How Did Lebanese Wine Emerge As a Territorial Wine Brand in the 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

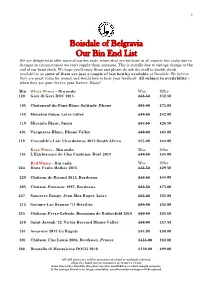

Boisdale of Belgravia Our Bin End List

1 Boisdale of Belgravia Our Bin End List We are delighted to offer some of our bin ends, wines that are brilliant in all aspects but sadly due to changes in circumstances we can’t supply them anymore. This is usually due to vintage change or the end of our bond stock. We hope you’ll enjoy them and please do ask the staff to double check availability as some of them are just a couple of last bottles available at Boisdale. We believe they are great value for money and would love to hear your feedback. All subject to availability – when they are gone they’re gone forever. Enjoy! Bin White Wines – Bin ends: Was: Offer: 120 Gavi di Gavi DOC 2015 £38.50 £32.50 105 Chateneuf-du-Pape Blanc Solitude, Rhone £95.00 £75.00 148 Menetou Salon, Loire valley £49.50 £42.00 119 Miranda Blanc, Spain £37.50 £26.50 401 Vacqueras Blanc, Rhone Valley £80.00 £65.00 118 Crocodile’s Lair Chardonnay 2013 South Africa £55.00 £44.00 Rosé Wines – Bin ends: Was Offer 181 L’Exuberance de Clos Cantenac Rosé 2015 £49.50 £45.00 Red Wines – Bin ends: Was Offer 224 Dona Paula Malbec 2015 £36.50 £29.50 229 Château de Ricaud 2012, Bordeaux £48.50 £44.00 205 Chateau Potensac 1997, Bordeaux £92.50 £75.00 227 Sancerre Rouge, Jean Max Roger, Loire £65.00 £55.00 212 Savigny Les Beaune ’11 Briailles £69.50 £58.00 255 Château Peyre-Lebade, Benjamin de Rothschild 2010 £69.50 £55.60 240 Saint Joseph ’12, Victor Berrard Rhone Valley £68.00 £57.50 251 Amarone 2013 Ca’Rugate £95.00 £80.00 291 Château Clos Louie 2006, Bordeaux, France £135.00 £82.00 268 Brunello di Montalcino DOCG 2010 £120.00 £99.00 All still wines are sold in measures of 125ml or multiples thereof. -

Wine & Drinks Menu

Wine & Drinks Menu Page Bar Drinks Aperitifs 3 Cocktails Beers Vodka Eau de Vie Liqueurs Sherry Gin 4 Whisky 5 Cognac, Armagnac, Calvados & Rum 6 Soft Drinks 7 Tea & Coffee 8 Wine List By the Glass & Carafe 10 Champagne & Sparkling Wines 11 White Wine England 12 France 12-13 Spain & Portugal 14 Rest of Europe 14 North & South America 15 Australia & New Zealand 16 Japan 16 South Africa 17 Rose & Orange Wine 17 Red Wine England 18 France 18-19 Spain & Portugal 20 Rest of Europe 21 Lebanon 21 Morocco 21 North & South America 22 Australia & New Zealand 23 South Africa 23 Dessert & Fortified Wine 24 1 BAR DRINKS 2 AN APERITIF TO BEGIN…? COCKTAILS English Kir Royale; Camel Valley Brut, Blackcurrant Liquor £12 Lumière Bellini; Camel Valley Brut with Classic Peach, Gingerbread or Elderflower £12 Classic Champagne Cocktail; Pol Roger NV, Château de Montifaud Petite Fine Cognac £18 Chase Martini; Chase Vodka or Gin shaken with Dry Vermouth £12 Smoked Bloody Mary; Chase Smoked Vodka, Tomato Juice, Celery Salt, Tabasco £12 Negroni; William Chase GB Gin, Campari, Sweet Vermouth £12 Old Fashioned; Michters Small Batch, Angostura Bitters £12 Cotswolds Espresso Martini; Cotswold Distillery Espresso Infused Vodka £12 BOTTLED BEERS & CIDER Pale Ale Shepherd’s Delight – Coberley, Cheltenham 3.6%abv – 500ml £6 Premium Bitter Drover’s Return – Coberley, Cheltenham 5%abv – 500ml £6 Lager Utopian – Bow, Devon 4.7%abv – 440ml £6 White Ale Lowlander – Amsterdam, Netherlands 5%abv – 330ml £6 Gluten Free Estrella Daura Damn – Spain 5.4%abv – 330ml £5 Cider Oliver’s -

