Upland Geopolitics: Finding Zomia in Northern Laos C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory Pictures in a Time of Defeat: Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901

Hwang, Yin (2014) Victory pictures in a time of defeat: depicting war in the print and visual culture of late Qing China 1884 ‐ 1901. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/18449 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. VICTORY PICTURES IN A TIME OF DEFEAT Depicting War in the Print and Visual Culture of Late Qing China 1884-1901 Yin Hwang Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Art 2014 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

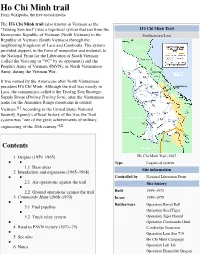

Ho Chi Minh Trail from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ho Chi Minh trail From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Hồ Chí Minh trail (also known in Vietnam as the "Trường Sơn trail") was a logistical system that ran from the Hồ Chí Minh Trail Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) to the Southeastern Laos Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) through the neighboring kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia. The system provided support, in the form of manpower and materiel, to the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (called the Vietcong or "VC" by its opponents) and the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), or North Vietnamese Army, during the Vietnam War. It was named by the Americans after North Vietnamese president Hồ Chí Minh. Although the trail was mostly in Laos, the communists called it the Trường Sơn Strategic Supply Route (Đường Trường Sơn), after the Vietnamese name for the Annamite Range mountains in central Vietnam.[1] According to the United States National Security Agency's official history of the war, the Trail system was "one of the great achievements of military engineering of the 20th century."[2] Contents 1 Origins (1959–1965) Ho Chi Minh Trail, 1967 Type Logistical system 1.1 Base areas Site information 2 Interdiction and expansion (1965–1968) Controlled by National Liberation Front 2.1 Air operations against the trail Site history 2.2 Ground operations against the trail Built 1959–1975 3 Commando Hunt (1968–1970) In use 1959–1975 Battles/wars Operation Barrel Roll 3.1 Fuel pipeline Operation Steel Tiger 3.2 Truck relay system Operation Tiger Hound Operation Commando Hunt 4 Road to PAVN victory (1971–75) Cambodian Incursion Operation Lam Son 719 5 See also Ho Chi Minh Campaign 6 Notes Operation Left Jab Operation Honorable Dragon Operation Diamond Arrow 7 Sources Project Copper Operation Phiboonpol Operation Sayasila Origins (1959–1965) Operation Bedrock Operation Thao La Parts of what became the trail had existed for centuries as Operation Black Lion primitive footpaths that facilitated trade. -

2019 FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to the Lao People's Democratic Republic

ISSN 2707-2479 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION (CFSAM) TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC 9 April 2020 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION (CFSAM) TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC 9 April 2020 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2020 Required citation: FAO. 2020. Special Report - 2019 FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8392en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISSN 2707-2479 [Print] ISSN 2707-2487 [Online] ISBN 978-92-5-132344-1 [FAO] © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). -

Gender and Social Inclusion Analysis (Gsia) Usaidlaos Legal Aid Support

GENDER AND SOCIAL INCLUSION ANALYSIS (GSIA) USAID LAOS LEGAL AID SUPPORT PROGRAM The Asia Foundation Vientiane, Lao PDR 26 July 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................... i Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................... iii 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Laos Legal Aid Support Program................................................................................................... 1 1.2 This Report ........................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Methodology and Coverage ................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Limitations ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Contextual Analysis ........................................................................................................................3 2.1 Gender Equality .................................................................................................................................. -

From 16 October 2013 to 26 January 2

Room 2 Room 1 Indochina Indochina from 1908 to 1956 from 1858 to 1907 entrance Exhibition www.musee-armee.fr - - from 16 October 2013 Open every day from 10 a.m. to 26 January 2014 to 6 p.m. until 31 October, - As of November 1st, from 10 a.m Hôtel des Invalides, to 5 p.m. 129 rue de Grenelle, Closed on 25 December and 1 January 6 boulevard des Invalides (special needs access) Paris VII Located at the crossroads of India and China, in the 16th century the Indochinese peninsula aroused European interest. The Pope gave the Jesuits and missionaries in the foreign missions the task of converting the local people and training a «native» clergy, while the initial commercial relations between Europe and the peninsula were inaugurated by the Portuguese, followed a century later by the Dutch and the English. France, which was only involved from the religious point of view in the 17th century, sought supply points between India and China for the ships belonging to the Compagnie des Indes Orientales (East India Company). The civil war of 1775-1802, coming after a relatively peaceful period between the Vietnamese domains in the North and the South, gave it the opportunity, through Mgr. Pigneau de Béhaine, of signing an assistance treaty which was never applied, between the King of France Louis XVI and the heir Sabre belonging to Gia Long, to the Nguyen dynasty, the future Emperor Gia Long (1802- the Emperor of Annam - 1820). At the same time as the Confucian structures of the Late 18th - early 19th century Steel, gold, jade, coral, pearl, Empire were being renovated, he modernised the army and precious stones and vermeil (c) Paris, Musée de l’Armée (1891). -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

