Radiation and Your Patient: a Guide for Medical Practitioners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exposure to Carcinogens and Work-Related Cancer: a Review of Assessment Methods

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work ISSN: 1831-9343 Exposure to carcinogens and work-related cancer: A review of assessment methods European Risk Observatory Report Exposure to carcinogens and work-related cancer: A review of assessment measures Authors: Dr Lothar Lißner, Kooperationsstelle Hamburg IFE GmbH Mr Klaus Kuhl (task leader), Kooperationsstelle Hamburg IFE GmbH Dr Timo Kauppinen, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health Ms Sanni Uuksulainen, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health Cross-checker: Professor Ulla B. Vogel from the National Working Environment Research Centre in Denmark Project management: Dr Elke Schneider - European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers, or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet ( 48TU http://europa.euU48T). Cataloguing data can be found on the cover of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2014 ISBN: 978-92-9240-500-7 doi: 10.2802/33336 Cover pictures: (clockwise): Anthony Jay Villalon (Fotolia); ©Roman Milert (Fotolia); ©Simona Palijanskaite; ©Kari Rissa © European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2014 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work – EU-OSHA 1 Exposure to carcinogens and work-related cancer: -

Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life

Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life Nuclear Energy in Everyday Life Understanding Radioactivity and Radiation in our Everyday Lives Radioactivity is part of our earth – it has existed all along. Naturally occurring radio- active materials are present in the earth’s crust, the floors and walls of our homes, schools, and offices and in the food we eat and drink. Our own bodies- muscles, bones and tissues, contain naturally occurring radioactive elements. Man has always been exposed to natural radiation arising from earth as well as from outside. Most people, upon hearing the word radioactivity, think only about some- thing harmful or even deadly; especially events such as the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, or the Chernobyl Disaster of 1986. However, upon understanding radiation, people will learn to appreciate that radia- tion has peaceful and beneficial applications to our everyday lives. What are atoms? Knowledge of atoms is essential to understanding the origins of radiation, and the impact it could have on the human body and the environment around us. All materi- als in the universe are composed of combination of basic substances called chemical elements. There are 92 different chemical elements in nature. The smallest particles, into which an element can be divided without losing its properties, are called atoms, which are unique to a particular element. An atom consists of two main parts namely a nu- cleus with a circling electron cloud. The nucleus consists of subatomic particles called protons and neutrons. Atoms vary in size from the simple hydro- gen atom, which has one proton and one electron, to large atoms such as uranium, which has 92 pro- tons, 92 electrons. -

Carcinogens Are Mutagens

-Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 70, No. 8, pp. 2281-2285, August 1973 Carcinogens are Mutagens: A Simple Test System Combining Liver Homogenates for Activation and Bacteria for Detection (frameshift mutagens/aflatoxin/benzo(a)pyrene/acetylaminofluorene) BRUCE N. AMES, WILLIAM E. DURSTON, EDITH YAMASAKI, AND FRANK D. LEE Biochemistry Department, University of California, Berkeley, Calif. 94720 Contributed by Bruce N. Ames, May 14, 1973 ABSTRACT 18 Carcinogens, including aflatoxin Bi, methylsulfoxide (Me2SO), spectrophotometric grade, was ob- benzo(a)pyrene, acetylaminofluorene, benzidine, and di- tained from Schwarz/Mann, sodium phenobarbital from methylamino-trans-stilbene, are shown to be activated by liver homogenates to form potent frameshift mutagens. Mallinckrodt, aflatoxin B1 from Calbiochem, and 3-methyl- We believe that these carcinogens have in common a ring cholanthrene from Eastman; 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene system sufficiently planar for a stacking interaction with was a gift of P. L. Grover. Schuchardt (Munich) was the DNA base pairs and a part of the molecule capable of being source for the other carcinogens. metabolized to a reactive group: these structural features are discussed in terms of the theory of frameshift muta- Bacterial Strains used are mutants of S. typhimurium LT-2 genesis. We propose that these carcinogens, and many have been discussed in detail others that are mutagens, cause cancer by somatic muta- and (2). tion. A simple, inexpensive, and extremely sensitive test for Source Liver. Male rats (Sprague-Dawley/Bio-1 strain, detection of carcinogens as mutagens is described. It con- of sists of the use of a rat or human liver homogenate for Horton Animal Laboratories) were maintained on Purina carcinogen activation (thus supplying mammalian metab- laboratory chow. -

Radiation Protection in Paediatric Radiology at Medical Physicists and Regulators