Business Guide

TOURISM AGRIFOOD RENEWABLE TRANSPORT ENERGY AND LOGISTICS CULTURAL AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES BUSINESS GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN GUIDE RENEWABLERENEWABLERENEWABLERENEWABLERENEWABLE CULTURALCULTURALCULTURALCULTURALCULTURAL TRANSPORTTRANSPORTTRANSPORTTRANSPORTTRANSPORT AGRIFOODAGRIFOODAGRIFOODAGRIFOODAGRIFOOD ANDANDAND ANDCREATIVE ANDCREATIVE CREATIVE CREATIVE CREATIVE ENERGYENERGYENERGYENERGYENERGY TOURISMTOURISMTOURISMTOURISMTOURISM ANDANDAND ANDLOGISTICS ANDLOGISTICS LOGISTICS LOGISTICS LOGISTICS INDUSTRIESINDUSTRIESINDUSTRIESINDUSTRIESINDUSTRIES GROWTH GROWTH GROWTH GROWTH GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN OPPORTUNITIES IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN THE MEDITERRANEAN ALGERIA ALGERIA ALGERIA ALGERIA ALGERIA BUILDING AN INDUSTRY PREPARING FOR THE POST-OIL PROMOTING HERITAGE, EVERYTHING IS TO BE DONE! A MARKET OF 40 MILLION THAT MEETS THE NEEDS PERIOD KNOW-HOW… AND YOUTH! INHABITANTS TO BE OF THE COUNTRY! DEVELOPED! EGYPT EGYPT EGYPT REBUILD TRUST AND MOVE EGYPT SOLAR AND WIND ARE BETTING ON THE ARAB UPMARKET EGYPT PHARAONIC PROJECTS BOOMING WORLD’S CULTURAL THE GATEWAY TO AFRICA ON THE AGENDA CHAMPION AND THE MIDDLE EAST IN ISRAEL SEARCH FOR INVESTORS ISRAEL ACCELERATE THE EMERGENCE ISRAEL TAKE-OFF INITIATED! ISRAEL OF A CHEAPER HOLIDAY COLLABORATING WITH THE THE START-UP NATION AT THE OFFER ISRAEL WORLD CENTRE OF AGRITECH JORDAN FOREFRONT OF CREATIVITY LARGE PROJECTS… AND START-UPS! GREEN ELECTRICITY EXPORTS JORDAN JORDAN IN SIGHT JORDAN -

Bon Coeur Fine Wines Ltd. ARGENTINA and CHILE 77

BON COEUR FINE WINES Your unique wine experience... Wine List 2017/18 bcfw.co.uk 01 INTRODUCTION IT’S BEEN A BUSY AND EXCITING YEAR FOR THE BON COEUR TEAM. IN THE LAST YEAR, WE WERE DELIGHTED TO BE NOMINATED BY DECANTER FOR WINE RETAILER OF THE YEAR AND ALSO IWC REGIONAL MERCHANT OF THE YEAR. AS WE START TO SPREAD OUR WINGS, STRENGTHENING OUR TEAM IN BOTH PRIVATE CLIENT AND ON-TRADE CHANNELS, WE CONTINUE TO OFFER THE VERY BEST IN WINE, SERVICE AND ADVICE. WITH ROUGH SEAS FORECAST ON THE POLITICAL HORIZON, WEAKENING OF DO COME AND SEE US AT MOOR PARK, THERE ARE EXCITING STERLING AND MOTHER NATURE DEVASTATING SOME WINE REGIONS, WE PLANS AHEAD, INCLUDING A TEMPERATURE CONTROLLED ARE LIKELY TO SEE SOME PRICE INCREASES OVER THE NEXT FEW YEARS. STORAGE WAREHOUSE AND FURTHER DEVELOPMENT OF THE HOWEVER, RECENTLY, WE HAVE BEEN BLESSED BY SOME EXCELLENT PREMISES; YOUR CONTINUED SUPPORT FOR OUR BUSINESS VINTAGES FROM ACROSS FRANCE IN 2014, 2015 AND 2016. BY WORKING AND THE TEAM IS MUCH APPRECIATED, THANK YOU. WE ALL CLOSELY WITH OUR NETWORK OF CONTACTS, FORGED OVER THE LAST 20 LOOK FORWARD TO THE JOURNEY AHEAD AND ARE PLEASED TO YEARS, WE ARE ABLE TO OFFER SOME HIGHLY SOUGHT AFTER CONTINUE TO OFFER YOU A FABULOUS CHOICE OF WINE FOR ALLOCATIONS, AN IMPRESSIVE DEPTH OF VINTAGES AND CHOICE, FOR YOU YOU TO ENJOY WITH FAMILY AND FRIENDS. THE CUSTOMER. ON THE INVESTMENT, FRONT MANY WINES HAVE INCREASED IN VALUE OVER THE LAST 10 YEARS, HENCE WE ARE SEEING IN THE WORDS OF MY DARLING WIFE, “LIFE’S TOO SHORT NOT CUSTOMERS SELLING BACK, BROKING AND TRADING WINES THROUGH TO DRINK GOOD WINE.” OUR WINE BROKING SERVICE, HEADED UP BY CHARLIE MURPHY. -

Wine Contamination with Ochratoxins: a Review

beverages Review ReviewWine Contamination with Ochratoxins: A Review Wine Contamination with Ochratoxins: A Review Jessica Gil-Serna 1,* ID , Covadonga Vázquez 1, María Teresa González-Jaén 2 ID and JessicaBelén Gil-Serna Patiño 1 ID1,*, Covadonga Vázquez 1, María Teresa González-Jaén 2 and Belén Patiño 1 1 1DepartmentDepartment of Microbiology of Microbiology III, III,Faculty Faculty of Biolo of Biology,gy, University University Complutense Complutense of Madrid, of Madrid, Jose Antonio NovaisJose 12, Antonio 28040 NovaisMadrid, 12, Spain; 28040 [email protected] Madrid, Spain; (C.V.); [email protected] [email protected] (C.V.); (B.P.) [email protected] (B.P.) 2 2DepartmentDepartment of Genetics, of Genetics, Faculty Faculty of Biology, of Biology, Univer Universitysity Complutense Complutense of Madrid, of Madrid, Jose Jose Antonio Antonio Novais Novais 12, 12, 2804028040 Madrid, Madrid, Spain; Spain; [email protected] [email protected] * *Correspondence:Correspondence: jgilsern [email protected];@ucm.es; Tel.: Tel.: +34-91-394-4969 +34-91-394-4969 Received:Received: 31 31October October 2017; 2017; Accepted: Accepted: 29 29December December 2017; 2017; Published: Published: 29 15January January 2018 2018 Abstract:Abstract: OchratoxinOchratoxin A A (OTA) isis thethe main main mycotoxin mycotoxin occurring occurring inwine. in wine. This This review review article article is focused is focusedon the on distribution the distribution of this of toxin this andtoxin its and producing-fungi its producing-fungi in grape in grape berries, berries, as well as aswell on as the on fate theof fateOTA of duringOTA during winemaking winemaking procedures. procedures. Due to itsDue toxic to its properties, toxic properties, OTA levels OTA in winelevels are in regulated wine arein regulateddifferent in countries; different therefore, countries; it is therefore, necessary toit applyis necessary control andto apply detoxification control methodsand detoxification that are also methodsdiscussed that in are this also revision. -

Getting You to Your Wine

GETTING YOU TO YOUR WINE Alejandro has taken great pleasure in putting this selection of wines together for you to enjoy; be it over a meal or sitting back and catching up with friends and family. All our family members have their favourite too. So if you're stuck for winespiration just ask someone. Contents By Style OUR WINES GROUPED BY A STRING IN THEIR BOW 1 Sparkling Wines TRADITIONAL METHOD SPARKLING WINES FROM OUR FAVORITE PRODUCERS AROUND THE WORLD Cava & Prosecco BUBBLES FROM CATALUNYA AND VENETO Champagne OUR SELECTION OF THE MOST FAMOUS SPARKLING WINE IN THE WORLD 2 White by the Glass CLASSIC AND FINE WINES BY THE GLASS AND CARAFE Rosé PINK HUES FROM SUN-KISSED SLOPES 3 Red by the Glass CLASSIC AND FINE WINES BY THE GLASS AND CARAFE Sticky CHARMING AND INDULGENT WAYS TO FINISH DINNER. DESSERT AND FORTIFIED 4 Magnums TO BE SURE THERE'S ENOUGH TO GO AROUND Fine Wine ICONIC WINES FROM RENOWNED REGIONS Whites 5 Crisp & Light Sauvignons & Aromatics Interesting & Complex Aromatics 6 Burgundy & Chardonnay Intense & Full Reds 7 Fruit Driven & Light Elegant Expressions & Rounded 8 Burgundy & Pinot Noirs Rhône & Earthy 9 Bordeaux & Cabernets Structured & Full Know where you like your wine form? Flip this menu over and you'll find these wines listed by country too. Wines by the glass are served in measures or multiples of 125ml and 175ml BUBBLES Classic Method Sparkling Bottle Classic Reserve NV Hampshire England 53.00 HATTINGLEY VALLEY Perlé 2013 Trento Italy 53.00 FERRARI Prosecco & Cava Bottle Prosecco Brut Argeo NV Veneto Italy 8.50 -

There Is a Lot More to Lebanese Wine Than Château Musar

10/17/2020 There is a lot more to Lebanese wine than Château Musar NEWS LIFE & STYLE LATEST MOST READ LISTEN IRELAND WORLD SPORT There is a lot more to Lebanese wine than Château Musar Importer Mackenway is donating all prots from Ksara wines to the Lebanese Red Cross I have always been fond of Lebanese red wines, but was very pleasantly surprised at a tasting of the textured white wines a few years ago John Wilson Follow about 4 hours ago 0 Lebanon suffered yet another man-made disaster recently when a huge explosion in Beirut killed more than 200 people and left 300,000 homeless.We can do our bit by buying a Lebanese wine. Importer Mackenway is donating all profits from the sale of Ksara wines in Ireland until the end of this year to the Lebanese Red Cross. Retailers are making contributions too. Most oenophiles will be familiar with Château Musar. However, it is a fairly recent addition to a long history of wine-making going back centuries to the time of the Phoenicians. The modern industry was started by Jesuit monks who founded Château Ksara in 1857. Under the Ottoman empire, Christians were permitted to produce wine for https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/food-and-drink/drink/there-is-a-lot-more-to-lebanese-wine-than-château-musar-1.4374522?mode=amp 1/7 10/17/2020 There is a lot more to Lebanese wine than Château Musar religious purposes. It expanded under the French mandate and remained with the order until 1973, when it was sold, as the Vatican encouraged religious orders to NEWS divest LIFE themselves & STYLE ofL AcommercialTEST M Oactivities.ST READ LISTEN IRELAND WORLD SPORT Then and now, Ksara is the largest wine producer in Lebanon, offering no fewer than 17 different wines, as well as Arak, an anise-flavoured spirit very popular in Lebanon. -

Wines by the Glass We Use Coravin Technology to Ensure Our Wines Are

Wines By The Glass We use Coravin technology to ensure our wines are delivered to you in peak condition. The list below is a tiny offering from our extensive wine list. You can request most of our wines with cork enclosure by the glass. Wines are served at 150ml (5.07) fluid ounces. PROSECCO Ruggeri Giustino B Millestimato, Prosecco Superiore Xtra Dry, Valdobbiadene DOCG 300 Awarded the Tre Bicchieri del Gambero Rosso making the Rivetti winery the only one in the world of Prosecco to be awarded the prestigious star award NV Drusian Valdobbiadene Prosecco DOCG, xtra Dry. Veneto 300 90pts Decanter Silver Mindus Vini 2015 WHITE WINES '18 Miles from Knowhere Chardonnay, Margaret River. Australia 250 Aged for 6 months in French Oak. The bouquet exhibits flinty scents of stone fruit and melon. The palate is crisp with nectarine notes combined with lemon curd and apricot undertones. Warm chicken salad, fish, pork. '18 Fattoria La Rivolta Falanghina del Sannio Campania, Italy 260 92WE. 100% Falanghina On the nose, ripe apple, honeysuckle and tropical fruit. The medium-sized bodied palate offers ripe pear, honeydew and tangerines drop candy. White meats and roasted figs, scallops, prawns and clams. '16 Petit Caus Pedradura Mass is del Garraf. Spain 260 Xarel-lo, Macabeo, Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc. Organic. Mineral scents of crushed rock and white fleshed fruit. Dry and vibrant with lively acidity and perfectly balanced. Aperitif, rice dishes, seafood, salads, semi-mature cheeses. '16 Viero Rioja. Spain 260 100% Viero From bush vines 42 to 80 years old. Fermented in French oak. Medium bodied, creamy with lemon, buttery vanilla notes with ripe pears and honey. -

EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN WINES: GREECE, TURKEY and LEBANON Greek Wine Turkish Wine

EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN WINES: GREECE, TURKEY AND LEBANON Greek wine Greece is one of the oldest wine-producing regions in the world. Greek wine had especially high prestige in Italy under the Roman Empire. In the medieval period, wines exported from Crete, Monemvasia and other Greek ports fetched high prices in northern Europe. A system of appellations was implemented to assure consumers the origins of their wine purchases. The appellation system categorizes wines as: • Onomasia Proelefsis Anoteras Poiotitos (O.P.A.P. ), i.e. an Appellation of Origin of Superior Quality • Onomasia Proelefsis Eleghomeni (O.P.E. ), i.e. a Controlled Appellation of Origin • Topikos Oinos , i.e. a Vin de pays • Epitrapezios Oinos , i.e. a Vin de table • Epitrapezios Oinos , regular table wine which usually comes in screw-top containers • Cava , more prestigious, aged "reserve" blends (minimum aging: 2 years for whites; 3 years for reds) • Retsina , a traditional wine, flavored with pine resin • The Wine regions Main wine growing regions of contemporary Greece are: Aegean Islands, Crete, Central Greece, Epirus, Ionian Islands ,Macedonia and, Peloponnese Varietals Xinomavro, a variety native to Greece and often compared to Nebbiolo due to its ability to develop complex earthy aromas with age, has the potential to unlock Greece’s full potential, according to its winemakers. A healthy bunch of Xinomavro . The heartland of this high tannin, high acid grape, whose name translates to “acid black”, lies in north west Greece, which is home to two PDO regions for Xinomavro, Amyndeon to the north and Naoussa further south. Greek winemakers in both regions have reaped success outside of Greece by blending Xinomavro with international varieties such as Syrah or Merlot to make them more marketable, however a belief that the industry’s future lies in further promoting the region’s indigenous grapes, so that they may stand alone, prevails. -

Wine Is Sunlight, Held Together by Water” Galilei

We proudly offer a selection of 1966 individual wines Our list is one of the largest wine lists in England in terms of producers, regions…diversity. Our wish is to showcase up-and-coming styles that we deem quirky and individual, whilst tipping our hat to the most reputable wine regions. We endorse the UK wine industry with the country’s largest selection of sparkling wines from across England and Wales. We take great pleasure and pride in offering 100 Dessert Wines especially selected to pair our pudding seasonal offer. The Sommelier Team is on hand to offer guidance and to serve our wines with passion and enthusiasm. We hope that you enjoy perusing our MULTI-AWARDED WINE LIST The Sommelier Team at Chewton Glen Hotel & SPA “Wine is Sunlight, held together by Water” Galilei 1 What you will find in our Wine List Some of our wines will be VG –VEGAN CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING SELECTED FOR YOU…3 THE ‘BY THE GLASS’ LIST…SELECTED BUT NOT LIMITED TO…EXPLORE THE WINE LIST… 4 VE-VEGETARIAN PUDDING WINES WITH….PUDDING AND/OR CHEESE…TIPS…5 B-BIODYNAMIC THE WINES TO MAKE YOU FEEL AT HOME…£30 LIST...6 O-ORGANIC DEAL OF THE WEEK AND BIN ENDS…7 LS-LOW SULPHUR EXPLORE THE WINE LIST….THE FINEST WINE SELECTION BY CORAVIN…8 NS-NO SULPHUR ENGLISH SPARKLINGS…LARGEST COLLECTION…09 - 10 TAITTINGER….COMTES VERTICAL & CAVIAR…11 CHAMPAGNE….THE 1995 COLLECTION…12 MOST OF OUR WINES CONTAIN SULPHITES PROSECCO AND…THE OUTSIDERS…13 - 23 PRICES ARE IN ROSE WINES & DEVONSHIRE CRAB…14 POUNDS STERLING FANCY RIESLING...15 & MUSCADET & OYSTERS…17 INCLUDE VALUE ADDED TAX CHABLIS & HALIBUT…19 REGRETTABLY THE WINES SCORED OUT IN PENCIL POUILLY-FUISSE’ & CHALKSTREAM TROUT…22 ARE CURRENTLY PINOT BIANCO & TWICE BAKED CHEESE SOUFFLE’…26 UNAVAILABLE VERMENTINO & LOBSTER CURRY…27 TRADE DESCRIPTION ACT ALBARINO & POUISSIN…29 IT IS NOT POSSIBLE TO GUARANTEE MUSKATELLER & CURED TROUT…32 CONTINUITY OF ALL VINTAGES AND PRODUCERS IN THIS LIST AND IN SOME CASES NEW ZEALAND SAUVIGNON BLANC & TUNA TATAKI…39 A SUITABLE ALTERNATIVE MAY BE SERVED. -

