U.S. Department of State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Labour Law and Development in Indonesia.Indb

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/37576 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Tjandra, Surya Title: Labour law and development in Indonesia Issue Date: 2016-02-04 3 The Reformasi: neo-liberalism, democracy, and labour law reform (1998 – 2006) Labour law plays an important role in labour reform, since it establishes the framework within which industrial relations and labour market operate. Changes in labour law may indicate the nature of change in industrial rela- tions systems in general. Such changes often occur in parallel with a nation’s transition from authoritarian rule to democracy, and tend to be accompa- nied by a shift in economic development strategies away from import-sub- stitution industrialisation to neo-liberal economic policies oriented toward exports. Indeed, these two pressures – democracy and neo-liberalism – are the ‘twin pressures’ for change that work on a country’s economic system (Cook, 1998). This chapter describes and analyses the changes in labour laws during the Reformasi era, after the fall of President Soeharto in May 1998,1 with particular attention to the enactment of the package of three new labour laws: the Manpower Law No. 13/2003, the Trade Union Law No. 21/2000, and the Industrial Relations Dispute Settlement Law No. 2/2004.2 The aim is to explain how and why such changes in labour law in Indonesia have occurred, and what have been the implications for labour. To this end, the chapter will investigate the context that structured the changes, i.e. democ- ratization and neo-liberal economic reform, as well as the contents of the package of the three new labour laws, including comparing them with pre- vious laws and analysing their impact on labour3 and the responses to these changes. -

Kata Pengantar

KATA PENGANTAR SBSI yang kembali kepada semangat dan jiwa perjuangan 25 April 1992 sewaktu deklarasi di bawah kepemimpinan Muchtar Pakpahan dan Raswan Suryana telah menyelenggarakan kongres ke V yang berlangsung di Hotel Acacia dari tanggal 31 Maret sampai dengan 3 April yang sekaligus dilanjutkan TFO. Kongres telah berhasil menyusun anggaran Dasar dan Anggaran Rumah Tangga yang disesuaikan dengan keadaan baru SBSI sebagai Unitaris sektoral juga memutuskan GBHO, beberapa resolusi kurikulum pelatihan dan prinsip-prinsip dan nilai-nilai perjuangan SBSI. Keputusan-keputusan kongres ini menuntun SBSI untuk berjuang menetapkan diri sebagai organisasi perjuangan dan juga organisasi pekerjaan. Kongres V SBSI mengambil mengambil tema sebagaimana kongres ke IV tahun 2003 yaitu “SBSI Kuat Rakyat Sejahtera”. Tema ini mendorong bahwa SBSI harus kuat agar dia bisa mencapai cita-cita nya atau kalau SBSI mau meraih cita-citanya dia harus menjadi serikat buruh yang kuat. Kalau mau menjadi SBSI yang kuat, dia harus kuat dalam lima program utamanya kosolidasi, advokasi, pendidikan dan pelatihan, tripartite, dan membangun administrasi dan kuangan organisasi yang kuat. SBSI harus terlebih dahulu membangun dirinya menjadi organisasi yang kuat agar dapat meningkatkan system welfarestate selanjutnya mensejahterakan buruh. Untuk membangun SBSI yang kuat, kami menetapkan target yang akan dicapai, yaitu agar terbentuk di seluruh Provinsi dan diseluruh Kota Kabupaten, dan mempunyai anggota minimal kembali 1,7 Juta pada tahun 2018. Sebab pada tahun 2018 SBSI akan memutuskan bagaimana hubungannya dengan perpolitikan karena nasib buruh ditentukan oleh politik. Untuk mencapai membangun SBSI yang kuat itu, kongres juga menetapkan SBSI menjadi pusat gerakan buruh yang bergerak dalam 3 (tiga) sesi yaitu gerakan Union Movement (Gerakan Serikat Buruh yang berpusat pada SBSI), Gerakan Politik yang nanti berfikir pada “Apakah ada organisasi yang mitra simbiose atau partai politik yang simbiose?” atau “SBSI kembali mempunyai partai” dan Gerakan ekonomi kerakyatan yang berpusat pada koperasi. -

