Lewis Caroll, the Hunting of the Snark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

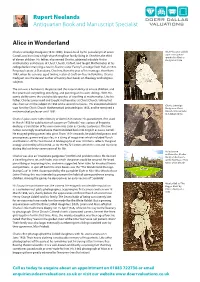

Alice in Wonderland

Rupert Neelands Antiquarian Book and Manuscript Specialist Alice in Wonderland Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898), known to all by his pseudonym of Lewis Alice Pleasance Liddell, Carroll, was born into a high-church Anglican family living in Cheshire, the third aged seven, photo- graphed by Charles of eleven children. His father, also named Charles, obtained a double first in Dodgson in 1860 mathematics and classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and taught Mathematics at his college before marrying a cousin, Frances Jane “Fanny” Lutwidge from Hull, in 1827. Perpetual curate at Daresbury, Cheshire, from the year of his marriage, then from 1843, when his son was aged twelve, rector at Croft-on-Tees in Yorkshire, Charles Dodgson was the devout author of twenty-four books on theology and religious subjects. The son was a humourist. He possessed the natural ability to amuse children, and first practised storytelling, versifying, and punning on his own siblings. With this comic ability came the unshakeable gravitas of excelling at mathematics. Like his father, Charles junior read and taught mathematics at Christ Church, taking first class honours in the subject in 1854 and a second in classics. His exceptional talent Charles Lutwidge won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855, and he remained a Dodgson at Christ mathematical professor until 1881. Church 1856-60 (John Rich Album, NPG) Charles’s jokes were rather literary or donnish in nature. His pseudonym, first used in March 1856 for publication of a poem on “Solitude”, was a piece of linguistic drollery, a translation of his own name into Latin as Carolus Ludovicus. -

PDF Download Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense: Collected Poems

JABBERWOCKY AND OTHER NONSENSE: COLLECTED POEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lewis Carroll | 464 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141195940 | English | London, United Kingdom Jabberwocky and Other Nonsense: Collected Poems PDF Book It made a lot more sense reading it with the pictures acting it out, because most of the time, I had no idea what Carroll was saying with those crazy made up words. I won a prize and my poem was selected as the best out of all the primary schools in my home town. Added to basket. Hardback edition. The poems range from those written for friends and family, little girls he fancied, Oxford rhymes critiquing his university's politics some things never change , extracts from Wonderland, 'Phantasmagoria', 'The Hunting of the Snark', 'Sylvia and Bruno', and various miscellaneous. The poems are set out chronologically following a generous, thoughtful introduction from the esteemed Cambridge critic Gillian Beer. This edition is the first compiled collection of his poems, including both prominent and lesser known verses. Call us on or send us an email at. Read it Forward Read it first. Shelves: lawsonland , reread , poetry. I didn't really enjoy this collection. Grand Union. More filters. I feel if you can open a book at any page and read a random poem you would enjoy this book more. Hardback All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide There is so much to love an We are building little homes on the sands And time does indeed flit away, burbling and chortling. The humor, sparkling wit and genius of this Victorian Englishman have lasted for more than a century. -

Humpty Dumpty's Explanation

Humpty Dumpty’s Explanation Humpty Dumpty’s explanation of the first verse of Jabberwocky from Through the Looking Glass and Alice’s Adventures there. 'You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,' said Alice. 'Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called "Jabberwocky"?' 'Let's hear it,' said Humpty Dumpty. 'I can explain all the poems that were ever invented--and a good many that haven't been invented just yet.' This sounded very hopeful, so Alice repeated the first verse: 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe. 'That's enough to begin with,' Humpty Dumpty interrupted: 'there are plenty of hard words there. "BRILLIG" means four o'clock in the afternoon--the time when you begin BROILING things for dinner.' 'That'll do very well,' said Alice: and "SLITHY"?' 'Well, "SLITHY" means "lithe and slimy." "Lithe" is the same as "active." You see it's like a portmanteau--there are two meanings packed up into one word.' 'I see it now,' Alice remarked thoughtfully: 'and what are "TOVES"?' 'Well, "TOVES" are something like badgers--they're something like lizards--and they're something like corkscrews.' 'They must be very curious looking creatures.' 'They are that,' said Humpty Dumpty: 'also they make their nests under sun-dials--also they live on cheese.' 'Andy what's the "GYRE" and to "GIMBLE"?' 'To "GYRE" is to go round and round like a gyroscope. To "GIMBLE" is to make holes like a gimlet.' 1 'And "THE WABE" is the grass-plot round a sun-dial, I suppose?' said Alice, surprised at her own ingenuity. -

