The Mountains of Wadi Rum 111

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jordan Extension Brochure

Come with Fr. Peter Hopkins, LC & Cris on this amazing adventure! Day 4 – Wadi Rum, Monday July 4 PROPOSED ITINERARY [1] Wadi Rum is one of Jordan's main tourist attractions being the most stunning desert scape in the world, lying 320 km southwest of Amman, 120 km south Day 1 – Mount Nebo, Friday July 1, 2022 We depart bright and early for of Petra and 68 km north of Aqaba on the Red Sea. It's uniquely shaped Jordan, crossing the land border at the Allenby King Hussain Bridge. massive mountains rise out of the pink/red desert sands, which separate one Our first destination will be Mount Nebo, where Moses stood and dark mass from another in a magnificent desert scenery of strange breath- viewed the Promised Land. Since the 3rd century the early Christians made taking beauty, with towering cliffs of weathered stone. After breakfast, we this a site of pilgrimage, building a large basilica by the 6th century. Though will enjoy an unforgettable jeep tour through the desert. With our visit com- little remains of the original buildings, you can still see today the magnificent plete, we begin our journey back to Jerusalem, crossing back into Israel at Byzantine mosaics from that basilica in the newly renovated chapel atop the Allenby King Hussain Bridge border crossing. Overnight in Jerusalem, Mount Nebo. Notre Dame of Jerusalem Center. Farewell Dinner. We continue on to Madaba, (Medba in Scripture) which is an an- Day 5 - Jerusalem, Tuesday July 5 Late night of the 4th or early morning cient town in Jordan, southwest of the capital Amman, situated on the an- hours of the 5th flight are recommended. -

Visitor Management

Twinning JO/12/ENP/OT/20 “Strengthen the institutional tourism system in Jordan by enhancing the capacities of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities in Jordan” Umm ar-Rasas (Kastron Mefa’a). A Basis Towards the Public Use Plan UMM AR-RASAS (KASTRON MEFA’A). A BASIS TOWARDS THE PUBLIC USE PLAN Page 2 UMM AR-RASAS (KASTRON MEFA’A). A BASIS TOWARDS THE PUBLIC USE PLAN The present document has been released on January 2015 within the EC-funded assignment “Strengthen the institutional tourism system in Jordan by enhancing the capacities of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities in Jordan” (ref. no. JO/12/ENO/OT/20). More precisely, it was produced within the activity #2.2, devoted to “Designing a pilot project led by MoTA, DoA and UNESCO focused on a joint and coordinated site management of the cultural heritage of the site Umm ar-Rasas”. Project Leader: Rosanna Binacchi, Italian Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MIBACT), Head of Unit for the Coordination of International Relations Component Coordinator: Gianni Bonazzi, Italian Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MIBACT), Head of the Research and Analysis Department Resident Twinning Advisor: Lara Fantoni, County Government of Florence, Italy, responsible of the Tourist Management Unit Resident Counterpart: Hussein Khirfan, Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Head of Site Management Directorate Short Term Experts appointed for the present document: Carlo Francini, Municipality of Florence, Italy, Site Manager of the "Historic Centre of Florence" -

Travel Brochure

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Antiquities of the AND Red Sea Aegean Sea INCLUDING A TRANSIT OF THE Suez Canal CE E AegeanAthens Sea E R G Mediterranean Sea Sea of Galilee Santorini Jerusalem Jerash Alexandria Amman EGYPT MasadaMasada Dead Sea Alexandria JORDAN ISRAEL Petra Suez Cairo Canal Wadi Rum Giza Aqaba EGYPT Ain Gulf of r Sea of Aqaba e Sokhna Suez v i R UNESCO World e l Heritage Site i Cruise Itinerary N Air Routing Hurghada Land Routing Valley of the Kings Red Sea Valley of the Queens Luxor October 29 to November 11, 2021 Amman u Petra u Luxor u The Pyramids Join us on this custom-designed, 14-day journey to the Suez Canal u Alexandria u Santorini u Athens cradle of civilization. Visit three continents, navigate the 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada legendary Red Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Aegean Sea, 2 Arrive in Athens, Greece/Embark Le Bellot 3 Santorini transit the Suez Canal and experience eight magnificent 4 Cruising the Mediterranean Sea UNESCO World Heritage sites. Cruise for eight nights 5 Alexandria, Egypt aboard the exclusively chartered, Five-Star Le Bellot, 6 Suez Canal transit which features 92 Suites and Staterooms, each with 7 Ain Sokhna for Cairo and Giza (Great Pyramids) a private balcony. Spend one night outside Petra and 8 Hurghada/Disembark ship/Luxor 9 Luxor/Valleys of Kings and Queens/Hurghada/ three nights in Amman. Mid-cruise, overnight in a Reembark ship Nile-view room in Luxor and visit Queen Nefertari’s 10 Aqaba, Jordan/Disembark ship/Wadi Rum/Petra tomb in the Valley of the Queens. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Interpretation and Presentation of Nabataeans Innovative Technologies: Case Study Petra/Jordan