Indonesia: Retail Foods

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/22/2016 GAIN Report Number: ID1638 Indonesia Retail Foods Retail Foods Update Approved By: Ali Abdi Prepared By: Fahwani Y. Rangkuti and Thom Wright Report Highlights: While traditional markets still account for the majority of retail food sales in Indonesia, modern retail holds a significant share and is growing. The burgeoning hypermarket, supermarket and minimarket sectors offer opportunities for U.S. food products. U.S. apples, table grapes, oranges, lemons, processed vegetables (french fries), processed fruits (dates, raisins, jams, nut paste), snack foods and juices enjoy a prominent position in Indonesia's retail outlets and traditional markets. Further growth and changes in consumer preferences, along with improved refrigeration and storage facilities, will also create additional opportunities for U.S. exporters. Post: Jakarta Trends and Outlook Indonesia is the 4th most populous nation in the world, with a population of approximately 261 million in 2017. Around 50 percent of the population is between the ages of 5 and 34 years. Emerging middle class consumers are well educated and have a growing interest in imported goods, particularly for consumer products such as processed foods. In 2015, GDP distribution at current market prices showed that about 26 percent of household consumption expenditures were spent on food items and 29 percent on non-food items (2015 GDP was $860 billion or IDR 11,540 trillion). The middle class population expanded to 56.7 percent of the total population (2013) from 37 percent (2004). -

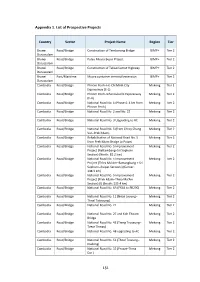

151 Appendix 1. List of Prospective Projects

Appendix 1. List of Prospective Projects Country Sector Project Name Region Tier Brunei Road/Bridge Construction of Temburong Bridge BIMP+ Tier 2 Darussalam Brunei Road/Bridge Pulau Muara Besar Project BIMP+ Tier 2 Darussalam Brunei Road/Bridge Construction of Telisai Lumut Highway BIMP+ Tier 2 Darussalam Brunei Port/Maritime Muara container terminal extension BIMP+ Tier 2 Darussalam Cambodia Road/Bridge Phnom Penh–Ho Chi Minh City Mekong Tier 1 Expressway (E-1) Cambodia Road/Bridge Phnom Penh–Sihanoukville Expressway Mekong Tier 2 (E-4) Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 1 (Phase 4: 4 km from Mekong Tier 2 Phnom Penh) Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 2 and No. 22 Mekong Tier 2 Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 3 Upgrading to AC Mekong Tier 2 Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 5 (from Chroy Chang Mekong Tier 2 Var–Prek Kdam) Cambodia Road/Bridge Rehabilitation of National Road No. 5 Mekong Tier 2 from Prek Kdam Bridge to Poipet Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 5 Improvement Mekong Tier 2 Project (Battambang–Sri Sophorn Section) (North: 81.2 km) Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 5 Improvement Mekong Tier 2 Project (Thlea Ma'Am–Battangbang + Sri Sophorn–Poipet Sections) (Center: 148.3 km) Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 5 Improvement Mekong Tier 2 Project (Prek Kdam–Thlea Ma'Am Section) (I) (South: 135.4 km) Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 6A (PK44 to PK290) Mekong Tier 2 Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. 11 (Neak Leoung– Mekong Tier 2 Thnal Toteoung) Cambodia Road/Bridge National Road No. -

Internal Conflict in Indonesia: Causes, Symptoms and Sustainable Resolution ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Parliamentary Library Research Paper No. 1 2001–02 Internal Conflict in Indonesia: Causes, Symptoms and Sustainable Resolution ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2001 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2001 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 1 2001–02 Internal Conflict in Indonesia: Causes, Symptoms and Sustainable Resolution Chris Wilson Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group 7 August 2001 Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Dr Greg Fealy, Dr Frank Frost, Derek Woolner, Dr Gary Klintworth, Andrew Chin and Doreen White for comments and assistance in the production of this paper. -

AP4-1 Detailed Comparison of Revisions (Draft) of BAPPENAS and Recommendations of PPP Study Team

AP4-1 Detailed comparison of Revisions (draft) of BAPPENAS and Recommendations of PPP Study Team Detailed comparison of Revisions (draft) of BAPPENAS and Recommendation of PPP Study Team Item Current PR No.67 Latest revision of BAPPENAS Recommendation of PPP Study Team Article 1 Article 1 Article 1 (following to be added) 1. (8)Government support is (8) Government support is a fiscal or • Contracting Agency is the Institution/State Owned General the support provided by the non-fiscal (Direct or In-direct) Enterprise/region Owned Enterprise Provision minister/head of contribution that given by the Ministry/Head of Department/ Regent • The Head of the Contracting Agency is the Agency/Head of Region to to Private Sector in form of Minister/Head of an Institution/Region/Board of Private Sector in frame of implementation of Cooperation Directors of a State Owned Enterprise/Region implementation of Agreement. * Owned Enterprise Cooperation Project based • Contracting Agency and/or the functionary of on Cooperation Agreement. (9) Government Guarantee is financial contracting agency shall be clearly separated with compensation and/or compensation in the partner of Executive Entity. other shape that given by Government/ Local Government to corporate body trough the risks share scheme in form of to fill Cooperation Agreement. * (10) State Ministry of National Development Planning /National Development Planning Agency, hereinafter mentioned as Planned Ministry, is the Ministry that has responsibility in part of National Planned Development. Article 2 (1) Minister/Head of Article 2 Agency/head of Region can cooperate with Private Sector (2) Minister/Head of Agency/Head of Region shall act as the responsible person. -

