Hardware Heritage—Briefcase-Sized Computers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Portable Computing Quest

Chapter 1 The Portable Computing Quest In This Chapter ▶ Understanding portable computing ▶ Reviewing laptop history ▶ Recognizing the Tablet PC variation ▶ Getting to know the netbook ▶ Deciding whether you need a laptop figure, sometime a long time ago, one early proto-nerd had an idea. IWearing his thick glasses and a white lab coat, he stared at the large, vacuum tube monster he was tending. He wondered what it would be like to put wheels on the six-ton beast. What if they could wheel it outside and work in the sun? It was a crazy idea, yet it was the spark of a desire. Today that spark has flared into a full-blown portable computing industry. The result is the laptop, Tablet PC, or netbook computer you have in your lap, or which your lap is longing for. It’s been a long road — this chapter tells you about the journey by explaining the history of the portable computing quest. Laptop History You can’t make something portable simply by bolting a handle to it. Sure, it pleasesCOPYRIGHTED the marketing folk who understand MATERIAL that portability is a desirable trait: Put a handle on that 25-pound microwave oven and it’s suddenly “por- table.” You could put a handle on a hippopotamus and call it portable, but the thing already has legs, so what’s the point? My point is that true portability implies that a gizmo has at least these three characteristics: ✓ Lightweight ✓ No power cord ✓ Practical 005_578292-ch01.indd5_578292-ch01.indd 7 112/23/092/23/09 99:11:11 PPMM 8 Part I: The Laptop Shall Set You Free The ancient portable computer Long before people marveled over (solar pow- kids now learn to use the abacus in elementary ered) credit-card-size calculators, there existed school. -

The Canon Cat After of Release Before Macintosh

LORI EMERSON & FINN BRUNTON THE CANON CAT PROCESSING ADVANCED WORK In the fall of 2014, Finn Brunton, an assistant professor at NYU, contacted Lori Emerson, Director of the Media Archaeology Lab (MAL) at the University of Colorado, Boulder, about a rare fi nd he came across on ebay: a Canon Cat, which billed itself in 1986 as an “advanced work processor.” The MAL wasn’t immediately able to purchase the machine; however, Brunton purchased the Canon Cat with the agreement that he’d experiment with the Canon Cat for six months or so, sell it to the MAL, and then he and Emerson would co-write a piece – now, this piece – on the obscure machine from an ever-more distant past. Here, we hope to give you a glimpse into what computing could have been and still could be. 353 [SHIFT]+[DOCUMENT] [SHIFT]+[DOCUMENT] Who will the user be? The shape that early personal Jef Raskin began to work on designing the Canon Cat after computing takes rests in part on this question, with he left Apple in 1982, two years before release of Macintosh. its implicit temporal paradox. The scenario, or persona, The Cat was then introduced to the public by Canon in 1987 or model, or instance of the user threads through the for $1495 – roughly $3100 in 2015. Although the Cat was production of the machine, from input devices and discontinued after only six months, around 20,000 units performance criteria to software, industrial design, and were sold during this time. The Canon Cat fascinates me marketing. -

A Look Back at the Personal Computer's First Decade—1975 To

PROFE MS SSI E ON ST A Y L S S D A N S A S O K C R I A O thth T I W O T N E N 20 A Look Back at the Personal Computer’s First Decade—1975 to 1985 By Elizabeth M. Ferrarini IN JANUARY 1975, A POPULAR ELECTRONICS MAGAZINE COVER STORY about the $300 Altair 8800 kit by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry PC TRIVIA officially gave birth to the personal computer (PC) industry. It came ▼ Bill Gates and Paul Allen wrote the first Microsoft BASIC with two boards and slots for 16 more in the open chassis. One board for the Altair 8800. held the Intel 8080 processor chip and the other held 256 bytes. Other ▼ Steve Wozniak hand-built the first Apple from $20 worth PC kit companies included IMSAI, Cromemco, Heathkit, and of parts. In 1985, 200 Apple II's sold every five minutes. Southwest Technical Products. ▼ Initial press photo for the IBM PC showed two kids During that same year, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak created the sprawled on the living room carpet playing games. The ad 4K Apple I based on the 6502 processor chips. The two Steves added was quickly changed to one appropriate for corporate color and redesign to come up with the venerable Apple II. Equipped America. with VisiCalc, the first PC spreadsheet program, the Apple II got a lot ▼ In 1982, Time magazine's annual Man of the Year cover of people thinking about PCs as business tools. This model had a didn't go to a political figure or a celebrity, but a faceless built-in keyboard, a graphics display, and eight expansion slots. -

