Jeremy Phillip Brown on Piety and Rebellion: Essays In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism

eSharp Issue 20: New Horizons A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism Eva van Loenen (University of Southampton) Introduction In this article, I shall examine the history of Hasidic Judaism, a mystical,1 ultra-orthodox2 branch of Judaism, which values joyfully worshipping God’s presence in nature as highly as the strict observance of the laws of Torah3 and Talmud.4 In spite of being understudied, the history of Hasidic Judaism has divided historians until today. Indeed, Hasidic Jewish history is not one monolithic, clear-cut, straightforward chronicle. Rather, each scholar has created his own narrative and each one is as different as its author. While a brief introduction such as this cannot enter into all the myriad divergences and similarities between these stories, what I will attempt to do here is to incorporate and compare an array of different views in order to summarise the history of Hasidism and provide a more objective analysis, which has not yet been undertaken. Furthermore, my historical introduction in Hasidic Judaism will exemplify how mystical branches of mainstream religions might develop and shed light on an under-researched division of Judaism. The main focus of 1 Mystical movements strive for a personal experience of God or of his presence and values intuitive, spiritual insight or revelationary knowledge. The knowledge gained is generally ‘esoteric’ (‘within’ or hidden), leading to the term ‘esotericism’ as opposed to exoteric, based on the external reality which can be attested by anyone. 2 Ultra-orthodox Jews adhere most strictly to Jewish law as the holy word of God, delivered perfectly and completely to Moses on Mount Sinai. -

Chassidus on the Eh're Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) RE ’EH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah The Merit of Charity Compound forms of verbs usually indicate thoroughness. Yet when the Torah tells us (14:22), “You shall fully tithe ( aser te’aser ) all the produce of your field,” our Sages derive another concept. “ Aser bishvil shetis’asher ,” they say. “Tithe in order that you shall become wealthy.” Why is this so? When the charity a person gives, explains Rav Levi Yitzchak, comes up to Heaven, its provenance is scrutinized. Why was this particular amount giv en to charity? Then the relationship to the full amount of the harvest is discovered. There is a ration of ten to one, and the amount given is one tenth of the total. In this way the entire harvest participates in the mitzvah but only in a secondary role. Therefore, if the charity was given with a full heart, the person giving the charity merits that the quality of his donation is elevated. The following year, the entire harvest is elevated from a secondary role to a primary role in the giving of the charit y. The amount of the previous year’s harvest then becomes only one tenth of the new harvest, and the giver becomes wealthy. n Story Unfortunately, there were all too many poor people who circulated among the towns and 1 Re ’eh / [email protected] villages begging for assistance in staving off starvation. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Understanding "Unorthodox," Part 1 Satmar History and Rituals Source Sheet by Ilana Schachter

Understanding "Unorthodox," Part 1 Satmar History and Rituals Source Sheet by Ilana Schachter More info ❯ Hasidism and the Satmar Community: Background A Brief Introduction to Hasidim The Hasidim, or "pious ones" in Hebrew, belong to a special movement within Orthodox Judaism, a movement that, at its height in the first half of the nineteenth century, claimed the allegiance of millions in Eastern and Central Europe--perhaps a majority of East European Jews. Soon after its founding in the mid-eighteenth century by Jewish mystics, Hasidism rapidly gained popularity in all strata of society, especially among the less educated common people, who were drawn to its charismatic leaders and the emotional and spiritual appeal of their message, which stressed joy, faith, and ecstatic prayer, accompanied by song and dance. Like other religious revitalization movements, Hasidism was at once a call to spiritual renewal and a protest against the prevailing religious establishment and culture...After World War II, Hasidism was transplanted by immigrants to America, Israel, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe. In these most modern of places, especially in New York and other American cities, it is now thriving as an evolving creative minority that preserves the language--Yiddish--and many of the religious traditions of pre- Holocaust Eastern European Jewry. The Hasidic ideal is to live a hallowed life, in which even the most mundane action is sanctified. Hasidim live in tightly-knit communities (known as "courts") that are spiritually centered around a dynastic leader known as a rebbe, who combines political and religious authority. The many different courts and their rebbes are known by the name of the town where they originated: thus the Bobov came the town of Bobova in Poland (Galicia), the Satmar from Satu Mar in present-day Hungary, the Belz from Poland, and the Lubavitch from Russia.. -

