Bob Dylan and His "Late Style"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974 Tour with the Band

BOB DYLAN / THE BAND (a collectors guide to the 74 Tour) BOB DYLAN / THE BAND - a collectors guide to the 74 Tour “There are two problems with the 1974 tour: the tapes are crap and Dylan‟s performances are crap.” – C. Heylin, Telegraph 32 pg 86. Introduction This booklet / File (like the anonymous companion volume “Songs of the Underground” for RTR) is intended to document the audio resources available to collectors concerning the 1974 tour with the Band. It is intended to supplement and possibly correct the three major resources available to collectors (Krogsgaard, Dundas & Olof‟s files). Several PA tapes have emerged since Krogsgaard was last updated, and (I believe) there are errors in Dundas (concerning the PA tapes from 11 Feb 1974) that I wished to address. Additionally, none of these references (except for one full listing in Krogsgaard) include the Band sets. While details are difficult to obtain, I have included details of about three- quarters of the Band sets. It is hoped that readers on the web may contribute more information. I believe that the Band was a significant contributor to the 1974 Tour and should be included in any 1974 Tour documentation. I have also identified the sources for the Vinyl and CD bootlegs, where my resources allowed. Often the attributions on Bootlegs are misleading, incomplete or wrong. As an example „Before and After the Flood‟ claims to be from MSG NYC 30.1.1974 when it is actually a combination of the PA tapes from 31.1.74 (evening) and 11.2.74 (evening). -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

B Ob Dylan Nace En Duluth, Minnesota, Esta

... en la Biblioteca! LIBURUTEGIA / BIBLIOTECA ob Dylan nace en Duluth, Minnesota, Esta- dos Unidos el 24 de mayo de 1941 como Robert Allen Zimmerman. Músico, cantante, poeta y pintor, considerado como una de las figu- Bras más influyentes en la música popular del siglo XX y co- mienzos del XXI. Desde su niñez demostró un gran interés por la música y la poesía. Durante sus estudios universita- Bob Dylan (1962) rios entró en contacto con la música folk y la canción protes- Este es su primer disco, acústico y de gran influencia del folk y ta, y es entonces cuando adopta su nombre artístico, en ho- del blues, donde tan solo incluye dos temas propios, “Talkin' New menaje al poeta Dylan Thomas. En 1961 abandona la uni- York” y “Song to Woody”. versidad y se traslada a New York para dedicarse por completo a la música. El jo- ven cantante llamó la atención de las más importantes figuras del folk, como Pete The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963) Seeger o Joan Baez, próximos a los movimientos por los derechos civiles y contra la Con este disco da comienzo el cantautor de la protesta social y del guerra de Vietnam, y convencidos de que con sus canciones podían combatir el amor. Contiene el éxito “Blowin' in the Wind”, que se convirtió en comercialismo, la hipocresía, la injusticia, la desigualdad y la guerra. También Bob himno pacifista, así como otros temas imperecederos: “Girl from Dylan transmitía con sus letras, de alto contenido poético, mensajes que daban un the North Country”, “Masters of War”, “A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall”. -

2009 Europe Spring Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 2009 US SUMMER TOUR MAY Santa Monica, California Groove Masters Studios JUNE 11 Culver City, California Stage 15, Sony Pictures Studio, Michael Douglas Tribute JULY 1 Milwaukee, Wisconsin Marcus Amphitheatre 2 Sauget, Illinois GCS Ballpark 4 South Bend, Indiana Coveleski Stadium 5 Rothbury, Michigan The Odeum Stage, Double JJ Ranch, Rothbury Music Festival 8 Louisville, Kentucky Louisville Slugger Field 10 Dayton, Ohio Fifth Third Field 11 Eastlake, Ohio Classic Park 13 Washington, Pennsylvania CONSOL Energy Park 14 Allentown, Pennsylvania Coca-Cola Park 15 New Britain, Connecticut New Britain Stadium 17 Essex Junction, Vermont Champlain Valley Expo Center 18 Bethel, New York Bethel Woods Center For The Arts 19 Syracuse, New York Alliance Bank Stadium 21 Pawtucket, Rhode Island McCoy Stadium 23 Lakewood, New Jersey First Energy Park 24 Aberdeen, Maryland Ripken Stadium 25 Norfolk, Virginia Harbor Park 28 Durham, North Carolina Durham Bulls Athletic Park 29 Simpsonville, South Carolina Heritage Park Amphitheatre 30 Alpharetta, Georgia Verizon Wireless Amphitheatre at Encore Park 31 Orange Beach, Alabama The Amphitieater At The Wharf AUGUST 2 Houston, Texas Cynthia Woods Mitchell Pavilion, The Woodlands 4 Round Rock, Texas The Dell Diamond 5 Corpus Christi, Texas Whataburger Field 7 Grand Prairie, Texas Quik Trip Park 8 Lubbock, Texas Jones AT&T Stadium, Texas Tech University 9 Albuquerque, New Mexico Journal Pavilion 12 Lake Elsinore, California The Diamond 14 Fresno, California Chukchansi Park Bob Dylan: Still On The Road – 2009 US Summer Tour 15 Stockton, California Banner Island Park 16 Stateline, Nevada Harveys Lake Tahoe Outdoor Arena Bob Dylan: Still On The Road – 2009 US Summer Tour 31225 Groove Masters Studios Santa Monica, California May 2009 Christmas In The Heart recording sessions, produced by Jack Frost 1. -

