Protecting the Hauraki Gulf Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hauraki Gulf Islands District Plan Review Landscape Report

HAURAKI GULF ISLANDS DISTRICT PLAN REVIEW LANDSCAPE REPORT September 2006 1 Prepared by Hudson Associates Landscape Architects for Auckland City Council as part of the Hauraki Gulf Islands District Plan Review September 2006 Hudson Associates Landscape Architects PO Box 8823 06 877-9808 Havelock North Hawke’s Bay [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Landscape Character 10 Strategic Management Areas 13 Land Units 16 Rakino 31 Rotoroa 33 Ridgelines 35 Outstanding Natural Landscapes 38 Settlement Areas 40 Assessment Criteria 45 Appendix 48 References 51 3 LIST OF FIGURE Figure # Description Page 1. Oneroa 1920’s. photograph 6 2. Oneroa 1950’s photograph 6 3 Great Barrier Island. Medlands Settlement Area 7 4 Colour for Buildings 8 5 Waiheke View Report 9 6 Western Waiheke aerials over 20 years 11 7 Great Barrier Island. Natural landscape 11 8 Karamuramu Island 11 9 Rotoroa Island 12 10 Rakino Island 12 11 Strategic Management Areas 14 12 Planning layers 15 13 Waiheke Land Units 17 14 Great Barrier Island Land Units 18 15 Land Unit 4 Wetlands 19 16 Land Unit 2 Dunes and Sand Flats 19 17 Land Unit 1 Coastal Cliffs and Slopes 20 18 Land Unit 8 Regenerating Slopes 20 19 Growth on Land Unit 8 1988 21 20 Growth on Land Unit 8, 2004 21 21 LU 12 Bush Residential 22 22 Land Unit 20 Onetangi Straight over 18 years 23 23 Kennedy Point 26 24 Cory Road Land Unit 20 27 25 Aerial of Tiri Road 28 26 Land Unit 22 Western Waiheke 29 27 Thompsons Point 30 28 Rakino Island 32 29 Rotoroa Island 34 30 Matiatia, house on ridge 36 31 Ridge east of Erua Rd 36 32 House on secondary ridge above Gordons Rd 37 4 INTRODUCTION 5 INTRODUCTION This report has been prepared to document some of the landscape contribution made in the preparation of the Hauraki Gulf Islands District Plan Review 2006. -

Kupe Press Release

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Image Credit: Pä-kanae (fish trap), Hokianga, Northland. Photograph by Michael Hall Kupe Sites Ngä tapuwae o Kupe Landmarks of the great voyager An exhibition developed by Te Papa that Wairarapa, the Wellington region, and the top of celebrates a great Polynesian voyager’s the South Island. connections with New Zealand opens at Whangarei Art Museum on 11th June. Kupe is The exhibition has its origin in research regarded by many iwi (tribes) as the ancestor who undertaken for the exhibition Voyagers: discovered this country. Kupe Sites, a touring Discovering the Pacific at Te Papa in 2002. Kupe exhibition from the Museum of New Zealand Te was one of four notable Pacific voyagers whose Papa Tongarewa, explores the stories of Kupe’s achievements were celebrated in that exhibition. encounter with New Zealand through names of Te Papa researchers, along with photographer various landmarks and places and even the name Michael Hall, visited the four areas and worked Aotearoa. with iwi there to capture this powerful images. Some iwi tell the story of Kupe setting out from Kupe Sites offers visitors a unique encounter with his homeland Hawaiki in pursuit of Te Wheke-a- New Zealand’s past and reveals the significance of Muturangi, a giant octopus. Others recount how landscape and memory in portraying a key figure Kupe, in love with his nephew’s wife, took her in the country’s history. husband fishing, left him out at sea to drown, then fled from the family’s vengeance. The exhibition runs until 27th August, 2018. -

Coastal Resources Limited Marine Dumping Consent Application

Coastal Resources Limited marine dumping consent application Submission Reference no: 78 Izzy Fordham (alternatively Helgard Wagener), Aotea Great Barrier Local Board Submitter Type: Not specified Source: Email Overall Notes: Clause Do you intend to have a spokesperson who will act on your behalf (e.g. a lawyer or professional adviser)? Position Yes Notes The chair of the Aotea Great Barrier Local Board Clause Please list your spokesperson's first name and last name, email address, phone number, and postal address. Notes Izzy Fordham, [email protected], 0212867555, Aotea Great Barrier Local Board, 81 Hector Sanderson Road, Claris, Great Barrier Island Clause Do you wish to speak to your submission at the hearing? Position Yes I/we wish to speak to my/our submission at the hearing Notes Clause If you wish to speak to your submission at the hearing, tick the boxes that apply to you: Position If others make a similar submission I/we will consider presenting a joint case with them at the hearing. Notes Clause We will send you regular updates by email Position I can receive emails and my email address is correct. Notes Clause What decision do you want the EPA to make and why? Provide reasons in the box below. Position Refuse Notes Full submission is attached Coastal Resources Ltd Marine Dumping Consent: Submission by the Aotea Great Barrier Local Board Proposal number: EEZ100015 Executive Summary 1. The submission is made by the Aotea Great Barrier Local Board on behalf of our community, who object to the application. Our island is the closest community to the proposed dump site and the most likely to be affected. -

Towards an Economic Valuation of the Hauraki Gulf: a Stock-Take of Activities and Opportunities

Towards an Economic Valuation of the Hauraki Gulf: A Stock-take of Activities and Opportunities November 2012 Technical Report: 2012/035 Auckland Council Technical Report TR2012/035 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-1-927216-15-6 (Print) ISBN 978-1-927216-16-3 (PDF) Recommended citation: Barbera, M. 2012. Towards an economic valuation of the Hauraki Gulf: a stock-take of activities and opportunities. Auckland Council technical report TR2012/035 © 2012 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council’s copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. Auckland Council does not give any warranty whatsoever, including without limitation, as to the availability, accuracy, completeness, currency or reliability of the information or data (including third party data) made available via the publication and expressly disclaim (to the maximum extent permitted in law) all liability for any damage or loss resulting from your use of, or reliance on the publication or the information and data provided via the publication. The publication, information, and data contained within it are provided on an "as is" basis. -

Historic Heritage Survey Aotea Great Barrier Island

Historic Heritage Survey Aotea Great Barrier Island May 2019 Prepared by Megan Walker and Robert Brassey © 2019 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council’s copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. Auckland Council does not give any warranty whatsoever, including without limitation, as to the availability, accuracy, completeness, currency or reliability of the information or data (including third party data) made available via the publication and expressly disclaim (to the maximum extent permitted in law) all liability for any damage or loss resulting from your use of, or reliance on the publication or the information and data provided via the publication. The publication, information, and data contained within it are provided on an "as is" basis. All contemporary images have been created by Auckland Council except where otherwise attributed. Cover image: Ox Park (Auckland Council 2016) Aotea Great Barrier Island Heritage Survey Draft Report 2 Executive Summary Aotea – Great Barrier has had a long and eventful Māori and European history. In the more recent past there has been a slow rate of development due to the island’s relative isolation. -

And Did She Cry in Māori?”

“ ... AND DID SHE CRY IN MĀORI?” RECOVERING, REASSEMBLING AND RESTORYING TAINUI ANCESTRESSES IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Diane Gordon-Burns Tainui Waka—Waikato Iwi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Canterbury 2014 Preface Waikato taniwha rau, he piko he taniwha he piko he taniwha Waikato River, the ancestral river of Waikato iwi, imbued with its own mauri and life force through its sheer length and breadth, signifies the strength and power of Tainui people. The above proverb establishes the rights and authority of Tainui iwi to its history and future. Translated as “Waikato of a hundred chiefs, at every bend a chief, at every bend a chief”, it tells of the magnitude of the significant peoples on every bend of its great banks.1 Many of those peoples include Tainui women whose stories of leadership, strength, status and connection with the Waikato River have been diminished or written out of the histories that we currently hold of Tainui. Instead, Tainui men have often been valorised and their roles inflated at the expense of Tainui women, who have been politically, socially, sexually, and economically downplayed. In this study therefore I honour the traditional oral knowledges of a small selection of our tīpuna whaea. I make connections with Tainui born women and those women who married into Tainui. The recognition of traditional oral knowledges is important because without those histories, remembrances and reconnections of our pasts, the strengths and identities which are Tainui women will be lost. Stereotypical male narrative has enforced a female passivity where women’s strengths and importance have become lesser known. -