The End of Suharto

Tapol bulletin no,147, July 1998 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1998) Tapol bulletin no,147, July 1998. Tapol bulletin (147). pp. 1-28. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25993/ ISSN 1356-1154 The Indonesia Human Rights Campaign TAPOL Bulletin No. 147 July 1998 The end of Suharto 21 May 1998 will go down in world history as the day when the bloody and despotic rule ofSuharto came to an end. His 32-year rule made him Asia's longest ruler after World War IL He broke many other world records, as a mass killer and human rights violator. In 196511966 he was responsible for the slaughtt:r of at least half a million people and the incarceration of more than 1.2 million. He is also respon{iible for the deaths of 200,000 East Timorese, a third of the population, one of the worst . acts ofgenocide this century. Ignoring the blood-letting that accompanied his seizure of In the last two years, other forms of social unrest took power, the western powers fell over themselves to wel hold: assaults on local police, fury against the privileges come Suharto. He had crushed the world's largest commu nist party outside the Soviet bloc and grabbed power from From the editors: We apologise for the late arrival of President Sukarno who was seen by many in the West as a this issue. -

Indonesian Politics in Crisis

Indonesian Politics in Crisis NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES Recent and forthcoming studies of contemporary Asia Børge Bakken (ed.): Migration in China Sven Cederroth: Basket Case or Poverty Alleviation? Bangladesh Approaches the Twenty-First Century Dang Phong and Melanie Beresford: Authority Relations and Economic Decision-Making in Vietnam Mason C. Hoadley (ed.): Southeast Asian-Centred Economies or Economics? Ruth McVey (ed.): Money and Power in Provincial Thailand Cecilia Milwertz: Beijing Women Organizing for Change Elisabeth Özdalga: The Veiling Issue, Official Secularism and Popular Islam in Modern Turkey Erik Paul: Australia in Southeast Asia. Regionalisation and Democracy Ian Reader: A Poisonous Cocktail? Aum Shinrikyo’s Path to Violence Robert Thörlind: Development, Decentralization and Democracy. Exploring Social Capital and Politicization in the Bengal Region INDONESIAN POLITICS IN CRISIS The Long Fall of Suharto 1996–98 Stefan Eklöf NIAS Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Studies in Contemporary Asia series, no. 1 (series editor: Robert Cribb, University of Queensland) First published 1999 by NIAS Publishing Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) Leifsgade 33, 2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark Tel: (+45) 3254 8844 • Fax: (+45) 3296 2530 E-mail: [email protected] Online: http://nias.ku.dk/books/ Typesetting by the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Limited, Padstow, Cornwall © Stefan Eklöf 1999 British Library Catalogue in Publication Data Eklof, Stefan Indonesian politics -

Economic Crisis Spells Doom for Suharto

Tapol bulletin no, 145, February 1998 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1998) Tapol bulletin no, 145, February 1998. Tapol bulletin (145). pp. 1-24. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25995/ ISSN 1356-1154 The Indonesia Human Rights Campaign TAPOL Bulletin No. 145 February 1998 Economic crisis spells doom for Suharto Since seizing power in 1965 after one of the bloodiest massacres this century, Suharto has succeeded in staying in power for more than thirty years thanks to a system of brutal repression. Economic de velopment became the basis for the regime's claim to legitimacy, at the same time transforming the Suharto clan into one of the world's wealthiest families. But economic disaster has now brought the regime to the brink of collapse. The man who should have been crushed by the weight bled, the weight of debt denominated in dollars forced of world opinion for presiding over the massacre of up to a thousands of businesses into virtual bankruptcy, laying off million people in 1965/65, for the genocidal invasion and hundreds of thousands of people. Malaysia was also se occupation of East Timor, for the 1984 Tanjung Priok mas verely hit but the next major victim was South Korea sacre of Muslims and numerous other mass slayings and where the chaebol or conglomerates were also weighed for brutal military operations in West Papua and Aceh, will down by a mountain of debt. -