The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, the Hunting of the Snark, a Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online

yaTOs (Download pdf) The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Online [yaTOs.ebook] The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) Pdf Free Lewis Carroll ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1419651 in Books 2011-11-07Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 1.70 x 6.50 x 9.30l, 1.70 #File Name: 0890097003440 pages | File size: 46.Mb Lewis Carroll : The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Best of Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass, The Hunting of the Snark, A Tangled Tale, Phantasmagoria, Nonsense from Letters): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Wonderful books for a wonderful priceBy llamapyrLewis Carroll must've been the greatest children's book author of his time. I really admire his writing style and the creativity of his books, having grown up on them since I was 6. I've got a bunch of his novels in hardcover and paperback sitting on my shelves, so it seemed only right to add some digital versions to my library :)Anyway, I came here looking for Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and found this set, and for a mere 99 cents it seemed worth a look. -

Spilplus.Journals.Ac.Za

http://spilplus.journals.ac.za http://spilplus.journals.ac.za THE WORLD OF LANGUAGE 2 ITS BEHAVIOURAL BELT by Rudolf P. BOlha SPIL PLUS 25 1994 http://spilplus.journals.ac.za CONTENTS 2 Language behaviour 2.1 General nature: unobservable action 2 2.2 Specific properties 4 2.2.1 Purposiveness 4 2.2.2 Cooperativeness 13 2.2.3 Space-time anchoredness 16 2.2.4 Nonlinguistic embeddedness 18 2.2.5 Innovativeness 21 2.2.6 Stimulus-freedom 22 2.2.7 Appropriateness 24 2.2.8 Rule-governedness 25 2.3 Kinds of language behaviour 26 2.3.1 Forms of language behaviour 27 2.3.1.1 Producing utterances 28 2.3.1.2 Comprehending utterances 30 2.3.1.3 Judging utterances 32 2.3.2 Means of language behaviour 39 2.3.3 Modes of language behaviour 47 2.4 The bounds of language behaviour 51 Notes to Chapter 2 53 Bibliography 62 http://spilplus.journals.ac.za 1 2 Language behaviour In Carrollinian worlds, all sorts of creatures have the remarkable knack of appearing, as it were, from nowhere. For instance, soon after Alice had entered the world created by Gilbert Adair beyond a needle's eye, she witnessed how kittens and puppies, followed by cats and dogs, fell out of the sky: 'Hundreds of cats and dogs .... were pouring down as far as she could see. Once they landed, they would all make a rush for lower ground, gathering there in huddles --- "or puddles, I suppose one ought to say" --- .... ' [TNE 41] In Needle's Eye World, one could accordingly say It rained cats arui dogs, and mean it literally. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

Alice Through the Looking-Glass Is Presented by Special Arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney

This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada’s National Arts Centre in 2014. nov dec 26 19 2015 THEATRE FOR YOUNG AUDIENCES GENEROUSLY SUPPORTED BY STUDY GUIDE Adapted from the Stratford Festival 2014 Study Guide by Luisa Appolloni This production was originally produced at the Stratford Festival in association with Canada's National Arts Centre in 2014. Alice Through the Looking-Glass is presented by special arrangement with the Estate of James Crerar Reaney. 1 THEATRE ETIQUETTE “The theater is so endlessly fascinating because it's so accidental. It's so much like life.” – Arthur Miller Arrive Early: Latecomers may not be admitted to a performance. Please ensure you arrive with enough time to find your seat before the performance starts. Cell Phones and Other Electronic Devices: Please TURN OFF your cell phones/iPods/gaming systems/cameras. We have seen an increase in texting, surfing, and gaming during performances, which is very distracting for the performers and other audience members. The use of cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Talking During the Performance: You can be heard (even when whispering!) by the actors onstage and the audience around you. Disruptive patrons will be removed from the theatre. Please wait to share your thoughts and opinions with others until after the performance. Food/Drinks: Food and hot drinks are not allowed in the theatre. Where there is an intermission, concessions may be open for purchase of snacks and drinks. There is complimentary water in the lobby. Dress: There is no dress code at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, but we respectfully reQuest that patrons refrain from wearing hats in the theatre. -

ARTICLE: Jan Susina: Playing Around in Lewis Carroll's Alice Books

Playing Around in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Books • Jan Susina Mathematician Charles Dodgson’s love of play and his need for rules came together in his use of popular games as part of the structure of the two famous children’s books, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, he wrote under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. The author of this article looks at the interplay between the playing of such games as croquet and cards and the characters and events of the novels and argues that, when reading Carroll (who took a playful approach even in his academic texts), it is helpful to understand games and game play. Charles Dodgson, more widely known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, is perhaps one of the more playful authors of children’s literature. In his career, as a children’s author and as an academic logician and mathematician, and in his personal life, Carroll was obsessed with games and with various forms of play. While some readers are surprised by the seemingly split personality of Charles Dodgson, the serious mathematician, and Lewis Carroll, the imaginative author of children’s books, it was his love of play and games and his need to establish rules and guidelines that effectively govern play that unite these two seemingly disparate facets of Carroll’s personality. Carroll’s two best-known children’s books—Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking- Glass and What Alice Found There (1871)—use popular games as part of their structure. In Victoria through the Looking-Glass, Florence Becker Lennon has gone so far as to suggest about Carroll that “his life was a game, even his logic, his mathematics, and his singular ordering of his household and other affairs. -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, by Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll

www.freeclassicebooks.com Phantasmagoria and Other Poems, By Charles Dodgson, AKA Lewis Carroll www.freeclassicebooks.com 1 www.freeclassicebooks.com Contents PHANTASMAGORIA.................................................................................................................................3 CANTO I‐‐The Trystyng........................................................................................................................3 CANTO II‐‐Hys Fyve Rules....................................................................................................................6 CANTO III‐‐Scarmoges.........................................................................................................................8 CANTO IV‐‐Hys Nouryture.................................................................................................................11 CANTO V‐‐Byckerment......................................................................................................................14 CANTO VI‐‐Dyscomfyture..................................................................................................................17 CANTO VII‐‐Sad Souvenaunce...........................................................................................................20 ECHOES .................................................................................................................................................22 A SEA DIRGE ..........................................................................................................................................23 -

The Hunting of the Snark: an Agony in Eight Fits Free

FREE THE HUNTING OF THE SNARK: AN AGONY IN EIGHT FITS PDF Lewis Carroll | 100 pages | 15 Apr 2011 | The British Library Publishing Division | 9780712358132 | English | London, United Kingdom The hunting of the snark : an agony in eight fits Landseer, H. Last update: This is a mirrored and modified web edition of a file which originally has been published by eBooks Adelaide. You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work, and to make derivative works under the following conditions: you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the licensor; you may not use this work for commercial purposes; if you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license identical to this one. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the licensor. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Please to fancy, if you can, that you are reading a real letter, from a real friend whom you have seen, and whose voice you can seem to yourself to hear wishing you, as I do now with all my heart, a happy Easter. Do you know that delicious dreamy feeling when one first wakes on a summer morning, with the twitter of birds in the air, and the fresh breeze coming in at the open window—when, lying lazily with eyes half shut, one sees as in a dream green boughs waving, or waters rippling in a golden light? It is a pleasure very near to sadness, bringing tears to one's eyes like a beautiful picture or poem.