, Novelist………………………….61 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………........67 3 INTRODUCTION Imperialism, Neo-colonialism and International Politics in Aldous Huxley’s Island The purpose of this thesis is to understand and analyze Aldous Huxley’s presentation of neo-colonialism in his utopian novel Island. Particular attention will be given to his portrayal of economic relations between first world powers and the third world in this novel. Furthermore, his fictional rendition of military intervention and foreign policy by the United States and Britain and the role it has played in the developing world during the 20th century will be the central focus of this thesis. Huxley’s claims and critique presented in Island of the process by which first world powers dominate international politics, world markets and peripheral economies through the use of military intervention and foreign policy will be supported by historical accounts. -

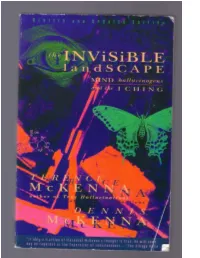

THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching

To inquire about Time Wave software in both Macintosh and DOS versions please contact Blue Water Publishing at 1-800-366-0264. fax# (503) 538-8485. or write: P.O. Box 726 Newberg, OR 97132 Passage from The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, edited by David V. Erdman. Commentary by Harold Bloom. Copyright © 1965 by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom. Published by Doubleday Company, Inc. Used by permission. THE INVISIBLE LANDSCAPE: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. Copyright © 1975, 1993 by Dennis J. McKenna and Terence K. McKenna. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. Interior design by Margery Cantor and Jaime Robles FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 BY THE SEABURY PRESS FIRST HARPERCOLLINS EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1993 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McKenna, Terence K., 1946- The Invisible landscape : mind, hallucinogens, and the I ching / Terence McKenna and Dennis McKenna.—1st HarperCollins ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-06-250635-8 (acid-free paper) 1. I ching. 2. Mind and body. 3. Shamanism. I. Oeric, O. N. II. Title. BF161.M47 1994 133—dc2o 93-5195 CIP 01 02 03 04 05 RRD(H) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 In Memory of our dear Mother Thus were the stars of heaven created like a golden chain To bind the Body of Man to heaven from falling into the Abyss. -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness.