Switching Techniques in Data Acquisition Systems for Future Experiments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Switching Techniques Frequency Division Multiplexing

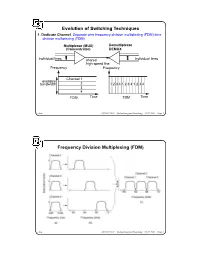

Evolution of Switching Techniques 1. Dedicate Channel. Separate wire frequency division multiplexing (FDM) time division multiplexing (TDM) Multiplexor (MUX) Demultiplexor (Concentrator) DEMUX individual lines shared individual lines high speed line Frequency Frequency Channel 1 available bandwidth 2 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 3 4 FDM Time TDM Time chow CS522 F2001—Multiplexing and Switching—10/17/2001—Page 1 Frequency Division Multiplexing (FDM) chow CS522 F2001—Multiplexing and Switching—10/17/2001—Page 2 Wavelength Division Multiplexing chow CS522 F2001—Multiplexing and Switching—10/17/2001—Page 3 Impact of WDM z Many big organizations are starting projects to design WDM system or DWDN (Dense Wave Division Mutiplexing Network). We may see products appear in next three years.In Fujitsu and CCL/Taiwan, 128 different wavelengthes on the same strand of fiber was reported working in the lab. z We may have optical routers between end systems that can take one wavelenght signal, covert to different wavelenght, send it out on different links. Some are designing traditional routers that covert optical signal to electronical signal, and use time slot interchange based on high speed memory to do the switching, the convert the electronic signal back to optical signal. z With this type of optical networks, we will have a virtual circuit network, where each connection is assigned some wave length. Each connection can have 2.4 gbps tremedous bandwidth. z With inital 128 different wavelength, we can have about 10 end users. If each pair of end users needs to communicate simultaneously, it will use 10*10=100 different wavelength. -

Physical Layer Overview

ELEC3030 (EL336) Computer Networks S Chen Physical Layer Overview • Physical layer forms the basis of all networks, and we will first revisit some of fundamental limits imposed on communication media by nature Recall a medium or physical channel has finite Spectrum bandwidth and is noisy, and this imposes a limit Channel bandwidth: on information rate over the channel → This H Hz is a fundamental consideration when designing f network speed or data rate 0 H Type of medium determines network technology → compare wireless network with optic network • Transmission media can be guided or unguided, and we will have a brief review of a variety of transmission media • Communication networks can be classified as switched and broadcast networks, and we will discuss a few examples • The term “physical layer protocol” as such is not used, but we will attempt to draw some common design considerations and exams a few “physical layer standards” 13 ELEC3030 (EL336) Computer Networks S Chen Rate Limit • A medium or channel is defined by its bandwidth H (Hz) and noise level which is specified by the signal-to-noise ratio S/N (dB) • Capability of a medium is determined by a physical quantity called channel capacity, defined as C = H log2(1 + S/N) bps • Network speed is usually given as data or information rate in bps, and every one wants a higher speed network: for example, with a 10 Mbps network, you may ask yourself why not 10 Gbps? • Given data rate fd (bps), the actual transmission or baud rate fb (Hz) over the medium is often different to fd • This is for -

Lecture 8: Overview of Computer Networking Roadmap

Lecture 8: Overview of Computer Networking Slides adapted from those of Computer Networking: A Top Down Approach, 5th edition. Jim Kurose, Keith Ross, Addison-Wesley, April 2009. Roadmap ! what’s the Internet? ! network edge: hosts, access net ! network core: packet/circuit switching, Internet structure ! performance: loss, delay, throughput ! media distribution: UDP, TCP/IP 1 What’s the Internet: “nuts and bolts” view PC ! millions of connected Mobile network computing devices: server Global ISP hosts = end systems wireless laptop " running network apps cellular handheld Home network ! communication links Regional ISP " fiber, copper, radio, satellite access " points transmission rate = bandwidth Institutional network wired links ! routers: forward packets (chunks of router data) What’s the Internet: “nuts and bolts” view ! protocols control sending, receiving Mobile network of msgs Global ISP " e.g., TCP, IP, HTTP, Skype, Ethernet ! Internet: “network of networks” Home network " loosely hierarchical Regional ISP " public Internet versus private intranet Institutional network ! Internet standards " RFC: Request for comments " IETF: Internet Engineering Task Force 2 A closer look at network structure: ! network edge: applications and hosts ! access networks, physical media: wired, wireless communication links ! network core: " interconnected routers " network of networks The network edge: ! end systems (hosts): " run application programs " e.g. Web, email " at “edge of network” peer-peer ! client/server model " client host requests, receives -

