The Green Line: an Investigation of the Arabization of the Playwriting Process Through an Exploration of Intergenerational Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

FRIDAY NIGHT in PORTLAND: KARAOKE SONG LIST Amber 311

FRIDAY NIGHT IN PORTLAND: KARAOKE SONG LIST Amber 311 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes TNT AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Somebody Kill Me Adam Sandler Lovesong Adele Rolling in the Deep Adele Rumour Has It Adele Someone like You Adele Crazy Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Hand In My Pocket Alanis Morisette You Oughta Know Alanis Morisette Ironic Alanis Morisette Black Velvet Alannah Myles Lets Stay Together Al Green Rooster Alice In Chains Would Alice In Chains Smooth Criminal Alien Ant Farm Gives You Hell All American Rejects, The You Know I'm No Good Amy Winehouse Like A Stone Audioslave Show Me How To Live Audioslave Bed Intruder Song Autotune the News January Wedding Avett Brothers Love Shack B52s Feel Like Makin Love Bad Company If I Die Young Band Perry, The Fight For Your Right To Party Beastie Boys, The Back in the USSR Beatles, The Birthday Song Beatles, The Get Back Beatles, The Helter Skelter Beatles, The Hey Jude Beatles, The I'm Only Sleeping Beatles, The Oh Darling Beatles, The Revolution #1 Beatles, The Twist And Shout Beatles, The While My Guitar Gently Weeps Beatles, The Yellow Submarine Beatles, The Staying Alive BeeGees, The Save A Horse Ride A Cowboy Big & Rich Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Use Me Up Bill Withers White Wedding Billy Idol Just A Friend Biz Markie Hard To Handle Black Crowes, The I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas, The War Pigs Black Sabbath All The Small Things Blink 182 Whats My Age Again Blink 182 One Way Or Another Blondie Tide is High Blondie Bad Touch Bloodhound Gang Song 2 (Whooo hoo) Blur 3 Little -

MUJEEBUDDIN SYED Nahi Tera Nasheman Khisr

MUJEEBUDDIN SYED Nahi tera nasheman khisr -sultani ke gumbad per Tu Shaheen hai! Basera kar pahadon ki chattanon mein "Not for you the nest on the dome of the Sultan's mansion You are the Eagle! You reside in the mountain's peaks." IQBAL W_/ALMAN RUSHDIE'S first novel, Grimus ( 1975) ,2 is marked by a characteristic heterogeneity that was to become the hallmark of later Rushdie novels. Strange and esoteric at times, Grimus has a referential sweep that assumes easy acquaintance with such diverse texts as Farid Ud 'Din Attar's The Conference of the Birds and Dante's Divina Commedia as well as an unaffected familiarity with mythologies as different as Hindu and Norse. Combining mythology and science fiction, mixing Oriental thought with Western modes, Grimus is in many ways an early manifesto of Rushdie's heterodoxical themes and innovative techniques. That Rushdie should have written this unconventional, cov• ertly subversive novel just three years after having completed his studies in Cambridge, where his area of study was, according to Khushwant Singh, "Mohammed, Islam and the Rise of the Caliphs" (1),3 is especially remarkable. The infinite number of allusions, insinuations, and puns in the novel not only reveals Rushdie's intimate knowledge of Islamic traditions and its trans• formed, hybrid, often-distorted picture that Western Orientalism spawned but also the variety of influences upon him stemming from Western literary tradition itself. At the heart of the hybrid nature of Grimus is an ingenuity that displaces what it has installed, so that the much-vaunted hybridity ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 25:4, October 1994 136 MUJEEBUDDIN SYED is itself stripped of all essentialized notions. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

' God Hath Treasuries Aneath the Throne, the Whereof

' God hath Treasuries aneath the Throne, the Keys whereof are the Tongues of the Poets.' - H a d i s i S h e r i f. HISTORY OF OTTOMAN POETRY BY E. J. W. GIBB, M. R. A.S. VOLUME I LONDON LUZAC & CO., GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1900 J V RA ^>^ (/ 'uL27 1S65 TV 0"^ TO^^t^^ 994016 PRINTED BY E. J. BRILL. LEYDEN. PREFACE. The History of Ottoman Literature has yet to be written. So far no serious work has been published, whether in Turkish or in any foreign language, that attempts to give a compre- hensive view of the whole field. Such books as have appeared up till now deal, like the present, with one side only, namely, Poetry. The reason why Ottoman prose has been thus neglected lies probably in the fact that until within the last half-century nearly all Turkish writing that was wholly or mainly literary or artistic in intention took the form of verse. Prose was as a rule reserved for practical and utilitarian purposes. Moreover, those few prose works that were artistic in aim, such as the Humayiin-Name and the later Khamsa-i Nergisi, were invariably elaborated upon the lines that at the time prevailed in poetry. Such works were of course not in metre; but this apart, their authors sought the same ends as did the poets, and sought to attain these by the same means. The merits and demerits of such writings there- fore are practically the same as those of the contemporary poetry. The History of Ottoman Poetry is thus nearly equi- valent to the History of Ottoman Literature. -