JO1989-V22-N09.Pdf

Not ,iv.st a cheese, a traa1t1on... ~~ Haolam, the most trusted name in Cholov Yisroel Kosher Cheese. Cholov Yisroel A reputation earned through 25 years of scrupulous devotion and kashruth. With 12 delicious varieties. Haolam, a tradition you'll enjoy keeping. A!I Haolam Cheese products are under the strict Rabbinical supervision of: ~ SWITZERLAND The Rabbinate of K'hal Ada th Jeshurun Rabbi Avrohom Y. Schlesinger Washington Heights. NY Geneva, Switzerland THl'RM BRUS WORLD CHFf~~ECO lNC. 1'!-:W YORK. 1-'Y • The Thurm/Sherer Families wish Klal Yisroel n~1)n 1)J~'>'''>1£l N you can trust ... It has to be the new, improved parve Mi dal unsalted margarine r~~ In the Middle of Boro Park Are Special Families. They Are Waiting For A Miracle It hurts ... bearing a sick and helpless child. where-even among the finest families in our It hurts more ... not being able to give it the community. Many families are still waiting for proper care. the miracle of Mishkon. It hurts even more ... the turmoil suffered by Only you can make that miracle happen. the brothers and sisters. Mishkon. They are our children. Mishkon is helping not only its disabled resident Join in Mishkon's campaign to construct a children; it is rescuing the siblings, parents new facility on its campus to accommodate entire families from the upheaval caused by caring additional children. All contributions are for a handicapped child at home. tax-deductible. Dedication opportunities Retardation and debilitation strikes every- are available. Call 718-851-7100. Mishkon: They are our children. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

The Bochurim from Satmar

ב“ה The Bochurim from Satmar As told by Mrs. Leah Kahan ב“ה In the early 5740s – 1980s, a prominent Satmar many questions about the welfare of these Rosh Yeshiva and several Satmar bachurim began young bachurim, but even how their parents and learning Tanya and Chabad Chasidus and the yeshivos were faring in the wake of the attending the Rebbe’s farbrengens. All of this was controversy: done in complete secrecy, and slowly but surely, • How were the parents of the bachurim taking they became ever-more attracted to the Rebbe this change in their children? and Chasidus Chabad. After several years, they decided they wanted to stop hiding their • Are the families suffering because their children “secret,” and to become Lubavitcher on the became close to Lubavitch? outside as well. • Are the children remaining respectful to the When this became public, the Satmar community parents? Will they still be in contact? turned against these bachurim and all of • How are the yeshivos that these bachurim Lubavitch, creating much trouble to the belong to handling it? bachurim, their teachers and to Lubavitch as a whole. (In the end, everything was worked out, • How are the bachurim adjusting to this major BH). The parents of these bachurim were also change in their lives? very much against their sons learning Chabad • If they are being shunned by their community, Chasidus. how will these bachurim get married? My husband was involved with these bachurim, and I spoke with Rebbetzin about this. She had so ב“ה Respecting with Time and Money As told by Rabbi Mendel Notik One of my many jobs was to go to be extra careful.” shop at the various stores in Crown If she even thought she was going Heights. -