08 French Energy Imperialism in Vietnam.Indd

Journal of Energy History Revue d’histoire de l’énergie AUTEUR French energy imperialism in Armel Campagne European University Vietnam and the conquest of Institute [email protected] Tonkin (1873-1885) DATE DE PUBLICATION Résumé Cet article montre que la conquête française du Vietnam a été entreprise 24/08/2020 notamment dans l'optique de l’appropriation de ses ressources en charbon, et NUMÉRO DE LA REVUE que l’impérialisme française était dans ce cas un « impérialisme énergétique ». JEHRHE #3 Il défend ainsi l’idée qu’on peut analyser la conquête française du Tonkin et SECTION de l’Annam (1873-1885) comme étant notamment le résultat d’une combinai- Dossier son des impérialismes énergétiques de la Marine, de l’administration coloniale THÈME DU DOSSIER cochinchinoise, des politiciens favorables à la colonisation et des hommes Impérialisme énergétique ? d’affaires. Au travers des archives militaires, diplomatiques et administratives et Ressources, pouvoir et d’une réinterprétation de l’historiographie existante, il explore la dynamique de environnement (19e-20e s.) l’impérialisme énergétique français au Vietnam durant la phase de conquête. MOTS-CLÉS Impérialisme, Charbon, Remerciements Géopolitique This article has benefited significantly from a workshop in November DOI 2018 of the Imperial History Working Group at the European University en cours Institute (EUI) and from the language correction of James Pavitt and Sophia Ayada of the European University Institute. POUR CITER CET ARTICLE “French colonial policy […] was inspired by […] the fact that a navy such Armel Campagne, « French as ours cannot do without safe harbors, defenses, supply centers on the energy imperialism in high seas […] The conditions of naval warfare have greatly changed […]. -

Balancing the Returns to Catchment Management: the Economic Value of Conserving Natural Forests in Sekong, Lao PDR

Balancing the Returns to Catchment Management: The Economic Value of Conserving Natural Forests in Sekong, Lao PDR Rina Maria P. Rosales, Mikkel F. Kallesoe, Pauline Gerrard, Phokhin Muangchanh, Sombounmy Phomtavong & Somphao Khamsomphou IUCN Water, Nature and Economics Technical Paper No. 5 4 Water and Nature Initiative This document was produced under the project "Integrating Wetland Economic Values into River Basin Management", carried out with financial support from DFID, the UK Department for International Development, as part of the Water and Nature Initiative of IUCN - The World Conservation Union. The designation of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of materials therein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or DFID concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication also do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, or DFID. Published by: IUCN — The World Conservation Union Copyright: © 2005, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder, providing the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of the publication for resale or for other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Citation: R. Rosales, M. Kallesoe, P. Gerrard, P. Muangchanh, S. Phomtavong and S. Khamsomphou, 2005, Balancing the Returns to Catchment Management: The Economic Value of Conserving Natural Forests in Sekong, Lao PDR. IUCN Water, Nature and Economics Technical Paper No. -

Portuguese in Shanghai

CONTENTS Introduction by R. Edward Glatfelter 1 Chapter One: The Portuguese Population of Shanghai..........................................................6 Chapter Two: The Portuguese Consulate - General of Shanghai.........................................17 ---The Personnel of the Portuguese Consulate-General at Shanghai.............18 ---Locations of the Portuguese Consulate - General at Shanghai..................23 Chapter Three: The Portuguese Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps........................24 ---Founding of the Company.........................................................................24 ---The Personnel of the Company..................................................................31 Activities of the Company.............................................................................32 Chapter Four: The portuguese Cultural Institutions and Public Organizations....................36 ---The Portuguese Press in Shanghai.............................................................37 ---The Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus...................................................39 ---The Apollo Theatre....................................................................................39 ---Portuguese Public Organizations...............................................................40 Chapter Five: The Social Problems of the Portuguese in Shanghai.....................................45 ---Employment Problems of the Portuguese in Shanghai..............................45 ---The Living Standard of the Portuguese in Shanghai.................................47 -