Circuit-Switched Coherence

Circuit-Switched Coherence ‡Natalie Enright Jerger, ‡Mikko Lipasti, and ?Li-Shiuan Peh ‡Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison ?Department of Electrical Engineering, Princeton University Abstract—Circuit-switched networks can significantly lower contention, overall system performance can degrade by 20% the communication latency between processor cores, when or more. This latency sensitivity coupled with low link uti- compared to packet-switched networks, since once circuits are set up, communication latency approaches pure intercon- lization motivates our exploration of circuit-switched fabrics nect delay. However, if circuits are not frequently reused, the for CMPs. long set up time and poorer interconnect utilization can hurt Our investigations show that traditional circuit-switched overall performance. To combat this problem, we propose a hybrid router design which intermingles packet-switched networks do not perform well, as circuits are not reused suf- flits with circuit-switched flits. Additionally, we co-design a ficiently to amortize circuit setup delay. This observation prediction-based coherence protocol that leverages the exis- motivates a network with a hybrid router design that sup- tence of circuits to optimize pair-wise sharing between cores. The protocol allows pair-wise sharers to communicate di- ports both circuit and packet switching with very fast circuit rectly with each other via circuits and drives up circuit reuse. reconfiguration (setup/teardown). Our preliminary results Circuit-switched coherence provides overall system perfor- show this leading to up to 8% improvement in overall system mance improvements of up to 17% with an average improve- performance over a packet-switched fabric. ment of 10% and reduces network latency by up to 30%. -

Medium Access Control Layer

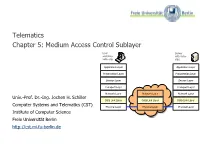

Telematics Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer User Server watching with video Beispielbildvideo clip clips Application Layer Application Layer Presentation Layer Presentation Layer Session Layer Session Layer Transport Layer Transport Layer Network Layer Network Layer Network Layer Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller Data Link Layer Data Link Layer Data Link Layer Computer Systems and Telematics (CST) Physical Layer Physical Layer Physical Layer Institute of Computer Science Freie Universität Berlin http://cst.mi.fu-berlin.de Contents ● Design Issues ● Metropolitan Area Networks ● Network Topologies (MAN) ● The Channel Allocation Problem ● Wide Area Networks (WAN) ● Multiple Access Protocols ● Frame Relay (historical) ● Ethernet ● ATM ● IEEE 802.2 – Logical Link Control ● SDH ● Token Bus (historical) ● Network Infrastructure ● Token Ring (historical) ● Virtual LANs ● Fiber Distributed Data Interface ● Structured Cabling Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.2 Design Issues Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.3 Design Issues ● Two kinds of connections in networks ● Point-to-point connections OSI Reference Model ● Broadcast (Multi-access channel, Application Layer Random access channel) Presentation Layer ● In a network with broadcast Session Layer connections ● Who gets the channel? Transport Layer Network Layer ● Protocols used to determine who gets next access to the channel Data Link Layer ● Medium Access Control (MAC) sublayer Physical Layer Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Jochen H. Schiller ▪ cst.mi.fu-berlin.de ▪ Telematics ▪ Chapter 5: Medium Access Control Sublayer 5.4 Network Types for the Local Range ● LLC layer: uniform interface and same frame format to upper layers ● MAC layer: defines medium access .. -

F. Circuit Switching

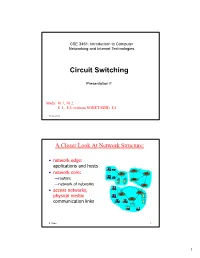

CSE 3461: Introduction to Computer Networking and Internet Technologies Circuit Switching Presentation F Study: 10.1, 10.2, 8 .1, 8.2 (without SONET/SDH), 8.4 10-02-2012 A Closer Look At Network Structure: • network edge: applications and hosts • network core: —routers —network of networks • access networks, physical media: communication links d. xuan 2 1 The Network Core • mesh of interconnected routers • the fundamental question: how is data transferred through net? —circuit switching: dedicated circuit per call: telephone net —packet-switching: data sent thru net in discrete “chunks” d. xuan 3 Network Layer Functions • transport packet from sending to receiving hosts application transport • network layer protocols in network data link network physical every host, router network data link network data link physical data link three important functions: physical physical network data link • path determination: route physical network data link taken by packets from source physical to dest. Routing algorithms network network data link • switching: move packets from data link physical physical router’s input to appropriate network data link application router output physical transport network data link • call setup: some network physical architectures require router call setup along path before data flows d. xuan 4 2 Network Core: Circuit Switching End-end resources reserved for “call” • link bandwidth, switch capacity • dedicated resources: no sharing • circuit-like (guaranteed) performance • call setup required d. xuan 5 Circuit Switching • Dedicated communication path between two stations • Three phases — Establish (set up connection) — Data Transfer — Disconnect • Must have switching capacity and channel capacity to establish connection • Must have intelligence to work out routing • Inefficient — Channel capacity dedicated for duration of connection — If no data, capacity wasted • Set up (connection) takes time • Once connected, transfer is transparent • Developed for voice traffic (phone) g. -

