2018 Richard Menkis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

The Religious Implications of an Historical Approach to Jewish Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 214 SO 035 468 AUTHOR Furst, Rachel TITLE The Religious Implications of an Historical Approach to Jewish Studies. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 59p.; Prepared by the Academy for Torah Initiatives and Directions (Jerusalem, Israel). AVAILABLE FROM Academy for Torah Initiatives and Directions,9 HaNassi Street, Jerusalem 92188, Israel. Tel: 972-2-567-1719; Fax: 972-2-567-1723; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.atid.org/ . PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Development; Discourse Communities; *Jews; *Judaism; *Religion Studies; *Religious Factors; Research Methodology; Scholarship IDENTIFIERS Historical Methods; *Jewish Studies; *Torah ABSTRACT This project examines the religious implications of an approach to "limmudei kodesh" (primarily the study of Talmud) and "halakhah" (an integration of academic scholarship with traditional Torah study and the evaluation of the educational pros and cons of a curriculum built on such a synthesis) .In the concerted effort over the past century to develop a program of "Torah U-Madda" that synthesizes Torah and worldly pursuits, Torah scholars have endorsed the value of secular knowledge as a complimentary accoutrement to the "Talmud Torah" endeavor, but few have validated the application of secular academic tools and methodologies to Torah study or developed a model for such integrated Torah learning. The Torah scholar committed to synthesis seeks to employ historical knowledge and methodological tools in the decoding of halakhic texts as a means of contributing to the halakhic discourse. Traditional "Talmud Torah" does not address the realm of pesak halakhah, but it is nonetheless considered the highest form of religious expression. -

Operator Profile 2002 - 2003

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2002 - 2003 Operator .Insp 02-03 .OOS 02-03 OOS Rate 02-03 OpID City Region 112 LIMOUSINE INC. 2 0 0.0 28900 CENTER MORICHES 10 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 1 0 0.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 5 2 40.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 217 TRANSPORTATION INC 5 1 20.0 24555 STATEN ISLAND 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 201 30 14.9 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 57 4 7.0 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A ROYAL BUS COACH CORP. 1 1 100.0 30552 MAMARONECK 08 A & A SERVICE 17 3 17.6 05758 MT. VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 1 25.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 23 1 4.3 03339 ROCKAWAY BEACH 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 60 16 26.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 139 29 20.9 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT 4 0 0.0 05508 WATERTOWN 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 39 1 2.6 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 154 25 16.2 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 191 35 18.3 02303 OSWEGO 03 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 9 0 0.0 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 2 50.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 5 1 20.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILD'S GARDEN DAY CARE 1 0 0.0 04307 ROCHESTER 04 A CHILDS PLACE 12 7 58.3 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A&J TROUS INC. -

Reliable Certifications

unsaved:///new_page_1.htm Reliable Certifications Below are some Kashrus certifications KosherQuest recommends catagorized by country. If you have a question on a symbol not listed below, feel free to ask . Click here to download printable PDF and here to download a printable card. United States of America Alaska Alaska kosher-Chabad of Alaska Congregation Shomrei Ohr 1117 East 35th Avenue Anchorage, Ak 99508 Tel: (907) 279-1200 Fax: (907) 279-7890 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lubavitchjewishcenter.org Rabbi Yosef Greenberg Arizona Congregation Chofetz Chayim Southwest Torah Institute Rabbi Israel Becker 5150 E. Fifth St. Tuscon, AZ 85711 Cell: (520) 747-7780 Fax: (520) 745-6325 E-mail: [email protected] Arizona K 2110 East Lincoln Drive Phoenix, AZ 85016 Tel: (602) 944-2753 Cell: (602) 540-5612 Fax: (602) 749-1131 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.chabadaz.com Rabbi Zalman levertov, Kashrus Administrator Page 1 unsaved:///new_page_1.htm Chabad of Scottsdale 10215 North Scottsdale Road Scottsdale, AZ 85253 Tel: (480) 998-1410 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.chabadofscottsdale.org Rabbi Yossi Levertov, Director Certifies: The Scottsdale Cafe Deli & Market Congregation Young Israel & Chabad 2443 East Street Tuscon, AZ 85719 Tel: (520) 326-8362, 882-9422 Fax: (520) 327-3818 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.chabadoftuscon.com Rabbi Yossie Y. Shemtov Certifies: Fifth Street Kosher Deli & Market, Oy Vey Cafe California Central California Kosher (CCK) Chabad of Fresno 1227 East Shepherd Ave. Fresno, CA 93720 Tel: (559) 435-2770, 351-2222 Fax: (559) 435-0554 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.chabadfresno.com Rabbi Levy I. -