Retrocomputing As Preservation and Remix

Retrocomputing as Preservation and Remix Yuri Takhteyev Quinn DuPont University of Toronto University of Toronto [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper looks at the world of retrocomputing, a constellation of largely non-professional practices involving old computing technology. Retrocomputing includes many activities that can be seen as constituting “preservation.” At the same time, it is often transformative, producing assemblages that “remix” fragments from the past with newer elements or joining together historic components that were never combined before. While such “remix” may seem to undermine preservation, it allows for fragments of computing history to be reintegrated into a living, ongoing practice, contributing to preservation in a broader sense. The seemingly unorganized nature of retrocomputing assemblages also provides space for alternative “situated knowledges” and histories of computing, which can sometimes be quite sophisticated. Recognizing such alternative epistemologies paves the way for alternative approaches to preservation. Keywords: retrocomputing, software preservation, remix Recovering #popsource In late March of 2012 Jordan Mechner received a shipment from his father, a box full of old floppies. Among them was a 3.5 inch disk labelled: “Prince of Persia / Source Code (Apple) / ©1989 Jordan Mechner (Original).” Mechner’s announcement of this find on his blog the next day took the world of nerds by storm.1 Prince of Persia, a game that Mechner single-handedly developed in the late 1980s, revolutionized computer games when it came out due to its surprisingly realistic representation of human movement. After being ported to DOS and Apple’s Mac OS in the early 1990s the game sold 2 million copies (Pham, 2001). -

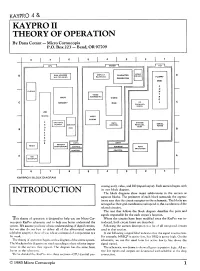

KAYPRO II THEORY of OPERATION by Dana Cotant Micro Cornucopia P.O

KAYPRO 4 & KAYPRO II THEORY OF OPERATION By Dana Cotant Micro Cornucopia P.O. Box 223 — Bend, OR 97709 CPU VIDEO VIDEO RAM ADDRESS DISPLAY CHARACTER DRIVER MULTIPLEXING BLANKING FLOPPY GENERATION DISK C 0 CLOCKS N VIDEO T ADDRESSING R MAIN VIDEO 0 OP L MEMORY RAM PARALLEL PORTS VIDEO CLOCKS DATA SYSTEM SERIAL CONTROL PARALLEL PORTS PORT DATA ADDRESS PORT SE LECTION CONTROL KAYPRO II BLOCK DIAGRAM cessing unit), video, and 1/0 (input/output). Each section begins with its own block diagram. INTRODUCTION The block diagrams show major subdivisions in the section as separate blocks. The perimeter of each block surrounds the approx- imate area that the circuit occupies on the schematic. The blocks are arranged so their grid coordinates correspond to the coordinates of the related circuitry. The text that follows the block diagram describes the parts and signals responsible for the each circuit's function. This theory of operation is designed to help you use Micro Cor- Where the circuits have been modified since the KayPro was in- nucopia's KayPro schematic and to help you better understand the troduced, both circuit forms are described. system. We assume you have a basic understanding of digital circuits, Following the section description is a list of all integrated circuits but we also do our best to define all of the abbreviated symbols used in that section. (alphabet soup) for those of you whose command of computerese is a A star following a signal label indicates that the signal is active low. bit weak. For example, MREQ* is active low, hut DRQ is active high. -

