Following the Psychopath: Between Epistemological Errors and Cultural Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

FRIDAY NIGHT in PORTLAND: KARAOKE SONG LIST Amber 311

FRIDAY NIGHT IN PORTLAND: KARAOKE SONG LIST Amber 311 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes TNT AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC Somebody Kill Me Adam Sandler Lovesong Adele Rolling in the Deep Adele Rumour Has It Adele Someone like You Adele Crazy Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Hand In My Pocket Alanis Morisette You Oughta Know Alanis Morisette Ironic Alanis Morisette Black Velvet Alannah Myles Lets Stay Together Al Green Rooster Alice In Chains Would Alice In Chains Smooth Criminal Alien Ant Farm Gives You Hell All American Rejects, The You Know I'm No Good Amy Winehouse Like A Stone Audioslave Show Me How To Live Audioslave Bed Intruder Song Autotune the News January Wedding Avett Brothers Love Shack B52s Feel Like Makin Love Bad Company If I Die Young Band Perry, The Fight For Your Right To Party Beastie Boys, The Back in the USSR Beatles, The Birthday Song Beatles, The Get Back Beatles, The Helter Skelter Beatles, The Hey Jude Beatles, The I'm Only Sleeping Beatles, The Oh Darling Beatles, The Revolution #1 Beatles, The Twist And Shout Beatles, The While My Guitar Gently Weeps Beatles, The Yellow Submarine Beatles, The Staying Alive BeeGees, The Save A Horse Ride A Cowboy Big & Rich Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Use Me Up Bill Withers White Wedding Billy Idol Just A Friend Biz Markie Hard To Handle Black Crowes, The I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas, The War Pigs Black Sabbath All The Small Things Blink 182 Whats My Age Again Blink 182 One Way Or Another Blondie Tide is High Blondie Bad Touch Bloodhound Gang Song 2 (Whooo hoo) Blur 3 Little -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Here Without You 3 Doors Down

Links 22 Jacks - On My Way 3 Doors Down - Here without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - When I m Gone 30 Seconds to Mars - City of Angels - Intermediate 30 Seconds to Mars - Closer to the edge - 16tel und 8tel Beat 30 Seconds To Mars - From Yesterday https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpG7FzXrNSs 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings and Queens 30 Seconds To Mars - The Kill 311 - Beautiful Disaster - - Intermediate 311 - Dont Stay Home 311 - Guns - Beat ternär - Intermediate 38 Special - Hold On Loosely 4 Non Blondes - Whats Up 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 9-8tel Nine funk Play Along A Ha - Take On Me A Perfect Circle - Judith - 6-8tel 16tel Beat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgKRCXybSM A Perfect Circle - The Outsider ABBA - Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA - Mamma Mia - 8tel Beat Beginner ABBA - Super Trouper ABBA - Thank you for the music - 8tel Beat 13 ABBA - Voulez Vous Absolutum Blues - Coverdale and Page ACDC - Back in black ACDC - Big Balls ACDC - Big Gun ACDC - Black Ice ACDC - C.O.D. ACDC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC - Evil Walks ACDC - For Those About To Rock ACDC - Givin' The Dog A Bone ACDC - Go Down ACDC - Hard as a rock ACDC - Have A Drink On Me ACDC - Hells Bells https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFJFonWfBBM ACDC - Highway To Hell ACDC - I Put The Finger On You ACDC - It's A Long Way To The Top ACDC - Let's Get It Up ACDC - Money Made ACDC - Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution ACDC - Rock' n Roll Train ACDC - Shake Your Foundations ACDC - Shoot To Thrill ACDC - Shot Down in Flames ACDC - Stiff Upper Lip ACDC - The -

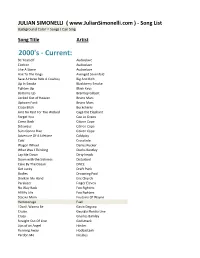

Song List Background Color = Songs I Can Sing

JULIAN SIMONELLI ( www.JulianSimonelli.com ) - Song List Background Color = Songs I Can Sing Song Title Artist 2000's - Current: Be Yourself Audioslave Cochise Audioslave Like A Stone Audioslave Hail To The Kings Avenged Sevenfold Save A Horse Ride A Cowboy Big And Rich Up In Smoke Blackberry Smoke Tighten Up Black Keys Bottoms Up Brantley Gilbert Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Crazy Bitch Buckcherry Aint No Rest For The Wicked Cage the Elephant Forget You Cee Lo Green Come Back Citizen Cope Sideways Citizen Cope Suns Gonna Rize Citizen Cope Advenure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cold Crossfade Wagon Wheel Darius Rucker What Was I Thinking Dierks Bentley Lay Me Down Dirty heads Down with the Sickness Disturbed Cake By The Ocean DNCE Get Lucky Draft Punk Bodies Drowning Pool Drink In My Hand Eric Church Paralyzer Finger Eleven No Way Back Foo Fighters All My Life Foo Fighters Stacies Mom Foutains Of Wayne Hemmorage Fuel I Don't Wanna Be Gavin Degraw Cruise Georgia Flordia Line Crazy Gnarles Barkley Straight Out Of Line Godsmack Lips of an Angel Hinder Running Away Hoobastank Pardon Me Incubus Wish You Were Here Incubus Dirt Road Anthem Jason Aldean Hick Town Jason Aldean She's Country Jason Aldean Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jett Cant Stop This Feeling Justin Timberlake I Want To Love Sombody Like You Keith Urban All Summer Long Kid Rock Sex On Fire Kings Of Leon Use Somebody Kings Of Leon One Step Closer Linkin Park Country Girl Luke Bryan Play It Again Luke Bryan Harder To Breathe Maroon 5 Moves Like Jager Maroon 5 One More -

Steve's Karaoke Songbook

Steve's Karaoke Songbook Artist Song Title Artist Song Title +44 WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS INVISIBLE MAN BEATING WAY YOU WANT ME TO, THE 10 YEARS WASTELAND A*TEENS BOUNCING OFF THE CEILING 10,000 MANIACS CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE MORE THAN THIS AALIYAH ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO, THE THESE ARE THE DAYS TRY AGAIN TROUBLE ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN 10CC THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE, THE FERNANDO 112 PEACHES & CREAM GIMME GIMME GIMME 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY DIDDY I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ME SO HORNY I HAVE A DREAM WE WANT SOME PUSSY KNOWING ME, KNOWING YOU 2 PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME MAMMA MIA 2 PAC & ERIC WILLIAMS DO FOR LOVE SOS 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN BEHIND THOSE EYES TAKE A CHANCE ON ME HERE WITHOUT YOU THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC KRYPTONITE WATERLOO LIVE FOR TODAY ABBOTT, GREGORY SHAKE YOU DOWN LOSER ABC POISON ARROW ROAD I'M ON, THE ABDUL, PAULA BLOWING KISSES IN THE WIND WHEN I'M GONE COLD HEARTED 311 ALL MIXED UP FOREVER YOUR GIRL DON'T TREAD ON ME KNOCKED OUT DOWN NEXT TO YOU LOVE SONG OPPOSITES ATTRACT 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU RUSH RUSH HOLD ON LOOSELY STATE OF ATTRACTION ROCKIN' INTO THE NIGHT STRAIGHT UP SECOND CHANCE WAY THAT YOU LOVE ME, THE TEACHER, TEACHER (IT'S JUST) WILD-EYED SOUTHERN BOYS AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 3T TEASE ME BIG BALLS 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 50 CENT AMUSEMENT PARK FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK (WE SALUTE YOU) CANDY SHOP GIRLS GOT RHYTHM DISCO INFERNO HAVE A DRINK ON ME I GET MONEY HELLS BELLS IN DA -

Mike's Acoustic Songlist

2 Pac California Love 3 Doors Down Here Without You Kryptonite Let Me Go Loser 30s Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree Let Me Call You Sweetheart Old Cape Cod Pistol Packin Mama Take Me Out to the Ball Game 311 All Mixed Up Amber Do You Right Flowing I'll Be Here Awhile Love Song 38 Special Caught Up in You Hold on Loosely 4 Non Blondes What's Up Adele Rolling in the Deep Set Fire to the Rain Aerosmith Living on the Edge Rag Doll Sweet Emotion What It Takes Aha Take on Me Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's 5 O'clock Somewhere Alan Parsons Project Eye in the Sky Alanis Morrisette You Oughta Know Alice In Chains Down Man in the Box No Excuses Nutshell Rooster Allman Bros Melissa Ramblin Man Midnight Rider America Horse with no Name Sandman Sister Golden Hair Tin Man American Authors Best Day of My Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andy Grammer Fine By Me Honey I'm Good Keep Your Head Up Andy Williams Godfather Theme Annie Lennox Here Comes the Rain Arlo Guthrie City of New Orleans Audioslave Like a Stone Avril Lavigne I'm With You Bachman Turner Overdrive Let It Ride Backstreet Boys As Long As You Love Me I Want It That Way Bad Company Ready For Love Shooting Star Badfinger No Matter What Band The Weight Baltimora Tarzan Boy Barefoot Truth Changes in the Weather Barenaked Ladies 1,000,000 Dollars Brian Wilson Call and Answer Old Apartment What a Good Boy Barry Manilow Mandy Barry White Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Beach Boys Fun, Fun, Fun Beatles Eleanor Rigby Fool on the Hill Hard Day's Night Here Comes the Sun Hey Jude Hide Your Love Away I Saw Her Standing There I Wanna Hold Your Hand I'll Follow the Sun Julia Let it Be Norweigan Wood Obladi Oblada She Came Into the Bathroom Things We Said Today Ticket to Ride We Can Work It Out When I'm Sixty-Four With a Little Help From My Friends Bee Gees Jive Talkin Islands in the Stream Massachusetts Nights on Broadway Stayin Alive To Love Somebody Tragedy Bellamy Bros. -