Here Without You 3 Doors Down

Links 22 Jacks - On My Way 3 Doors Down - Here without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - When I m Gone 30 Seconds to Mars - City of Angels - Intermediate 30 Seconds to Mars - Closer to the edge - 16tel und 8tel Beat 30 Seconds To Mars - From Yesterday https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpG7FzXrNSs 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings and Queens 30 Seconds To Mars - The Kill 311 - Beautiful Disaster - - Intermediate 311 - Dont Stay Home 311 - Guns - Beat ternär - Intermediate 38 Special - Hold On Loosely 4 Non Blondes - Whats Up 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 9-8tel Nine funk Play Along A Ha - Take On Me A Perfect Circle - Judith - 6-8tel 16tel Beat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgKRCXybSM A Perfect Circle - The Outsider ABBA - Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA - Mamma Mia - 8tel Beat Beginner ABBA - Super Trouper ABBA - Thank you for the music - 8tel Beat 13 ABBA - Voulez Vous Absolutum Blues - Coverdale and Page ACDC - Back in black ACDC - Big Balls ACDC - Big Gun ACDC - Black Ice ACDC - C.O.D. ACDC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC - Evil Walks ACDC - For Those About To Rock ACDC - Givin' The Dog A Bone ACDC - Go Down ACDC - Hard as a rock ACDC - Have A Drink On Me ACDC - Hells Bells https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFJFonWfBBM ACDC - Highway To Hell ACDC - I Put The Finger On You ACDC - It's A Long Way To The Top ACDC - Let's Get It Up ACDC - Money Made ACDC - Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution ACDC - Rock' n Roll Train ACDC - Shake Your Foundations ACDC - Shoot To Thrill ACDC - Shot Down in Flames ACDC - Stiff Upper Lip ACDC - The -

Song List Background Color = Songs I Can Sing

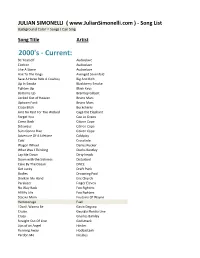

JULIAN SIMONELLI ( www.JulianSimonelli.com ) - Song List Background Color = Songs I Can Sing Song Title Artist 2000's - Current: Be Yourself Audioslave Cochise Audioslave Like A Stone Audioslave Hail To The Kings Avenged Sevenfold Save A Horse Ride A Cowboy Big And Rich Up In Smoke Blackberry Smoke Tighten Up Black Keys Bottoms Up Brantley Gilbert Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Crazy Bitch Buckcherry Aint No Rest For The Wicked Cage the Elephant Forget You Cee Lo Green Come Back Citizen Cope Sideways Citizen Cope Suns Gonna Rize Citizen Cope Advenure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cold Crossfade Wagon Wheel Darius Rucker What Was I Thinking Dierks Bentley Lay Me Down Dirty heads Down with the Sickness Disturbed Cake By The Ocean DNCE Get Lucky Draft Punk Bodies Drowning Pool Drink In My Hand Eric Church Paralyzer Finger Eleven No Way Back Foo Fighters All My Life Foo Fighters Stacies Mom Foutains Of Wayne Hemmorage Fuel I Don't Wanna Be Gavin Degraw Cruise Georgia Flordia Line Crazy Gnarles Barkley Straight Out Of Line Godsmack Lips of an Angel Hinder Running Away Hoobastank Pardon Me Incubus Wish You Were Here Incubus Dirt Road Anthem Jason Aldean Hick Town Jason Aldean She's Country Jason Aldean Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jett Cant Stop This Feeling Justin Timberlake I Want To Love Sombody Like You Keith Urban All Summer Long Kid Rock Sex On Fire Kings Of Leon Use Somebody Kings Of Leon One Step Closer Linkin Park Country Girl Luke Bryan Play It Again Luke Bryan Harder To Breathe Maroon 5 Moves Like Jager Maroon 5 One More -

Kocaer 3991.Pdf

Kocaer, Sibel (2015) The journey of an Ottoman arrior dervish : The Hı ırname (Book of Khidr) sources and reception. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20392 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. The Journey of an Ottoman Warrior Dervish: The Hızırname (Book of Khidr) Sources and Reception SIBEL KOCAER Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of the Languages and Cultures of the Near and Middle East SOAS, University of London Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