DOCTORAL THESIS Interpretation and Presentation of Nabataeans Innovative Technologies: Case Study Petra/Jordan Submitted to the Faculty of Architecture, Civil Engineering, and Urban Planning Brandenburg University of Technology Cottbus, Germany, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Engineer (Dr. Ing), 2006-2011 by Yazan Safwan Al-Tell (Born 07-04-1977 in Amman, Jordan) Supervisors: Prof. Dr. h.c. Jörg J. Kühn Prof.Dr. Stephen G. Schmid Prof. Dr. Ing. Adolf Hoffmann I Abstract The Nabataeans were people of innovation and technology. Many clear evidences were left behind them that prove this fact. Unfortunately for a site like Petra, visited by crowds of visitors and tourists every day, many major elements need to be strengthened in terms of interpretation and presentation techniques in order to reflect the unique and genuine aspects of the place. The major elements that need to be changed include: un-authorized tour guides, insufficient interpretation site information in terms of quality and display. In spite of Jordan‘s numerous archaeological sites (especially Petra) within the international standards, legislations and conventions that discuss intensively interpretation and presentation guidelines for archaeological site in a country like Jordan, it is not easy to implement these standards in Petra at present for several reasons which include: presence of different stakeholders, lack of funding, local community. Moreover, many interpretation and development plans were previously made for Petra, which makes it harder to determine the starting point. Within the work I did, I proposed two ideas for developing interpretation technique in Petra. First was using the theme technique, which creates a story from the site or from innovations done by the inhabitants, and to be presented to visitors in a modern approach. -

Around the World Classic by Private Jet Sept

Signature Expeditions | 2017 AROUND THE WORLD CLASSIC BY PRIVATE JET SEPT. 27 – OCT. 20 2017 PETRA AND MARRAKECH, WADI RUM, JORDAN ORLANDO MOROCCO TAJ MAHAL, FLORIDA // INDIA Begin and End ANGKOR WAT, CAMBODIA CUSCO AND MACHU SERENGETI PLAIN PICCHU OR NORTH OR NGORONGORO APIA, COAST, PERU CRATER, TANZANIA GREAT BARRIER SAMOA REEF OR DAINTREE, EASTER ISLAND, AUSTRALIA CHILE Signature Expeditions | 2017 AROUND THE WORLD CLASSIC BY PRIVATE JET SEPT. 27 – OCT. 20 2017 // 24 DAYS // 80 GUESTS $79,950 per person, double occupancy $8,950 single supplement OUR CLASSIC JOURNEY OFFERS A LIFE LIST OF ICONIC DESTINATIONS IN A SINGLE ITINERARY. Taj Mahal, India ORLANDO // DAY 1 TAJ MAHAL, INDIA // DAYS 14-15 Meet fellow guests and expedition leaders at a welcome dinner. In the former Mughal capital of Agra, see one of the world’s greatest Ritz-Carlton Orlando, Grande Lakes architectural treasures. Then, tour Emperor Akbar’s grand tomb, visit the rural village of Kachpura or explore Keoladeo National Park and CUSCO AND MACHU PICCHU Bird Sanctuary. Oberoi Amarvilas OR NORTH COAST, PERU // DAYS 2-4 Explore historic Cusco and the Inca ruins of Chinchero before SERENGETI PLAIN OR NGORONGORO CRATER, traveling through the Sacred Valley of the Urubamba to the TANZANIA // DAYS 16-18 mountaintop stronghold of Machu Picchu. Or visit Moche temples Tanzania has more land devoted to game reserves than any other and the adobe city of Chan Chan on Peru’s North Coast. country on earth. From your luxurious safari lodge, search for the Big Belmond Palacio Nazarenas; Hotel Libertador Trujillo Five: lions, leopards, Cape buffalos, elephants and rhinos. -