Safety Reports Series The Fundamental Safety Principles and the IAEA's General Safety Rquirements publication, Radiation Protection and Safety of Radiation Safety Reports Series Sources: International Basic Safety Standards (BSS) require the radiological protection of patients undergoing medical exposures No.71 through justification of the procedures involved No. and through optimization. This publication 71 provides guidance to radiologists, other clinicians and radiographers/technologists involved in diagnostic procedures using ionizing radiation with children and adolescents. It is also aimed Radiation Protection in Paediatric Radiology at medical physicists and regulators. The focus is on the measures necessary to provide protection from the effects of radiation using the principles established in the BSS and according to the priority given to this issue. Radiation Protection in Paediatric Radiology INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA ISBN 978–92–0–125710–9 ISSN 1020–6450 RELATED PUBLICATIONS IAEA SAFETY STANDARDS AND RELATED PUBLICATIONS RADIATION PROTECTION IN NEWER MEDICAL IMAGING TECHNIQUES: PET/CT IAEA SAFETY STANDARDS Safety Reports Series No. 58 STI/PUB/1343 (41 pp.; 2008) Under the terms of Article III of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to establish or adopt ISBN 978–92–0–106808–8 Price: €28.00 standards of safety for protection of health and minimization of danger to life and property, and to provide for the application of these standards. The publications by means of which the IAEA establishes standards are issued in the APPLYING RADIATION SAFETY STANDARDS IN DIAGNOSTIC IAEA Safety Standards Series. This series covers nuclear safety, radiation safety, transport RADIOLOGY AND INTERVENTIONAL PROCEDURES USING X RAYS safety and waste safety. -

RADIOGRAPHY to Prepare Individuals to Become Registered Radiologic Technologists

RADIOGRAPHY To prepare individuals to become Registered Radiologic Technologists. THE WORKFORCE CAPITAL This two-year, advanced medical program trains students in radiography. Radiography uses radiation to produce images of tissues, organs, bones and vessels of the body. The radiographer is an essential member of the health care team who works in a variety of settings. Responsibili- ties include accurately positioning the patient, producing quality diagnostic images, maintaining equipment and keeping computerized records. This certificate program of specialized training focuses on each of these responsibilities. Graduates are eligible to apply for the national credential examination to become a registered technologist in radiography, RT(R). Contact Student Services for current tuition rates and enrollment information. 580.242.2750 Mission, Goals, and Student Learning Outcomes Program Effectiveness Data Radiography Program Guidelines (Policies and Procedures) “The programs at Autry prepare you for the workforce with no extra training needed after graduation.” – Kenedy S. autrytech.edu ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES 1201 West Willow | Enid, Oklahoma, 73703 | 580.242.2750 | autrytech.edu COURSE LENGTH Twenty-four-month daytime program î August-July î Monday-Friday Academic hours: 8:15am-3:45pm Clinical hours: Eight-hour shifts between 7am-5pm with some ADMISSION PROCEDURES evening assignments required Applicants should contact Student Services at Autry Technology Center to request an information/application packet. Applicants who have a completed application on file and who have met entrance requirements will be considered for the program. Meeting ADULT IN-DISTRICT COSTS the requirements does not guarantee admission to the program. Qualified applicants will be contacted for an interview, and class Year One: $2732 (Additional cost of books and supplies approx: $1820) selection will be determined by the admissions committee. -

ACR–SPR-STR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Chest Radiography

The American College of Radiology, with more than 30,000 members, is the principal organization of radiologists, radiation oncologists, and clinical medical physicists in the United States. The College is a nonprofit professional society whose primary purposes are to advance the science of radiology, improve radiologic services to the patient, study the socioeconomic aspects of the practice of radiology, and encourage continuing education for radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and persons practicing in allied professional fields. The American College of Radiology will periodically define new practice parameters and technical standards for radiologic practice to help advance the science of radiology and to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the United States. Existing practice parameters and technical standards will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated. Each practice parameter and technical standard, representing a policy statement by the College, has undergone a thorough consensus process in which it has been subjected to extensive review and approval. The practice parameters and technical standards recognize that the safe and effective use of diagnostic and therapeutic radiology requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in each document. Reproduction or modification of the published practice parameter and technical standard by those entities not providing these services is not authorized. Revised 2017 (Resolution 2)* ACR–SPR–STR PRACTICE PARAMETER FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF CHEST RADIOGRAPHY PREAMBLE This document is an educational tool designed to assist practitioners in providing appropriate radiologic care for patients. Practice Parameters and Technical Standards are not inflexible rules or requirements of practice and are not intended, nor should they be used, to establish a legal standard of care1. -