Ilili Beverage Menu 08.26.21.Pub

Wine has flowed throughout Lebanon’s history from ancient times to present day. In this beautiful land of antiquity, beverage, food, and people are one and the same. Our beverage program reflects this, representing the best of both Lebanese traditions and those beyond the levant, while paying special homage to underrepresented people and places which also produce beautiful drinks born from nature. The complexities of Lebanese cuisine, teamed with the culture’s singular hospitality, offer exponential possibilities for pairing and sharing. We look forward to sharing them with you. Chris Struck, Beverage Director Framed selections indicate Lebanese wineries or affiliations 2 Table of Contents Arak & Cocktail 1-2 Wine by the Glass 3 Sake, Cider, & Beer 4 Wine by the Bottle Sparkling 5-6 White Ancient World 7 Old World 8-10 New World 11 Rosé 12 Red Ancient World 13-14 Old World 14-18 New World 19-20 Large Format 21 Sweet & Fortified 22 Apero, Digestif, Amaro, & Spirit 23-24 3 Arak There are drinks to get you drunk, and there are those to be savored with food. Arak represents the latter. This smooth, refreshing spirit, noted for its profile of licorice with a hint of peppermint, cleanses the taste buds and refreshes the palate for each new dish. Arak makers also tout its holistic properties, claiming the aniseed aids in digestion and relaxation. Tradition states that Arak is not sipped straight but mixed in a ratio approximately 1/3 arak to 2/3 water, and requires that water is added before ice. Be playful and mix it yourself or allow our us to mix it for you. -

IXSIR ALTITUDES Country Lebanon. Total Area 110 Hectares. Soil Clay

IXSIR ALTITUDES Country Lebanon. Total area 110 hectares. Soil Clay-calcareous. Calcareous and stone layers. Grape varieties Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Tempranillo, Caladoc, Merlot, Viognier, Muscat, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay and Sémillon. Harvest Manual, in crates of 18kg, with a temperature control below 18 0C. ALTITUDES, IXSIR ALTITUDES, IXSIR ALTITUDES, IXSIR WHITE, 2009 ROSE, 2009 RED, 2008 Tasting This blend of four noble southern This is what we can call a wine rosé Warmth, sharpness, maturity and notes varieties presents an elegant swirl of “à la Provence”. Its marble pink robe character are the dominant traits of golden glittering robes. Breathing an with peony reflections reveal an this wine. Imprinted with mature exquisite bouquet of floral aromas intense bouquet of gooseberry and fruits, Its delicate and complex with hints of Muscat and notes of vine leaves. Its suave, fruity, crispy bouquet varies between an oaked grapefruit, this floral and fruity blend and delicate palate will be a “coup de aroma and red and black fruits. translates into a balanced and sharp folie” for anyone passionate about Notes of blackberry and blackcurrant palate hinted with spicy undertones. authentic rosé wines. blended with a fine “empyreumatic” A soft touch of acidity gives the wine touch give the wine a soft and a pleasant freshness. complex character. Its final silky taste makes it a pleasant and accessible wine, to share in a relaxed environment. Grape 40% Muscat, 30% Viognier, 15% 66% Syrah and 34% Caladoc. 35% Cabernet Sauvignon, 22% varieties Sauvignon and 15% Sémillon. Syrah, 26% Caladoc and 17% Tempranillo. .