The Communal Life of the Sephardic Jews in New York City.Pdf

LOUIS M. HACKER SEPHARDIC JEWS IN NEW YORK CITY not having the slightest desire in the amend the federal acts would be to tween Sephardim and Ashkenazim Aegean. It must be apparent, then, world of becoming acquainted with have everything relating to the pre are more or less familiar; their beai-- that language difficulties stand as the police powers of either state or vention of conception stricken out of ing upon the separatism typical of insuperable obstacles in the path of a federal governments, the average the obscenity laws; another way * the life of the Oriental Jew will at common understanding between Se doctor and druggist are quite wary would be by permissive statute ex once be grasped. It is common phardim and Ashkenazim—at least, of the whole subject. The federal empting from their provisions the knowledge that the Sephardim speak of the first immigrant generations. laws, however, apply not only to the medical and public health professions Hebrew with a slightly different ac The habits of the life of the Se article or agent used in the prevent in the discharge of their duties. If cent, employ synagogue chants which phardim and their general psychology ion of conception, but also to all in the former method were adopted it may be described as Oriental in tone present other reasons for the exist formation on the subject. Such being would in effect throw the mails and rather than Germanic or Slavic, and ence of a real separatism. Coming the case, it is not possible for a doctor common carriers in interstate com have incorporated into their prayer- from the Levant as they have, the Se to obtain books dealing with the sci merce wide open to the advertisement bocks many liturgical poems unfamil phardim have brought a mode of life entific side of Birth Control, nor can and sale of spurious contraceptive in iar to the Ashkenazic ritual. -

JO1989-V22-N09.Pdf

Not ,iv.st a cheese, a traa1t1on... ~~ Haolam, the most trusted name in Cholov Yisroel Kosher Cheese. Cholov Yisroel A reputation earned through 25 years of scrupulous devotion and kashruth. With 12 delicious varieties. Haolam, a tradition you'll enjoy keeping. A!I Haolam Cheese products are under the strict Rabbinical supervision of: ~ SWITZERLAND The Rabbinate of K'hal Ada th Jeshurun Rabbi Avrohom Y. Schlesinger Washington Heights. NY Geneva, Switzerland THl'RM BRUS WORLD CHFf~~ECO lNC. 1'!-:W YORK. 1-'Y • The Thurm/Sherer Families wish Klal Yisroel n~1)n 1)J~'>'''>1£l N you can trust ... It has to be the new, improved parve Mi dal unsalted margarine r~~ In the Middle of Boro Park Are Special Families. They Are Waiting For A Miracle It hurts ... bearing a sick and helpless child. where-even among the finest families in our It hurts more ... not being able to give it the community. Many families are still waiting for proper care. the miracle of Mishkon. It hurts even more ... the turmoil suffered by Only you can make that miracle happen. the brothers and sisters. Mishkon. They are our children. Mishkon is helping not only its disabled resident Join in Mishkon's campaign to construct a children; it is rescuing the siblings, parents new facility on its campus to accommodate entire families from the upheaval caused by caring additional children. All contributions are for a handicapped child at home. tax-deductible. Dedication opportunities Retardation and debilitation strikes every- are available. Call 718-851-7100. Mishkon: They are our children. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

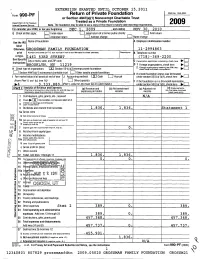

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 . -

The Sephardim of the United States: an Exploratory Study

The Sephardim of the United States: An Exploratory Study by MARC D. ANGEL WESTERN AND LEVANTINE SEPHARDIM • EARLY AMERICAN SETTLEMENT • DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN COMMUNITY • IMMIGRATION FROM LEVANT • JUDEO-SPANISH COMMUNITY • JUDEO-GREEK COMMUNITY • JUDEO-ARABIC COMMUNITY • SURVEY OF AMERICAN SEPHARDIM • BIRTHRATE • ECO- NOMIC STATUS • SECULAR AND RELIGIOUS EDUCATION • HISPANIC CHARACTER • SEPHARDI-ASHKENAZI INTERMARRIAGE • COMPARISON OF FOUR COMMUNITIES INTRODUCTION IN ITS MOST LITERAL SENSE the term Sephardi refers to Jews of Iberian origin. Sepharad is the Hebrew word for Spain. However, the term has generally come to include almost any Jew who is not Ashkenazi, who does not have a German- or Yiddish-language background.1 Although there are wide cultural divergences within the Note: It was necessary to consult many unpublished sources for this pioneering study. I am especially grateful to the Trustees of Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in New York City, for permitting me to use minutes of meetings, letters, and other unpublished materials. I am also indebted to the Synagogue's Sisterhood for making available its minutes. I wish to express my profound appreciation to Professor Nathan Goldberg of Yeshiva University for his guidance throughout every phase of this study. My special thanks go also to Messrs. Edgar J. Nathan 3rd, Joseph Papo, and Victor Tarry for reading the historical part of this essay and offering valuable suggestions and corrections, and to my wife for her excellent cooperation and assistance. Cecil Roth, "On Sephardi Jewry," Kol Sepharad, September-October 1966, pp. 2-6; Solomon Sassoon, "The Spiritual Heritage of the Sephardim," in Richard Barnett, ed., The Sephardi Heritage (New York, 1971), pp. -

