Setting the Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

National Historical Park Pennsylvania

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park Pennsylvania Hall was begun in the spring of 1732, when from this third casting is the one you see In May 1775, the Second Continental Con The Constitutional Convention, 1787 where Federal Hall National Memorial now ground was broken. today.) gress met in the Pennsylvania State House stands. Then, in 1790, it came to Philadel Edmund Woolley, master carpenter, and As the official bell of the Pennsylvania (Independence Hall) and decided to move The Articles of Confederation and Perpet phia for 10 years. Congress sat in the new INDEPENDENCE ual Union were drafted while the war was in Andrew Hamilton, lawyer, planned the State House, the Liberty Bell was intended to from protest to resistance. Warfare between County Court House (now known as Con building and supervised its construction. It be rung on public occasions. During the the colonists and British troops already had progress. They were agreed to by the last of gress Hall) and the United States Supreme NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK was designed in the dignity of the Georgian Revolution, when the British Army occupied begun in Massachusetts. In June the Con the Thirteen States and went into effect in Court in the new City Hall. In Congress period. Independence Hall, with its wings, Philadelphia in 1777, the bell was removed gress chose George Washington to be Gen the final year of the war. Under the Arti Hall, George Washington was inaugurated has long been considered one of the most to Allentown, where it was hidden for almost eral and Commander in Chief of the Army, cles, the Congress met in various towns, only for his second term as President. -

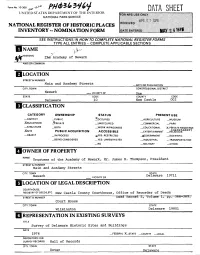

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

Dinner with Ben Franklin: the Origins of the American Philosophical Society1

Dinner with Ben Franklin: The Origins of the American Philosophical Society1 LINDA GREENHOUSE President, American Philosophical Society Joseph Goldstein Lecturer in Law, Yale University e gather today to celebrate the American Philosophical Soci- ety’s 275th anniversary. But in fact, our story begins 16 years W earlier, in 1727, here in Philadelphia, and it is that origin story that is my focus this afternoon. The measure of my success in telling that story will be whether at the end of the next 20 minutes you will be left wishing—as I was when I first encountered this tale—that you could have been a guest at the young Benjamin Franklin’s table during those years when the notion of the APS was taking shape in his incredibly fertile mind. In 1727, Franklin was 21 years old and working in Philadelphia as the manager of a printing house. He invited those whom he called his “ingenious acquaintances” to join a “club of mutual improvement” that he called The Junto, from the Latin iungere, meaning “to join.”2 Members of the Junto met on Friday evenings in a local tavern. This was not a casual invitation. Here is how Franklin described the club in his Autobiography: The Rules I drew up, requir’d that every Member in his Turn should produce one or more Queries on any Point of Morals, Poli- tics or Natural Philosophy, to be discuss’d by the Company, and once in three Months produce and read an Essay of his own Writing on any Subject he pleased. Our Debates were to be under the Direction of a President, and to be conducted in the sincere Spirit of Enquiry after Truth, without fondness for Dispute, or Desire of Victory; and to prevent Warmth, all Expressions of Posi- tiveness in Opinion, or of direct Contradiction, were after some time made contraband & prohibited under small pecuniary Penalties.3 1 Read 26 April 2018. -

A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1979 A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776 John Thomas anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation anderson, John Thomas, "A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776" (1979). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625075. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tdv7-hy77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN WITHERSPOON * L FROM 1723 TO 1776 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *y John Thomas Anderson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, September 1979 John Michael McGiffert (J ^ j i/u?wi yybirvjf \}vr James J. Thompson, Jr. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION....................... ill TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... v ABSTRACT........... vi INTRODUCTION................. 2 CHAPTER I. "OUR NOBLE, VENERABLE, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": JOHN WITHERSPOON IN SCOTLAND, 1723-1768 . ............ 5 CHAPTER II. "AN EQUAL REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": WITHERSPOON IN NEW JERSEY, 1768-1776 37 NOTES . -

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin 25

YPi AAAAAAJL 'imjij i=W AurCS'.ORAPHYOF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN t: > ' '^ \^^ -^ • ^JJ^I yfv Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/autobiographyofb00fran5 V Autobiography or Benjaa\in Tranklin Chicago W. B. CONKEY COMPANY THE IIW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY gG819^B ASTCR, LEN&X AND TfLOm HtfUNDAliONS B 1044 L LIFE or DR. FRANKLIN / My deab Sok, I HAVE amused myself with collecting some little anecdotes of my family. You may re- member the inquiries I made, when you were with me in England, among such of my rela- tions as were then living ; and the journey J undertook for that purpose. To be ac- quainted with the particulars of my parent- age and life, many of which are unknown to you, I flatter myself will afford the same pleasure to you as to me. I shall relate them upon paper : it will be an agreeable employ- ment of a week's uninterrupted leisure, which I promise myself during my present retire- ment in the country. There are also other motives which induce me to the undertaking. 4 3YS5 a 4 LI Ft: OF DR.. FRANKLIlSf. From the bosom of poverty and obscurity, in which I drew my first breath, and spent my earliest years, I have raised myself to a state of opulence and to some degree of celebrity in the world. A constant good fortune has attended me through every period of life to my present advanced age ; and my descend- ants may be desirous of learning what were the means of which I made use, and which, thanks to the assisting hand of Providence, have proved so eminently successful. -