Estimation of the Collective Effective Dose to the Population from Medical X-Ray Examinations in Finland

Estimation of the collective effective dose to the population from medical x-ray examinations in Finland Petra Tenkanen-Rautakoskia, Hannu Järvinena, Ritva Blya aRadiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (STUK), PL 14, 00880 Helsinki, Finland Abstract. The collective effective dose to the population from all x-ray examinations in Finland in 2005 was estimated. The numbers of x-ray examinations were collected by a questionnaire to the health care units (response rate 100 %). The effective doses in plain radiography were calculated using a Monte Carlo based program (PCXMC), as average values for selected health care units. For computed tomography (CT), weighted dose length product (DLPw) in a standard phantom was measured for routine CT protocols of four body regions, for 80 % of CT scanners including all types. The effective doses were calculated from DPLw values using published conversion factors. For contrast-enhanced radiology and interventional radiology, the effective dose was estimated mainly by using published DAP values and conversion factors for given body regions. About 733 examinations per 1000 inhabitants (excluding dental) were made in 2005, slightly less than in 2000. The proportions of plain radiography, computed tomography, contrast-enhanced radiography and interventional procedures were about 92, 7, 1 and 1 %, respectively. From 2000, the frequencies (number of examinations per 1000 inhabitants) of plain radiography and contrast-enhanced radiography have decreased about 8 and 33 %, respectively, while the frequencies of CT and interventional radiology have increased about 28 and 38 %, respectively. The population dose from all x-ray examinations is about 0,43 mSv per person (in 1997 0,5 mSv). -

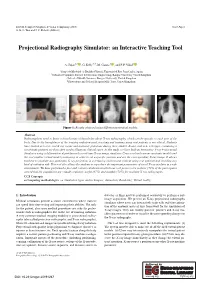

Projectional Radiography Simulator: an Interactive Teaching Tool

EG UK Computer Graphics & Visual Computing (2019) Short Paper G. K. L. Tam and J. C. Roberts (Editors) Projectional Radiography Simulator: an Interactive Teaching Tool A. Sujar1,2 , G. Kelly3,4, M. García1 , and F. P. Vidal2 1Grupo de Modelado y Realidad Virtual, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Spain 2School of Computer Science & Electronic Engineering, Bangor University United Kingdom 3School of Health Sciences, Bangor University, United Kingdom 4Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust, United Kingdom Figure 1: Results obtained using different anatomical models. Abstract Radiographers need to know a broad range of knowledge about X-ray radiography, which can be specific to each part of the body. Due to the harmfulness of the ionising radiation used, teaching and training using real patients is not ethical. Students have limited access to real X-ray rooms and anatomic phantoms during their studies. Books, and now web apps, containing a set of static pictures are then often used to illustrate clinical cases. In this study, we have built an Interactive X-ray Projectional Simulator using a deformation algorithm with a real-time X-ray image simulator. Users can load various anatomic models and the tool enables virtual model positioning in order to set a specific position and see the corresponding X-ray image. It allows teachers to simulate any particular X-ray projection in a lecturing environment without using real patients and avoiding any kind of radiation risk. This tool also allows the students to reproduce the important parameters of a real X-ray machine in a safe environment. We have performed a face and content validation in which our tool proves to be realistic (72% of the participants agreed that the simulations are visually realistic), useful (67%) and suitable (78%) for teaching X-ray radiography. -

Sources, Effects and Risks of Ionizing Radiation

SOURCES, EFFECTS AND RISKS OF IONIZING RADIATION United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation UNSCEAR 2016 Report to the General Assembly, with Scientific Annexes UNITED NATIONS New York, 2017 NOTE The report of the Committee without its annexes appears as Official Records of the General Assembly, Seventy-first Session, Supplement No. 46 and corrigendum (A/71/46 and Corr.1). The report reproduced here includes the corrections of the corrigendum. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The country names used in this document are, in most cases, those that were in use at the time the data were collected or the text prepared. In other cases, however, the names have been updated, where this was possible and appropriate, to reflect political changes. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.17.IX.1 ISBN: 978-92-1-142316-7 eISBN: 978-92-1-060002-6 © United Nations, January 2017. All rights reserved, worldwide. This publication has not been formally edited. Information on uniform resource locators and links to Internet sites contained in the present publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issue. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. -

