Diane Di Prima in the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of the People Will Be Stronger Than the Pigs’ Technology”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 2017 “THE SPIRIT OF THE PEOPLE WILL BE STRONGER THAN THE PIGS’ TECHNOLOGY” An exhibition, a symposium, and a month-long series of events re-examining the interdependent legacies of revolutionary poetry and the militant left in the United States, with a spotlight on Allen Van Newkirk’s Guerrilla: Free Newspaper of the Streets (Detroit, Mich. & New York City: 1967-1968) and the recent & upcoming 50th anniversaries of the founding of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, Calif. (1966) and the White Panther Party in Detroit, Mich. (1968) including a presentation of rare ephemera from both groups. Exhibition: 9 November – 29 December 2017 @ Fortnight Institute Symposium: 17 November 2017 @ NYU Page 1 of 6 E XHIBITION A complete run of Guerrilla: Free Newspaper of the Streets serves as the focal point for an exhibition of r evolutionar y le fti s t posters , bro adsides, b oo ks, and ep hemera, ca. 196 4-197 0, a t East Villag e ( Manhattan) a rt gall e ry Fortnight Institute, opening at 6 pm on Thu rsd ay, Novemb er 9 , 2017 a nd c ontinuing through Sun day, December 29. Th e displa y also inc lude s rare, orig inal print m ate rials a nd p osters fro m the Bl ack Pan ther Party, Whi t e Panther Party , Young Lords a nd ot her revolu tion ary g roups. For t he d u ration of the exhib itio n, Fortnig ht Institute will also house a readin g room stock ed with cha pbooks and pa perbacks from leftist mili tant poets o f the era, many of w hose works we re p rinted in G uerrill a, includ ing LeRo i Jones, Diane Di P rima, M arga ret Ran dall, Reg is Deb ray an d o thers. -

POETS HATING POETRY Can’T Anyone Give Poetry a Break? by Ryan Stuart Lowe

Spring | Summer 2017 OKLAHOMA HUMANITIES Culture | Issues | Ideas dLearning to love like not hate poetry 2017—A Year of New Initiatives At Oklahoma Humanities, the will explore this challenging period in year 2017 begins with continued our nation’s history. Concurrent with the ANN THOMPSON commitment to serving the public magazine and local programming will Executive Director through inspired and inspiring cultural be the September debut of an 18-hour, experiences. In addition to successful NEH-funded Ken Burns documentary programs like Museum on Main Street; on PBS called The Vietnam War. Our Let’s Talk About it, Oklahoma; Oklahoma objective in focusing on the Vietnam era Humanities magazine; and, of course, is to remind those of us who remember our grants program; we’re working on the war to think critically of lessons special initiatives that we’re proud to learned (and not learned) from the war, bring to our state. and to inform younger generations of First, through a partnership with the challenging issues of that period the Ralph Ellison Foundation, we are that continue to impact our national sponsoring a series of public meetings identity—the civil rights movement, on race relations in Oklahoma. Using the the changing roles of women, student texts of one of Oklahoma’s most esteemed writers and favorite sons, the Foundation activism, how we treat veterans, and the will encourage community conversations roles of music, literature, television, and to foster greater understanding and to the media in forming American opinion. promote the common good. This year promises to be meaningful Second is a multi-faceted look at the and rich in opportunities and, as always, Vietnam era. -

Alexander Literary Firsts & Poetry Rare Books

CATALOGUE THIRTY-TWO Mark Alexander Alexander Rare Books 234 Camp Street ALEXANDER LITERARY FIRSTS Barre, VT 05641 Office: (802) 476-0838 & POETRY RARE BOOKS Cell: (802) 522-0257 [email protected] All items are US, UK or CN First Editions & First Printings unless otherwise stated. All items guaranteed & are fully refundable for any reason within 30 days.; orders subject to prior sale. VT residents please add 6% sales tax. Checks, money orders, most credit cards via electronic invoice (Paypal) accepted. Net so days. Libraries & institutions billed according to need. Reciprocal terms offered to the trade. Shipping is free in the US (generally via Priority Mail) & Canada; elsewhere $20 per shipment. Visit AlexanderRareBooks.com for cover scans or photos of most items. We encourage you to visit for the latest acquisitions. ------------- Due to ever increasing inventory, we will be increasing the frequency of electronic catalogues. If you receive our printed catalogues we encourage you to sign up for our electronic catalogues, also. We will continue to mail print catalogues four CATALOGUE THIRTY-TWO times a year. Electronic catalogues will include recently acquired Summer 2013 items as well as sales. Catalogue 32 5. Adam, Helen. Third Eye Shining. [San Francisco]: Intersection, 1980. First edition thus. Illustrated broadside with a poem by Adam. Designed and printed by Arion Press on Arches. Artwork by 1. A. C. D. (ed.); THE 11. Boulder, CO: Summer 1972. First edition. Adam tipped onto the broadside. One of 100 numbered and signed Stapled mimeograph magazine with a cover illustration by Charles diJulio. copies, this copy not numbered (presumably hors commerce), Printed on rectos only. -