![The American Legion Monthly [Volume 13, No. 4 (October 1932)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6996/the-american-legion-monthly-volume-13-no-4-october-1932-3706996.webp)

The American Legion Monthly [Volume 13, No. 4 (October 1932)]

HENRY FORD - RUPERT HUGHES - PETER B. KYNE maked i/ie DIFFERENCE LEADING oil refiners add Ethyl fluid to their good gasoline to form Ethyl Gasoline. Inside the engine of your car the Ethyl fluid controls combustion. It makes gasoline de- liver more power and less harmful, wasteful heat. That is why Ethyl makes your car run at its best every minute and at the same time saves money on engine wear-and-tear. THE NEW higher Btandard of quality—adopted by every oil company that sells Ethyl Gasoline —makes it an even greater value than before. It widens still further Ethy l's margin of superiority over regular gasoline. UST as you get more enjoyment from a football game when you have good seats—so you get more pleasure and more value from your car when you use Ethyl Gasoline. Ethyl develops all FREEZING MORNINGS de- mand Ethyl's quick -starting pow- er. Ethyl is the correct winter fuel the extra performance of your motor. It doesn't call time out —the correct fuel for every season of the year because the gasoline with which Ethyl fluid is mixed is for warming up on cold mornings or overheating on long specially refined to fit the weather in which it will be used. drives. It's the all-season, all-round, all-American gasoline. GASOLINE that is to be mixed L with Ethyl must pass tests for all 1 the qualities of good gasoline. Then Ethyl fluid is added in prescribed quantity to make that gasoline de- iver its power smoothly—evenly— safely — bringing out the best per- formance of your motor. -

EDWARD LYMAN BILL EDITOR a PUBLISHER 1 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK

VOL. V. 10SINGLE CENTS COPIES 72 PAGES, INCLUDING SIDE LINE SECTION PER YEAR No. 4 ONE DOLLAR THE TALKING MACHINE WORLD EDWARD LYMAN BILL EDITOR a PUBLISHER_ 1 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK Entered as second -eau matter lifer2, I. at the poet omeeat New York,N.Y.,tinder theact of Co ogress THE TALKING MACHINE WORLD. mits .LeameardtaimiliMIMPINIMPIUMNINEP. ToI3usiness men in every line admit the value of good trade papers. Busin ess A trade paper must be origi nal-i tmust contain a Menvariety Of matter including news service-technical information-in fact it must crystallize the entire news of the special business world, and be a helpful adjunct to every department of trade. Scan the columns of The Talking Machine World closely and after you have completed an analysis of the contents of this publication see if you can duplicate its value in any othertrade! The World isa help to the talking machine business. It exerts an healthful optimism. It wields an influence for the good and every man who sells talking machines, no matter in what part of the universe he may be located, should receive this publication as regularly as it is issued.He is missing a vital business point, if he fails to do this. Thousands of dealers not only in the United States hut in every country on earth consult the pages of the World regularly. They draw from the World pleasure and profit. The talking machine business has a brilliant future, and this publication is doing much to enlarge the business horizon of every retail talking machine man in the world. -