EPROM Programmer for the Kaypro

$3.00 June 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS EPROM Programmer for the Kaypro .................................. 5 Digital Plotters, A Graphic Description ................................ 8 I/O Byte: A Primer ..................................................... .1 0 Sticky Kaypros .......................................................... 12 Pascal Procedures ........................................................ 14 SBASIC Column ......................................................... 18 Kaypro Column ......................................................... 24 86 World ................................................................ 28 FOR1Hwords ........................................................... 30 Talking Serially to Your Parallel Printer ................................ 33 Introduction to Business COBOL ...................................... 34 C'ing Clearly ............................................................. 36 Parallel Printing with the Xerox 820 .................................... 41 Xerox 820, A New Double.. Density Monitor .......................... 42 On 'Your Own ........................................................... 48 Technical Tips ........................................................... 57 "THE ORIGINAL BIG BOARD" OEM - INDUSTRIAL - BUSINESS - SCIENTIFIC SINGLE BOARD COMPUTER KIT! Z-80 CPU! 64K RAM! (DO NOT CONFUSE WITH ANY OF OUR FLATTERING IMITATORSI) .,.: U) w o::J w a: Z o >Q. o (,) w w a: &L ~ Z cs: a: ;a: Q w !:: ~ :::i ~ Q THE BIG BOARD PROJECT: With thousands sold worldwide and over two years -

Hardware and Software Companies During the Microcomputer Revolution

Technology Companies Hardware and software houses of the microcomputer age James Tam Recall: Computers Before The Microprocessor James Tam Image: “A History of Computing Technology” (Williams) CPSC 409: The Microcomputer era The Microprocessor1, 2 • Intel was commissioned to design a special purpose system for a client. – Busicom (client): A Japanese hand-held calculator manufacturer – Prior to this the core money making business of Intel was manufacturing computer memory. • “Intel designed a set of four chips known as the MCS-4.”1 – The CPU for the chip was the 4004 (1971) – Also it came with ROM, RAM and a chip for I/O – It was found that by designing a general purpose computer and customizing it through software that this system could meet the client’s needs but reach a larger market. – Clock: 108 kHz3 1 http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/history/museum-story-of-intel-4004.html 2 https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-history/silicon-revolution/chip-hall-of-fame-intel-4004-microprocessor James Tam 3 http://www.intel.com/pressroom/kits/quickreffam.htm The Microprocessor1,2 (2) • Intel negotiated an arrangement with Busicom so it could freely sell these chips to others. – Busicom eventually went bankrupt! – Intel purchased the rights to the chip and marketed it on their own. James Tam CPSC 409: The Microcomputer era The Microprocessor (3) • 8080 processor: second 8 bit (data) microprocessor (first was 8008). – Clock speed: 2 MHz – Used to power the Altair computer – Many, many other processors came after this: • 80286, 80386, 80486, Pentium Series I – IV, Celeron, Core • The microprocessors development revolutionized computers by allowing computers to be more widely used. -

![John Resig and Zoo” First Video Was Uploaded Two” [April 2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0151/john-resig-and-zoo-first-video-was-uploaded-two-april-2-610151.webp)

John Resig and Zoo” First Video Was Uploaded Two” [April 2]