Shabbos Secrets - the Mysteries Revealed

Translated by Rabbi Awaharn Yaakov Finkel Shabbos Secrets - The Mysteries Revealed First Published 2003 Copyright O 2003 by Rabbi Dovid D. Meisels ISBN: 1-931681-43-0 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in an form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise, withour prior permission in writing from both the copyright holder and publisher. C<p.?< , . P*. P,' . , 8% . 3: ,. ""' * - ;., Distributed by: Isreal Book Shop -WaUvtpttrnn 501 Prospect Street w"Jw--.or@r"wn owwv Lakewood NJ 08701 Tel: (732) 901-3009 Fax: (732) 901-4012 Email: isrbkshp @ aol.com Printed in the United States of America by: Gross Brothers Printing Co., Inc. 3 125 Summit Ave., Union City N.J. 07087 This book is dedicated to be a source of merit in restoring the health and in strengthening 71 Tsn 5s 3.17 ~~w7 May Hashem send him from heaven a speedy and complete recovery of spirit and body among the other sick people of Israel. "May the Zechus of Shabbos obviate the need to cry out and may the recovery come immediately. " His parents should inerit to have much nachas from him and from the entire family. I wish to express my gratitude to Reb Avraham Yaakov Finkel, the well-known author and translator of numerous books on Torah themes, for his highly professional and meticulous translation from the Yiddish into lucid, conversational English. The original Yiddish text was published under the title Otzar Hashabbos. My special appreciation to Mrs. -

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

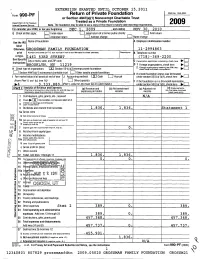

EXTENSION GRANTED UNTIL OCTOBER 15,2011 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF a or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2009 Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2009, or tax year beginning DEC 1, 200 9 , and ending NOV 30, 2010 G Check all that apply: Initial return 0 Initial return of a former public charity LJ Final return n Amended return n Address chance n Name chance of foundation A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name label Otherwise , ROSSMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION 11-2994863 print Number and street (or P O box number if mad is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ortype. 1461 53RD STREET ( 718 ) -369-2200 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exem p tion app lication is p endin g , check here 10-E] Instructions 0 1 BROOKLYN , NY 11219 Foreign organizations, check here ► 2. Foreign aanizations meeting % test, H Check type of organization. ®Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation chec here nd att ch comp t atiooe5 Section 4947(a )( nonexem pt charitable trust 0 Other taxable private foundation 1 ) E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, co! (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminatio n $ 3 , 333 , 88 0 . -

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the Freevisited Encyclopedi Ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19

Hasidic Judaism - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedi ona 1/6/2015 Page 1 of 19 Hasidic Judaism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sephardic pronunciation: [ħasiˈdut]; Ashkenazic , תודיסח :Hasidic Judaism (from the Hebrew pronunciation: [χaˈsidus]), meaning "piety" (or "loving-kindness"), is a branch of Orthodox Judaism that promotes spirituality through the popularization and internalization of Jewish mysticism as the fundamental aspect of the faith. It was founded in 18th-century Eastern Europe by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov as a reaction against overly legalistic Judaism. His example began the characteristic veneration of leadership in Hasidism as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the followers. [1] Contrary to this, Hasidic teachings cherished the sincerity and concealed holiness of the unlettered common folk, and their equality with the scholarly elite. The emphasis on the Immanent Divine presence in everything gave new value to prayer and deeds of kindness, alongside rabbinical supremacy of study, and replaced historical mystical (kabbalistic) and ethical (musar) asceticism and admonishment with Simcha, encouragement, and daily fervor.[2] Hasidism comprises part of contemporary Haredi Judaism, alongside the previous Talmudic Lithuanian-Yeshiva approach and the Sephardi and Mizrahi traditions. Its charismatic mysticism has inspired non-Orthodox Neo-Hasidic thinkers and influenced wider modern Jewish denominations, while its scholarly thought has interested contemporary academic study. Each Hasidic Jews praying in the Hasidic dynasty follows its own principles; thus, Hasidic Judaism is not one movement but a synagogue on Yom Kippur, by collection of separate groups with some commonality. There are approximately 30 larger Hasidic Maurycy Gottlieb groups, and several hundred smaller groups. Though there is no one version of Hasidism, individual Hasidic groups often share with each other underlying philosophy, worship practices, dress (borrowed from local cultures), and songs (borrowed from local cultures).