Pennsylvania Pennsylvania

NHL:: flfrrica at Work, Science^Work NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK -.—-^f——————————————— Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Pennsylvania COUN TY: . T1 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Philadelphia AATJOML FiSTOI^VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM _______FOR NPS USE ONL_Y ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: American Philosophical Society Hall AND/ OR HISTORIC: AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY HALL STREET ANQNUMBER: Independence Square CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Philadelphia 003 COUNTY: Pennsylvania 42 Philadelphia 101 ACCESSIBLE OWNERSH.P STATUS, TATIK TO THE PUBLIC Q District Building D Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: Q) In Process il . , K] Restricted D Site Structure 53 Private Unoccupied "^ D Both | | Being Considered d Unrestricted Object LJr~ i PreservationD worki ' — ' in progress PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) O Agricultural Q Government Q) Park l~l Transportation 1 1 Comments [^.Commercial 1 1 Industrial [~| Private Residence D Other (Specify) 1 1 Educational 1 1 Military [ | Religious 1 1 Entertainment tZ] Museum jgj Scientific OWNER'S NAME: American Philosophical Society, Dr. George W. Corner, Executive Officer STREET AND NUMBER: American Philosophical Society Hall sylvania CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Philadelphia Pennsylvania 42 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: 13 V Dept. of Records H- STREET AND NUMBER: h-> City Hall s.CD CITY OR TOWN: -dh-> *-*•& Phi1adeIphia ____^ W I TITLE OF SURVEY: Historic American Building Survey -

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: a Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: A Brief History of The Library Company of Philadelphia On July 1, 1731, Benjamin Franklin and a number of his fellow members of the Junto drew up "Articles of Agreement" to found a library. The Junto was a discussion group of young men seeking social, economic, intellectual, and political advancement. When they foundered on a point of fact, they needed a printed authority to settle the divergence of opinion. In colonial Pennsylvania at the time there were not many books. Standard English reference works were expensive and difficult to obtain. Franklin and his friends were mostly mechanics of moderate means. None alone could have afforded a representative library, nor, indeed, many imported books. By pooling their resources in pragmatic Franklinian fashion, they could. The contribution of each created the book capital of all. Fifty subscribers invested forty shillings each and promised to pay ten shillings a year thereafter to buy books and maintain a shareholder's library. Thus "the Mother of all American Subscription Libraries" was established. A seal was decided upon with the device: "Two Books open, Each encompass'd with Glory, or Beams of Light, between which water streaming from above into an Urn below, thence issues at many Vents into lesser Urns, and Motto, circumscribing the whole, Communiter Bona profundere Deum est." This translates freely: "To pour forth benefits for the common good is divine." The silversmith Philip Syng engraved the seal. The first list of desiderata to stock the Tin Suggestion shelves was sent to London on March 31, 1732, and by autumn that Box, ca. -

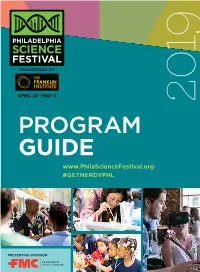

Program Guide #Getnerdyphl

APRIL 26 – MAY 4 2019 PROGRAM GUIDE www.PhilaScienceFestival.org #GETNERDYPHL PRESENTING SPONSOR 9 DAYS. OVER 60 EVENTS. Welcome to The Philadelphia Science MORE THAN 75,000 ATTENDEES. Festival—a nine-day, community-wide 1 GOAL! celebration of science! Together, The Franklin Institute and 200 collaborators from the region's leading educational, cultural, and scientific institutions are joining forces to educate, inspire, and excite the Delaware Valley about the science present in our everyday lives. From vegetable gardens to beer gardens; from public parks to fossil parks; and from chemistry labs to maker spaces— we invite you to get curious, get creative, and most of all... #GetNerdyPHL | PhilaScienceFestival.org We are grateful to FMC for generously supporting the Philadelphia Science Festival as Presenting Sponsor in 2019. learn more at PhilaScienceFestival.org 2 3 FESTIVAL EVENTS AT A GLANCE PAGE 7 PAGE 8-10 PAGE 11 PAGE 12-15 PAGE 16-17 PAGE 18-19 PAGE 20 PAGE 21 PAGE 22 PAGE 23 PRE FRI SAT SUN SUN MON TUES WED THURS FRI FESTIVAL APRIL APRIL APRIL APRIL APRIL APRIL MAY MAY MAY EVENT 26 27 28 28 29 30 1 2 3 SAT Citywide Science Be a Murder Science Science Science Science Electric MARCH Star Party Saturday Scientist! at the After After After in the Jellyfish 30 Various at Rutgers Various Mütter®: School School School National at the times 11 am–1 pm Times Workplace 3:30– 3:30– 3:30 – Park Philly Tech Science Woes 5:30 pm 5:30 pm 5:30 pm Week Various Various 10 am– at the Locations Rutgers Locations 2–6 pm Greater Andorra, Fumo Kickoff Ballpark University Olney, 2 pm 6–8 pm Mütter Eastwick, In- Family, Indepen- Science Star Party POP Philadelphia Museum dependence, Holmes- dence Science Activities After Party Science in the City of the and Joseph burg, and National History at 2:30 pm in the Park Institute, 10 pm– College of E.