and parallel ports. Its 9" green which simplifies client-side monochrome screen compared HTML scripting, and has May 8th favorably to the Osborne 1’s tiny produced several other notable 5" display. JavaScript libraries, including Processing.js, Env.js, Sizzle.js, Nevertheless, the press mocked and QUnit. He was also Gary Wang its design – one magazine responsible for Khan Academy's described Kaypro as “producing [Nov 16] online environment for (Wáng Wēi) computers packaged in tin cans”. learning to program. Born: May 8, 1973; However, by mid-1983 the Fuzhou, Fujian, China company was selling more than An interest in art history led to 10,000 units a month, briefly his development of two image Wang founded the Chinese video making it the fifth-largest databases: Ukiyo-e.org which sharing company Tudou.com in computer maker in the world. collects Japanese woodblock Jan. 2005 (a month before Indeed, its rugged design made prints, and “PHAROS Images,” a YouTube [Feb 14] debuted), and it a popular choice in industry. photo archive. the site was officially launched Arthur C. Clarke [Dec 16] also Incorrect reports that he was on April 15, just over a week chose a Kaypro II to write his attacked by a vampire in 2014 before YouTube’s “Me at the 1982 novel “2010: Odyssey refer to the actor John Resig and Zoo” first video was uploaded Two” [April 2]. [April 23]. his role as the goofy town deputy, Kevin Ellis, on the TV On March 12, 2013, Wang show “True Blood”. formed “Light Chaser Animation Studios” to produce animated films targeting the Chinese market, Mother’s Day with the aim of building “The Pixar of China”. -

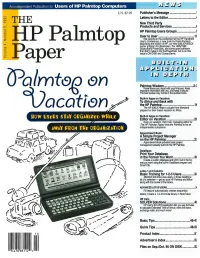

P Palmtop Aper

u.s. $7.95 Publisher's Message ................................ , Letters to the Editor .................................. ~ - E New Third Party Ln Products and Services ............................ .E ..... =Q) HP Palmtop Users Groups ...................... J E :::J User to User ............................................ 1( :z Hal reports on the excitement at the HP Handheld - P Palmtop User's Conference, a new book by David Packard "<t" describing the history of HP, our new 200LXI1000CX Q) loaner p'rogram for developers, the 1995/1996 E Subscnbers PowerDisk and some good software :::J that didn't make it into thePowerDisk, but is on this o issue's ON DISK and CompuServe. > aper PalmtoD Wisdom .................................... 2< Know ~here you stand with your finances; Keep impqrtant information with you, and keep it secure; The best quotes may not tie in the quotes books. Built·in Apps on Vacation: To Africa and Back with the HP Palmtop ....................................... 1E acafTen/ The HP 200LX lielps a couple from Maryland prepare for their dream vacation to Africa. Built·in Apps on Vacation: Editor on Vacation .................................. 2( Even on vacation, Rich Hall, managing editor for The HP Palmtop Paper, finds the Palmtop to be an indispensable companion. AP~ointment Book: ~n ~~l~epP~~'~~~~~~.~~.~~...................... 2~ Appointment Book provides basic prol'ect management already built into the HP Pa mtop. DataBase: Print Your Database in the Format You Want .......................... 3( Create a custom database and print Hout in the for mat you want using the built-in DataBase program and Smart Clip. Lotus 1·2·3 Column: Basic Training for 1-2-3 Users ............... 3~ Attention first-time Lotus users, or those needing a bH of a refresher - get out your HP Palmtop and fonow along with this review of the basics. -

The Ultimate C64 Overview Michael Steil, 25Th Chaos Communication Congress 2008

The Ultimate C64 Overview Michael Steil, http://www.pagetable.com/ 25th Chaos Communication Congress 2008 Retrocomputing is cool as never before. People play Look and Feel C64 games in emulators and listen to SID music, but few people know much about the C64 architecture A C64 only needs to be connected to power and a TV and its limitations, and what programming was like set (or monitor) to be fully functional. When turned back then. This paper attempts to give a comprehen- on, it shows a blue-on-blue theme with a startup mes- sive overview of the Commodore 64, including its in- sage and drops into a BASIC interpreter derived from ternals and quirks, making the point that classic Microsoft BASIC. In order to load and save BASIC computer systems aren't all that hard to understand - programs or use third party software, the C64 re- and that programmers today should be more aware of quires mass storage - either a “datasette” cassette the art that programming once used to be. tape drive or a disk drive like the 5.25" Commodore 1541. Commodore History Unless the user really wanted to interact with the BA- SIC interpreter, he would typically only use the BA- Commodore Business Machines was founded in 1962 SIC instructions LOAD, LIST and RUN in order to by Jack Tramiel. The company specialized on elec- access mass storage. LOAD"$",8 followed by LIST tronic calculators, and in 1976, Commodore bought shows the directory of the disk in the drive, and the chip manufacturer MOS Technology and decided LOAD"filename",8 followed by RUN would load and to have Chuck Peddle from MOS evolve their KIM-1 start a program. -