Nation-Wide Crackdown

Tapol bulletin no, 137, October 1996 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1996) Tapol bulletin no, 137, October 1996. Tapol bulletin (137). pp. 1-24. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/26004/ ISSN 1356-1154 The Indonesia Human Rights Campaign TAPOL Bulletin No. 137 October 1996 Nation-wide crackdown The Suharto regime has launched a nation-wide crackdown against the pro-democracy movement in Indonesia which is more vicious than anything since the white terror perpetrated against the Indo nesian Communist Party in the decade following the events of 1965. Hundreds have been arrested and preparations are underway for a number ofsubversion trials. The crackdown was launched in the wake of the The PRD came into being as a political party as re storming of the headquarters of the Partai Demokrasi In cently as the middle of this year. It has several affiliates, donesia, the POI, on 27 July to seize it from supporters of the PPBI which is a labour union, SMID, an organisation Megawati Sukarnoputri, chairperson of the party. Soon for students, STN which is a peasants organisation, and after the POI office was seized, the military commander of JKR, an organisation of cultural workers. Its members are Jakarta, Major-General Sutiyoso announced that his troops all very young; mostly they are students who have become were under orders to 'shoot on sight' anyone deemed to be politically active in the past year or two. -

Download Download

http://www-3.cc.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php?journal=fm&page=rt&op=printerFriendly&path[]=480&path[]=401 First Monday, Volume 1, Number 3 - 2 September 1996 By ANDREAS HARSONO Open and accessible to a global audience, the Internet represents a vehicle by which information can be disseminated quickly in comparison to newspapers and magazines. The open and democratic nature of the Internet can sometimes be at odds with policies and practices of certain governments and officials. In this article, the impact of the Internet in Indonesia is discussed, relative to a history of governmental control of the traditional media. Media Closure Go Internet Communism on the Net Appendix 1 Jakarta, July 15 - When the Indonesian Armed Forces invited around 40 newspaper editors and television executives to have a luncheon in a military building in Jakarta last June, military spokesman Brig. Gen. Amir Syarifudin asked the editors "not to exaggerate" their coverage on opposition leader Megawati Sukarnoputri. Gen. Syarifudin jokingly asked the editors not to use the words "to unseat" and "to topple" in their reporting, suggesting the editors to use the name Megawati Kiemas when referring to the chairwoman of the opposition Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI) - after the surname of her husband - rather than the name she is commonly known by - Megawati Sukarnoputri - after her father, the charismatic and revolutionary President Sukarno, whom President Suharto, the current leader, replaced after an abortive coup d'état in 1965. The general also asked the editors "to defend the dignity of the government," denying earlier media reports that the military is behind the congress held in the city of Medan, in northern Sumatra, to replace Megawati with a government-appointed leader. -

Old State and New Empire in Indonesia: Debating the Rise and Decline Of

ThirdWorld Quarterly, Vol 18, No 2, pp 321± 361, 1997 Oldstate and new empire in Indonesia:debating the rise and declineof Suharto’ s NewOrder MARK TBERGER As theMarch 1998 presidential election (which was precededby a general electionin May 1997) approaches there is everyindication that President Suhartoof Indonesia will be elected to his seventh ® ve-yearterm. There was speculationthat the long-serving former general might retire after the death of hiswife in April 1996. 1 However,in June 1996 his commitment to continue as presidentof Indonesia into the next century was apparentlyhighlighted by his government’s blatantintervention in the affairs ofthe Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI)tosuccessfully oust the party leader, Megawati Sukarnoputri. Since herelection to the top job in the PDI atthe end of 1993,Megawati (daughter of Indonesia’s ®rst president,Sukarno) had become a powerfulsymbol of demo- craticopposition. It was widelyexpected that she intendedto standfor president in1998, a postto which Suharto has previouslybeen elected unopposed by the People’s ConsultativeAssembly which meets every® veyears. Her popularity was con®rmed by the fact that her ouster precipitated one of the most violent urbanuprisings in the history of Indonesia’ s NewOrder. An armed assault by elementsof the Indonesian army on PDI headquartersin Jakarta on 27 July led toa dramaticoutpouring of opposition as Megawati’s youthfulsupporters took tothe streets. Although some observersand participants hoped that this was the beginningof a `peoplepower’ revolution similar to that which overthrew PresidentFerdinand Marcos ofthePhilippines in 1986, order was soonrestored, withthe Indonesian military taking advantage of theuprising to round up arange ofdissidents. At the same time,the cynicism and heavy-handedness of the governmenthighlighted the fact that there are cracks inthe edi® ce ofthe New Order.2 Morebroadly, although it continues to display considerable staying power,Suharto’ s NewOrder in Indonesia has beenin decline since the second halfof the1980s.