Anne Waldman Poet, Performer, Educator on Naropa, Buddhism, and Gender

BOOKS Brenda Iijima, Eugene Marten MUSIC JOAN AS POLICE WOMAN SMALL PRESS Subpress Collective BOOG CITY POETRY Alan Semerdjian, Elizabeth Treadwell A COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FROM A GROUP OF ARTISTS AND WRITERS BASED IN AND AROUND NEW YORK CITY’S EAST VILLAGE ISSUE 17 JUNE 2004 FREE BOOG CITY Interview: Anne Waldman Poet, Performer, Educator on Naropa, Buddhism, and Gender BY GREG FUCHS she works hard at her writing. to know Waldman. nne Waldman—an inspirational, nurturing, Although Waldman made the scene on the I have visited her and revolutionary force in American eve of the summer of love, she is pre-rock-n-roll. at her house in Apoetry for four decades—still inspires She conjures up the fire and brimstone spirit the West Village, audiences to curse, tremble, and weep. that influenced early rockers like Esquerita more photographed her, When he’s done, he declares, ‘That’s a Waldman has written many books, than her 1960s contemporaries. The earth and talked to her published more by other authors with Lewis quakes and walls shake when Waldman is on about poetry. She good song,’ and heads back to his seat. Nicolaus Czarnecki photo Warsh through their press Angel Hair, directed stage. She is witness to the love and hate that is beautiful and the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church through humans wield. She testifies like a holy-rolling busy but still has its inaugural years, collaborated with visual preacher channeling the primal energy of one time to engage with artists like George Schneeman, and, with who has returned from the other side yet lived colleagues and Allen Ginsberg, started The Jack Kerouac to tell of the horrors they have seen. -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness. -

Poetics at New College of California

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2-2020 Assembling evidence of the alternative: Roots and routes: Poetics at New College of California Patrick James Dunagan University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Dunagan, Patrick James, "Assembling evidence of the alternative: Roots and routes: Poetics at New College of California" (2020). Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship. 30. https://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/30 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSEMBLING EVIDENCE OF THE ALTERNATIVE: Roots And Routes POETICS AT NEW COLLEGE OF CALIFORNIA Anthology editor Patrick James Dunagan presenting material co-written with fellow anthology editors Marina Lazzara and Nicholas James Whittington. abstract The Poetics program at New College of California (ca. 1980-2000s) was a distinctly alien presence among graduate-level academic programs in North America. Focused solely upon the study of poetry, it offered a truly alternative approach to that found in more traditional academic settings. Throughout the program's history few of its faculty possessed much beyond an M.A. -

Diane Di Prima

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit Student Exhibits 5-5-2016 Diane Di Prima McKenzie Livingston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/beat_exhibit Recommended Citation Livingston, McKenzie, "Diane Di Prima" (2016). ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit. 2. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/beat_exhibit/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Exhibits at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Livingston 1 Diane DiPrima’s Search for a Familiar Truth The image of Diane DiPrima∗ sitting on her bed in a New York flat, eyes cast down, is emblematic of the Beat movement. DiPrima sought to characterize her gender without any constraints or stereotypes, which was no simple task during the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the other Beats, who were predominately male, wrote and practiced varying degrees of misogyny, while DiPrima resisted with her characteristic biting wit. In the early days of her writing (beginning when she was only thirteen), she wrote about political, social, and environmental issues, aligning herself with Timothy Leary’s LSD Experiment in 1966 and later with the Black Panthers. But in the latter half of her life, she shifted focus and mostly wrote of her family and the politics contained therein. Her intention was to find stable ground within her familial community, for in her youth and during the height of the Beat movement, she found greater permanence in the many characters, men and women, who waltzed in and out of her many flats. -