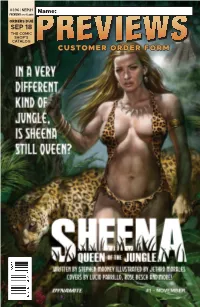

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Tangtewqpd 19 3 7-1987 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Saturday, 29 August at 8:30 The Boston Symphony Orchestra is pleased to present WYNTON MARSALIS An evening ofjazz. Week 9 Wynton Marsalis at this year's awards to win in the last four consecutive years. An exclusive CBS Masterworks and Columbia Records recording artist, Wynton made musical history at the 1984 Grammy ceremonies when he became the first instrumentalist to win awards in the categories ofjazz ("Best Soloist," for "Think of One") and classical music ("Best Soloist With Orches- tra," for "Trumpet Concertos"). He won Grammys again in both categories in 1985, for "Hot House Flowers" and his Baroque classical album. In the past four years he has received a combined total of fifteen nominations in the jazz and classical fields. His latest album, During the 1986-87 season Wynton "Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I," Marsalis set the all-time record in the represents the second complete album down beat magazine Readers' Poll with of the Wynton Marsalis Quartet—Wynton his fifth consecutive "Jazz Musician of on trumpet, pianist Marcus Roberts, the Year" award, also winning "Best Trum- bassist Bob Hurst, and drummer Jeff pet" for the same years, 1982 through "Tain" Watts. 1986. This was underscored when his The second of six sons of New Orleans album "J Mood" earned him his seventh jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton grew career Grammy, at the February 1987 up in a musical environment. He played ceremonies, making him the only artist first trumpet in the New -

Bob Dylan Good As I Been to You Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob Dylan Good As I Been To You mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Blues / Folk, World, & Country Album: Good As I Been To You Country: Europe Released: 1992 Style: Country Blues, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1738 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1374 mb WMA version RAR size: 1468 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 772 Other Formats: AAC DXD AC3 WAV AIFF AHX VOC Tracklist 1 Frankie & Albert 2 Jim Jones 3 Blackjack Davey 4 Canadee-I-O 5 Sittin' On Top Of The World 6 Little Maggie 7 Hard Times 8 Step It Up And Go 9 Tomorrow Night 10 Arthur McBride 11 You're Gonna Quit Me 12 Diamond Joe 13 Froggie Went A Courtin' Companies, etc. Distributed By – Sony Music Mastered At – Precision Mastering Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Made By – Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Pressed By – DADC Austria Credits Art Direction, Design – Dawn Patrol Mastered By – Stephen Marcussen Photography By [Front Cover] – Jimmy Wachtel Producer [Production Supervisor] – Debbie Gold Recorded By, Mixed By – Micajah Ryan Vocals, Guitar, Harmonica – Bob Dylan Notes Jewel case with 4-page booklet. Made in Austria. ℗ 1992 Sony Music Entertainment Inc. © 1992 Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Mastered at Precision Mastering, L.A. (US). Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 5 099747 271021 Barcode (Scanned): 5099747271021 Label Code: LC 0162 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1): DADC AUSTRIA 01-472710-10 22 B2 Matrix / Runout (Variant 2): DADC AUSTRIA 01-472710-10 22 A5 Matrix / Runout (Variant 3): DADC AUSTRIA 01-472710-10 -

Bob Denson Master Song List 2020

Bob Denson Master Song List Alphabetical by Artist/Band Name A Amos Lee - Arms of a Woman - Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight - Night Train - Sweet Pea Amy Winehouse - Valerie Al Green - Let's Stay Together - Take Me To The River Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You - Girl on Fire - No One Allman Brothers Band, The - Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More - Melissa - Ramblin’ Man - Statesboro Blues Arlen & Harburg (Isai K….and Eva Cassidy and…) - Somewhere Over the Rainbow Avett Brothers - The Ballad of Love and Hate - Head Full of DoubtRoad Full of Promise - I and Love and You B Bachman Turner Overdrive - Taking Care Of Business Band, The - Acadian Driftwood - It Makes No Difference - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) - Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The - Ophelia - Up On Cripple Creek - Weight, The Barenaked Ladies - Alcohol - If I Had A Million Dollars - I’ll Be That Girl - In The Car - Life in a Nutshell - Never is Enough - Old Apartment, The - Pinch Me Beatles, The - A Hard Day’s Night - Across The Universe - All My Loving - Birthday - Blackbird - Can’t Buy Me Love - Dear Prudence - Eight Days A Week - Eleanor Rigby - For No One - Get Back - Girl Got To Get You Into My Life - Help! - Her Majesty - Here, There, and Everywhere - I Saw Her Standing There - I Will - If I Fell - In My Life - Julia - Let it Be - Love Me Do - Mean Mr. Mustard - Norwegian Wood - Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da - Polythene Pam - Rocky Raccoon - She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - She Loves You - Something - Things We Said Today - Twist and Shout - With A Little Help From My Friends - You’ve -

Black Women, Natural Hair, and New Media (Re)Negotiations of Beauty

“IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT “IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe At the intersection of social media, a trend in organic products, and an interest in do-it-yourself culture, the late 2000s opened a space for many Black American women to stop chemically straightening their hair via “relaxers” and begin to wear their hair natural—resulting in an Internet-based cultural phenomenon known as the “natural hair movement.” Within this context, conversations around beauty standards, hair politics, and Black women’s embodiment have flourished within the public sphere, largely through YouTube, social media, and websites. My project maps these conversations, by exploring contemporary expressions of Black women’s natural hair within cultural production. Using textual and content analysis, I investigate various sites of inquiry: natural hair product advertisements and internet representations, as well as the ways hair texture is evoked in recent song lyrics, filmic scenes, and non- fiction prose by Black women. Each of these “hair moments” offers a complex articulation of the ways Black women experience, share, and negotiate the socio-historically fraught terrain that is racialized body politics