Application Note: 2-Cell Test Environment

Application Note 2-cell Test Environment MD8475A Signalling Tester 1. Background to LTE Rollout Mobile phones appearing in the late 1980s soon experienced rapid evolution of functions from 1990 to 2000 and also spread worldwide as key communications infrastructure. The mobile phone is not limited to just two-way communications between two people but also supports sending and receiving of Short Message Services (SMS), web browsing using the Internet, application and video download, etc., and has become a popular and key cultural tool supporting a fuller lifestyle for many people. Figure 1. Evolution on UE According to one research company, total mobile phone (terminal) shipments at the end of 2010 were valued at $38 billion split between 45% for 2G phones and 49% for 3G. Table 1. Mobile Terminal Shipments Mobile Terminal Shipments ($38 billion total) LTE 1.3% WiMAX 4.0% W-CDMA 40.0% CDMA 9.3% GSM 45.4% 1 MD8475A-E-F-1 The purpose of the shift from 2G to 3G systems was to make more efficient use of frequency bandwidths and was closely related to the explosive growth of the Internet. While still maintaining the easy portability of a mobile phone, users were able to access the information they needed easily at any time and place using the Internet. Similarly to growth of 3G technology, the requirements of LTE systems, which is are positioned in the market as 3.9G to maintain competitiveness with coming 4G systems, are being examined. Connectivity with IP-based core networks must be maintained to support multimedia applications and ubiquitous networks using the packet domain. -

6.02 Notes, Chapter 15: Sharing a Channel: Media Access (MAC

MIT 6.02 DRAFT Lecture Notes Last update: November 3, 2012 CHAPTER 15 Sharing a Channel: Media Access (MAC) Protocols There are many communication channels, including radio and acoustic channels, and certain kinds of wired links (coaxial cables), where multiple nodes can all be connected and hear each other’s transmissions (either perfectly or with some non-zero probability). This chapter addresses the fundamental question of how such a common communication channel—also called a shared medium—can be shared between the different nodes. There are two fundamental ways of sharing such channels (or media): time sharing and frequency sharing.1 The idea in time sharing is to have the nodes coordinate with each other to divide up the access to the medium one at a time, in some fashion. The idea in frequency sharing is to divide up the frequency range available between the different transmitting nodes in a way that there is little or no interference between concurrently transmitting nodes. The methods used here are the same as in frequency division multiplexing, which we described in the previous chapter. This chapter focuses on time sharing. We will investigate two common ways: time division multiple access,orTDMA , and contention protocols. Both approaches are used in networks today. These schemes for time and frequency sharing are usually implemented as communica tion protocols. The term protocol refers to the rules that govern what each node is allowed to do and how it should operate. Protocols capture the “rules of engagement” that nodes must follow, so that they can collectively obtain good performance. -

Research on Super 3G Technology

03-10E_T-Box_3.3 06.12.26 10:07 AM ページ 55 NTT DoCoMo Technical Journal Vol. 8 No.3 Part 2: Research on Super 3G Technology In this part 2 of the Super 3G research that is being conducted to achieve a smooth transition from 3G to 4G, we present technology that is currently being studied for standardization as technical details. Sadayuki Abeta, Minami Ishii, Yasuhiro Kato and Kenichi Higuchi At the RAN WG1 meeting of November 2005, there was 1. Introduction agreement by many companies that high commonality is As explained in part1, Super 3G, the so-called Evolved extremely important and wireless access should be the same for URAN and UTRAN or Long term evolution by the 3rd FDD (paired spectrum) and TDD (unpaired spectrum). As this Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) has been extensively common wireless access system for FDD and TDD, Orthogonal studied since 2005. Agreement on the requirement was reached Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA), which features in June of 2005 to begin investigation of specific technologies. highly efficient frequency utilization was approved for the In June 2006, it was agreed that investigation of the feasibility downlink and Single-Carrier Frequency Division Multiple of the basic approach for satisfying the requirements was essen- Access (SC-FDMA) was approved for the uplink at the tially completed, and effort shifted to the work item phase to December 2005 Plenary Meeting. start the detailed specifications work. Here, we explain technol- The features of the wireless access system are described in ogy that has been proposed as study items. -