The Berkeley Poetry Conference

THE BERKELEY POETRY CONFERENCE ENTRY FROM WIKIPEDIA: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berkeley_Poetry_Conference Leaders of what had at this time had been termed a revolution in poetry presented their views and the poems in seminars, lectures, individual readings, and group readings at California Hall on the Berkeley Campus of the University of California during July 12-24, 1965. The conference was organized through the University of California Extension Programs. The advisory committee consisted of Thomas Parkinson, Professor of English at U.C. Berkeley, Donald M. Allen, West Coast Editor of Grove Press, Robert Duncan, Poet, and Richard Baker, Program Coordinator. The roster of scheduled poets consisted of: Robin Blaser, Robert Creeley, Richard Durerden, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Joanne Kyger, Ron Lowewinson, Charles Olson, Gary Snyder, Jack Spicer, George Stanley, Lew Welch, and John Wieners. Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) did not participate; Ed Dorn was pressed into service. Seminars: Gary Snyder, July 12-16; Robert Duncan, July 12-16; LeRoi Jones (scheduled), July 19-23; Charles Olson, July 19-23. Readings (8-9:30 pm) New Poets, July 12; Gary Snyder, July 13; John Wieners, July14; Jack Spicer, July 15; Robert Duncan, July 16; Robin Blaser, George Stanley and Richard Duerden, July 17 New Poets, July 19; Robert Creeley, July 20; Allen Ginsberg, July 21; LeRoi Jones, July 22; Charles Olson, July 23; Ron Loewinsohn, Joanne Kyger and Lew Welch, July 24 Lectures: July 13, Robert Duncan, “Psyche-Myth and the Moment of Truth” July 14, Jack Spicer, “Poetry and Politics” July 16, Gary Snyder, “Poetry and the Primitive” July 20, Charles Olson, “Causal Mythology” July 21, Ed Dorn, “The Poet, the People, the Spirit” July 22, Allen Ginsberg, “What's Happening on Earth” July 23, Robert Creeley, “Sense of Measure” Readings: Gary Snyder, July 13, introduced by Thomas Parkinson. -

Beat Culture and the Grateful Dead

Beat Culture and the Grateful Dead OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did beat writers like Jack Kerouac influence the Grateful Dead’s music? OVERVIEW Note to teacher: The handout in this lesson contains descriptions of drug use. Our hope is that the language used, which quite often details the repulsive nature of addiction rather than glamorizing it, will paint a realistic, and not desirable picture of drug use. However, we suggest reviewing the handout and making a plan for using it with your classroom before working with the lesson. In post-WWII America, a radical new movement took over the literary world. Anchored by writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, the Beat Generation, as they came to be known, viewed conventional American culture with disillusionment. They embraced things like free sexuality and drug use, explorations of Eastern religion, and a shirking of materialism in favor of a liberated lifestyle. One of the era’s most definitive works, Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel On the Road, explores these themes through a semi-autobiographical road trip across America. By the 1960s, the ideals expounded by the Beats were perhaps no better exemplified in musical culture than by the Grateful Dead. For their 30-year career, the Grateful Dead embraced the liberating, always-on-the-move lifestyle promoted by works such as Kerouac’s On the Road. The band eschewed industry conventions by becoming a perpetual “road band,” gaining a reputation not through chart hits, lavish studio recordings, or flashy media appearances, but via ceaseless touring and adventurous, inclusive,and always-changing live performances. -

