Airline On-Time Performance and Its Effects on Consumer Choice Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United-2016-2021.Pdf

27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.pdf 1 4/5/17 7:41 AM 2016 – 2021 Flight Attendant Agreement Association of Flight Attendants – CWA 27010_Contract_JCBA-FA_v10-cover.indd170326_L01_CRV.indd 1 1 3/31/174/5/17 7:533:59 AMPM TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 Recognition, Successorship and Mergers . 1 Section 2 Definitions . 4 Section 3 General . 10 Section 4 Compensation . 28 Section 5 Expenses, Transportation and Lodging . 36 Section 6 Minimum Pay and Credit, Hours of Service, and Contractual Legalities . 42 Section 7 Scheduling . 56 Section 8 Reserve Scheduling Procedures . 88 Section 9 Special Qualification Flight Attendants . 107 Section 10 AMC Operation . .116 Section 11 Training & General Meetings . 120 Section 12 Vacations . 125 Section 13 Sick Leave . 136 Section 14 Seniority . 143 Section 15 Leaves of Absence . 146 Section 16 Job Share and Partnership Flying Programs . 158 Section 17 Filling of Vacancies . 164 Section 18 Reduction in Personnel . .171 Section 19 Safety, Health and Security . .176 Section 20 Medical Examinations . 180 Section 21 Alcohol and Drug Testing . 183 Section 22 Personnel Files . 190 Section 23 Investigations & Grievances . 193 Section 24 System Board of Adjustment . 206 Section 25 Uniforms . 211 Section 26 Moving Expenses . 215 Section 27 Missing, Interned, Hostage or Prisoner of War . 217 Section 28 Commuter Program . 219 Section 29 Benefits . 223 Section 30 Union Activities . 265 Section 31 Union Security and Check-Off . 273 Section 32 Duration . 278 i LETTERS OF AGREEMENT LOA 1 20 Year Passes . 280 LOA 2 767 Crew Rest . 283 LOA 3 787 – 777 Aircraft Exchange . 285 LOA 4 AFA PAC Letter . 287 LOA 5 AFA Staff Travel . -

Volume I Restoration of Historic Streetcar Service

VOLUME I ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT RESTORATION OF HISTORIC STREETCAR SERVICE IN DOWNTOWN LOS ANGELES J U LY 2 0 1 8 City of Los Angeles Department of Public Works, Bureau of Engineering Table of Contents Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. ES-1 ES.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... ES-1 ES.2 Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................................................... ES-1 ES.3 Background ............................................................................................................................................................ ES-2 ES.4 7th Street Alignment Alternative ................................................................................................................... ES-3 ES.5 Safety ........................................................................................................................................................................ ES-7 ES.6 Construction .......................................................................................................................................................... ES-7 ES.7 Operations and Ridership ............................................................................................................................... -

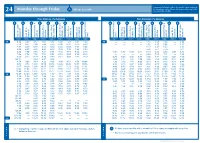

Monday Through Friday Mt

New printed schedules will not be issued if trips are adjusted Monday through Friday All trips accessible by five minutes or less. Please visit www.go-metro.com for the go smart... go METRO 24 most up-to-date schedule. 24 Mt. Lookout–Uptown–Anderson Riding Metro From Anderson / To Downtown From Downtown / To Anderson . 1 No food, beverages or smoking on Metro. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 2. Offer front seats to older adults and people with disabilities. METRO* PLUS 3. All Metro buses are 100% accessible for people 38X with disabilities. 46 UNIVERSITY OF 4. Use headphones with all audio equipment 51 CINCINNATI GOODMAN DANA MEDICAL CENTER HIGHLAND including cell phones. Anderson Center Station P&R Salem Rd. & Beacon St. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Liberty St. & Sycamore St. Square Government Area B Square Government Area B Liberty St. & Sycamore St. & Auburn Ave. McMillan St. Martin Luther King & Reading Rd. & Madison Ave. Observatory Ave. & Ave. Linwood Delta Ave. & Beechmont Ave. St. Corbly Salem Rd. & Beacon St. Anderson Center Station P&R 11 ZONE 2 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 1 ZONE 2 43 5. Fold strollers and carts. BURNET MT. LOOKOUT AM AM 38X 4:38 4:49 4:57 5:05 5:11 5:20 5:29 5:35 5:40 — — — — 4:10 4:15 4:23 — 4:35 OBSERVATORY READING O’BRYONVILLE LINWOOD 6. -