SZBA Winners Booklet En 2019 Final.Pdf

2019 LITERATURE Bensalem Himmich Morocco ‘The Self - Between Existence and Creation’ published by Le Centre Culturel Du Livre, Casablanca (2018) About the Author Bensalem Himmich is an intellectual and author, and the former Minister of Culture for Morocco. He attained his PhD in Philosophy from the University of Paris. Writing in both Arabic and French, some of his novels have been translated into several other languages. The Writers’ Union of Egypt chose Himmich’s novel Majnoun Al Hukm as one of the 100 best novels of the 20th Century, and another novel, Mu’athibati, was shortlisted for the Arab Booker International Award. Himmich has spoken at several Arab, European and American forums, and received the grand award of the French Academy of Toulouse in 2011. About the Book The Self - Between Existence and Creation is an autobiography in which Himmich offers glimpses into his life as a novelist and writer, discussing the intellectual stances he has embodied throughout his various stages of writing. Himmich’s book asserts the close connection between ‘existence’, a term impacted by philosophy, and ‘creation’, which is the path taken by oneself in struggles against various cultural and existential matters. The Self - Between Existence and Creation brings together creative dimensions fed by an author’s technical expertise and the debating nature acquired by a critical academic. The book carries a depth of knowledge and culture that commands several readings and interaction with its content. CHILDREN’S LITERATURE Hussain Almutawaa Kuwait ‘I Dream of Being a Concrete Mixer’ published by Al Hadaek Group, Beirut (2018) About the Author Hussain Almutawaa is a Kuwaiti writer and photographer born in 1989. -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

Mike's Acoustic Songlist

2 Pac California Love 3 Doors Down Here Without You Kryptonite Let Me Go Loser 30s Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree Let Me Call You Sweetheart Old Cape Cod Pistol Packin Mama Take Me Out to the Ball Game 311 All Mixed Up Amber Do You Right Flowing I'll Be Here Awhile Love Song 38 Special Caught Up in You Hold on Loosely 4 Non Blondes What's Up Adele Rolling in the Deep Set Fire to the Rain Aerosmith Living on the Edge Rag Doll Sweet Emotion What It Takes Aha Take on Me Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's 5 O'clock Somewhere Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky Alanis Morrisette You Oughta Know Alice In Chains Down Man in the Box No Excuses Nutshell Rooster Allman Bros Melissa Ramblin Man Midnight Rider America Horse with no Name Sandman Sister Golden Hair Tin Man American Authors Best Day of My Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammer Fine By Me Honey I'm Good Keep Your Head Up Andy Williams Godfather Theme Annie Lennox Here Comes the Rain Arlo Guthrie City of New Orleans Audioslave Like a Stone Avril Lavigne I'm With You Bachman Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Backstreet Boys As Long As You Love Me I Want It That Way Bad Company Ready For Love Shooting Star Badfinger No Matter What Band The Weight Baltimora Tarzan Boy Barefoot Truth Changes in the Weather Barenaked Ladies 1,000,000 Dollars Brian Wilson Call and Answer Old Apartment What a Good Boy Barry Manilow Mandy Barry White Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Beach Boys Fun, Fun, Fun Beatles Eleanor Rigby Fool on the Hill Hard Day's Night Here Comes the Sun Hey Jude Hide Your Love Away I Saw Her Standing There I Wanna Hold Your Hand I'll Follow the Sun Julia Let it Be Norweigan Wood Obladi Oblada She Came Into the Bathroom Things We Said Today Ticket to Ride We Can Work It Out When I'm Sixty-Four With a Little Help From My Friends Bee Gees Jive Talkin Islands in the Stream Massachusetts Nights on Broadway Stayin Alive To Love Somebody Tragedy Bellamy Bros. -

Jalaluddin Rumi and Hi Tasawwuf

JALALU’D-DIN RUMI AND HIS TASAWWUF JALALU’D-DIN RUMI First Edition AND HIS TASAWWUF 1985 ( Thesis approved for the Degree of Doctor of Literature in Persian of the University of Calcutta in 1960 ) Publisher : Sobbarani Paul. M. I. O. Housing Estate, Block C/2, 60/67, B. T. Road, Calcutta, India-700 002 Printer : DR. HARENDRACHANDRA PAUL, Rabindranath Da* M. A. (Triple). D. Litt.. W.B.E.S (Retired). Mudrakar Press 10/1/C, Marhatta Ditch Lane, Calcutta-700 003 Selling Agent: AYANA 73, M. G. Road, Calcutta-700 009 © Author M. I. G. HOUSING ESTATE, CALCUTTA-700 002 Ahameva svayamtdam vaddml Jus{am Derebhlruta mdnusebhlh Yarn yarn kdmaya tarn tamugram kfnoml taw Brahmanarn tamrfirn ram sumedhdm. ( fig-veda. 10/10/125 ; -It is myself who is ( always ) advising men and gods Presented to Pranab ( Pronava ) and 6ani ( Vdn\ ) ( the philosophy of Brahman ) as they desire It. I make representing Au* or Perso-Arabic Tanvin and its joyous whomsoever I choose superior to all. I make some one expression Vdg-devi ( the Goddess, Sarutaii) or Brahmd ( or Creator ), some one r*/ ( or sage ) and some Rabbu'l-'Alam ( Lord of the World ) as the Sounding- other with the Knowledge of the Self (Quoted in th eC# Self. as atha DcvisTiktam, 5 )*. Jnna Alldha yulaqqlnu'l-hlkmata •aid llsdnl al-walfint bl-qadrl himami'l-mustamVtn. —Prophet Muhammad —-Verily God teaches wisdom by the tongue of the preachers according to the aspirations of those who hear Him" (illustrated in the Mathnavi, Vol. VI, p. 170 of Husain’s edition ).