N Sync Bye Bye Bye N Sync Crazy for You N Sync for the Girl Who Has

N Sync Bye Bye Bye N Sync Crazy For You N Sync For The Girl Who Has Everything N Sync God Must Have Spent A Little More Time On You N Sync Gone N Sync I Drive Myself Crazy N Sync I Need Love N Sync I Want You Back N Sync It's Gonna Be Me N Sync Pop N Sync Sailing N Sync Tearin' Up My Heart N Sync This I Promise You N Sync & Gloria Estefan Music Of My Heart N The Way Words Ge N.O.R.E.-NinaSky Oye Mi Canto Nails 88 Lines About 44 Women Naked Eyes Always Something There To Remind Me Nancy Sinatra Sugar Town Nancy Sinatra These Boots Are Made For Walkin' Napoleon XIV They're Coming To Take Me Away Nashville Black Roses Nashville Don't Put Dirt on my Grave Just Yet Nashville Fade Into You Nashville If I Didn't Know Better Nashville Love Like Mine Nashville Nothing In This World Will Ever Break My Heart Nashville This Town Nashville Undermine Nashville When The Right One Comes Along Nashville Love Like Mine Nat King Cole A Blossom Fell Nat King Cole Answer Me My Love Nat King Cole Darling, Je Vous Aime Beaucoup Nat King Cole For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole If I May Nat King Cole L.O.V.E Nat King Cole Looking Back Nat King Cole L-O-V-E Nat King Cole Love Is Here To Stay Nat King Cole Mona Lisa Nat King Cole Pretend Nat King Cole Ramblin' Rose Nat King Cole Send For Me Nat King Cole Somewhere Along The Way Nat King Cole Stardust Nat King Cole Straighten Up and Fly Right Nat King Cole The Very Thought Of You Nat King Cole Those Lazy Hazy Crazy Days Of Summer Nat King Cole Three Little Words Nat King Cole Too Young Nat King Cole Unforgettable -

MCW Journal of a Pandemic 2020” Is in Itself a Historical Document in Time

MCW JOURNAL OF A PANDEMIC TABLE OF CONTENTS 05 Anita Aloisio 06 Marie Bourgeois 07-08 Druce Bryan 09-10 Lyna Boushel 11-12 Angelica Bourgeault 13 Cynthia Buckley 14 Doreen Chartier 15 Sandra Cohen-Rose 16-18 Sally Cooke 19 Patricia Couture 20-21 Dolly Dastoor 22-23 Bonnie Destounis 24-27 Rena Entus 28 Sandra Heijl 29 Constance Henry 30 Donna Jensen 31-32 Brandy Jungandi 33 Joan Macklin 34 Kathryn McMorrow 35-36 Linda Monteiro 37 Alison Oxlade 38-39 Maria Peluso 40-41 Penny Rankin 42-45 Linda Serpone 46 Vivianne M. Silver 47-49 Renate Sutherland 50-52 Wanda Leah G. Trineer 53-54 Maïr Verthuy 55. Helen Wojcik FOREWORD I want to thank all MCW members who submitted a personal testimonial about the COVID-19 pandemic and what their lives became in dealing with their isolation. The “MCW Journal of a Pandemic 2020” is in itself a historical document in time. Years from now, in looking back, 2020 will signify how each woman celebrated their resilience and how they stepped into their personal power. Reading the testimonials is monumental in shifting our perspectives on the situation of a global pandemic. The power of words allows us to view ourselves as survivors of Covid-19 and is much more empowering than seeing each other as victims. Read- ing about the experiences of members provides an opportunity, a small prism, to share stories about life in real time. It reaffirms the knowledge that none of us suffered in silence. We were indeed “apart but together.” The critical truth is that the Journal reflects the creative means women used to over- come the challenges of Covid-19. -

Grindstone Song List

GrindStone Song List Artist Song Title 3 Days Grace Just Like You 3 Days Grace Pain 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Not My Time 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 311 / The Cure Love Song 7 Mary Three Cumbersome Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Living On the Edge Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Alice In Chains Man In The Box Alice In Chains Would Alice In Chains Check My Brain Alice In Chains No Excuses Alice In Chains Nutshell Ataris Boys Of Summer Audioslave Like a Stone Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Beastie Boys Fight For Your Right Billy Idol Rebel Yell Billy Joel You May Be Right Black Crowes Hard to Handle Blessed Union of Souls I Believe Blind Melon No Rain/Change Blur Song 2 Bob Segar/Metallica Turn The Page Bon Jovi Blood on Blood Bon Jovi Keep the Faith Bon Jovi Livin’ on a Prayer GrindStone Song List Artist Song Title Bon Jovi Wanted Dead or Alive Bon Jovi You Give Love a Bad Name Breaking Benjamin Breath Breaking Benjamin I Will Not Bow Breaking Benjamin So Cold Bruno Mars Grenade Buck Cherry Crazy Bitch Buck Cherry All Lit Up Buck Cherry Sorry Bush Glycerine Bush Machine Head Cage The Elephant Aint No Rest For the Wicked Cake I Will Survive Candlebox Far Behind Cat Stevens Wild World CCR Bad Moon Rising CCR Have You Even Seen the Rain Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Collective Soul Shine Counting Crowes Mr. Jones Counting Crowes ‘Round Here Cracker Low Creed Higher Creed My Own Prison Creed My Sacrifice Creed What If Creed What’s This Life For Creed With Arms Wide Open Crossfade Cold Danzig Mother Darius