Balancing Passenger Preferences and Operational Efficiency in Network

Risk Averseness Regarding Short Connections in Airline Itinerary Choice AV020 Annual Meeting 2006 Submission Date: 01 April 2006, Word Count: 6902 By: Georg Theis Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Room 35-217 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Tel.: (617) 253-3507 Fax: (270) 968-5529 Email: [email protected] Thomas Adler Resource Systems Group 55 Railroad Row White River Junction, VT 05001 Tel.: (802) 295-4999 Fax: (802) 295-1006 Email: [email protected] John-Paul Clarke School of Aerospace Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0150 Tel: (404) 385-7206 Fax: (404) 894-2760 Email: [email protected] Moshe Ben-Akiva Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Room 1-181 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Tel.: (617) 253-5324 Fax: (617) 253-0082 Email: [email protected] Theis et al. 2 ABSTRACT Network airlines traditionally attempt to minimize passenger connecting times at hub airports based on the assumption that passengers prefer minimum scheduled elapsed times for their trips. Minimizing connecting times, however, creates peaks in hub airports’ schedules. These peaks are extremely cost intensive in terms of additional personnel, resources, runway capacity and schedule recovery. Consequently, passenger connecting times should only be minimized if the anticipated revenue gain of minimizing passenger connecting times is larger than the increase in operating cost, i.e. if this policy increases overall operating profit. This research analyzes to what extent a change in elapsed time impacts passenger itinerary choice and thus an airline’s market share. We extend an existing airline itinerary choice survey to test the assumption that passenger demand is affected by the length of connecting times. -

Matching the Speed of Technology with the Speed of Local Government: Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities

Final Report 1216 June 2020 Photo by Cait McCusker Matching the Speed of Technology with the Speed of Local Government: Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities Marc Schlossberg, Ph.D. Heather Brinton NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITIES nitc-utc.net MATCHING THE SPEED OF TECHNOLOGY WITH THE SPEED OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities Final Report NITC-RR-1216 by Marc Schlossberg, Professor Department of Planning, Public Policy and Management University of Oregon Heather Brinton, Director Environment and Natural Resources Law Center University of Oregon for National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) P.O. Box 751 Portland, OR 97207 June 2020 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. NITC-RR-1216 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date June 2020 Matching the Speed of Technology with the Speed of Local Government: Developing Codes and Policies Related to the Possible Impacts of New Mobility on Cities 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Marc Schlossberg Report No. Heather Brinton 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) University of Oregon 1209 University of Oregon 11. Contract or Grant No. Eugene, OR 97403 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) P.O. Box 751 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Portland, Oregon 97207 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract Advances in transportation technology such as the advent of scooter and bikeshare systems (micromobility), ridehailing, and autonomous vehicles (AV’s) are beginning to have profound effects not only on how we live, move, and spend our time in cities, but also on urban form and development itself. -

Covid-19 Questions & Answers Talking Points

COVID-19 QUESTIONS & ANSWERS TALKING POINTS (updated November 4, 2020) https://hawaiicovid19.com/travel/ https://www.gohawaii.com/travel-requirements Pre-Arrival Questions • What do I need to know about the pre-travel testing program? o The program is only for US mainland travelers arriving to any island. (Japan travel to begin November 6; International traveler may arrive from a US mainland airport.) o Adults and minors five years and older must take the pre-travel test. (Minors under five years do NOT need to take the pre-travel test.) o Test results accepted from ONLY Trusted Testing and Travel Partners. o Travelers are responsible for testing costs. o No commercial testing provided at Hawaii airports. o Flight delays will not impact the validity of test results. o The Department of Health will continue to update its site with information: https://hawaiicovid19.com/travel/ • Pre-Travel Process – Creating an Account o Prior to arrival, all adults (18 years and older) must create an online account on the state’s Safe Travels Program, create a profile, and enter trip information. Questions about the online form, step-by-step information on how to create a profile and trip, click HERE • For technical issues, go to https://ets.hawaii.gov/travelhelp/#For_Technical_Assistance and click the SUBMIT A REQUEST button and submit your issue. Or, you may call the Safe Travels Digital Platform Technical Service Desk (10 a.m. to 10 p.m. HST): 1-855-599-0888. Calls outside of working hours will go to voicemail and be returned the next business day. -

Selecting Layover Charging Locations for Electric Buses: Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Models

Selecting Layover Charging Locations for Electric Buses: Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Models Daniel McCabe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering University of Washington 2021 Committee: Xuegang Ban Chiwei Yan Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Civil and Environmental Engineering ©Copyright 2021 Daniel McCabe University of Washington Abstract Selecting Layover Charging Locations for Electric Buses: Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Models Daniel McCabe Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Xuegang Ban Civil and Environmental Engineering Public transit agencies across the United States are rapidly converting their bus fleets from diesel or hybrid powertrains to battery-electric propulsion systems. To realize the benefits of this transition while retaining acceptable quality of service and limiting capital costs, agencies must intelligently decide where to locate recharging infrastructure. While most agencies electrifying their fleets plan to install chargers at bases where buses are kept overnight, a question faced by many fleet operators is where to install layover chargers that provide additional energy while buses are in operation during the day. To address this challenge, this thesis presents two mixed-integer linear programming models that optimize the tradeoff between upfront charging infrastructure costs and operational performance in the form of trip delays and recovery times. A discrete-event simulation model is also developed to accurately quantify queue delays at heavily used chargers and better evaluate system performance under real-world variations in key parameters such as bus energy consumption per mile. The models are applied to a case study of South King County, WA, where an electric bus deployment is planned in the near future. -