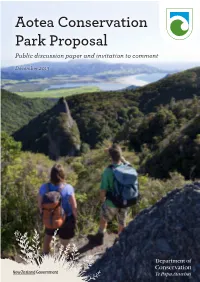

Aotea Conservation Park Proposal Public Discussion Paper and Invitation to Comment

Aotea Conservation Park Proposal Public discussion paper and invitation to comment December 2013 Cover: Trampers taking in the view of Whangapoua beach and estuary from Windy Canyon Track, Aotea/Great Barrier Island. Photo: Andris Apse © Copyright 2013, New Zealand Department of Conservation In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 4 2. PROPOSED AOTEA CONSERVATION PARK ................................................................................ 5 2.1 Why is the Department proposing a conservation park? .................................................... 5 2.2 What is a conservation park? ................................................................................................................ 5 2.3 What are the benefits of creating a conservation park? ....................................................... 6 2.4 Proposed boundaries .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.4.1 Map 1: Proposed Aotea Conservation Park ....................................................................... 7 2.4.2 Map 2: Proposed Aotea Conservation Park and other conservation land on Aotea/Great Barrier Island ...................................................................................... 8 2.4.3 Table 1: Land proposed for inclusion in -

New Zealand Local Pages

NEW ZEALAND LOCAL PAGES AREA PRESIDENCY MESSAGE The Prophetic Promise of the Messiah By Elder Kevin W. Pearson First Counsellor in the Area Presidency he birth of Jesus Christ in the proclamation of the truth, in Tmeridian of time was one great power and authority, there of the most anticipated events were but few who hearkened in all recorded ancient scrip- to his voice, and rejoiced in his ture. Beginning with Adam and presence, and received salva- continuing with every ancient tion at his hands” (D&C 138:26). prophet through the ages, the Contrast that with “the angel promise of the Messiah, the [and] a multitude of the heavenly Redeemer, the Saviour, and the host praising God, and saying, Only Begotten Son of God was Glory to God in the highest, and Elder Kevin W. foretold. on earth peace, good will toward Pearson The righteous have wor- men” (Luke 2:13–14). their deliverance was at hand. shiped the Father in the name The birth of the Son of God They were assembled awaiting of the Son and have exercised would have been one of the the advent of the Son of God into faith in Him, repented and most acknowledged and cele- the spirit world, to declare their covenanted through baptism brated days in all of recorded redemption from the bands of and received the gift of the Holy history in the pre-mortal realm. death” (D&C 138:12,15–16). Ghost in every age where the His mission there would be the He will come again, and all His Melchizedek Priesthood has very foundation of the Father’s words will be fulfilled which He been available on the earth. -

Great Barrier Island Aotea Brochure

AUCKLAND Further information Great Barrier Aotea / Great Barrier Island Base Private Bag 96002 Island/Aotea Great Barrier Island 0961 Hauraki Gulf Marine Park PHONE: 09 429 0044 EMAIL: [email protected] www.doc.govt.nz Published by: Department of Conservation DOC Aotea / Great Barrier Island Base Private Bag 96002 Great Barrier Island October 2019 Editing and design: DOC Creative Services, Conservation House, Wellington Front cover: Aotea Track. Photo: Andris Apse Back cover: Kākā landing in a pōhutukawa tree. Photo: Leon Berard This publication is produced using paper sourced from well-managed, renewable and legally logged forests. R153740 Contents Aotea and Ngāti Rehua Aotea and Ngāti Rehua .................1 The island renown Ridge to reef ..........................2 The west coast ...........................3 Aotea is the ancestral land of the The east coast ............................3 Ngāti Rehua hapū of Ngāti Wai. It is Marine life ................................4 the southeastern outpost of the tribal rohe of the Ngāti Wai iwi. Seabirds ..................................4 Rich history ..........................5 Although each island, islet and rock has its own individual character and identity, Aotea is Mining ...................................5 viewed as a single physical and spiritual entity Whaling ..................................6 over which a ‘spiritual grid’ lies. At its centre Shipwrecks ...............................6 stands Hirakimata (Mt Hobson), the maunga Historic buildings. 6 tapu of Ngāti Rehua. To the -

SHOREBIRDS of the HAURAKI GULF Around the Shores of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park