22 Questions & Answers

22 Questions & Answers March 2018 In the past months various people have raised questions and objections to Dan Gibson’s theory which states that the original city of Mecca was the city of Petra in Jordan. Each question below is a real question that has been asked. Each question follows with Dan Gibson’s response. Some of these questions and objections were made in Arabic and some in Bengali, and have been translated so that everything is in English. 1. OBJECTION: “Beware of major deceptions. This one says Mecca is not the original Mecca, and Gibson does not believe that Muḥammad existed.” Gibson response: While I have researched the history of Mecca, I have never tried to bring doubts that Muḥammad existed. I believe he did exist. The only changes I am suggesting are geographical ones. I hear many objections to my theory, and most of them are about the existence of Muḥammad. Unfortunately these are objections are aimed at other people’s opinions, and are not about my research. I am not like some scholars who doubt the existence of Muḥammad. I believe he was a real person. I hope this is clear to everyone, as I think about half the questions and objections I receive deal with this topic. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 2. OBJECTION: Gibson does not mention many places like Busra and Qiruwan. Kufa is not mentioned. India had the oldest mosque pointing to Mecca. Where are these? GIBSON’S RESPONSE: This question seems to be referring to the list of mosques presented in the film. The film was restricted to 85 minutes, so we had to pick and choose what we would present. -

Religion & Faith Biblical

Ahlan Wa Sahlan Welcome to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, founded by carved from rock over 2000 years ago, it also offers much more King Abdullah I, and currently ruled by King Abdullah II son of for the modern traveller, from the Jordan Valley, fertile and ever the late King Hussein. Over the years, Jordan has grown into a changing, to the remote desert canyons, immense and still. stable, peaceful and modern country. Whether you are a thrill seeker, a historian, or you just want to relax, Jordan is the place for you. While Jordan is known for the ancient Nabataean city of Petra, Content Biblical Jordan 2 Bethany Beyond the Jordan 4 Madaba 6 Mount Nebo 8 Mukawir 10 Tall Mar Elias 11 Anjara 11 Pella 12 As-Salt 12 Umm Qays 13 Umm Ar-Rasas 14 Jerash 15 Petra 16 Umm Ar-Rasas Hisban 17 The Dead Sea & Lot’s Cave 18 Amman 20 Aqaba 21 MAP LEGEND The King’s Highway 22 Historical Site Letters of Acknowledgement 23 Castle Itineraries 24 Religious Site Hotel Accommodation Camping Facilities Showkak Airport Road Highway Railway Bridge Nature / Wildlife Reserve Jordan Tourism Board: Is open Sunday to Thursday (08:00-17:00). Petra, the new world wonder UNESCO, world heritage site 1 BIBLICAL JORDAN The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has proven home to some of the most influential Biblical leaders of the past; Abraham, Job, Moses, Ruth, Elijah, John the Baptist, Jesus Christ and Paul, to name a few. As the only area within the Holy Land visited by all of these great individuals, Jordan breathes with the histories recorded in the Holy Bible. -

History and Culture.Indd

History & Culture Table of Contents Map of Jordan 1 L.Tiberius Umm Qays Welcome 2 Irbid Jaber Amman 4 Pella Hemmeh Ramtha er As-Salt HISTORY & CULTURE12 ITINERARIES Ajlun Mafraq Madaba 14 dan Riv Jerash Deir 'Alla Umm al-Jimal 1 Day Tour Options: Jor Umm Ar-Rasas1. Jerash, Ajlun 16 ey Salt Qasr Al Hallabat Mount Nebo2. Amman (City Tour) 17 all Zarqa Marka 3. Madaba, Mount Nebo, Bethany Beyond the Jordan V dan Jordan Valley & The Dead Sea 18 Jor Amman Iraq al-Amir Qusayr Amra Azraq Karak 20 Bethany Beyond The Jordan Mt. Nebo Qasr Al Mushatta 3 Day Itinerary: Dead Sea Spas Queen Alia Qasr Al Kharrana Petra 22 Madaba International Day 1. Amman, Jerash, Madaba and Dead Sea - Overnight in Ammana Airport e Hammamat Ma’in Aqaba Day 2. Petra - Overnight in26 Little Petra S d Dhiban a Umm Ar-Rasas Jerash Day 3. Karak, Madaba and30 Mount Nebo - Overnight in Ammane D Ajlun 36 5 Day Itinerary: Umm Al-Jimal 38 Qatraneh Day 1. Amman, Jerash, Ajlun - Overnight in Amman Karak Pella 39 Mu'ta Day 2. Madaba, Mount Nebo, Karak - Overnight at PetraAl Mazar aj-Janubi Umm QaysDay 3. Petra - Overnight at40 Petra Shawbak Day 4. Wadi Rum - Overnight42 Dead Sea Tafileh Day 5. Bethany Beyond The Jordan MAP LEGEND Desert Umayyad Castles 44 History & Culture Itineraries 49 Historical Site Shawbak Highway Castle Desert Wadi Musa Petra Religious Site Ma'an Airport Ras an-Naqab Road For further information please contact: Highway Jordan Tourism Board: Tel: +962 6 5678444. It is open daily (08:00- Railway 16:00) except Fridays. -