Constitutional Complexity of Kosher Food Laws

The Constitutional Complexity of Kosher Food Laws * MARK POPOVSKY For nearly 100 years, many U.S. jurisdictions have had statutes in effect regulating the use of the term “kosher” in the food industry. Most kosher food laws in force today, however, should be subject to strict-scrutiny re- view and would likely be found unconstitutional. This Note argues that the government can pursue its legitimate interest in protecting kosher con- sumers from fraud by adopting a more narrowly tailored option — man- datory disclosure laws. Such laws require a vendor who claims that a product is kosher to show on what basis that claim is made. The interest- ed kosher consumer can then, upon his or her own initiative, determine whether or not the product meets the consumer’s particular religious or other needs. The state need not involve itself in deciding the theological questions inherent in determining whether a particular food is kosher. I. INTRODUCTION For nearly 100 years, many jurisdictions in the United States have had statutes in effect regulating the use of the term “kosh- er” in the food industry. Most of these laws have explicit facial preferences for “Orthodox” Jewish definitions of kosher. Even those that do not, still often require the state to select among in- ternal Jewish doctrinal disputes to define the term kosher for enforcement purposes. Only in the past twenty years have any Establishment Clause challenges successfully invalidated these laws. These challenges, however, have been limited both in scope and impact. This Note argues that most kosher food laws in force * J.D. -

Talmud Torah K'neged Kulam Towards a Culture of Life Long

Talmud Torah K'neged Kulam Towards A Culture Of Life Long Learning The wealthiest man in ancient Israel was ben Kalba Savua’a. He owned vast parcels of lands, farms, estates, and flocks, and herds of animals. Ben Kalba Savu’a had a beautiful daughter, Rachel. It was his dream that his daughter would one day marry a great scholar. With a great scholar as his son-in-law, ben Kalba Savu’a would then have everything he wanted in life. But Rachel had other ideas. Rachel fell in love with an illiterate shepherd, Akiva. She knew that something about Akiva was special. So even though her father objected, every day she would pack a picnic lunch and sneak out into the hills to meet Akiva. Rachel lay her head on Akiva’s lap. He stroked her long, beautiful hear. He gazed lovingly into her eyes and asked, “Rachel, will you marry me?” “Akiva, I will marry you, but only if you make me a promise.” “Anything! I’ll promise you anything!” Rachel stood and looked directly into Akiva’s eyes: “promise me this, Akiva: When we are blessed with a child, you will go to school with our child and learn Torah.” “But Rachel, I’m an adult! I can’t go back to school!” Akiva protested. “Akiva, do you love me?” she asked as she touched his cheek with her fingers. “Do I love you? I love you with all my heart!” he responded. “Then promise me you’ll go to school,” she demanded. “I promise.” he answered. -

Albert M. Franco Interview Transcript Accession No: 2834-001

Albert M. Franco Interview UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES w UN IVE RS ITV of WASH INGT ON Spe, i,al Col e tions Albert M. Franco Interview Transcript Accession No: 2834-001 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Guide to the Albert M. Franco. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/FrancoAlbertM2834/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search file:///C|/Users/carlsonm/Desktop/Franco/Albert%20M_%20Franco%20Interview.html[10/19/2012 3:15:49 PM] ALBERT M. FRANCO interviewed by Meta Kaplan and Adina Russak July 13, 1978 JEWISH ARCHIVES PROJECT of the Washington State Jewish Historical Society and the University Archives and Manuscripts Division University of Washington, Seattle, Washington Tape 434A Franco 1 This is an interview with attorney Albert M. Franco, on July 13, 1978 at the home of AdLna Russak. The interviewers are Meta Kaplan and Adina Russak. Q Al, where did your folks come from in the old country? A 11y parents were both born on the Island of Rhodes, which at the time of their birth was part of the t'urki•sh Empire, the Ottoman Empire. Q Were there towns on that island7 A There was the main city of Rhodes, which was the largest city of the island, and then there was the town of Lindos on the other end of The city of the Island.