Glossary of Transit Terminology

Glossary of Transit Terminology Source: Glossary of Transit Terminology, American Public Transit Association, Washington, DC, 1994. Base Period The period between the morning and evening peak periods when transit service is generally scheduled on a constant interval. Also known as “off-peak period.” Base Fare The price charged to one adult for one transit ride; excludes transfer charges, zone charges, express service charges, peak period surcharges and reduced fares. Deadhead The movement of a transit vehicle without passengers aboard. Downtime A period during which a vehicle is inoperative because of repairs or maintenance. Dwell Time The scheduled time a vehicle or train is allowed to discharge and take on passengers at a stop, including opening and closing doors. Fare Box Recovery Measure of the proportion of operating expenses Ratio covered by passenger fares; found by dividing fare box revenue by total operating expenses for each mode and/or systemwide. Fare Box Revenue Value of cash, tickets, tokens and pass receipts given by passengers as payment for rides; excludes charter revenue. Fare Elasticity The extent to which ridership responds to fare increases or decreases. Headway Time interval between vehicles moving in the same direction on a particular route. Kiss and Ride A place where commuters are driven and dropped off at a station to board a public transportation vehicle. Layover Time Time built into a schedule between arrival at the end of a route and the departure for the return trip, used for the recovery of delays and preparation for the return trip. Load Factor The ratio of passengers actually carried versus the D:\Courses\D2L\Glossary of Transit Terminology.doc 9/15/2004 1 total passenger capacity of a vehicle. -

Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making

Project No: FTA-VA-26-7222-2004.1 Federal United States Transit Department of August 2004 Administration Transportation CharacteristicsCharacteristics ofof BusBus RapidRapid TransitTransit forfor Decision-MakingDecision-Making Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES August 2004 COVERED BRT Demonstration Initiative Reference Document 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making 6. AUTHOR(S) Roderick B. Diaz (editor), Mark Chang, Georges Darido, Mark Chang, Eugene Kim, Donald Schneck, Booz Allen Hamilton Matthew Hardy, James Bunch, Mitretek Systems Michael Baltes, Dennis Hinebaugh, National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Lawrence Wnuk, Fred Silver, Weststart - CALSTART Sam Zimmerman, DMJM + Harris 8. -

How Much Do Consumers Really Value Air Travel On-Time Performance, and to What Extent Are Airlines Motivated to Improve Their On-Time Performance?

Economics of Transportation xxx (2017) 1–11 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Economics of Transportation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecotra How much do consumers really value air travel on-time performance, and to what extent are airlines motivated to improve their on-time performance? Philip G. Gayle a,*, Jules O. Yimga b a Kansas State University, Department of Economics, 322 Waters Hall, Manhattan, KS, 66506, USA b Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, School of Business, 3700 Willow Creek Road, Prescott, AZ, 86301, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT JEL classification: This paper estimates the value consumers place on air travel on-time performance (OTP), and the extent to which codes: L93 airlines are motivated to improve their OTP. We find robust evidence that consumers value OTP and are willing to L13 pay to avoid delays. Airlines can invest to improve OTP, but would independently choose to do so only if on-time fi Keywords: performance improvement leads to increases in pro tability. Using a methodology that does not require having Airline on-time performance actual cost data to draw inference on cost changes associated with improvement in OTP, we analyze airlines' Commercial aviation optimal OTP-improvement investment choice. The modeling framework allows us to provide estimates of OTP- related marginal investment costs per minute of improvement necessary to achieve specific percent reductions in arrival delay minutes from the current levels of arrival delay minutes observed in the data. 1. Introduction Remarkably, even with the flight on-time disclosure rule of 1987, the industry's OTP is still far below satisfactory levels. -

Downtown Layover/Office Building Alternatives Screening Report

SANDAG DOWNTOWN LAYOVER/OFFICE BUILDING ALTERNATIVES SCREENING REPORT APRIL 2015 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction and Study Purpose ................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Description of Alternatives .......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of the Layover Facility ........................................................................................................ 5 Project Alternatives ............................................................................................................................ 5 Site Alternatives ............................................................................................................................... 13 Site 1 ............................................................................................................................................. 13 Site 2 ............................................................................................................................................. 13 Site 3 ............................................................................................................................................. 14 Site 4 ............................................................................................................................................ -

Rail Transit Capacity

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 3 RAIL TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. RAIL CAPACITY BASICS ..................................................................................... 3-1 Introduction................................................................................................................. 3-1 Grouping ..................................................................................................................... 3-1 The Basics................................................................................................................... 3-2 Design versus Achievable Capacity ............................................................................ 3-3 Service Headway..................................................................................................... 3-4 Line Capacity .......................................................................................................... 3-5 Train Control Throughput....................................................................................... 3-5 Commuter Rail Throughput .................................................................................... 3-6 Station Dwells ......................................................................................................... 3-6 Train/Car Capacity...................................................................................................... 3-7 Introduction............................................................................................................. 3-7 Car Capacity...........................................................................................................