The Author at Rest on the Trail of T.E. Lawrence in the Wadi Rum

The author at rest on the trail of T.E. Lawrence in the Wadi Rum 40 the philadelphia lawyer fall 2009 The author and wife, Noreen Shanfelter, at The Monastery, the highest point in Petra ack in that lost era when the neighborhood movie the- atre showed a travelogue or newsreel before the main movie attraction, I sat, a teenager, fascinated by a short Bfilm about Petra, the ancient, abandoned “Red City” in the Jor- danian desert. Like Alan Ladd in “High Barbary,” I vowed one day to visit this mysterious sprawl of temples and tombs carved elegantly out of the desert sandstone by a forgotten civilization. Those who saw the aforementioned film will remember that the matinee idol follows his boyhood promise only to find himself at the end floating aimlessly in a lifeboat on an empty ocean expanse at the exact coordinate where revered elders had told him he would find the paradise called “High Barbary.” To the modern traveler/dreamer, Petra is very big and very real – as proven by a recent visit. All photos by Richard G. Freeman the philadelphia lawyer fall 2009 41 We were in Jordan to visit our son Joe who served there in the Peace Corps. We met him in the port city of Aqaba on the Red Sea after crossing very easily from Eilat on the Israeli side. In Aqaba, we witnessed the end of the holy month of Ramadan, an event similar to but on a lower key than New Year’s Eve: cars cruised; horns blared; men shouted. What was different? No women, except Western tourists, were anywhere in sight and no alcohol was visible except inside hotels that served Westerners. -

Around the World a Luxury Tour by Private Jet

AROUND THE WORLD A LUXURY TOUR BY PRIVATE JET October 10 – November 2, 2021 or December 30, 2021 – January 22, 2022 U.S.A. • PERU • CHILE • FIJI • AUSTRALIA • CAMBODIA • INDIA • TANZANIA • JORDAN • MOROCCO TCSWORLDTRAVEL.COM/ATW | 888.664.2218 1 INTRODUCING THE FUTURE Join us for the inaugural OF PRIVATE JET TRAVEL We are excited to announce the newest addition to our fleet, journeys of our luxurious our brand-new private Airbus A321neo-LR. This new, state- of-the-art plane is our next step forward as we continue to new private jet. innovate new ways to explore life- list destinations around the globe. See page 28 for more details. i am so excited to announce our first expedition on our brand new, customized jet. This trip will take you to nine legendary destinations that are as timeless as they are iconic. It is filled with UNESCO World Heritage sites, natural wonders and cultural highlights. The 24-day itinerary is an upgraded version of our most popular expedition, allowing you to do and see even more. Not only will you travel on our new jet, you will also have unique lodging options like a luxury tented camp under the stars in Wadi Rum or a high-end riad in the heart of Marrakech’s medina. This trip also includes Jaipur as an additional destination and more time in the Serengeti. In these unprecedented times, the benefits of traveling by private jet have become even more desirable. Fewer people per plane, a more controlled environment, smaller airports, private or expedited customs and immigration, and the ability to make changes and pivot up to the last minute are all hallmarks of traveling by private jet and are now more important than ever. -