The Nationalist Movement in Indo-China

The Nationalist Movement in Chapter II Indo-China Vietnam gained formal independence in 1945, before India, but it took another three decades of fighting before the Republic of Vietnam was formed. This chapter on Indo-China will introduce you to one of the important states of the peninsula, namely, Vietnam. Nationalism in Indo-China developed in a colonial context. The knitting together of a modern Vietnamese nation that brought the different communities together was in part the result of colonisation but, as importantly, it was shaped by the struggle against colonial domination. If you see the historical experience of Indo-China in relation to that of India, you will discover important differences in the way colonial empires functioned and the anti-imperial movement developed. By looking at such differences and similarities you can understand the variety of ways in which nationalism has developed and shaped the contemporary world. The Nationalist Movement in Indo-China Fig.1 – Map of Indo-China. The The Nationalist Movement in Indo-China 29 1 Emerging from the Shadow of China Indo-China comprises the modern countries of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia (see Fig. 1). Its early history shows many different groups of people living in this area under the shadow of the powerful empire of China. Even when an independent country was established in what is now northern and central Vietnam, its rulers continued to maintain the Chinese system of government as well as Chinese culture. Vietnam was also linked to what has been called the maritime silk route that brought in goods, people and ideas. -

Civilizing Mission”: France and the Colonial Enterprise Patrick Petitjean

Science and the “Civilizing Mission”: France and the Colonial Enterprise Patrick Petitjean To cite this version: Patrick Petitjean. Science and the “Civilizing Mission”: France and the Colonial Enterprise. Benediky Stutchey (ed). Science Across the European Empires - 1800-1950, Oxford University Press, pp.107-128, 2005. halshs-00113315 HAL Id: halshs-00113315 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00113315 Submitted on 12 Nov 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Science and the “Civilizing Mission”: France and the Colonial Enterprise Patrick Petitjean REHSEIS (CNRS & Université Paris 7) Introduction September 1994: ORSTOM celebrated its fiftieth birthday with a conference "20th Century Sciences: Beyond the Metropolis". 1 ORSTOM (Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre-Mer) is the name given in 1953 to the former "Office de la Recherche Scientifique Coloniale," founded in 1943.2 This conference showed an evident acceptance of the colonial heritage in science and technology. Such continuities raise questions about the part played by science in the so-called second wave of European expansion of the late nineteenth century, which led to the partitioning of the world by European powers.3 The aim of this essay is to outline the part played by science in the French mission of civilisation, this “civilizing mission” and to describe how it occupied such a central part 1 The proceedings have been published. -

XSMALL Taste of Laos 06302020

BLEED MARGINS TRIM LINE SAFETYA MARGIN Taste of Laos July 16, 2020 Welcome. Thank you for joining Coffee Quality Institute for a virtual coffee tasting. This invitation-only event will introduce you to Laos' specialty coffee sector and demonstrate some of the work that is being done in Laos to improve the quality of their specialty coffee products, build relationships with farmers and producers and impact livelihoods. We are asking YOU to be part of this event because of your role in the specialty coffee industry. As a buyer, roaster or café owner (or maybe all three), you have an important role to play in “new origin” development through listening, providing feedback and asking questions. Consider this your virtual CQI Coffee Corps™ assignment! CQI is organizing this virtual coffee tasting as part of the Creating Linkages for Expanded Agricultural Networks (CLEAN) project funded by USDA and implemented by Winrock International with the Lao Department of Agriculture (DOA). CQI's good friend and Q Instructor Tim Heinze will be our able guide, and in addition to the shared experience of tasting together, you'll learn more about coffee in Laos, the CLEAN program, and you'll be able to ask questions and share opinions. This coffee kit contains 4 samples of Lao coffees, with instructions on how you can participate in the virtual tasting. These samples are a result of two CQI cupping panels, one led by Yimara Martinez Agudelo at Sustainable Harvest, and one led by our host Tim Heinze, and they were roasted for this tasting by Joe Wenbo at J Café in Portland, Oregon.