Radiation and Risk: Expert Perspectives Radiation and Risk: Expert Perspectives SP001-1

Radiation and Risk: Expert Perspectives Radiation and Risk: Expert Perspectives SP001-1 Published by Health Physics Society 1313 Dolley Madison Blvd. Suite 402 McLean, VA 22101 Disclaimer Statements and opinions expressed in publications of the Health Physics Society or in presentations given during its regular meetings are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Health Physics Society, the editors, or the organizations with which the authors are affiliated. The editor(s), publisher, and Society disclaim any responsibility or liability for such material and do not guarantee, warrant, or endorse any product or service mentioned. Official positions of the Society are established only by its Board of Directors. Copyright © 2017 by the Health Physics Society All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form, in an electronic retrieval system or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America SP001-1, revised 2017 Radiation and Risk: Expert Perspectives Table of Contents Foreword……………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 2 A Primer on Ionizing Radiation……………………………………………………………………………... 6 Growing Importance of Nuclear Technology in Medicine……………………………………….. 16 Distinguishing Risk: Use and Overuse of Radiation in Medicine………………………………. 22 Nuclear Energy: The Environmental Context…………………………………………………………. 27 Nuclear Power in the United States: Safety, Emergency Response Planning, and Continuous Learning…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 33 Radiation Risk: Used Nuclear Fuel and Radioactive Waste Disposal………………………... 42 Radiation Risk: Communicating to the Public………………………………………………………… 45 After Fukushima: Implications for Public Policy and Communications……………………. 51 Appendix 1: Radiation Units and Measurements……………………………………………………. 57 Appendix 2: Half-Life of Some Radionuclides…………………………………………………………. 58 Bernard L. -

Toxicological Profile for Radon

RADON 205 10. GLOSSARY Some terms in this glossary are generic and may not be used in this profile. Absorbed Dose, Chemical—The amount of a substance that is either absorbed into the body or placed in contact with the skin. For oral or inhalation routes, this is normally the product of the intake quantity and the uptake fraction divided by the body weight and, if appropriate, the time, expressed as mg/kg for a single intake or mg/kg/day for multiple intakes. For dermal exposure, this is the amount of material applied to the skin, and is normally divided by the body mass and expressed as mg/kg. Absorbed Dose, Radiation—The mean energy imparted to the irradiated medium, per unit mass, by ionizing radiation. Units: rad (rad), gray (Gy). Absorbed Fraction—A term used in internal dosimetry. It is that fraction of the photon energy (emitted within a specified volume of material) which is absorbed by the volume. The absorbed fraction depends on the source distribution, the photon energy, and the size, shape and composition of the volume. Absorption—The process by which a chemical penetrates the exchange boundaries of an organism after contact, or the process by which radiation imparts some or all of its energy to any material through which it passes. Self-Absorption—Absorption of radiation (emitted by radioactive atoms) by the material in which the atoms are located; in particular, the absorption of radiation within a sample being assayed. Absorption Coefficient—Fractional absorption of the energy of an unscattered beam of x- or gamma- radiation per unit thickness (linear absorption coefficient), per unit mass (mass absorption coefficient), or per atom (atomic absorption coefficient) of absorber, due to transfer of energy to the absorber. -

Digital and Advanced Imaging Equipment

CHAPTER 9 Digital and Advanced Imaging Equipment KEY TERMS active matrix array direct-to-digital radiographic systems photostimulated luminescence amorphous dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry picture archiving and communication analog-to-digital converter F-center system aspect ratio fill factor preprocessing cinefluorography frame rate postprocessing computed radiography image contrast refresh rate detective quantum efficiency image enhancement special procedures laboratory Digital Imaging and Communications image management and specular reflection in Medicine group communication system teleradiology digital fluoroscopy image restoration thin-film transistor digital radiography interpolation window level digital subtraction angiography liquid crystal display window width digital x-ray radiogrammetry Nyquist frequency OBJECTIVES At the completion of this chapter the reader should be able to do the following: • Describe the basic methods of obtaining digital cathode-ray tube cameras, videotape and videodisc radiographs recorders, and cinefluorographic equipment and discuss • State the advantages and disadvantages of digital the quality control procedures for each radiography versus conventional film/screen • Describe the various types of electronic display devices radiography and discuss the applicable quality control procedures • Discuss the quality control procedures for evaluating • Explain the basic image archiving and management digital radiographic systems networks and discuss the applicable quality control • Describe the basic methods