The Leopard in Jordan

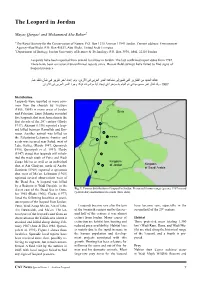

The Leopard in Jordan Mayas Qarqaz1 and Mohammed Abu Baker2 1 The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature. P.O. Box 1215 Amman 11941 Jordan. Current address: Environment Agency-Abu Dhabi. P.O. Box 45553, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 2 Department of Biology, Jordan University of Science & Technology. P.O. Box 3030, Irbid, 22110 Jordan Leopards have been reported from several localities in Jordan. The last confirmed report dates from 1987. There have been occasional unconfirmed reports since. Recent field surveys have failed to find signs of leopard presence. ϡΎѧϋ ϚѧϟΫ ϥ΄ѧη ϲѧϓ ήѧϳήϘΗ ήѧΧ ΩΪϋ· ϢΗϭ ˬϥΩέϷ ϲϓ ϲΑήόϟ ήϤϨϟ ΓΪϫΎθϣ ϰϟ·ήϴθΗ ϲΘϟ ήϳέΎϘΘϟ Ϧϣ ΪϳΪόϟ ϙΎϨϫ .ϥΩέϷ ϲϓ ϲΑήόϟ ήϤϨϟ ΩϮΟϭ ΪϛΆΗ ΕήηΆϣ Δϳ ΩΎΠϳ· ϲϓ ήΧΆϣ ϪΑ ϡΎϴϘϟ ϢΗ ϲϧΪϴϣ δϣ ήΧ Ϟθϓ Ϊϗϭ ˬ1987 Distribution Leopards were reported as more com- mon than the cheetah by Tristram (1866, 1888) in many areas of Jordan Syria and Palestine. Ernst Schmitz recorded five leopards shot near Jerusalem in the first decade of the 20th century (Hardy 1947). Aharoni (1930) reported a leop- ard killed between Ramallah and Em- maus. Another animal was killed on the Palestinian-Lebanese frontier and Amman a cub was secured near Safad, west of Lake Galilee (Hardy 1947, Qumsiyeh 1996, Qumsiyeh et al. 1993). Hardy (1947) stated that leopards still inhab- ited the wadi south of Petra and Wadi Zarqa Ma’en as well as an individual Kingdom shot at Ain Ghidyan, north of Aqaba. of Jordan Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Harrison (1968) reported a specimen shot west of Ma’an. -

Around the World

For more information, please contact Tour Operator,TCS World Travel at 888.502.6067 or visit GoByPrivateJet.com/Ohio-State A LUXURY TOUR BY PRIVATE JET Around the World December 30, 2021 – January 22, 2022 FT. LAUDERDALE MARRAKECH, PETRA AND Begin and End MOROCCO WADI RUM, JORDAN TAJ MAHAL ANGKOR WAT, AND JAIPUR, CAMBODIA INDIA CUSCO AND MACHU SERENGETI PLAIN OR NGORONGORO CRATER, PICCHU or GREAT BARRIER REEF, TANZANIA NADI, FIJI NORTH COAST, PERU AUSTRALIA EASTER ISLAND, CHILE Around the World A LUXURY TOUR BY PRIVATE JET Our flagship journey offers a life list of iconic destinations in a single itinerary. Fly by private jet to explore nine of the world’s most legendary places and natural wonders. DECEMBER 30, 2021 – JANUARY 22, 2022 / 24 DAYS / 48 GUESTS $99,950 per person, double occupancy; $9,995 solo supplement Fort Lauderdale, Florida / December 30 Great Barrier Reef, Australia / January 7 – 8 Petra and Wadi Rum, Jordan / January Meet fellow guests and expedition leaders Cruise to the Great Barrier Reef’s pristine 17 – 18 at a welcome dinner. The Ritz-Carlton, northern reaches to snorkel among a vibrant Discover the Lost City of Petra, which was half Fort Lauderdale collection of coral and tropical fish. Or opt to built and half carved into red sandstone cliffs venture into the Daintree Rainforest, one of by the Nabataeans more than 2,000 years Cusco and Machu Picchu or North Australia’s truly wild areas. Pullman Douglas ago. Explore the starkly beautiful landscapes Coast, Peru / December 31 – January 2 Sea Temple Resort & Spa of Wadi Rum on a 4x4 expedition, or opt to Discover the extraordinary UNESCO World experience the Bedouin way of life with an Heritage site of Machu Picchu and examine Angkor Wat, Cambodia / January 9 – 11 overnight stay at a luxury camp in the desert.