UMTS Core Network

UMTS Core Network V. Mancuso, I. Tinnirello GSM/GPRS Network Architecture Radio access network GSM/GPRS core network BSS PSTN, ISDN PSTN, MSC GMSC BTS VLR MS BSC HLR PCU AuC SGSN EIR BTS IP Backbone GGSN database Internet V. Mancuso, I. Tinnirello 3GPP Rel.’99 Network Architecture Radio access network Core network (GSM/GPRS-based) UTRAN PSTN Iub RNC MSC GMSC Iu CS BS VLR UE HLR Uu Iur AuC Iub RNC SGSN Iu PS EIR BS Gn IP Backbone GGSN database Internet V. Mancuso, I. Tinnirello 3GPP RelRel.’99.’99 Network Architecture Radio access network 2G => 3G MS => UE UTRAN (User Equipment), often also called (user) terminal Iub RNC New air (radio) interface BS based on WCDMA access UE technology Uu Iur New RAN architecture Iub RNC (Iur interface is available for BS soft handover, BSC => RNC) V. Mancuso, I. Tinnirello 3GPP Rel.’99 Network Architecture Changes in the core Core network (GSM/GPRS-based) network: PSTN MSC is upgraded to 3G MSC GMSC Iu CS MSC VLR SGSN is upgraded to 3G HLR SGSN AuC SGSN GMSC and GGSN remain Iu PS EIR the same Gn GGSN AuC is upgraded (more IP Backbone security features in 3G) Internet V. Mancuso, I. Tinnirello 3GPP Rel.4 Network Architecture UTRAN Circuit Switched (CS) core network (UMTS Terrestrial Radio Access Network) MSC GMSC Server Server SGW SGW PSTN MGW MGW New option in Rel.4: GERAN (GSM and EDGE Radio Access Network) PS core as in Rel.’99 V. Mancuso, I. Tinnirello 3GPP Rel.4 Network Architecture MSC Server takes care Circuit Switched (CS) core of call control signalling network The user connections MSC GMSC are set up via MGW Server Server (Media GateWay) SGW SGW PSTN “Lower layer” protocol conversion in SGW MGW MGW (Signalling GateWay) RANAP / ISUP PS core as in Rel.’99 SS7 MTP IP Sigtran V. -

Circuit Switching in the Internet

CIRCUIT SWITCHING IN THE INTERNET A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Pablo Molinero Fernandez June 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3090644 Copyright 2003 by Molinero Fernandez, Pablo All rights reserved. ® UMI UMI Microform 3090644 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © Copyright by Pablo Molinero Fernandez 2003 All Rights Reserved ii Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree ofD/pctor of Philosophy. Nick McKeown (Principal Adviser) I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________ Balaji Prabhakar I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. NfSibTas Bambos Approved for the University Committee on Graduate Studies: iii Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Multiple Access Techniques for 4G Mobile Wireless Networks Dr Rupesh Singh, Associate Professor & HOD ECE, HMRITM, New Delhi

International Journal of Engineering Research and Development e-ISSN: 2278-067X, p-ISSN: 2278-800X, www.ijerd.com Volume 5, Issue 11 (February 2013), PP. 86-94 Multiple Access Techniques For 4G Mobile Wireless Networks Dr Rupesh Singh, Associate Professor & HOD ECE, HMRITM, New Delhi Abstract:- A number of new technologies are being integrated by the telecommunications industry as it prepares for the next generation mobile services. One of the key changes incorporated in the multiple channel access techniques is the choice of Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) for the air interface. This paper presents a survey of various multiple channel access schemes for 4G networks and explains the importance of these schemes for the improvement of spectral efficiencies of digital radio links. The paper also discusses about the use of Multiple Input/Multiple Output (MIMO) techniques to improve signal reception and to combat the effects of multipath fading. A comparative performance analysis of different multiple access schemes such as Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA), FDMA, Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) & Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) is made vis-à-vis design parameters to highlight the advantages and limitations of these schemes. Finally simulation results of implementing some access schemes in MATLAB are provided. I. INTRODUCTION 4G (also known as Beyond 3G), an abbreviation of Fourth-Generation, is used for describing the next complete evolution in wireless communications. A 4G system will be a complete replacement for current networks and will be able to provide a comprehensive and secure IP solution. Here, voice, data, and streamed multimedia can be given to users on an "Anytime, Anywhere" basis, and at much higher data rates than the previous generations [1], [2], [3].