CP/M-80 Kaypro

$3.00 June-July 1985 . No. 24 TABLE OF CONTENTS C'ing Into Turbo Pascal ....................................... 4 Soldering: The First Steps. .. 36 Eight Inch Drives On The Kaypro .............................. 38 Kaypro BIOS Patch. .. 40 Alternative Power Supply For The Kaypro . .. 42 48 Lines On A BBI ........ .. 44 Adding An 8" SSSD Drive To A Morrow MD-2 ................... 50 Review: The Ztime-I .......................................... 55 BDOS Vectors (Mucking Around Inside CP1M) ................. 62 The Pascal Runoff 77 Regular Features The S-100 Bus 9 Technical Tips ........... 70 In The Public Domain... .. 13 Culture Corner. .. 76 C'ing Clearly ............ 16 The Xerox 820 Column ... 19 The Slicer Column ........ 24 Future Tense The KayproColumn ..... 33 Tidbits. .. .. 79 Pascal Procedures ........ 57 68000 Vrs. 80X86 .. ... 83 FORTH words 61 MSX In The USA . .. 84 On Your Own ........... 68 The Last Page ............ 88 NEW LOWER PRICES! NOW IN "UNKIT"* FORM TOO! "BIG BOARD II" 4 MHz Z80·A SINGLE BOARD COMPUTER WITH "SASI" HARD·DISK INTERFACE $795 ASSEMBLED & TESTED $545 "UNKIT"* $245 PC BOARD WITH 16 PARTS Jim Ferguson, the designer of the "Big Board" distributed by Digital SIZE: 8.75" X 15.5" Research Computers, has produced a stunning new computer that POWER: +5V @ 3A, +-12V @ 0.1A Cal-Tex Computers has been shipping for a year. Called "Big Board II", it has the following features: • "SASI" Interface for Winchester Disks Our "Big Board II" implements the Host portion of the "Shugart Associates Systems • 4 MHz Z80-A CPU and Peripheral Chips Interface." Adding a Winchester disk drive is no harder than attaching a floppy-disk The new Ferguson computer runs at 4 MHz. -

Getting to Know Computers

Computer Basics Getting to Know Computers Page 1 What is a Computer? A computer is an electronic device that manipulates information, or "data." It has the ability to store, retrieve, and process data. You can use a computer to type documents, send email, and browse the internet. You can also use it to handle spreadsheets, accounting, database management, presentations, games, and more. Watch the video to learn about different types of computers. Watch the video (2:39). Need help? Computers Simplified For beginning computer users, the computer aisles at an electronics store can be quite a mystery, not to mention overwhelming. However, computers really aren't that mysterious. All types of computers consist of two basic parts: Hardware is any part of your computer that has a physical structure, such as the computer monitor or keyboard. Software is any set of instructions that tells the hardware what to do. It is what guides the hardware and tells it how to accomplish each task. Some examples of software are web browsers, games, and word processors such as Microsoft Word. A motherboard (hardware) Microsoft Word (software) Anything you buy for your computer can be classified as either hardware or software. Once you learn more about these items, computers are actually very straightforward. The first electronic computer, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), was developed in ©1998-2013 Goodwill Community Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 1946. It took up 1,800 square feet and weighed 30 tons. Page 2 What are the Different Types of Computers? When most people hear the word "computer," they think of a personal computer such as a desktop or laptop computer.