From Useful Knowledge to Rational Amusement: Museums in Early America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

Essay Exhibit and Book Review

Essay Exhibit and Book Review: The PealeFamily: Creation of a Legacy 1770-1870, Lillian B. Miller, Editor (New York: Abbeyville Press, 1996, $65.00). Traveling Exhibit: Philadelphia Museum of Art (November 1996-Janu- ary 1997); M. H. DeYoung Museum, San Francisco (January-April 1997); Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D. C. (April-July, 1997). Phoebe Lloyd DepartmentofArt History, Texas Tech University In her forward to The Peale Family: Creationofa Legacy, 1770-1870, Ann Van Devanter Townsend raises the question "how would the academic com- munity refer to this important body of scholarship for years to come?" Townsend is President of The Trust for Museum Exhibitions, a nonprofit organization that sponsored the book and Peale family exhibition at three host museums. As Trust President and initiator of the exhibitions, Townsend may well pon- der. Her leading players, Lillian B. Miller, Sidney Hart, and David C. Ward, are not trained art historians. Their crossover from cultural and social history to art history reveals how different the disciplines are and how inapplicable the expertise of the social historian can be. Part of what is lacking in this enterprise of exhibition-cum-text is accountability: to the primacy of the im- age; to the established methodologies of art history; to the kind of scholarly apparatus that substantiates an attribution. Even where the two disciplines should coalesce, there is a lack of accountability: to the bare bones of historical fact, to the Peale family's primary source material stored in the vault at the American Philosophical Society; to the intellectual property of others and in- cluding the work done by those who garnered the footnote information for the now four-volume The Selected Papers of Charles Wil/on Peale, of which Miller is editor. -

HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA J\Roi^RISTOWN

BULLETIN joffAe- HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA J\rOI^RISTOWN £omery PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY AT IT5 R00M5 IS EAST PENN STREET NORRI5TOWN.PA. OCTOBER, 1939 VOLUME II NUMBER 1 PRICE 50 CENTS Historical Society of Montgomery County OFFICERS Nelson P. Fegley, Esq., President S. Cameron Corson, First Vice-President Mrs. John Faber Miller, Second Vice-President Charles Harper Smith, Third Vice-President Mrs. Rebecca W. Brecht, Recording Secretary Ella Slinglupp, Corresponding Secretary Annie B. Molony, Financial Secretary Lyman a. Kratz, Treasurer Emily K. Preston, Librarian TRUSTEES Franklin A. Stickler, Chairman Mrs. A. Conrad Jones Katharine Preston H. H. Ganser Floyd G. Frederick i David Rittenhouse THE BULLETIN of the Historical Society of Montgomery County Published Semi-Anrvmlly — October and April Volume II October, 1939 Number 1 CONTENTS Dedication of the David Rittenhouse Marker, June 3, 1939 3 David Rittenhouse, LL.D., F.R.S. A Study from ContemporarySources, Milton Rubincam 8 The Lost Planetarium of David Ritten house James K. Helms 31 The Weberville Factory Charles H. Shaw 35 The Organization of Friends Meeting at Norristown Helen E. Richards 39 Map Making and Some Maps of Mont gomery County Chester P. Cook 51 Bible Record (Continued) 57 Reports 65 Publication Committee Dr. W. H. Reed, Chairman Charles R. Barker Hannah Gerhard Chester P. Cook Bertha S. Harry Emily K. Preston, Editor 1 Dedication of the David Rittenhouse Marker June 3, 1939 The picturesque farm of Mr. Herbert T. Ballard, Sr., on Germantown Pike, east of Fairview Village, in East Norriton township, was the scene of a notable gathering, on June 3, 1939, the occasion being the dedication by the Historical So ciety of Montgomery County of the marker commemorating the observation of the transit of Venus by the astronomer, David Rittenhouse, on nearby ground, and on the same month and day, one hundred and seventy years before. -

Artists` Picture Rooms in Eighteenth-Century Bath

ARTISTS' PICTURE ROOMS IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BATH Susan Legouix Sloman In May 1775 David Garrick described to Hannah More the sense of well being he experienced in Bath: 'I do this, & do that, & do Nothing, & I go here and go there and go nowhere-Such is ye life of Bath & such the Effects of this place upon me-I forget my Cares, & my large family in London, & Every thing ... '. 1 The visitor to Bath in the second half of the eighteenth century had very few decisions to make once he was safely installed in his lodgings. A well-established pattern of bathing, drinking spa water, worship, concert and theatre-going and balls meant that in the early and later parts of each day he was likely to be fully occupied. However he was free to decide how to spend the daylight hours between around lOam when the company generally left the Pump Room and 3pm when most people retired to their lodgings to dine. Contemporary diaries and journals suggest that favourite daytime pursuits included walking on the parades, carriage excursions, visiting libraries (which were usually also bookshops), milliners, toy shops, jewellers and artists' showrooms and of course, sitting for a portrait. At least 160 artists spent some time working in Bath in the eighteenth century,2 a statistic which indicates that sitting for a portrait was indeed one of the most popular activities. Although he did not specifically have Bath in mind, Thomas Bardwell noted in 1756, 'It is well known, that no Nation in the World delights so much in Face-painting, or gives so generous Encouragement to it as our own'.3 In 1760 the Bath writer Daniel Webb noted 'the extraordinary passion which the English have for portraits'.4 Andre Rouquet in his survey of The Present State of the Arts in England of 1755 described how 'Every portrait painter in England has a room to shew his pictures, separate from that in which he works. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition

In the Shadow of His Father: Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition URING His LIFETIME, Rembrandt Peale lived in the shadow of his father, Charles Willson Peale (Fig. 8). In the years that Dfollowed Rembrandt's death, his career and reputation contin- ued to be eclipsed by his father's more colorful and more productive life as successful artist, museum keeper, inventor, and naturalist. Just as Rembrandt's life pales in comparison to his father's, so does his art. When we contemplate the large number and variety of works in the elder Peak's oeuvre—the heroic portraits in the grand manner, sensitive half-lengths and dignified busts, charming conversation pieces, miniatures, history paintings, still lifes, landscapes, and even genre—we are awed by the man's inventiveness, originality, energy, and daring. Rembrandt's work does not affect us in the same way. We feel great respect for his technique, pleasure in some truly beau- tiful paintings, such as Rubens Peale with a Geranium (1801: National Gallery of Art), and intellectual interest in some penetrating char- acterizations, such as his William Findley (Fig. 16). We are impressed by Rembrandt's sensitive use of color and atmosphere and by his talent for clear and direct portraiture. However, except for that brief moment following his return from Paris in 1810 when he aspired to history painting, Rembrandt's work has a limited range: simple half- length or bust-size portraits devoid, for the most part, of accessories or complicated allusions. It is the narrow and somewhat repetitive nature of his canvases in comparison with the extent and variety of his father's work that has given Rembrandt the reputation of being an uninteresting artist, whose work comes to life only in the portraits of intimate friends or members of his family. -

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 American Philosophical Society 3/2002 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Charles Coleman Sellers Collection ca.1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope & content ..........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Indexing Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................10 Series I. Charles Willson Peale Portraits & Miniatures........................................................................10 -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

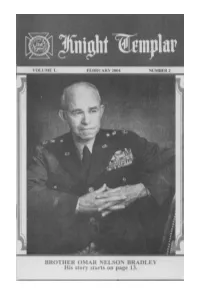

Knight Templar Magazine

Grand Master's Message for February 2004 February brings many pleasant and yet poignant memories. It is, of course, the month in which we remember those dear to us with Valentine's Day (another day of love). We are so fortunate to have those ladies in our lives who have done so much for us; our wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, etc. Speaking for the Sir Knights, we do appreciate everything that you have done for us. Many of our ladies are members of the Social Order of the Beauceant, which has raised tens of thousands of dollars, annually, for the Knights Templar Eye Foundation. Some states do not have the S.O.O.B. but do have ladies' auxiliaries, which also help their Commanderies and the Eye Foundation. Sir Knights, be sure that you recognize and thank your ladies. Some roses, candy, or whatever makes her happy would be good. She will probably wonder, what the devil you have been doing to cause you to take this action, but the net result should be good. This February is in a "Leap Year," which reminds me of a dear aunt who was born on February 29. When she passed away, she had celebrated 21 birthdays. She was my mother's next older sister and was a true workaholic. She loved to fish and would catch fish no matter what it took to catch them. Happy Birthday, Aunt Lenora! Another February memory was the tradition at our house of pruning our rose bushes on or around Valentine's Day. This was at a time when the bush was dormant and pruning would have the best effect on the bush as it came to life and began growing again in the spring. -

The Republican Theology of Benjamin Rush

THE REPUBLICAN THEOLOGY OF BENJAMIN RUSH By DONALD J. D'ELIA* A Christian [Benjamin Rush argued] cannot fail of be- ing a republican. The history of the creation of man, and of the relation of our species to each other by birth, which is recorded in the Old Testament, is the best refuta- tion that can be given to the divine right of kings, and the strongest argument that can be used in favor of the original and natural equality of all mankind. A Christian, I say again, cannot fail of being a republican, for every precept of the Gospel inculcates those degrees of humility, self-denial, and brotherly kindness, which are directly opposed to the pride of monarchy and the pageantry of a court. D)R. BENJAMIN RUSH was a revolutionary in his concep- tions of history, society, medicine, and education. He was also a revolutionary in theology. His age was one of universality, hle extrapolated boldly from politics to religion, or vice versa, with the clear warrant of the times.1 To have treated religion and politics in isolation from each other would have clashed with his analogical disposition, for which he was rightly famous. "Dr. D'Elia is associate professor of history at the State University of New York College at New Paltz. This paper was read at a session of the annual meeting of the Association at Meadville, October 9, 1965. 1Basil Willey, The Eighteenth Century Background; Studies on the Idea of Nature in the Thought of the Period (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), p. 137 et passim. -

National Historical Park Pennsylvania

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park Pennsylvania Hall was begun in the spring of 1732, when from this third casting is the one you see In May 1775, the Second Continental Con The Constitutional Convention, 1787 where Federal Hall National Memorial now ground was broken. today.) gress met in the Pennsylvania State House stands. Then, in 1790, it came to Philadel Edmund Woolley, master carpenter, and As the official bell of the Pennsylvania (Independence Hall) and decided to move The Articles of Confederation and Perpet phia for 10 years. Congress sat in the new INDEPENDENCE ual Union were drafted while the war was in Andrew Hamilton, lawyer, planned the State House, the Liberty Bell was intended to from protest to resistance. Warfare between County Court House (now known as Con building and supervised its construction. It be rung on public occasions. During the the colonists and British troops already had progress. They were agreed to by the last of gress Hall) and the United States Supreme NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK was designed in the dignity of the Georgian Revolution, when the British Army occupied begun in Massachusetts. In June the Con the Thirteen States and went into effect in Court in the new City Hall. In Congress period. Independence Hall, with its wings, Philadelphia in 1777, the bell was removed gress chose George Washington to be Gen the final year of the war. Under the Arti Hall, George Washington was inaugurated has long been considered one of the most to Allentown, where it was hidden for almost eral and Commander in Chief of the Army, cles, the Congress met in various towns, only for his second term as President.