This poster celebrates the species of birds commonly encountered SHOREBIRDS OF THE HAURAKI GULF around the shores of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park. Red knot Calidris canutus Huahou Eastern curlew Numenius madagascariensis 24cm, 120g | Arctic migrant 63cm, 900g | Arctic migrant South Island pied oystercatcher Haematopus finschi Torea Black stilt 46cm, 550g | Endemic Himantopus novaezelandiae Kaki 40cm, 220g | Endemic Pied stilt Himantopus himantopus leucocephalus Poaka 35cm, 190g | Native (breeding) (non-breeding) Variable oystercatcher Haematopus unicolor Toreapango 48cm, 725g | Endemic Bar-tailed godwit Limosa lapponica baueri Kuaka male: 39cm, 300g | female: 41cm, 350g | Arctic migrant Spur-winged plover Vanellus miles novaehollandiae 38cm, 360g | Native Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus variegatus Wrybill Anarhynchus frontalis 43cm, 450g | Arctic migrant Ngutu pare Ruddy turnstone 20cm, 60g | Endemic Arenaria interpres Northern New Zealand dotterel Charadrius obscurus aquilonius Tuturiwhatu 23cm, 120g | Arctic migrant Shore plover 25cm, 160g | Endemic Thinornis novaeseelandiae Tuturuatu Banded dotterel Charadrius bicinctus bicinctus Pohowera 20cm, 60g | Endemic 20cm, 60g | Endemic (male breeding) Pacific golden plover Pluvialis fulva (juvenile) 25cm, 130g | Arctic migrant (female non-breeding) (breeding) Black-fronted dotterel Curlew sandpiper Calidris ferruginea Elseyornis melanops 19cm, 60g | Arctic migrant 17cm, 33g | Native (male-breeding) (non-breeding) (breeding) (non-breeding) Terek sandpiper Tringa cinerea 23cm, 70g | Arctic migrant -

Elegant Report

C U L T U R A L IMPACT R E P O R T Wellington Airport Limited – South Runway extension Rongotai – Hue te Taka IN ASSOCIATION WITH PORT NICHOLSON BLOCK SETTLEMENT TRUST, WELLINGTON TENTHS TRUST AND TE ATIAWA KI TE UPOKO O TE IKA A MAUI POTIKI TRUST (MIO) OCTOBER 2015 CULTURAL IMPACT REPORT Wellington Airport – South Runway extension RONGOTAI – HUE TE TAKA TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................................3 THE PROJECT .............................................................................................................................................4 KEY MAORI VALUES ASSOCIATED WITH THIS AREA ..................................................................6 FISHING AND FISHERIES IN THE AREA ...........................................................................................................8 MARINE FLORA .......................................................................................................................................... 10 BLACK-BACKED GULLS ............................................................................................................................. 10 WATER QUALITY........................................................................................................................................ 11 Consultation .......................................................................................................................................... 12 RECREATION USE OF THE -

Auckland Region

© Lonely Planet Publications 96 lonelyplanet.com 97 AUCKLAND REGION Auckland Region AUCKLAND REGION Paris may be the city of love, but Auckland is the city of many lovers, according to its Maori name, Tamaki Makaurau. In fact, her lovers so desired this beautiful place that they fought over her for centuries. It’s hard to imagine a more geographically blessed city. Its two magnificent harbours frame a narrow isthmus punctuated by volcanic cones and surrounded by fertile farmland. From any of its numerous vantage points you’ll be astounded at how close the Tasman Sea and Pacific Ocean come to kissing and forming a new island. As a result, water’s never far away – whether it’s the ruggedly beautiful west-coast surf beaches or the glistening Hauraki Gulf with its myriad islands. The 135,000 pleasure crafts filling Auckland’s marinas have lent the city its most durable nickname: the ‘City of Sails’. Within an hour’s drive from the high-rise heart of the city are dense tracts of rainforest, thermal springs, deserted beaches, wineries and wildlife reserves. Yet big-city comforts have spread to all corners of the Auckland Region: a decent coffee or chardonnay is usually close at hand. Yet the rest of the country loves to hate it, tut-tutting about its traffic snarls and the supposed self-obsession of the quarter of the country’s population that call it home. With its many riches, Auckland can justifiably respond to its detractors, ‘Don’t hate me because I’m beautiful’. HIGHLIGHTS Going with the flows, exploring Auckland’s fascinating volcanic