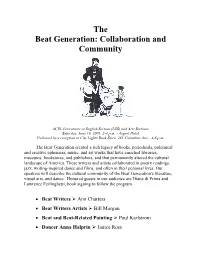

The Beat Generation: Collaboration and Community

The Beat Generation: Collaboration and Community Flores ACRL Literatures in English Section (LES) and Arts Sections Saturday, June 16, 2001, 2-4 p.m. - Argent Hotel Followed by a reception at City Lights Book Store, 261 Columbus Ave., 4-6 p.m. The Beat Generation created a rich legacy of books, periodicals, polemical and creative ephemera, music, and art works that have enriched libraries, museums, bookstores, and publishers, and that permanently altered the cultural landscape of America. These writers and artists collaborated in poetry readings, jazz, writing-inspired dance and films, and often in their personal lives. Our speakers will describe the cultural community of the Beat Generation's literature, visual arts, and dance. Honored guests in our audience are Diane di Prima and Lawrence Ferlinghetti; book signing to follow the program. • Beat Writers ¾ Ann Charters • Beat Writers Artists ¾ Bill Morgan • Beat and Beat-Related Painting ¾ Paul Karlstrom • Dancer Anna Halprin ¾ Janice Ross • Reading from His Poetry ¾ Michael McClure SPEAKERS: Dr. Charters is Professor of English, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, and an author and editor of many books inclucing The Portable Beat Reader (Viking, 1992). Dr. Karlstrom is the Director of the West Coast Research Center, Archives of American Art, Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Michael McClure is one of the original Beat poets. He continues to write and tours with musician Ray Manzarek. For more information see: http://www.thing.net/~grist/l&d/mcclure/mcclure.htm http://www.mcclure-manzarek.com/Michael-main.html. Bill Morgan is a painter, author, bibliographer, collector and the editor of Allen Ginsberg's Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays, 1952-1995 (HarperCollins, 2000) and other books on the Beat Generation. -

Beat Generation Icon William S. Burroughs Found Love – and Loved Life – During His Years in Lawrence

FOR BURROUGHS, IT ALL ADDED UP BURROUGHS CREEK TRAIL & LINEAR PARK Beat Generation icon William S. Burroughs found love – and loved life – during his years in Lawrence William S. Burroughs, once hailed by In 1943, Burroughs met Allen Ginsberg America after charges of obscenity were 11th Street Norman Mailer as “the only American and Jack Kerouac. They became fast rejected by the courts. In the meantime, novelist living today who may conceivably friends, forming the nucleus of the Burroughs had moved to Paris in 1958, be possessed by genius,” lived in Lawrence nascent Beat Generation, a group of working with artist Brion Gysin, then on a few blocks west of this spot for the last 16 often experimental writers exploring to London in 1960, where he lived for 14 13th Street years of his life. Generally regarded as one postwar American culture. years, publishing six novels. of the most influential writers of the 20th century, his books have been translated Burroughs became addicted to narcotics In 1974, Burroughs returned to 15th Street into more than 70 languages. Burroughs in 1945. The following year, he New York City where he met James was also one of the earliest American married Joan Vollmer, the roommate Grauerholz, a former University of multimedia artists; his films, recordings, of Kerouac’s girlfriend. They moved Kansas student from Coffeyville, paintings and collaborations continue to to a farm in Texas, where their son Kansas, who soon became Burroughs’ venue venue A A inspire artists around the world. He is the Billy was born. In 1948, they relocated secretary and manager. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. [ANTHOLOGY] JOYCE, James. Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers. (Edited by Robert McAlmon). 8vo, original printed wrappers. (Paris: Contact Editions Three Mountains Press, 1925). First edition, published jointly by McAlmon’s Contact Editions and William Bird’s Three Mountains Press. One of 300 copies printed in Dijon by Darantiere, who printed Joyce’s Ulysses. Slocum & Cahoon B7. With contributions by Djuna Barnes, Bryher, Mary Butts, Norman Douglas, Havelock Ellis, Ford Madox Ford, Wallace Gould, Ernest Hemingway, Marsden Hartley, H. D., John Herrman, Joyce, Mina Loy, Robert McAlmon, Ezra Pound, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams. Includes Joyce’s “Work In Progress” from Finnegans Wake; Hemingway’s “Soldiers Home”, which first appeared in the American edition of In Our Time, Hanneman B3; and William Carlos Williams’ essay on Marianne Moore, Wallace B8. Front outer hinge cleanly split half- way up the book, not affecting integrity of the binding; bottom of spine slightly chipped, otherwise a bright clean copy. $2,250.00 BERRIGAN, Ted. The Sonnets. 4to, original pictorial wrappers, rebound in navy blue cloth with a red plastic title-label on spine. N. Y.: Published by Lorenz & Ellen Gude, 1964. First edition. Limited to 300 copies. A curious copy, one of Berrigan’s retained copies, presumably bound at his direction, and originally intended for Berrigan’s close friend and editor of this book, the poet Ron Padgett.